In a future fight, control of advanced drones belonging to the U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force could be passed back and forth between assets from either service as the situation demands. Uncrewed platforms are set to make up the majority of the Navy’s future carrier air wings, with up to 60 percent of all aircraft on each flattop eventually being pilotless.

Navy Rear Adm. Andrew “Bucket” Loiselle provided details on the service’s advanced aviation plans, including new drones and sixth-generation crewed stealth combat jets, and cooperation with the Air Force on these efforts during a panel discussion yesterday at the Navy League’s annual Sea-Air-Space conference and exhibition. These efforts are part of the service’s broader Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program that you can learn about here. Loiselle is currently the director of the Air Warfare Division, also referred to as N98, within the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

“As we looked upon that air wing of the future, we have numerous unmanned systems,” Loiselle said. “You’ve heard talk about CCAs [and] MQ-25.”

The MQ-25 Stingray is an uncrewed tanker aircraft with a secondary intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capability that the Navy has been developing for years.

CCA stands for Collaborative Combat Aircraft and is a term that originated with the Air Force to describe future advanced drones with high degrees of autonomy intended to operate collaboratively with crewed platforms. Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall announced earlier this year that the service had begun doing future planning around a fleet of at least 1,000 CCAs, as well as 200 crewed sixth-generation stealth combat jets, all being developed as part of its own separate multi-faceted NGAD program. The CCA figure was based on a notional concept of operations that would pair two of the drones with each of the 200 NGAD combat jets and 300 stealthy F-35A Joint Strike Fighters.

However, the Air Force is still very much refining its CCA fleet structure plans, which could grow to include an even larger total number of CCAs with different types geared toward different mission sets. It’s also still figuring out how it intends to deploy and employ them. The Navy appears to be doing much the same, in increasingly close coordination with the Air Force.

“We’re developing an unmanned control station that’s already installed on three aircraft carriers, and that will be the control station for any UAS [uncrewed aerial systems] that we buy,” Rear Adm. Loiselle added. “[There is] unbelievable cooperation with the Air Force right now in the development of mission systems for both sixth-gen [combat jets] and CCAs… I’m very close to getting a signed agreement with the Air Force where we’re going to have the ability for the Navy to control Air Force CCAs and the Air Force to control Navy CCAs.”

The drone control system in question is the MD-5 Unmanned Carrier Aviation Mission Control System (UMCS), the development of which began adjacent to the Navy’s abortive Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) program. The installation of the UMCS on Navy carriers has also prompted the creation of a new Unmanned Aviation Warfare Center (UAWC) on those ships.

The Navy has previously said that the MQ-25 would be deployed first on the Nimitz class carriers USS Dwight D. Eisenhower and USS George H.W. Bush, and the latter ship has been actively used for testing that drone. It was announced last year that the plans had changed and that USS Theodore Roosevelt, another Nimitz class ship, would be the first to host the Stingray.

The expectation is that future CCAs will also be able to be controlled by various aircraft in the course of operations. The Navy has specifically said in the past that one of the core missions for its future sixth-generation crewed combat jet, also referred to as F/A-XX, will be acting as a “quarterback” for drones.

For the Navy and the Air Force, being able to readily exchange control of future drones will be key to ensuring operational flexibility. During the panel discussion yesterday, Rear Adm. Loiselle outlined a broader future naval vision where this capability could be particularly valuable.

“[The] CNO [Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Michael Gilday] was… very clear on his desire to have our future air wing be at about the 60 percent unmanned category,” Loiselle said. “So that then sets a strategic guidance for me to use in conjunction with [operations plan] execution to frame the narrative of how we’re going to develop the future naval aviation force.”

The Navy has been publicly talking about this goal for its carrier air wings to become 60 percent uncrewed since at least 2021.

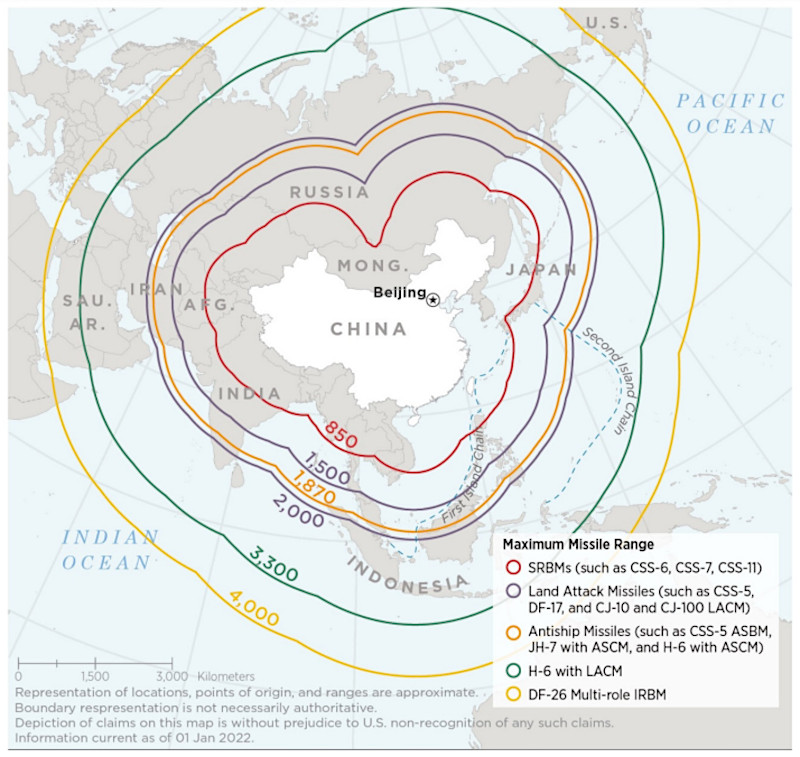

“It modifies the content of our carrier strike groups and our carrier air wings from both the content of a carrier air wing and the weapons available in the magazines. And so as you look at [operations plan] execution, you have to judge when air wing is going to come up,” he continued. “And if you’re starting from X distance away from the target, given the fact that they are considering that contested space, then the longer the range of the platform and the longer [the range] of the weapons that it carries, dictates the time at which that carrier strike group becomes effective.”

Loiselle said these realities have been driving requirements for both weapons and the platforms that will fire them, especially keeping in mind future operations across “significantly longer ranges than we have contemplated before.” He added that “there are a lot of implications in doing this.”

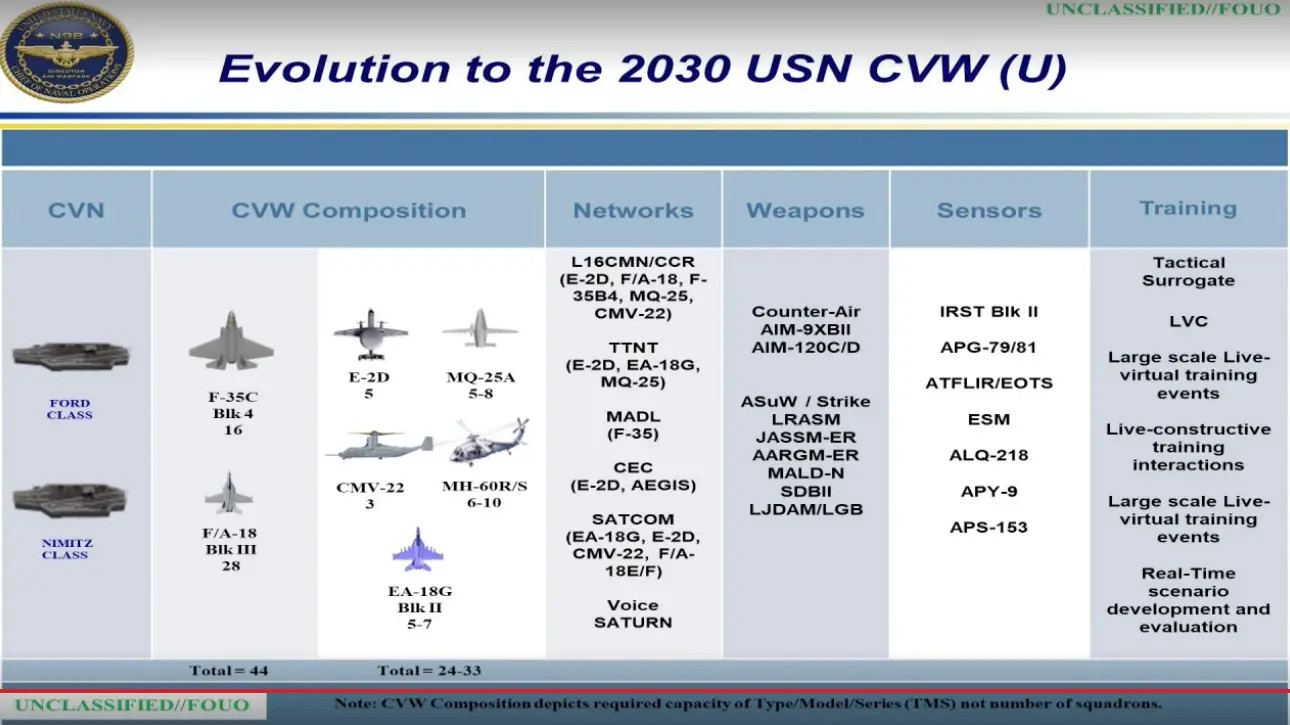

“The bottom line is when we’re building our future force that’s going to be 60 percent unmanned, then we’re going to look different than we do today. And we are no longer going to have a fighting force that has 44 strike fighters on the deck, because that’s incompatible with a 60 percent unmanned air wing,” the rear admiral explained. “So we’re going to have to change the narrative, from 44 strike fighters to how many targets can I get at what range at what time intervals, because that’s the true metric that matters.”

“The type of platform that delivers that ordnance is less important than the ability to do so,” he continued. “So we need to look at the entire portfolio that is present within the carrier strike group and how we generate that effect. Equally, we need to be cognizant of what’s available in the joint force, such that we don’t duplicate capabilities that would work within our part of that plan execution.”

“It’s about deconfliction of requirements between the entirety of DOD [the Department of Defense] such that we can generate the most effective force in the shortest period of time,” Loiselle noted. He also stressed the Navy’s position that aircraft carriers remain one of the most flexible and survivable ways to move air power quickly to wherever it is needed.

There continues to be vigorous debate about the survivability of Navy aircraft carriers in future high-end conflicts, especially a potential one against China, which is actively developing a number of weapons focused on destroying carriers over great distances. At the same time, there is no debate that large, well-established fixed bases are ever more vulnerable to similar existing and emerging enemy long-range strike capabilities. On top of that, in the Indo-Pacific region, there are simply limited numbers of suitable locations on land to operate large aerial contingents from, as well as stage other forces, to begin with.

With all this in mind, carrier strike groups, as well as potentially other naval assets, being able to readily take control of Air Force drones during operations in certain circumstances, and vice versa, could be extremely useful. A Navy carrier air wing or Air Force elements in the same region might be able to provide more on-demand escorts or other support for each other’s crewed platforms, including tactical combat jets and larger aircraft like bombers, tankers, and airlifters. Current and future Air Force assets capable of flying very long distances themselves, such as the forthcoming B-21 Raider stealth bomber, could even take control of Navy uncrewed aircraft using more localized line-of-sight links to help with their immediate missions, too.

For instance, long-range Air Force platforms like the B-21 could ‘pick up’ CCAs launched from a carrier operating far forward of any land base. They would then fly their mission into contested airspace with the help of their unmanned wingmen, then return them back to Navy control once they head back out of the high-threat area and towards the carrier’s area of operation. Unmanned tactical aircraft have a significant range advantage over their manned counterparts, which is a factor as well.

Beyond this, just being able to share fleets when in the air between the services opens up huge possibilities and operational synergies. This includes just providing CCAs in a certain area of operations that manned aircraft of both services can use while they are there and turn over to other assets once they leave. Cooperative unmanned operations between USAF and Navy CAAs without any manned aircraft present are another major plus.

In general, distributed command and control and information-sharing linkages also make it harder for an opponent to bring down an entire network by increasing the total number of nodes that would have to be struck. In this particular context, what this could mean is that any suitable Air Force or Navy control station – even ones on other aircraft, as well as on ships and at ground-based facilities – would be able to take over responsibility for drones operating in a specific area should another node go down for any reason.

It does, of course, remain to be seen how quickly the Navy will be able to implement its future naval aviation vision and transform its carrier air wings. In remarks at a separate event yesterday at the Sea-Air-Space conference, Rear Adm. Stephen Tedford, the Navy’s Program Executive Officer for Unmanned Aviation and Strike Weapons disclosed that the schedule for the MQ-25 reaching initial operational capability had slipped from 2025 to 2026 due to manufacturing issues.

Rear Adm. Loiselle also noted yesterday that for many years now funds for naval aviation modernization have often been redirected toward other priorities, including to support work on the service’s future Columbia class ballistic missile submarines. That being said, the Navy’s latest budget request for the 2024 Fiscal Year shows plans for a massive investment in F/A-XX, at least. The Navy, as well as the Air Force, have otherwise made clear that next-generation aviation capabilities are now very high on their priority lists.

Altogether, the Navy’s future combat aviation plans are continuing to coalesce, as is the Air Force’s own vision. Extensive cooperation between the two on these efforts is clearly already happening and looks set to expand even further, especially around the development and fielding of advanced drones.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com