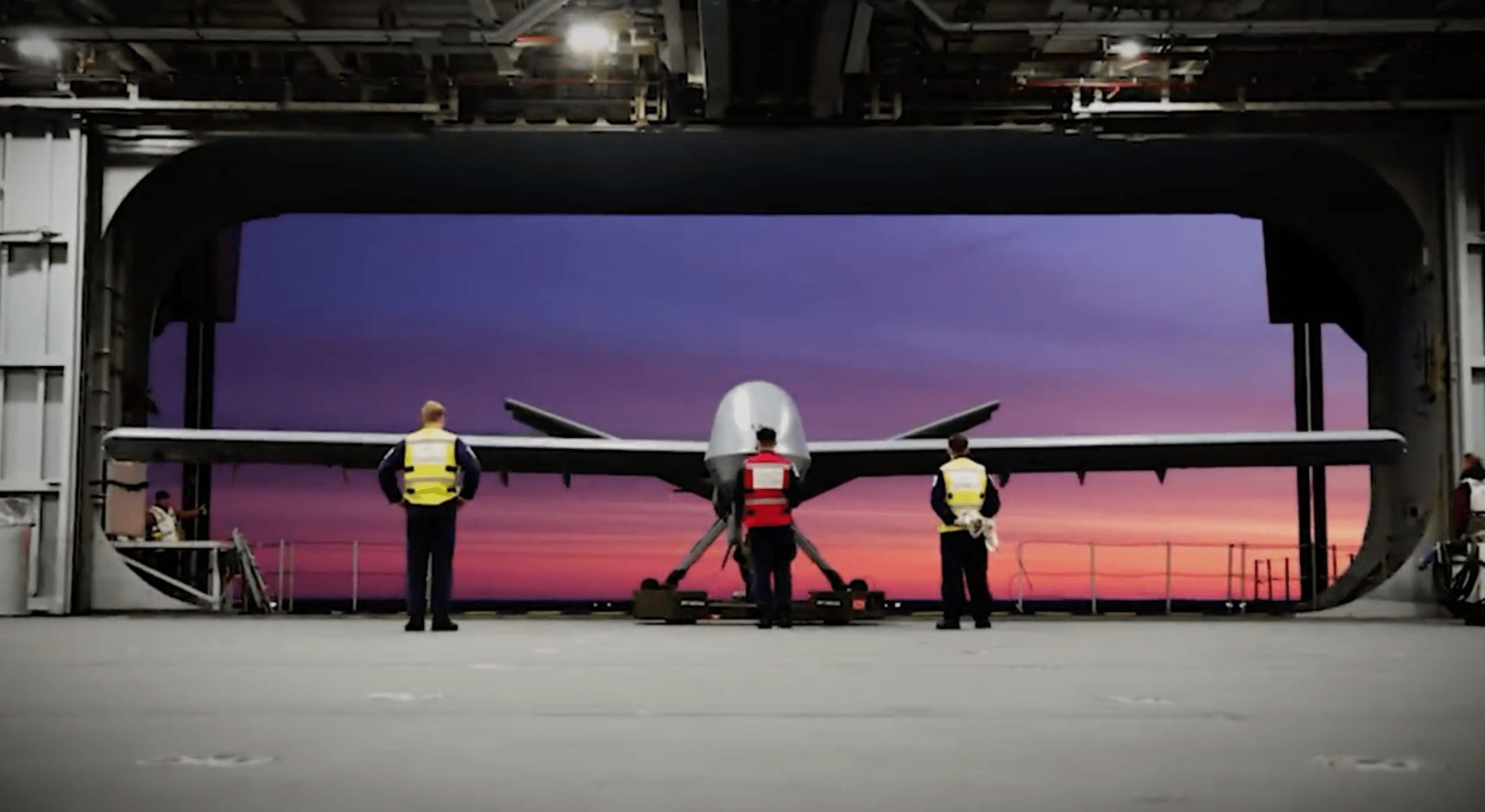

The Mojave drone, specifically developed with the ability to perform short takeoffs and landings, including from rough fields, with minimal support, has begun experimental operations aboard the U.K. Royal Navy’s aircraft carrier HMS Prince of Wales. The event marks an important milestone in the development of the Mojave — as well as the wider family of Q-1 lineage drones — which hadn’t previously operated from an aircraft carrier, as well as for the Royal Navy, which is increasingly looking to harness the capability offered by uncrewed aircraft for its carrier force.

The Mojave’s debut aboard HMS Prince of Wales took place off Virginia on the eastern coast of the United States on November 15. It came during the carrier’s fall deployment, which has been heavily focused on trials using different uncrewed aircraft. The experiments with the Mojave saw the drone both land and take off from the carrier’s 901-foot-long flight deck. HMS Prince of Wales is the Royal Navy’s biggest warship (marginally larger than its sister vessel HMS Queen Elizabeth).

Manufacturer of the Mojave, General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, Inc. (GA-ASI) described the trial as “a first-of-its-kind demonstration of its short takeoff and landing (STOL) capability on the HMS Prince of Wales.” The company added that the Mojave was controlled by an aircrew within a control station onboard the ship. “The demonstration included takeoff, circuits, and approaches and ended with a landing back onto the carrier,” GA-ASI said.

Under a $1.9-million contract, GA-ASI is using its Mojave to “demonstrate a threshold capability for a short takeoff and landing uncrewed air vehicle” aboard the HMS Prince of Wales.

“The Mojave trial is the first time that a remotely piloted air system of this size has operated to and from an aircraft carrier outside of the United States,” said Rear Admiral James Parkin, the Royal Navy’s director develop, in an official statement.

“The success of this trial heralds a new dawn in how we conduct maritime aviation and is another exciting step in the evolution of the Royal Navy’s carrier strike group into a mixed crewed and uncrewed fighting force,” Parkin added.

“With so many international partners interested in the results of these trials, I am delighted that we are taking the lead in such exciting and important work to unlock the longer-term potential of the aircraft carrier and push it deep into the 21st century as a highly potent striking capability,” said Vice Admiral Martin Connell, the Royal Navy’s Second Sea Lord.

Ahead of the latest Mojave trials, the Royal Navy had confirmed that the drone would be tested aboard the carrier. In a statement, the Royal Navy said that, by the time HMS Prince of Wales returns to the United Kingdom in December, it will have “operated advanced drone technologies, demonstrating the delivery of vital supplies without the need to use helicopters.”

Other tasks HMS Prince of Wales is assigned to complete during its fall deployment include expanding the operational envelope for the embarked F-35B Lightning stealth fighters (featuring a first night-time rolling vertical landing), as well as further experiments involving the U.S. Marine Corps MV-22B Osprey tiltrotor aircraft.

Exploring drone concepts of operations has been central, however.

Indeed, as soon as the carrier was in the English Channel, at the start of the deployment, it began trials with the W Autonomous Systems company, with a feasibility study looking at drones for the delivery of supplies to Royal Navy vessels at sea, initially flying in up to 220 pounds of stores.

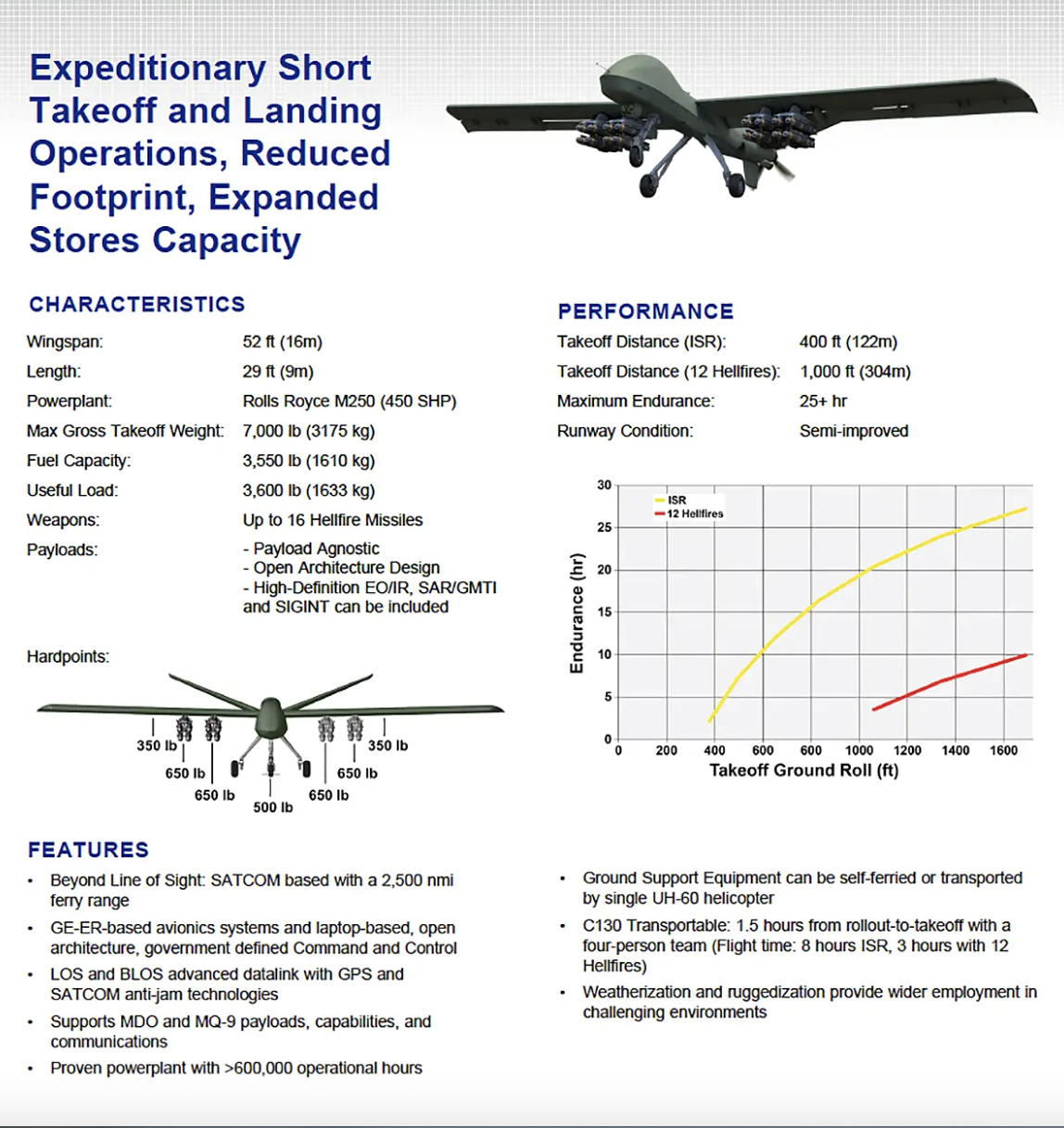

Operations with the Mojave are far more ambitious, however. The Mojave is derived from the company’s MQ-1C Gray Eagle, developed for the U.S. Army. It has a maximum takeoff weight of 3,600 pounds and is able to carry four AGM-114 Hellfire air-to-surface missiles, as part of a 1,500-pound payload. In some land-based configurations, the Mojave is able to carry as many as 16 Hellfire missiles.

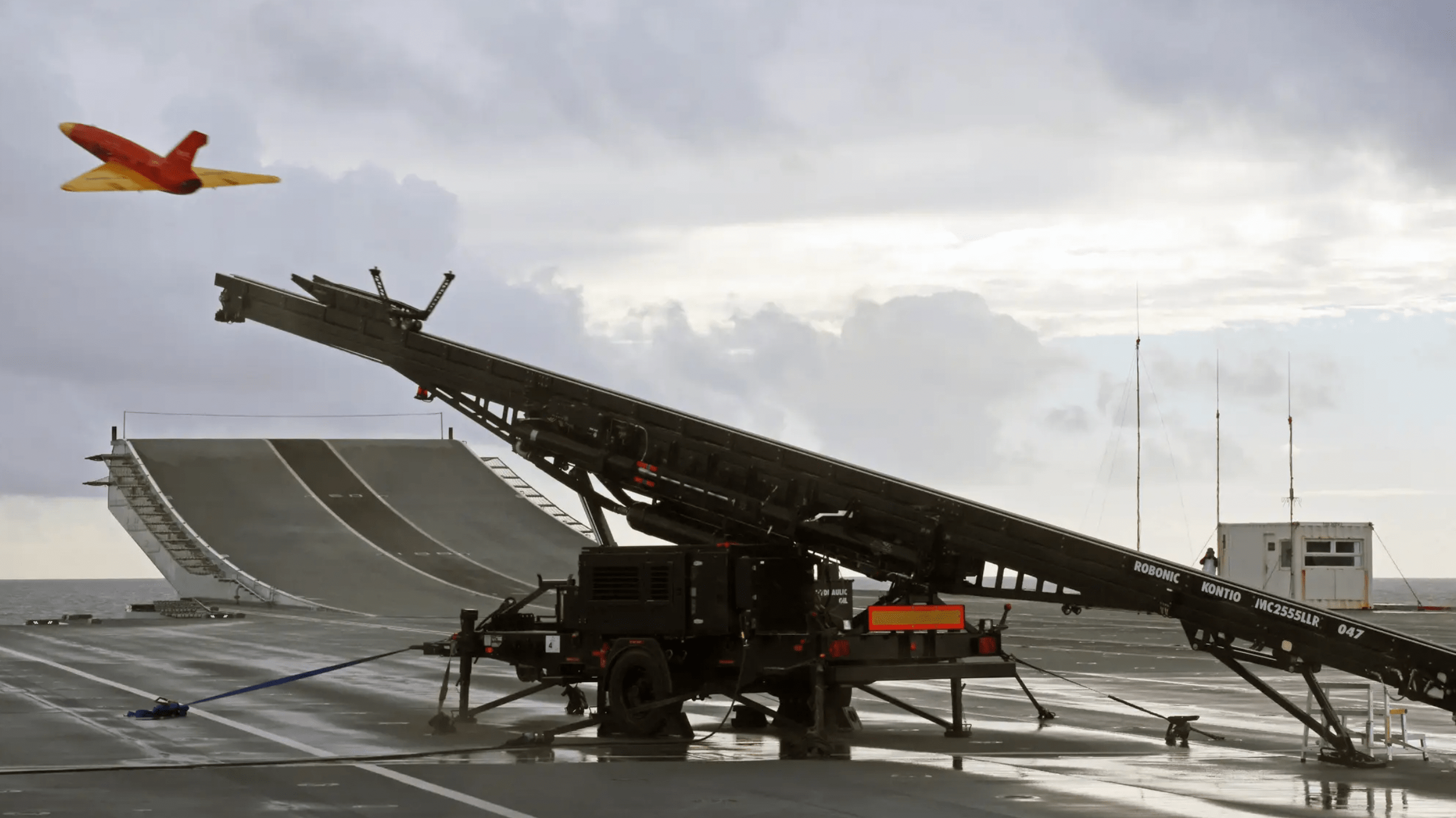

As to the specifics of operating the Mojave from the Queen Elizabeth class carrier, reports indicate that the drone took off at an angle across the deck instead of using the ‘ski jump’ takeoff ramp over the bow. GA-ASI always intended that the Mojave’s improved short-field performance and rugged landing gear would make it suitable for carrier-based operations without any need for a catapult to launch it or arresting gear during recovery. The Queen Elizabeth class carriers are currently not equipped with either catapults or arresting gear.

The drone also apparently did not operate with a full load of fuel let alone weapons, sensors, or other stores, which is common for initial tests like this. The weather conditions are also reported to have been benign. Clearly, a considerable amount of test work would still need to be undertaken if the Mojave, or a derivative of it were to be operated regularly from these warships.

In our previous coverage of the Mojave, we discussed how the drone would be likely suitable for use from aircraft carriers or large assault ships, even without launch and recovery gear:

“Mojave could have an endurance of between 10 and 12 hours when launched off a carrier-sized landing area with no weapons. This could be hugely valuable to carrier strike groups and expeditionary strike groups, providing everything from persistent armed overwatch for force protection missions in ‘brown water’ environments to airborne communications relay and surveillance functions in ‘blue water’ environments. The Marines could also use Mojave in an amphibious assault ship-based close air support and strike role. There is also the possibility of anti-submarine warfare applications, as well.”

At this stage, however, there is no formal plan for the United Kingdom to acquire the Mojave, although the platform would seem to offer some real benefits in a carrier-based context.

The drone’s long endurance would allow it to undertake a range of surveillance missions, while the ability to carry Hellfire missiles and other weapons means it could also conduct strike and critical force protection missions. Other roles could see it being used as a networking and communications relay node, as well as acting as an electronic warfare platform.

Fitted with a suitable radar, the Mojave could also act as a persistent overhead surveillance platform, filling in for the Crowsnest rotary-wing airborne early warning system that has notoriously limited endurance. This would be especially important for detecting aerial threats and sending that data to the carrier strike group for rapid exploitation.

It is notable that, as well as the STOL-capable Mojave, which would be available to the Royal Navy now, the manufacturer is also offering a wing kit for its MQ-9B Reaper, making that popular drone carrier-compatible. You can read more about the concept here. With the U.K. Royal Air Force already procuring the land-based Protector, which is an MQ-9B variant, a wing kit for a similar type of drone, for carrier operations, could be an attractive proposition.

Whether or not the United Kingdom ultimately decides to procure the Mojave or a related GA-ASI drone, the country does aspire to expand its carrier-based drone operations, if and where possible.

Earlier this year, the U.K. Royal Navy revealed details of its plans to fit its two carriers with assisted launch systems and recovery gear, enabling operations by a wider variety of fixed-wing uncrewed aircraft and, potentially, conventional takeoff and landing crewed types. This effort is known as Future Maritime Aviation Force (FMAF).

There had also been previous indications that the service wants to at least explore adding different drones to its future carrier air wing.

Providing the budget is available and the Queen Elizabeth class carriers do receive ‘cat and trap’ gear, that would open up the possibility to operate drones other than the Mojave, with that type perhaps serving simply as a proof-of-concept demonstrator before the United Kingdom moves on to more complex uncrewed naval aircraft.

“We are looking to move from STOVL [short takeoff and vertical landing] to STOL [short takeoff and landing], then to STOBAR [short takeoff but arrested recovery], and then to CATOBAR [catapult assisted takeoff but arrested recovery],” explained Colonel Phil Kelly, the Royal Navy’s Head of Carrier Strike and Maritime Aviation, about FMAF. “We are looking at a demonstrable progression that spreads out the financial cost and incrementally improves capability,” he added.

Kelly also confirmed that FMAF includes Project Ark Royal, which includes the recent Mojave tests off the U.S. East Coast. At the same time, Kelly said that while the Mojave is able to take off within 300 feet, which is easily already available with the Queen Elizabeth class, design work has been completed for modifications that would extend the carriers’ usable runway for drones to 700 feet, which would include adding sponsons to the ships.

Provided that the Mojave trials were a success, it appears that the Royal Navy’s next move will be to install some kind of recovery system to the Queen Elizabeth design, allowing operations by larger fixed-wing drones. Uncrewed aircraft in this category are an aspiration that the Royal Navy is already working toward under Project Vixen, which you can read more about here.

In summary, Project Vixen is exploring a wide variety of operational and support missions, including aerial refueling as well as strike, potentially in a loyal wingman-type role, networked together with F-35Bs. Other missions could include surveillance and electronic warfare.

Once a recovery system has been demonstrated and proven viable, the Queen Elizabeth class design would potentially then be further reworked with catapult launch gear, allowing the warships “to operate the heaviest aircraft you can imagine,” in the words of Kelly.

As well as larger, high-performance drones, the carriers could potentially also operate crewed fixed-wing aircraft that can leverage catapult and arresting gear, which would be a very significant development for the Queen Elizabeth class. Whether crewed or uncrewed, fixed-wing airborne early warning aircraft or airborne tankers would be among the platforms that these modifications could enable, bringing a step-change to offensive operations.

In 2021, the U.K. Ministry of Defense put out a request for information (RFI) for “aircraft launch and recovery equipment.” This RFI called for information on assisted launch and arrested recovery options “for a range of air vehicles, which would be suitable to fit a vessel within three to five years,” as part of the FMAF.

There have also been reports that the Royal Navy is studying different catapult launch systems, including the U.S.-developed Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS), the introduction of which has been far from trouble-free, as well as the U.K.-developed Electro Magnetic Kinetic Induction Technology demonstrator. Whether the carriers have the capacity — in terms of space and power generation — to add complex launch systems remains to be seen, however.

The challenge is actually a much larger one, should the United Kingdom follow the ‘cat and trap’ route. As well as launch and recovery systems, operations of this kind would also require new control stations, datalinks, development of procedures, and more, to ensure the drones can be safely and effectively integrated within the carrier air group.

Even before the latest trials, the Royal Navy has already begun tests with smaller, jet-powered drones launched from HMS Prince of Wales in 2021. These initial tests, which you can read more about here, involved the QinetiQ Banshee Jet 80+, best known as a target drone. This would appear to pave the way for Project Vampire, which calls for a drone in this class to perform adversary missions from the carriers, but which could later be adapted for operational missions, including cyber and electromagnetic activities (CEMA), electronic warfare (EW), and decoy purposes.

It remains to be seen just how realistic the Royal Navy’s ambitions for a future carrier-based drone fleet really are. While the feasibility of operating larger drones, in the Project Vixen category, might well prove to be overly ambitious, the recent trials with the Mojave suggest that a more modest uncrewed aircraft, even without launch and recovery gear, could also be an incredibly useful addition to the future carrier air wing.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com