Wargames that the U.S. Air Force has conducted itself and in conjunction with independent organizations continue to show the immense value offered by swarms of relatively low-cost networked drones with high degrees of autonomy. In particular, simulations have shown them to be decisive factors in the scenarios regarding the defense of the island of Taiwan against a Chinese invasion.

Last week, David Ochmanek, a senior international affairs and defense researcher at the RAND Corporation and a former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Force Development during President Barack Obama’s administration, discussed the importance of unmanned platforms in Taiwan Strait crisis-related wargaming that the think tank has done in recent years. Ochmanek offered his insight during an online chat, which you can watch in full below, hosted by the Air & Space Forces Association’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

At least some of RAND’s work in this regard has been done in cooperation with the Air Force’s Warfighting Integration Capability office, or AFWIC. Last year, the service disclosed details about a Taiwan-related wargame that AFWIC had run in 2020, which included the employment of a notional swarm of small drones, along with other unmanned platforms.

“I’m sure most everybody on this line has thought extensively about what conflict with China might look like. We think that, as force planners, we think that an invasion of Taiwan is the most appropriate scenario to use because of China’s repeatedly expressed desire to forcibly reincorporate Taiwan into the mainland if necessary and because of the severe time crunch that would be associated with defeating an invasion of Taiwan,” Ochmanek offered as an introduction to RAND’s modeling. “U.S. and allied forces may have as few as a week to 10 days to either defeat this invasion or accept the fait accompli. And the Chinese understand that if they’re to succeed in this, they either have to deter the United States from intervening or radically suppress our combat operations in the theater.”

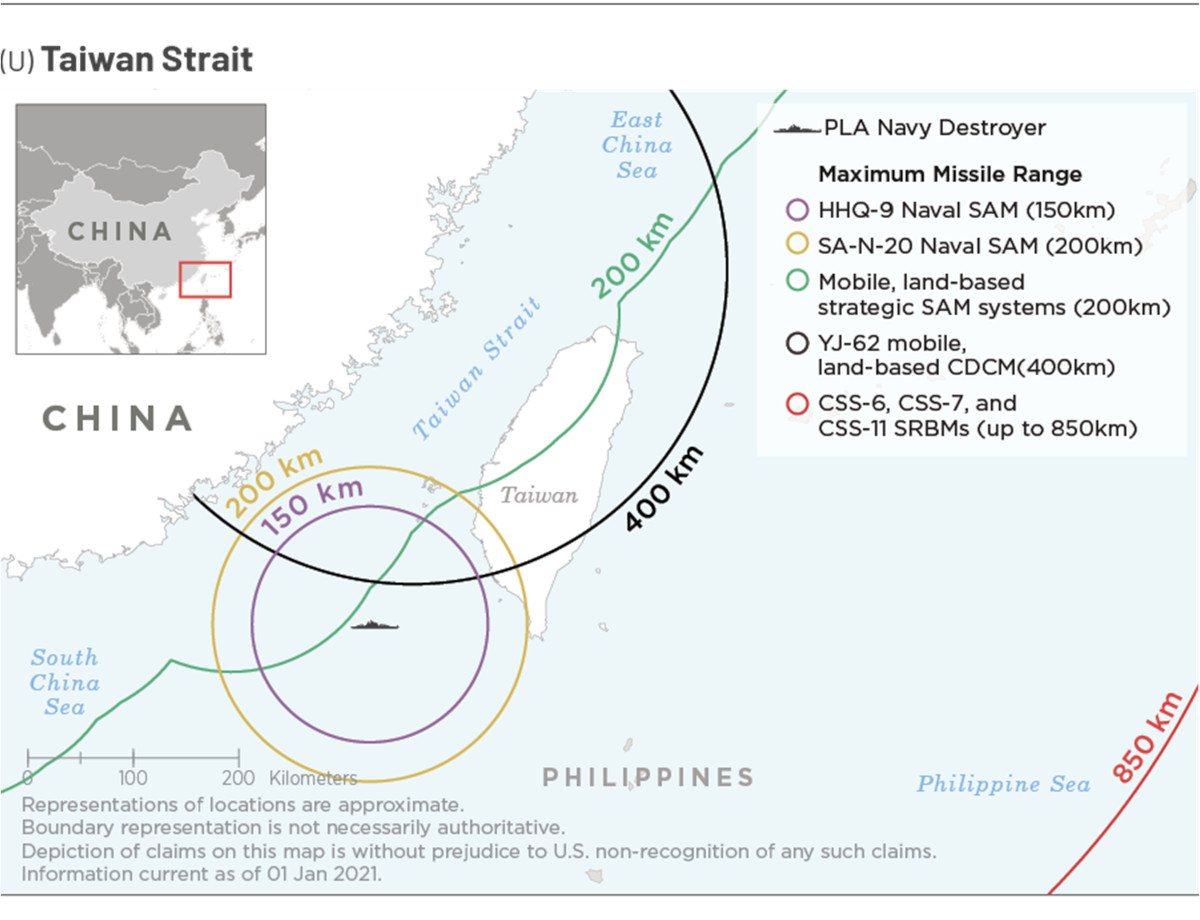

Ochmanek explained that the Chinese military has amassed a wide array of capable anti-access and area denial capabilities in the past two decades or so that would be brought to bear either to deter or engage any American forces, and their allies and partners, that might seek to respond to an invasion of Taiwan. This includes a diverse arsenal of ballistic and cruise missiles that could be used to neutralize U.S. bases across the Pacific region, anti-satellite weapons to destroy or degrade various American space-based assets, and dense integrated air defense networks bolstered by capable combat aircraft, among other things.

“With all of this, our forces are going to be confronted with the need to not just gain air superiority, which is always a priority for the commander, but to actually reach into this contested battlespace, …and find the enemy and engage the enemy’s operational center of gravity – those hundreds of ships carrying the amphibious forces across Strait, the airborne air assault aircraft carrying light infantry across the Strait,” he continued. There will be a need to “do that even in the absence of air superiority, which is a very different concept of operations from what our forces have operated with in the post-Cold War era.”

Those operational realities present immense challenges for the U.S. military in responding to a potential future Chinese invasion of Taiwan. U.S. military wargames exploring potential cross-strait crisis scenarios in recent years has more often than not, to put mildly, produced less than encouraging results when it comes to the performance of the American side.

Ochmanek says that modeling that RAND has done, including simulations conducted in cooperation with the Air Force, shows that large numbers of unmanned aircraft, especially relatively small and inexpensive designs capable of operating as fully-autonomous swarms using a distributed “mesh” data-sharing network, have shown themselves to be absolutely essential for coming out on top in these wargames.

The former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense outlined one broad, but still detailed scenario for how such a swarm of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) would be employed in the defense of Taiwan:

“We’re doing some simulations that capture scenarios in which we’re trying to rapidly sink that invasion fleet in the Strait. We’re also trying to clear the skies of PLA [People’s Liberation Army, the Chinese military] fighters, transports, and attack helos, [and] transport helos. So, think of this. Imagine 1,000 unmanned UAVs over Taiwan and over the Taiwan Strait. They are not large aircraft, but they are flying at high subsonic speed. You can imagine making their radar cross section indistinguishable from that of an F-35. And the UAVs are basically out in front. They’re doing the sensing mission. Manned aircraft are kind of hanging back. Imagine now being an SA-21 [S-400 surface to air missile system] operator on the mainland of China or on one of the surface action groups trying to project [power], your scopes are flooded with things that you gotta kill. If you don’t kill those sensors, we’re gonna find you. And if we find you, we’re gonna kill you. So, A, we’re creating defilade if you will, camouflage, for the manned aircraft to hide behind.

B, we’re potentially exhausting the enemy’s magazines of expensive SAMs, and on the right side of the cost-exchange ratio. C, you could put some jammers on a few of these UAVs, as well, to further suppress the effectiveness of the SAMs. And then, the key is, these UAVs create a sensing grid that tells you where the targets are on the surface, where the targets are in the air, so that the F-35s, F-22s can conduct their engagements passively. You never have to turn on your radar. You know what that means for survivability. So, we call these UAVs the pilot’s friend.

Now, I know there’s culturally there may be some sense of competition between manned and unmanned and so forth … from an operational perspective we do not see a downside in terms of the synergy between manned and unmanned in this model.”

What Ochmanek laid out are exactly the kinds of significant advantages an autonomous drone swarm has the potential to offer in terms of operational flexibility, as well as cost, over manned aircraft, something that The War Zone regularly highlights. Since the individual drones in an autonomous swarm are designed to collaborate with each other, this means that each individual platform does not automatically have to be configured to perform all of the desired missions that the group is collectively expected to carry out.

If a single unmanned aircraft only has to act as a sensor node, weapons truck, jammer, or datalink relay, among other things, it then also opens up the option to make that platform smaller and cheaper than it would be if it had to be a more exquisite multi-role platform. Of course, as Ochmanek himself points out, a swarm offers important additional benefits in a scenario in which it is teamed directly with manned platforms.

The video below, from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Collaborative Operations in Denied Environment (CODE) program, depicts many of drone swarm concepts that Ochmanek described.

“For many, many years this country’s been on a vector of increasingly sophisticated, expensive platforms in ever-smaller numbers, and we’ve seen the inventory of combat aircraft in the Air Force decrease because of this ineluctable trend of increasing cost per platform. That had a strong rationale when we had technical and operational superiority over our adversaries and when in fact we were very concerned about attrition,” Ochmanek said. “The advent of autonomy means that we have the opportunity now to flood the battlespace essentially with inexpensive platforms that can do the jobs that human beings have in the past done and done them actually more robustly than manned concepts.”

Ochmanek highlighted how advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI), and separate networked weapon concepts that the Air Force, among others, is working on now, will only add to a future autonomous swarm’s capabilities in any context. He indicated that this had been an additional factor in the game-changing employment of swarms in Taiwan Strait conflict simulations.

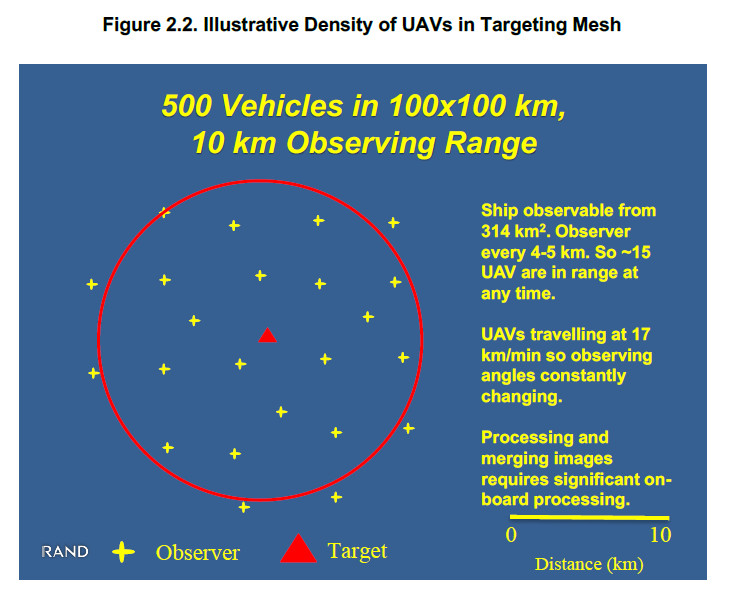

“The image we have is you send these things out to the battlespace and they are talking so to speak among themselves. When someone ‘sees’ something of interest – oh that looks like a Renhai [People’s Liberation Army Type 055 destroyer] – they’ll gang up on it, and you’ll get multiple looks … from multiple angles,” he explained. “They’ll share data. The automatic target recognition function will turn those data into a nominated target. And as weapons come in, the mesh itself will grab that weapon and say ‘your primary target is this. I’m not only going to assign you to that target, I’m going to help you hit 47 feet aft of the bow so you maximize your probability of kill against that particular platform.'”

Ochmanek acknowledged that there are concerns about the maturity of the technology needed to underpin all of this, as well as the need to mitigate various threats, especially from electronic warfare attacks. He said that RAND, at least, is confident that these challenges are surmountable, particularly through the use of a distributed ‘mesh’ network formed by the swarm itself, with systems that are available today.

“In a recent Air Force wargame, I was briefing this concept to the adjudication team, and I think it’s fair to say the adjudicators were a little bit skeptical about all the magic we were invoking for this sensing grid. And one of them asked ‘well who’s going to command and control all these hundreds of UAVs?'” Ochmanek recounted. “I said, ‘the same guy who commands and controls the 10,000 Uber drivers on the island of Manhattan.’ It’s not Mildred sitting at a switchboard saying ‘Joe, you go to the corner of 42nd and Broadway,’ no it’s the AI. It’s not that hard given the state of current computing to imagine a system where the targeting grid is quote commanding and control itself.”

At the same time, “we all know that the EMS [electromagnetic spectrum] environment in any conflict with China, or Russia for that matter, is going to be very demanding,” he added. “We also know that if you want to have literally hundreds up to thousands of UAVs operating in the battlespace it’s not going to be practical to have them all be remotely piloted, particularly when your space-based comms are under intensive attack, both lethal and nonlethal.”

“We looked at eight different classes of radios in different frequency bands, we looked at different jamming threats in terms of their proximity and intensity, and so forth in the Strait, and we concluded that in the 5G band and the high 5G band, even very intensive comm jamming can’t prevent the UAVs in the mesh from communicating, from linking with one another,” Ochmanek continued. “And we’re talking about a density in which there’s never more than 10 kilometers [just over 6 miles] between UAVs in that mesh. So that 10-kilometer link distance was our threshold value and we’re quite confident that, even with fair low power off-the-shelf radios, you can sustain that level of connectivity even in the presence of highly powerful jammers.”

The former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense further pointed out that doing initial data processing right “at the edge” of wherever the drone swarm is operating will help reduce the amount of information that needs to be transmitted to any additional node. That, in turn, reduces the total amount of bandwidth necessary – “we’re thinking one-tenth of a megabyte per second is more than sufficient” – for the network to operate effectively, further improving its resiliency.

It’s not clear exactly how much the Air Force’s own internal modeling of cross-Strait conflict might reflect the work at RAND that Ochmanek described during the recent online chat. However, as already noted, RAND has worked closely with AFWIC on wargaming out these scenarios.

The autonomous drone swarm in AFWIC’s 2020 Taiwan crisis wargame, which was linked together using a distributed mesh network, was cited as a key contributor to the defeat of Chinese forces in that particular scenario. “Although they were mostly used as a sensing grid, some were outfitted with weapons capable of — for instance — hitting small ships moving from the Chinese mainland across the strait,” according to a report on this simulation from Defense News last year.

“An unmanned vehicle that is taking off from Taiwan and doesn’t need to fly that far can actually be pretty small. And because it’s pretty small, and you’ve got one or two sensors on it, plus a communications node, then those are not expensive.,” Lt. Gen. Clint Hinote, the Air Force’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategy, Integration, and Requirements, told Defense News in a related interview. “You could buy hundreds of them.”

At the same time, the victory over the Chinese side in that Air Force simulation two years ago was described in subsequent reporting as “pyrrhic,” pointing to still-heavy losses in personnel and materiel. During the Mitchell Institute discussion, Ochmanek specifically highlighted how the U.S. military is aware of the significant existing and emerging threats to established air bases and other facilities in any future high-end conflict, especially one against China in the Pacific, potentially over Taiwan, but has not yet mitigated those risks.

“We have not solved the problem of the missile threat to airbases. Our active defenses are expensive. They’re not impermeable. They can be overwhelmed by modest sized salvos,” he said. “And yet we need to operate from inside the threat ring in order to generate the kind of combat power that is called for by these intensive operations.”

Extensive Chinese strikes against U.S. facilities across the Pacific in the opening phases of a conflict over Taiwan is a common occurrence in wargaming this scenario. Just recently, NBC News’ “Meet the Press” sponsored a series of independent Taiwan Strait wargame that was run by Washington, D.C.-based Center for a New American Security (CNAS) think tank, the outcomes of which were summarized during the show’s May 15 broadcast. The ‘red’ team, representing the regime on mainland China, was able to seize at least some Taiwanese territory in each playthrough, despite suffering significant casualties and equipment losses. It’s unclear whether a U.S. military drone swarm was factored into the CNAS-led wargaming or not.

Chinese strikes on U.S. bases, including those in Japan, as part of a Taiwan invasion operation were a key factor in these simulations. Members of the ‘blue’ team – representing the United States, Taiwan, and their allies and partners – were surprised by this aggressiveness and suggested that this was an unrealistic portrayal, with Chinese officials more likely to work up to an intervention after first making various feints and otherwise attempting to throw the international community off-balance.

However, Lt. Gen. Hinote subsequently told Air Force Magazine that this scenario “‘rhymes’ with many of the things we see in our more detailed wargaming” at “the strategic and operational levels.” He added that the airspace “is likely to be contested over Taiwan in a way we have not seen in a long time.”

During the Mitchell Institute talk, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Ochmanek said that swarms of unmanned aircraft, especially if they are runway independent, could be part of the solution to the problem of defending against or otherwise remaining resilient in the face of Chinese strikes in a defense of Taiwan scenario. He specifically cited Kratos’ XQ-58A Valkyrie unmanned aircraft, which is launched and recovered without the use of a runway, and that the Air Force is using as a testbed for various advanced warfighting experiments now, as one example. Kratos has previously presented a concept for a containerized launch system for the XQ-58A, which would further enable it to be rapidly and flexibly deployed, even to remote or austere locations.

All told, there is ever-growing evidence to support the immense and potentially game-changing value of autonomous drone swarms in any potential Taiwan Strait crisis, among other potential conflict scenarios. The U.S. government is now reportedly pushing the Taiwanese military to expand its fleets of unmanned aircraft, among other weapon systems purchases that American authorities believe would do the most to bolster the island’s ability to at least resist a Chinese invasion.

This all comes as the U.S. Intelligence Community continues to assess that the Chinese military is aiming to be in a position by 2027 where it would feel confident in its ability to succeed in any future operation to retake Taiwan by force. Of course, U.S. military officials have also said that this does not mean that the People’s Liberation Army would automatically launch such an intervention after that point.

It is worth noting that the Chinese military has been heavily investing itself in various advanced unmanned capabilities, including technology to enable networked swarms, and has arguably made more progress in fielding platforms than its American counterparts, as least as far as we know. A future conflict in and around the Taiwan Strait could very well see the People’s Liberation Army employ its own drone swarms, launched from areas on the mainland or even ships at sea.

Regardless, concerns are growing that the long-standing potential for a conflict over Taiwan could turn into a reality. It remains to be seen whether the U.S. Air Force, or any other branches of the U.S. military, will take the necessary steps to be able to deploy an autonomous drone swarm if it becomes necessary to defend the island, which looks like it could be a decisive factor in the outcome of such a crisis.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com