If you’ve seen the 2004 quirky adventure-comedy movie starring Bill Murry, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, there’s a fair chance you’ve contemplated a life at sea on your own tricked-out ex-navy vessel turned floating research and leisure ship.

Well, now’s your chance!

As it turns out, something pretty similar to the Belafonte featured in the movie is up for auction on the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) website, pictured in the top shot above and in the images below.

At the time of writing, the going bid for the ex-Navy-Coast Guard-National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) vessel now named Hi’ialakai is just $40,500 (although the reserve has not been met). The 225-foot ship – which the GSA indicates has a range of 20,000 nautical miles and is currently docked in Newport, Oregon – comes with its own onboard laboratories and a bunch of equipment for you to bring The Life Aquatic to life.

Glocks and orange crew beanies are not included in the auction lot, sadly.

Like the movie star vessel in the film, which was actually born as a Cold War Royal Navy Minesweeper, there’s more to the Hi’ialakai’s history than necessarily meets the eye. In order to trace the rich history of the vessel, we need to first look back to the 1980s, at a time when a very different kind of ocean surveillance was being undertaken.

Hi’ialakai started life as USNS Vindicator (T-AGOS-3), an ocean surveillance vessel with the U.S. Navy. Entering service in November 1984, Vindicator was the third vessel in the Stalwart class of ships – USNS Stalwart (T-AGOS-1) and Contender (T-AGOS-2) entered service with the Navy in April and June of 1984, respectively. The first 12 vessels in the 18-strong Stalwart class were built by the Tacoma Building Company based out of Tacoma, Washington state. T-AGOS-13 through T-AGOS-18 were subsequently built by Halter Marine Services in New Orleans, Louisiana.

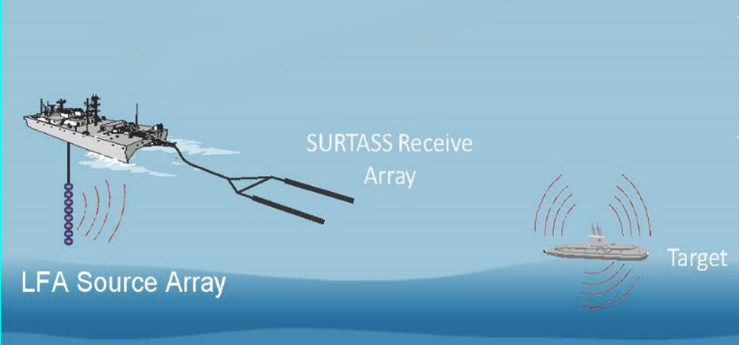

The original purpose of the early Stalwart class vessels, which were all placed in non-commissioned service with Military Sealift Command, was to monitor the movement of Soviet submarines during the Cold War. Vindicator, along with other Stalwart class vessels, used the Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System (SURTASS) to collect acoustic data in search of Soviet submarines beneath the ocean’s surface. According to the Navy, SURTASS provides “long range detection [of submarines] and cueing for tactical weapons platforms or other vessels of interest.”

As we explained in this past War Zone piece, Stalwart class vessels were fitted with the passive version of SURTASS, before a Low Frequency Active (LFA) sonar capability was introduced in the late 1980s. With the introduction of LFA sonar capability, the Navy switched to catamaran-style Victorious class vessels (T-AGOS-19 through T-AGOS-22) for its ocean surveillance ships, however, bypassing the Stalwart class vessels.

According to Ken Sayers in his book, U.S. Navy Auxiliary Vessels: A History and Directory from World War I to Today, the Stalwart class vessels, including Vindicator, used four Caterpillar D-398B diesel generators with General Electric motors. Vindicator was capable of a top speed of 11 knots, with a top speed of three knots (just under three and a half miles per hour) when towing its SURTASS array. Vindicator boasted a mixed crew of around ten Navy personnel and 19 civilians working as technicians with the vessel’s sonar equipment.

Vindicator spent less than a decade performing submarine surveillance with the Navy, however. Following the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, the Stalwart class of vessels lost much of their raison d’etre, as Sayers notes, and were subsequently retired and discarded. USNS Vindicator was stricken and then transferred to the U.S. Coast Guard in June 1993.

From June to October 1993, crew members of USCGC Tamaroa (WMEC-166) manned Vindicator during the vessel’s Coast Guard acceptance trials. In May 1994, Vindicator was accepted by the Coast Guard as USCGC Vindicator (WMEC-3) for use in counternarcotics operations, with the vessel based at Norfolk, Virginia.

In June 1994, for example, USCGC Vindicator was used in support of Operation Able Manner. The operation, which began under Presidential orders in January 1994, saw Navy and Coast Guard vessels deployed to the Windward Passage – the body of water between Haiti and Cuba – in order to interdict would-be Haitian migrants venturing to the U.S. in overloaded sailboats. Some 15,955 migrants were picked-up during the month of July 1994, as the Department of Defense indicates. According to transcripts of Senate hearings for the Department of Transportation from April 1994, USCGC Vindicator was sent to the Windward Passage in order to serve as a “repatriation ferry to transport migrants from the Migrant Processing Center (MPC) to a Haitian port of repatriation.”

Shortly after this, however, USCGC Vindicator was decommissioned from the Coast Guard in August 1994. For the following five years, the vessel remained in reserve at the Coast Guard Yard at Curtis Bay, Maryland. Then, in August 1999, the vessel was recommissioned. How Vindicator was used from this time, until it was decommissioned again by the Coast Guard in May 2001, remains unclear exactly.

The third act in the vessel’s story, before it was recently put up for auction, came when it was transferred to the NOAA in October 2001. It wasn’t until September 2003 that the new vessel was commissioned, with the new name Hi’ialakai (a Hawaiian word meaning “embracing pathways to the sea”). The NOAA’s flagship ocean research vessel, Hi’ialakai was designed to study, monitor, and protect the coral reefs of Honolulu, Hawaii, through coral reef ecosystem mapping, assessment, and monitoring.

During the period between October 2001 and September 2003, Hi’ialakai was given a $4 million refit in order to perform its new ocean research mission. The vessel was co-sponsored by the late Margaret Shinobu Awamura, wife of Hawaii’s then-senior senator Daniel Inouye, and Isabella A. Abbott, professor emerita at the University of Hawaii.

As documentation provided by the GSA on its auction page indicates, Hi’ialakai was packed with a whole host of equipment to support its ocean research mission, including multibeam sonar and echo sound equipment for underwater mapping work. Although now “obsolete and no longer supported by the manufacturer,” the documentation indicates, this included the Kongsberg Maritime multibeam EM300 and EM3002 sonars. The 30 kHz EM300 is capable of surveying to depths of 3000 meters, while the 300 kHz EM3002 is capable of surveying to depths of 150 meters.

In addition, the vessel features a host of navigational systems, as well as a 46-foot telescoping boom with a designed lifting capacity of 6,600 pounds at full extension on deck. The full list of equipment on board (and being sold with) Hi’ialakai, compiled by the GSA, can be seen below.

Hi’ialakai was designed to support up to 50 personnel on board, split almost evenly between officers/crew and scientists, and featured a wet and dry laboratory and an electronics laboratory. The vessel also boasted specialized diving equipment (including a three-person decompression chamber) affording scientists the opportunity to participate in deep-water dive projects. It also can carry its own little armada of rigid-hull inflatable boats (RHIBs).

Ultimately, Hi’ialakai was officially decommissioned by the NOAA in December 2020 after a period of inactivity in 2019. During its latter years with the NOAA, extensive corrosion, pipe failures, and propulsion problems were discovered onboard — a perfect fit for the next-generation Belafonte.

Whichever bidder ends up winning the auction – if the reserve is indeed met – will clearly need some serious funds to bring Hi’ialakai back to life. But, if you’re interested, it may just be the closest you’ll get to living like Steve Zissou on the Belafonte for real.

Contact the author: oliver@thewarzone.com