The U.S. Army is no longer pursuing a new interceptor for its Patriot surface-to-air missile systems. The disclosure as the service has also said it wants to reduce reliance on the highly in demand and heavily strained Patriot force and look more at tailored air defense force packages leveraging its Integrated Battle Command System (IBCS) network.

Army Brig. Gen. Frank Lozano announced the decision regarding what had been known as the Lower-Tier Future Interceptor (LTFI), in a live interview with Defense News‘ Jen Judson from the floor of the Association of the U.S. Army’s (AUSA) main annual conference. Lozano is head of the service’s Program Executive Office for Missiles and Space.

“So, right now, the Army has decided that we are not going to move forward on what we were calling a Lower Tier Future Interceptor,” Lozano told Judson. “That was going to be a very expensive endeavor. … Interceptors in that family or class of interceptors are very capable, but also very expensive.”

The Army had previously defined “lower-tier” in this instance as the “lower tier portion of the ballistic missile defense battlespace” and described the LTFI as being set to help “increase Air and Missile Defense (AMD) capability through increased velocity, altitude, and maneuverability.”

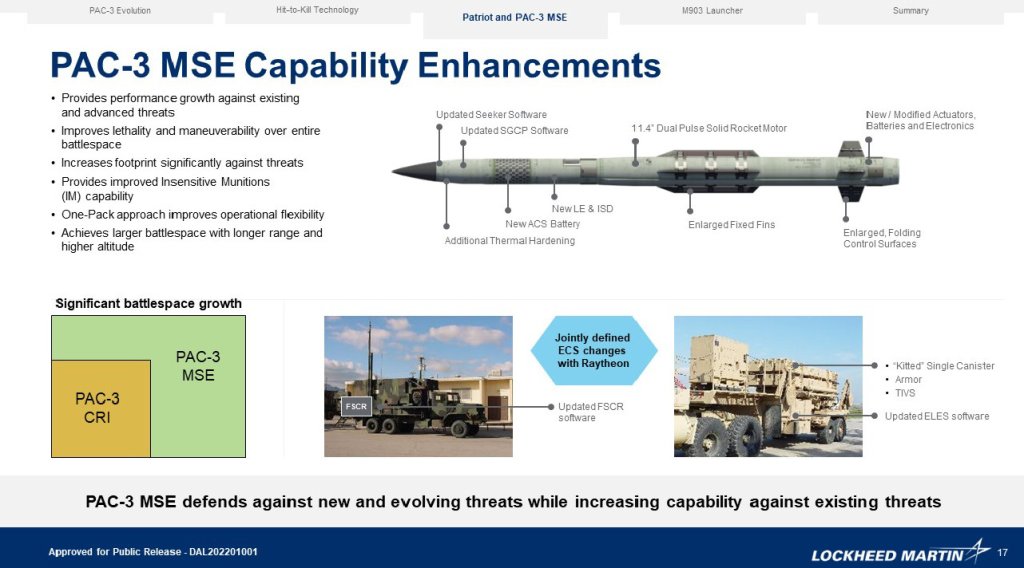

Lozano did not elaborate on cost, but the unit price of a PAC-3 Missile Segment Enhancement (MSE) interceptor, the most advanced type now available for Patriot, is just under $4.2 million, according to Army budget documents.

“After going through a business case analysis within the PEO and with the Army senior leaders, what we’ve decided to do is, one, look at continuing to upgrade the PAC-3 MSE missile, which I believe is probably the best air defense missile in the world, [and] continue to advance that capability so that it can remain relevance against the evolving threats,” Lozano added.

The PAC-3 MSE is already a substantial improvement over precious PAC-3 variants, as you can read about in more detail here. Current Patriot launchers can also be loaded with a mix of PAC-3 MSEs and older interceptor types.

A complete Patriot battery today can consist of up to eight launchers, along with an AN/MPQ-65 multifunction phased array radar and various fire control, communications, and other support equipment. The Army is also in the process of adding a new radar, called the Lower Tier Air and Missile Defense Sensor (LTAMDS), to the Patriot ecosystem.

In addition, Lozano said that the Army has been looking more at how the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) ballistic missile defense system can directly complement Patriot thanks to the new ICBS network. Developed by Northrop Grumman, IBCS is designed to offer an open-architecture command and control and networking environment to link together various air defense sensors and effectors, as you can learn more about here.

“What that would allow us to do is create a tighter coupling between the THAAD system and the Patriot system and via that tighter coupling, then you can manage the battle space in a much more efficient way,” Lozano told Judson. “You could launch a THAAD interceptor against a particular target and then, as backup, launch a PAC-3 interceptor and it opens up the amount of battle space that you can use to take advantage of two interceptors against a very stressing threat… and in that same vein maintain the magazine depth of both family of interceptors.”

The Missile Defense Agency (MDA), in cooperation with the Army and others, has been experimenting with the integration of components of the THAAD and Patriot systems in recent years.

The decision to axe the LFTI effort also highlights broader discussions the Army is having now about the future of its Patiort force, which has been and continues to be in extremely high demand, but also too small to adequately meet those operational needs. The total number of THAAD batteries is even smaller and that system is also managed outside of the Army by the MDA. These are issues The War Zone has highlighted in the past, including just yesterday in the context of the emergency THAAD deployment to Israel.

The Army is looking to expand its Patriot force, but also scale back its use.

“We have relied too long on the Patriot system as the centric system to air and missile defense,” Army Lt. Gen. Sean Gainey, head of that service’s Space and Missile Defense Command (SDMC), said during a panel discussion at AUSA yesterday. “We are modernizing now with the short-range air defense and moving forward with our IFPC [Indirect Fire Protection Capability] cruise missile defense, and our improvements to our current system[s], with the integration into IBCS, it will eventually start to relieve that significant stress.”

The IFPC program, and the Enduring Shield system at the center of it, is a particularly significant part of the Army’s broader air and missile defense modernization plans. The primary interceptor for Enduring Shield, which the service is working toward fielding operationally now, is the AIM-9X Sidewinder.

There are already plans for a second interceptor for Enduring Shield that is more optimized for the counter-cruise missile role. The Army has publicly laid out a vision for a design that offers capabilities akin to the AIM-120D Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM), but in the same form factor as the AIM-9X.

Whatever the new interceptor might look like, it could give Enduring Shield an expanded medium-range air and missile defense capability. The Army’s current lack of a surface-to-air missile system in this middle tier has added to the strain on the Patriot force, which has filled this gap since the retirement of the Hawk system in the 1990s.

The Army is also looking to deploy and employ all of its ground-based air defense capabilities in more tailored and potentially disaggregated ways in the future, thanks in large part to the power of the IBCS network.

“The force structure that we are building and growing is tailorable, it’s adaptable, and it is able to kind of flexibly meet whatever needs we have in any hotspot in the world,” Gabe Camarillo, Under Secretary of the Army, said at the same AUSA panel yesterday as Lt. Gen. Gainey. “We can compose this in any shape or fashion.”

“What I want to be able to do is to be able to provide a Chinese menu, if you will, to combatant commanders, so that once they perform their assessment of the threat, they can say, ‘Frank, give me three of those, one of those, 10 of those, four of those,'” Brig. Gen. Lozano, another member of the panel, also said. “And we deliver that capability, integrated and able to function and work together to defeat any threat any given Combat Commander faces.”

There are questions about how realistic this kind of mission-to-mission tailoring of air defense force packages might be in terms of maintaining readiness and cohesion, especially when it comes to training and otherwise preparing disparate units to work together down range. The Army does seem to be betting heavily on the ability of IBCS to allow the rapid fuzing of different air and missile defense capabilities down-range.

At the panel yesterday, Brig. Gen. Lozano shared an anecdote about how lessons learned from the ongoing war in Ukraine are reinforcing the service’s focus on IBCS:

“About a year and a half ago, I took a trip over to Poland to visit Ukrainian soldiers training on the first two batteries of Patriot that we were donating to them. One was a U.S. battery, one was a German battery. Had the privilege of eating lunch with some of those Ukrainian Air defenders. And at the end of that lunch, I asked them, I’m curious, … based on your employment of Patriot, and Avenger, and Hawk, and Stinger MANPAD [man portable air defense] systems, NASAMS [National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile System], how are you managing the battle space to ensure you have the most efficient application of combat power against the threats that Russia is throwing at you. And they said, you know, sir, you’ve hit on our most significant struggle. If there was a way that we had a system that could integrate all of those capabilities that would make us much more effective in that employment of combat power. Do you have something you can give us? And I said, Well, I can’t get ahead of the President. I’m not allowed to offer anything up, but I will tell you that we’ve recognized that same thing. And so when a lot of people ask me, what are some of the most important lessons that we’ve learned from Ukraine, from an air and missile defense perspective, what has been reaffirming to me is that the modernization path that we are on is exactly the right path to be on.”

The video below highlights various Western-supplied and other air defense systems in service in Ukraine, including Patriot.

The fighting in Ukraine has also broadly underscored the importance of layered integrated air defense networks capable of tackling multiple tiers of threats, from kamikaze drones to ballistic missiles, and doing so simultaneously.

Much still remains to be seen about how the Army’s air and missile defense force structure evolves going forward. At the same time, it is clear that major developments in terms of capabilities, as well as tactics, techniques, and procedures, are still on the horizon despite the end of plans for the next-generation interceptor for Patriot.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com