The U.S. Army and the U.S. Navy recently “initiated” a test of a hypersonic weapon, but the U.S. military won’t say whether or not it was a success, what specific system was involved, or even if there was an actual launch. Previous testing of an Army ground-based hypersonic weapon system it is developing in cooperation with the Navy, known as Dark Eagle, has been particularly beset by problems.

The Army has been hoping to begin fielding Dark Eagle within the next two months, around a year later than originally planned, and in the wake three scrubbed test launches last year. In June, the Pentagon did announced a successful test of a common hypersonic missile designed to be used in both the Army’s Dark Eagle and the Navy’s sea-based Intermediate Range Conventional Prompt Strike (IRCPS) weapon systems. To date, there has been no known full end-to-end test of the missile involving a production-representative launch system.

“The U.S. Army and Navy recently initiated a test of a conventional hypersonic system at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida,” a U.S. defense official told The War Zone in a statement. “This test was an essential benchmark in the development of operational hypersonic technology. Vital data on the performance of the hardware and software was collected that will inform the continued progress toward fielding hypersonic weapons.”

“We have no additional details or information [about the test] to provide at this time,” the statement added.

When the Army-Navy hypersonic test occurred exactly is unclear, but public warning notices to aviators and mariners point to it taking place on July 25. Observers using online flight tracking software also spotted aerial activity in line with a missile test from Cape Canaveral on that date. This included the presence of a U.S. Navy NP-3D missile tracking aircraft, one of NASA’s high-flying WB-57F research planes, and specially modified contractor-operated High Altitude Observatory (HALO) Gulfstream business jets. All of these aircraft have aided in hypersonic testing in the past. There is the possibility that an RQ-4 Global Hawk drone specifically modified to support hypersonic tests, something you can read more about here, was also present.

The widespread belief is also that this was a test of the Army’s Dark Eagle weapon system, also known as the Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW), but this has not been explicitly confirmed. Previous attempted Dark Eagle/LRHW tests have been staged at Cape Canaveral.

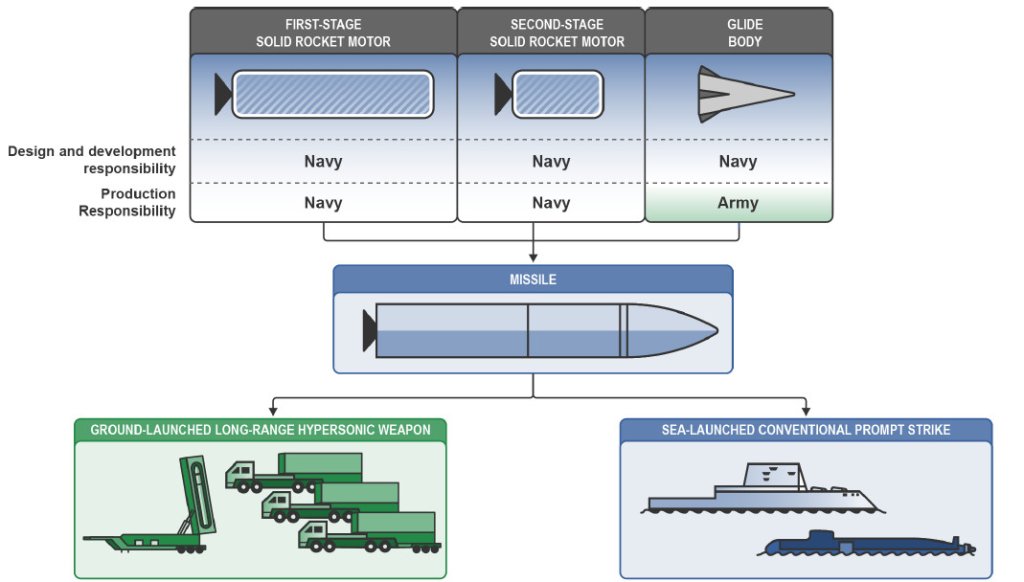

Dark Eagle/LRHW is also one half of the only known joint Army-Navy hypersonic weapon program, which has been ongoing since 2019. The Navy’s IRCPS component is set to be integrated onto the service’s three Zumwalt class stealth destroyers and future Block V Virginia class submarines.

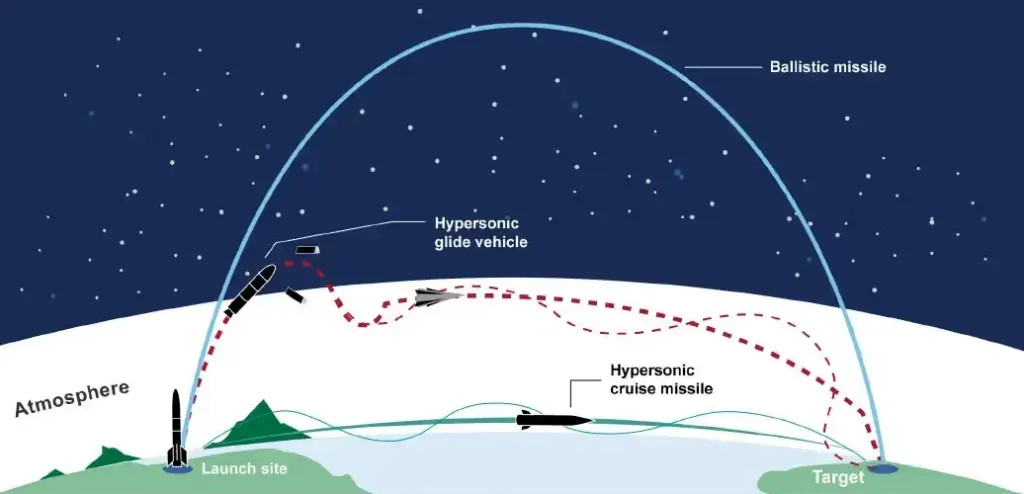

The common missile, or all-up-round (AUR), under development for both Dark Eagle/LRHW and IRCPS is a so-called boost-glide vehicle hypersonic weapon. It consists of a large ballistic missile-esque rocket booster with an unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle on top.

Hypersonic weapons of this type use their rocket booster to get the glide vehicle to an optimal speed and altitude before releasing it. The vehicle then heads to its target via a relatively shallow, atmospheric flight path at hypersonic speeds, which are defined as anything above Mach 5.

The boost-glide vehicle at the tip of the AURs for Dark Eagle/LRHW and IRCPS is a conical design with a high degree of maneuverability. This, together with the weapon’s extreme speed, makes it very challenging for defenders to spot and track, let alone intercept, and reduces the time an opponent has to react in any way.

The Army has said in the past that the weapon, at least when employed in its ground-launched form, is expected to reach a peak speed of at least Mach 17 and have a range in excess of 1,725 miles (2,775 kilometers). The warning notices that are believed to be associated with the recent test from Cape Canaveral suggest the maximum range could be between around 2,112 and 2,796 miles (3,400 and 4,500 kilometers). For traditional ballistic missiles, intermediate-range is generally defined as anything between 1,864 and 3,418 miles (3,000 and 5,000 kilometers).

“Hypersonic systems… provide a combination of speed, maneuverability, and altitude that enables highly survivable, medium and intermediate-range, rapid defeat of time-critical, heavily-defended targets,” the U.S. defense official added in their statement about the recent test event. “The services common hypersonic AUR supports the National Defense Strategy and will provide combatant commanders with diverse capabilities to sustain and strengthen integrated deterrence and to build enduring advantages for the Joint Force.”

When either Dark Eagle/LRHW or IRCPS actually enters operational service remains to be seen. As previously mentioned, the Army aborted three separate attempted tests last year. The service has publicly blamed issues with the ground-based launcher rather than the missile itself for those scrubbed launches.

In 2022, the Navy did test launch one of the common missiles, but it “failed mid-flight,” according to a report just today from the Government Accountability Office (GAO). A previously released report from the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Test and Evaluation had said that the weapon “experienced an in-flight anomaly that prevented data collection for portions of the planned flight profile,” but that “the Navy… determined the cause [and] implemented corrective actions.”

There was the successful AUR test in June, which involved a launch from the Pacific Missile Range Facility in Kauai, Hawaii. A picture from that test, seen below, appears to show the use of a ground-based test stand rather than a more direct surrogate for either the planned ground or sea-based launch modes.

“This flight test of the common hypersonic missile marks a milestone for our nation in the development of this capability,” Vice Adm. Johnny Wolfe, Director of the Navy Strategic Systems Programs office, said after that launch.

“Through our joint efforts, we are developing new equipment and adopting new defense concepts that will enable the Army to maintain superiority over any potential adversaries,” Lt. Gen. Robert Rasch, head of the Army’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office (RCCTO), also said at that time.

The Army had originally hoped to begin fielding Dark Eagle/LRHW by the end of Fiscal Year 2023, which came to a close on September 30 of that year. The service subsequently moved that timeline up to the conclusion of this fiscal year, which is just over two months away now. Earlier this month, U.S. and German authorities also reaffirmed a goal to start “episodic” deployments of Army “conventional long-range fires units,” including ones armed with “developmental hypersonic weapons,” to the latter country as soon as 2026.

The initial Dark Eagle/LRHW unit – Battery B, 5th Battalion, 3rd Field Artillery (Long Range Fires Battalion), part of the 1st Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF) – has already been stood up at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington State. Earlier this month, the unit took part in Resolute Hunter 24-2, the latest iteration of “the Department of Defense’s only dedicated battle management, command and control, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance exercise.”

The Navy has been and continues to plan to start deploying IRCPS on Zumwalt stealth destroyers in 2025 and on Block V Virginia class submarines in 2028. Whether any ongoing testing woes might be threatening to upend those plans is unknown, but the USS Zumwalt is already in the process of being refitted to employ the missiles. The process involves removing the existing 155mm Advanced Gun Systems and their stealthy turrets from those ships.

U.S. military hypersonic weapons programs beyond Dark Eagle/LRHW and ICRPS have been facing uncertainty in recent years, as well. The U.S. Air Force’s Air-launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW) program, which had been developing an air-launched hypersonic boost-glide vehicle weapon that was originally expected to enter service in 2022, has officially come to a close. However, there are signs that a follow-on effort might be in the works, if it hasn’t already started in the classified realm. The Air Force had previously said it was shifting away from ARRW to focus its efforts on the development of an air-breathing Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile (HACM). However, there have been indications that the HACM program, which is intertwined with efforts to help Australia develop a similar, if not identical weapon, has been facing its own challenges.

The U.S. military’s statement about the latest Army-Navy hypersonic weapon test (or attempted test) only adds to the questions about the future of the Dark Eagle/LRHW and IRCPS weapon systems. The Army’s desire to start fielding the hypersonic missiles by the end of September looks increasingly uncertain, at best, given the continued lack of a fully representative end-to-end test, at least that we know of.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com