The U.S. Army has finally test-fired its Dark Eagle hypersonic missile from its trailer-based launcher, something it has been attempting to do for some two years now. The service has explicitly blamed problems with the launcher for causing major testing woes that have pushed back plans to field the weapon system by years.

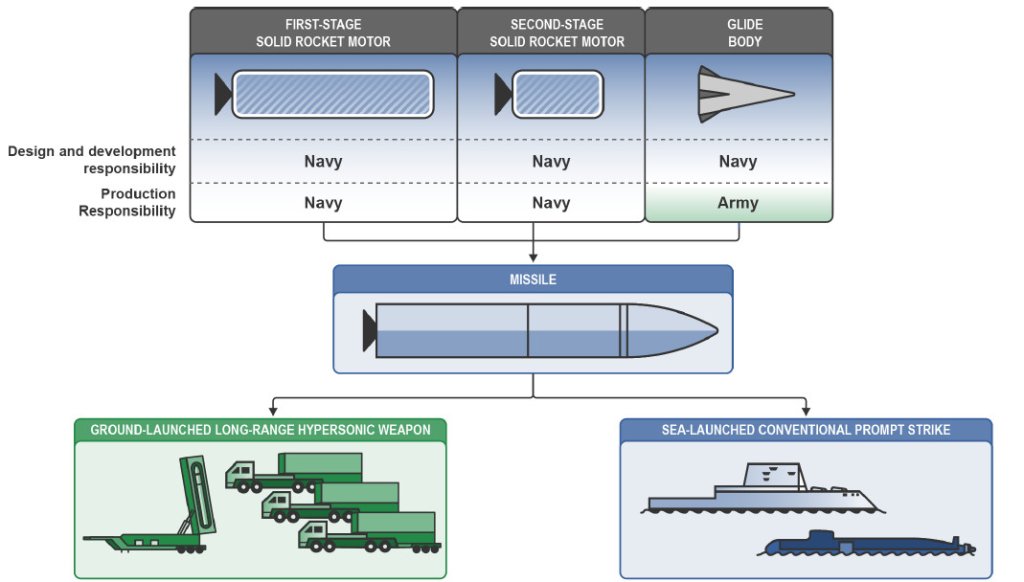

The Army’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office (RCCTO), together with the U.S. Navy Strategic Systems Programs, conducted the test launch from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida, according to a Pentagon press release this evening. The missile at the core of Dark Eagle, also known as the Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW), is the same one the Navy plans to arm its Zumwalt class stealth destroyers and future Block V Virginia class submarines with. The two services have been working together to develop their respective systems. You can read more about the Navy’s progress on its Intermediate Range Conventional Prompt Strike (IRCPS) weapon system here.

“This is the second successful end-to-end flight test of the [common] All Up Round (AUR) [missile] this year and was the first live-fire event for the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon system using a Battery Operations Center and a Transporter Erector Launcher,” according to the Pentagon release, which does not explicitly say when the test occurred.

However, spotters were able to use publicly available warning notices, flight tracking data, and NASA camera feeds from Cape Canaveral to catch the launch occurring earlier today. Online flight tracking shows that one of NASA’s WB-57F aircraft, a Navy NP-3D range support plane, and two specially modified High Altitude Observatory (HALO) Gulfstream business jets operated by the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) were airborne at the time. All of these aircraft regularly make appearances during hypersonic and other missile testing, among other research and development and test and evaluation activities.

“This test builds on several flight tests in which the Common Hypersonic Glide Body achieved hypersonic speed at target distances and demonstrates that we can put this capability in the hands of the warfighter,” Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth said in a statement about the test.

“This test marks an important milestone in the development of one of our most advanced weapons systems. As we approach the first delivery of this capability to our Army partners, we will continue to press forward to integrate Conventional Prompt Strike into our Navy surface and subsurface ships to help ensure we remain the world’s preeminent fighting force,” Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro said in a statement.

“This test is a demonstration of the successful Navy and Army partnership that has allowed us to develop a transformational hypersonic weapon system that will deliver unmatched capability to meet joint warfighting needs,” Navy Vice Adm. Johnny R. Wolfe Jr, director of the Navy’s Strategic Systems Programs that is leading work on the common AUR, added.

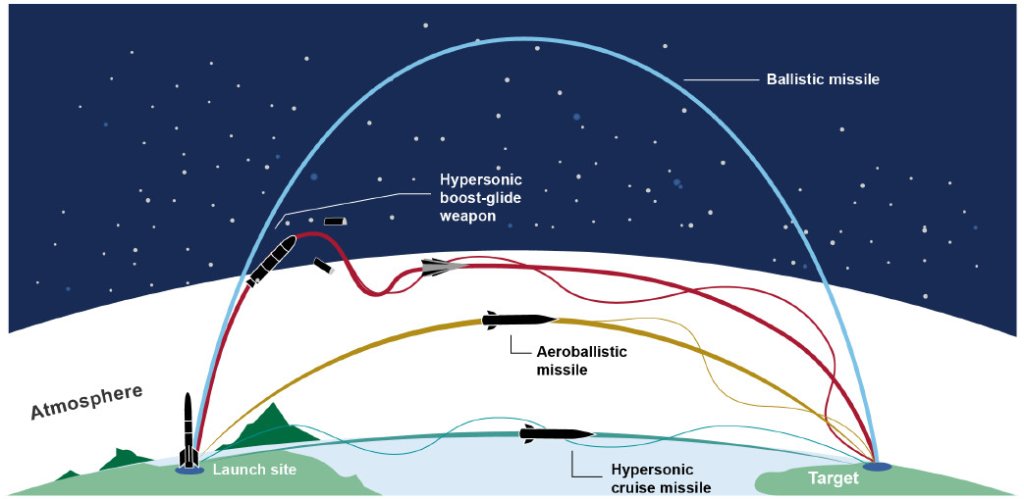

The common missile, or All Up Round (AUR), being developed for Dark Eagle and IRCPS consists of two main components, a two-stage rocket booster with an unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle on top. As designed, the missile gets the conical ‘vehicle’ to an optimal speed and altitude before releasing it, after which it glides down to its target at hypersonic speeds, defined as anything above Mach 5, and along a relatively shallow, atmospheric flight path, maneuvering erratically along the way. The Army has previously said the weapon’s peak speed is at least Mach 17 and its maximum range is in excess of 1,725 miles (2,775 kilometers).

“Hypersonic systems … provide a combination of speed, maneuverability, and altitude that enables highly survivable, medium and intermediate-range, rapid defeat of time-critical, heavily-defended targets,” a U.S. defense official told The War Zone after another test event earlier this year. “The services common hypersonic AUR supports the National Defense Strategy and will provide combatant commanders with diverse capabilities to sustain and strengthen integrated deterrence and to build enduring advantages for the Joint Force.”

While firing a missile from the Dark Eagle launcher is a major milestone, the fact that it has only come now underscores the problems that have been dogging the system’s development for years. The Army scrubbed three planned launches last year. The Pentagon did announce a successful end-to-end common AUR test in June, but that had made use of a different ground-based launch apparatus.

“The U.S. Army and Navy recently initiated a test of a conventional hypersonic system at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida,” a U.S. defense official told The War Zone in a statement in July, but offered no further details at the time. Thanks to today’s Pentagon press release, which says the test involving the Dark Eagle launcher was the “second successful end-to-end flight test of the All Up Round (AUR) this year,” we now at least know whatever happened in July did not involve an end-to-end demonstration of the common Dark Eagle/IRCPS missile.

As noted, the Army has blamed past Dark Eagle testing woes on unspecified issues with the launcher rather than the missile.

When Dark Eagle might actually enter service is still an open question. “Based on current test and missile production plans, the Army will not field its first complete LRHW battery until fiscal year 2025,” the Government Accountability Office, a Congressional watchdog, said in a report released in June. Fiscal Year 2025 began on Oct. 1, 2024.

The Army had previously hoped to have a prototype battery start live-fire testing of Dark Eagle in Fiscal Year 2022 and field, at least on a limited level, in Fiscal Year 2023. The initial Dark Eagle unit – Battery B, 5th Battalion, 3rd Field Artillery (Long Range Fires Battalion), part of the 1st Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF) – has already been activated at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington State.

After the ostensible cancellation of the U.S. Air Force’s AGM-183A Air-launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW) program last year, Dark Eagle had looked set to be the U.S. military’s first operational novel hypersonic weapon. There is still some uncertainty surrounding ARRW status and there may be plans for a follow-on effort, if it hasn’t already begun in the classified realm. The U.S. military as a whole has and continues to stress the importance of developing and fielding hypersonic boost-glide vehicle weapons, as well as air-breathing hypersonic cruise missiles, to ensure its ability to successfully prosecute various targets set on land and at sea going forward. These capabilities are seen as especially critical for success in a potential future high-end fight in the Pacific against China. There are also now plans for “episodic deployments” of ground-based hypersonic and other long-range missile systems to Europe.

The Navy hopes to begin at least live-fire testing of its IRCPS system from the USS Zumwalt, which is in the final stages of being modified to fire the missiles and just recently returned to the water after months in dry dock (as seen below), in the current fiscal year.

It remains to be seen now if Dark Eagle’s path to an operational capability is more clear cut following its first successful launch using the trailer-based launcher, but it certainly is a good sign that the program can move forward toward fielding.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com