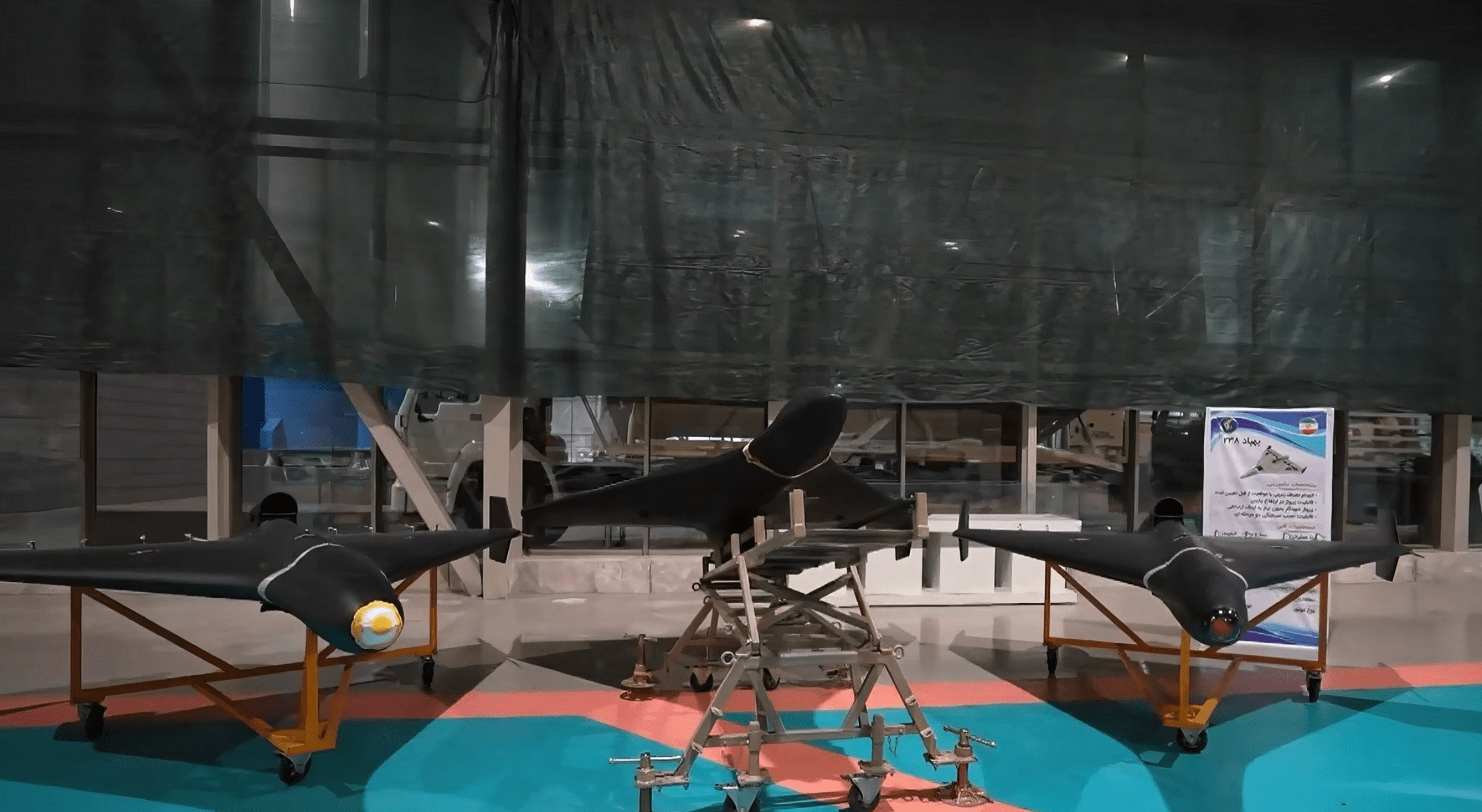

Iran has officially presented a new version of its notorious Shahed ‘kamikaze drone,’ now powered by a jet engine rather than the previous piston-propeller arrangement. The Shahed-238 was also shown with new guidance systems, with radar and electro-optical/infrared guidance now apparently being offered in addition to earlier Shahed versions, which primarily employed a combination of inertial and GPS navigation to hit fixed targets.

The Shahed-238 was displayed on the ground during an “aerospace achievement exhibition” organized by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), at the Ashura Aerospace Science and Technology University, in Tehran, on November 19. The exhibition was attended by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who was shown a variety of different Iranian drones and missiles.

A video showing Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei visiting the Ashura Aerospace Science and Technology University, in Tehran, on November 19:

The existence of the jet-powered drone was first revealed back in September.

Developed on the basis of the Shahed-136 drone, which has been widely employed by Russia in Ukraine, three examples of the Shahed-238 were on display, representing the three different guidance options. One of these is thought to feature an anti-radiation seeker. Although this remains unconfirmed, a similar seeker is thought to be available for the Shahed-136. If correct, this version of the Shahed-238 would be intended to home in on hostile radio-frequency transmitters, especially air defense radars, allowing it to be used for the suppression/destruction of enemy air defenses (SEAD/DEAD) missions.

An active radar seeker is also possible. This would be a major technological boost, but the actual capabilities of it are not clear. If this is indeed an active radar seeker, it could theoretically allow the drone to hit moving targets in all weather, although how it would initially find the right target after flying a significant distance from its launch to its target area is unknown. Some sort of autonomous target recognition would be needed. Perhaps this would be most valuable for anti-surface/anti-ship applications which eliminates some of these challenges.

The operating mode of the version with electro-optical/infrared guidance is unclear. Some reports suggest this uses a passive infrared sensor to autonomously home in on heat sources, while others describe a man-in-the-loop system, with an operator using video fromt the sensor to guide the missile to its target. This would also likely impose a range restriction, based on the need to maintain a link between the drone and operator throughout the engagement.

It remains the case that we don’t know for sure what kinds of guidance modes are actually used and to what degree they have been tested, let alone whether they are currently available. However, these guidance systems have already been fielded on other Iranian missiles and drones, so it’s clearly a possibility.

Interestingly, a video shown as part of the exhibition in Tehran included footage of the test launch of a Shahed-238 from the roof of a moving pickup truck — although it’s assumed that operational versions of the drone will be able to employ the same rocket-assisted takeoff as used by the Shahed-136. The drone shown in that video is fitted with a ball-like electro-optical sensor turret below the nose. This gimballed housing suggests the sensor here is intended primarily for surveillance and possibly combined strike missions. This additional payload would further decrease the range, but that would not be a major issue bearing in mind the man-in-the-loop guidance and sensor control necessary for this type of configuration.

All three of the Shahed-238 drones were also finished in an unusual matte black color scheme. While this has led to some speculation that they may have had some kind of treatment with a radar-defeating coating or paint, it may simply reflect the fact that these kinds of drones are now mainly intended for nighttime attacks, as seen in the tweet embedded below. However, any kind of reduced radar signature would clearly make the Shahed-238 a tougher target for air defenses. Getting rid of the exposed internal combustion engine and prop (although wood/composite is typically used) will also lower the drone’s radar cross-section, possibly significantly. Although, on the other hand, the jet exhaust will also contribute to a boosted infrared signature, especially when viewed from the rear aspect.

While no details were provided regarding the specification of the Shahed-238, the jet propulsion will ensure significantly higher speed and fast transit to target times, which is is a big factor when trying to go after more time sensitive targets. Although, the jet engine will also impact the range, unless additional fuel capacity has also been introduced. It will be interesting to see if the warhead size has been reduced to add more fuel, even if relatively small amounts.

The basic Shahed-136 reportedly has a maximum range of 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles) and a cruising speed of 180km/h (111mph), about the same speed as a Cessna 152.

Photo by YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP via Getty Images

The jet-powered Shahed-238 will also be more expensive than piston-engine versions. The low price point of these drones has always been an advantage. For example, a Shahed-136 about $20,000 a piece to make, The New York Times has stated. Meanwhile, a single AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM) fired by one of Ukraine’s National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (NASAMS) that have shot down plenty of Shaheds costs roughly between $500,000 and $1 million.

Even if the price of the Shahed-238 is hiked up, it will still be far cheaper than a cruise missile, and would also be affordable enough to allow mass attacks on its chosen targets.

With earlier, propeller-driven versions of the Shahed having been widely used by Russia in Ukraine, the appearance of a new modification of the drone has led to comments from Ukrainian officials, including Yuriy Ignat, spokesman for the Ukrainian Air Force.

“Now there is news that Iran is producing a new Shahed with a jet engine, with different radar guidance,” Ihnat said. “There are different options… It is painted in a matte black color, which can also complicate the work of visual detection. I don’t know if Russia will receive them, but these countries have such experience.”

With Russia having stepped up its use of Shahed-136 drones in recent months, ahead of an expected onslaught against Ukrainian energy infrastructure, the potential availability of new versions of the drone could be very welcome for Moscow. At this time, it’s unclear what stage of development the Shahed-238 is at, not to mention whether Russia is actively pursuing its procurement.

What is clear is that Russia has been refining the tactics it uses with its Shahed-131 and Shahed-136 (known in Russia as Geran-1 and Geran-2), as well as introducing improved versions of these. In September, we reported on how a new type of Shahed-136 drone was being used, featuring a warhead packed with tungsten balls, according to Ukrainian officials. This should produce a more destructive fragmented shrapnel effect.

As well as new warheads, improved versions of the Shahed have also been found to contain new engines, batteries, servomotors, and bodies, according to Capt. Andriy Rudyk, a representative of Ukraine’s Center for the Research of Trophy and Prospective Weapons and Military Equipment.

At the same time, Russia has reportedly launched domestic production of Shahed drones.

“Unfortunately, Russia now has the opportunity to manufacture its own,” Yuriy Ignat said, back in September, “This is a new challenge against which we will respond. It is likely they will start attacking energy infrastructure again.”

At the same time, there remains a question about how much of the Russian-made Shahed drone actually comprises components from domestic production. In the past, Iranian-made Shahed drones had been found to contain certain Russian-made components, including guidance systems and batteries, suggesting that the country was gearing up for full-scale local production.

In August, we published new details about a Russian plan to domestically build 6,000 Shahed-136 (Geran-2) drones by 2025. These were to be built in a facility 500 miles east of Moscow in the Tatarstan region. You can read more about that in our story here.

While this goal is very likely over-ambitious, there’s no doubt that Russia is looking to increase the numbers and capabilities of Shahed-type drones in its service. Offering improved performance, at last in terms of speed, as well as different guidance options, the Shahed-238 would certainly be of extreme interest to Russia, based on its previous experience with drones of this kind in the Ukraine war. Russian dollars could be funding its rapid development, even.

For Iran, too, as well as the various proxies that it has provided with kamikaze drones, across the Middle East, the Shahed-238 will likely also provide a boost in capabilities. In this theater, Shahed drones, as well as smaller Iranian delta-wing uncrewed aircraft designs, have made a significant mark, perhaps most notably in the infamous drone and missile strikes on oil infrastructure in Saudi Arabia in 2019.

After all, while the Shahed-136 has a very impressively long range, in many cases, this isn’t required to hit the targets chosen. A jet-powered version of the same drone would be much faster and more survivable. Already, the baseline Shahed drones have been a major headache for Ukrainian air defenses, proving tricky targets for ground-based systems and fighter aircraft alike.

Much of the difficulty in countering the Shahed-131/136 comes from the fact that they are small and low-flying, as well as appearing in significant numbers, while the Shahed-238 would be a tricky target due to its combination of small size, black paint, and high speed. With Ukraine relying heavily on drone-hunting teams equipped with searchlights and rudimentary anti-aircraft guns, to defeat the Shahed threat, a faster kamikaze drone will be a far tougher proposition for these teams.

Even more advanced air defenses will be more challenged by much higher-performance Shaheds. Reduced reaction times would make taking them out tougher, especially when employed in large numbers and when part of layered attacks that can include both types of Shaheds, as well as cruise and ballistic missiles.

At the same time, being available with different guidance options could make it harder to defeat the drones using non-kinetic means, like electronic jamming, in certain cases.

With Russia seemingly running low in terms of its conventional cruise missile arsenal, a more survivable Shahed would also help address that issue, at a fraction of the cost of a long-range missile.

It remains to be seen if jet-powered Shaheds end up on the battlefield in Ukraine, but they clearly would be a troubling development for Ukraine’s over-taxed air defenders to content with if they do.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com