The so-called ‘just-in-time’ logistics model that stealthy F-35 Joint Strike Fighters rely entirely on, particularly when it comes to spare parts, would present major risks in a large-scale conflict, according to the top U.S. officer in charge of the program. While that is troubling, it is hardly surprising. Unfortunately, even after years of major problems being readily apparent, the F-35 program continues to face significant supply chain hurdles that could seriously hamper the jets’ ability to perform sustained high-end combat operations against a major foe like China. Here’s why.

Air Force Lt. Gen. Michael Schmidt, the current head of the F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO), raised his specific concerns about the just-in-time concept during a panel discussion on April 3, at the Navy League’s annual Sea-Air-Space conference and exhibition. Other U.S. officials, as well as industry representatives and foreign military officers, raised similar and otherwise related points during that talk and during other recent events.

The complexities and ballooning costs of sustaining F-35 fleets have been growing issues for years now.

“This program was set up to be very efficient… [a] just-in-time kind of supply chain. I’m not sure that that works always in a contested environment,” Lt. Gen. Schmidt said. “And when you get a just-in-time mentality, which I think is it’s kind of a business model in the commercial industry that works very well in terms of keeping costs down and those kinds of things, it introduces a lot of risk operationally.”

The biggest risk is that F-35 units have little in terms of spare parts on the shelf to keep their aircraft flying for any sustained amount of time.

This is a headache during peacetime and impacts readiness and training, but during a time of war, it means that any disruption in the logistical train will result in unusable aircraft very quickly. And even if deployed units get extra parts early on, getting more to them, or having them on hand anywhere when the F-35 fleet will be sucking up massive amounts of spares, is highly questionable.

Many billions of dollars invested in top-of-the-line stealth fighters could well be wasted with those aircraft being taken out of the fight early in a conflict – not due to enemy fighters or surface-to-air missiles, but because of a lack of spare parts ready and waiting nearby on the shelf. It sounds ironic, but that is a potentially glaring reality at this time.

Just-in-time is not enough

Just-in-time supply chains are indeed commonly used in the commercial aviation industry, among many others.

This “strategy aligns raw material delivery to specific production cycles so that materials arrive as production is scheduled, but no sooner,” the video below from computer technology company Oracle explains. “This ensures there is only enough stock to produce what’s needed when it’s needed with the goal of achieving high-volume production with minimal inventory on hand and eliminating waste.”

“Businesses using a just-in-time strategy need to meticulously plan their production processes, fine-tune visibility into their supply chain, and ensure demand forecasting is accurate,” the video adds.

The same concept carries over to actually delivering finished items to where they are consumed. In terms of aircraft, this would be where it is serviced and repaired, whether that be in the field at forward locations or at a depot or major service center.

In a commercial context, such as an airline, a just-in-time model makes good sense in many ways. While the aircraft in their fleets might be complex, they have typically demonstrated a high degree of reliability in the course of very high routine usage. From that usage, massive amounts of data are produced that can be used to more accurately predict what parts are needed when and where. In addition, though an airline’s aircraft may operate from hundreds of well-established airports globally on a regular basis, stockpiling spare parts at each one would be cost-prohibitive.

Interestingly, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impacts on global supply chains, especially sea-based ones, there has reportedly been a movement away from just-in-time logistics for commercial purposes, at least to some degree.

Regardless, in a military context, aviation units often have to be prepared to deploy and operate very complex aircraft like the F-35 from a wide variety of sites, possibly including remote and austere ones with limited infrastructure, all under combat conditions. Lt. Gen. Schmidt and others are increasingly arguing that ‘just-in-time’ will never be reliable enough to support these kinds of deployments, especially given the U.S. military’s increasing focus on distributed operations at irregular intervals to reduce vulnerability and upend enemy planning cycles.

“When you have that [just-in-time] mentality, a hiccup in the supply chain, whether it be a strike … or a quality issue, and then that becomes your single point of failure,” the F-35 program head explained.

This matters because major hiccups for any reason in the supply chains can quickly translate to shelves that should be stocked with spares emptying out, even just as a result of routine preventive maintenance demands. When it comes to F-35 units, this, in turn, can lead to a drop in sortie rates and force maintainers to cannibalize aircraft to keep other jets flying.

If the situation persists, this can have cascading impacts. Aircraft sitting idle for extended periods of time can present additional challenges when it comes to returning them to service. Units that develop a maintenance backlog could easily need a higher-than-average number of spare parts to get things leveled out, creating additional logistical strains.

So, “that’s exactly what we need to look at, what does ‘right’ look like in the future, to give us more resiliency in a combat environment,” Lt. Gen. Michael Schmidt said.

Fixing the parts problem

The just-in-time model has presented serious issues when it comes to supporting Joint Strike Fighters in far less strenuous peacetime environments already. This has led to a domino effect on maintenance workflow and, in turn, on readiness rates across the F-35 fleets within the U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps.

The obvious immediate course of action would seem to be to change how the U.S. military purchases, stockpiles, and distributes F-35 spare parts. Speaking alongside Lt. Gen. Schmidt and others at the panel on Monday, Bridget Lauderdale, vice president and general manager of the F-35 Lightning II Program at Lockheed Martin, talked about how the company is working with the rest of the supplier base to get better visibility on what is needed where and when, and otherwise improve the overall process.

“One of the things we’ve done is put a lot of energy in modeling and understanding, forecasting, predicting the demand signal so that we get it right,” Lauderdale. “A lot of these materials [required to make certain parts] take lead time to prepare… even when you have repair capacity.”

Lauderdale further highlighted a shift to performance-based logistics contracting to help better incentivize suppliers to be better prepared to meet changing demands for certain spare parts with the help of this additional forecasting data.

“It takes time for these things to manifest through the supply chain, but [we] have been successful in a couple of performance-based logistics contracts with suppliers so that they are accountable for the demand signal, they determine the size of their footprint,” Lauderdale explained. She said the hope was that these deals would also improve the overall supply chain’s flexibility. This could include adding options to repair certain parts rather than replace them entirely, which could be a more cost-effective and timely course of action depending on the circumstances.

As Lauderdale acknowledged, it remains to be seen exactly how these changes will impact the F-35’s supply chains. The fact that they are only being implemented now, despite spare parts shortages and related issues being well-known across the Joint Strike Fighter program for years now, in part due to past mismanagement, underscores the complexities at play.

The F-35 by itself is complicated to manufacture and maintain, with some core components taking months or even years of lead time to produce. As such, even a schedule slip for any reason in the current just-in-time model can immediately create issues.

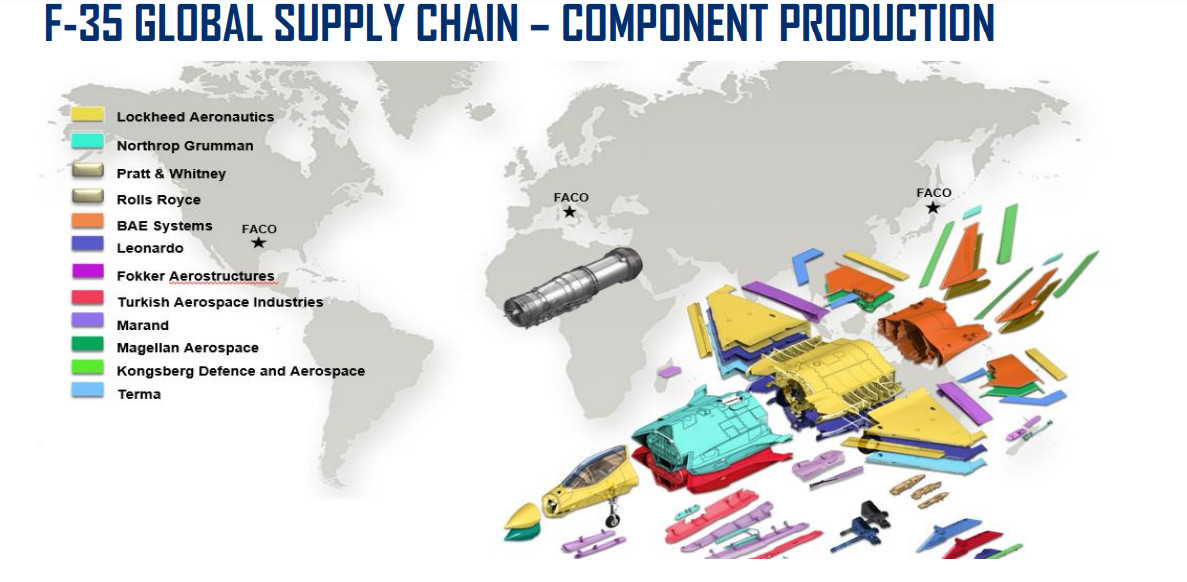

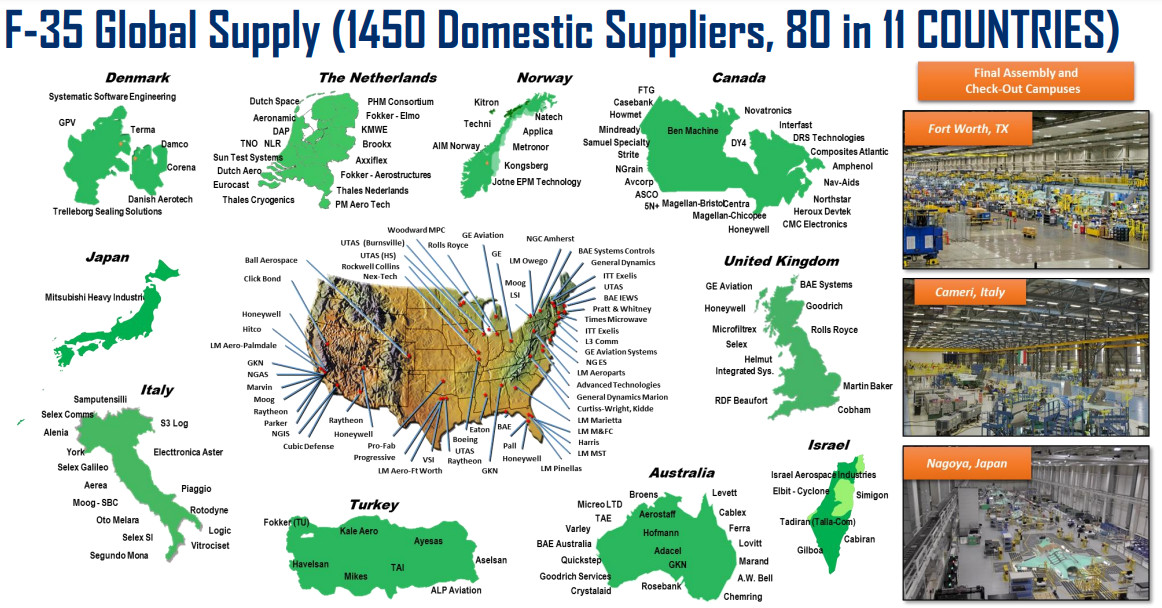

On top of that the overall program, which dates back to the late 1990s, is unique in many ways. How the aircraft was developed and the very deep integration of a number of foreign partners who contribute directly to global supply and maintenance infrastructures has had pronounced effects on the evolution of the supply chain infrastructure.

The ghost of concurrency

The legacy of a process known as “concurrency” in the F-35 program, at least in the past, has created immediate additional hurdles when it comes to the supply of spare parts. Concurrency in this context refers to the Pentagon’s decision to approve low-rate production of hundreds of F-35s despite the design not being finalized in many respects, with the idea that necessary upgrades would be integrated into the jets on a rolling basis as time went on. This was presented as a cost and time-saving measure, but it proved to be anything but.

Though efforts have been made to stabilize the situation, F-35 jets across the U.S. military continue to exist in many subconfigurations, both in terms of hardware and software. The differences between very early jets and more recent production examples are so significant that it has become cost-prohibitive to continue to upgrade many of the former aircraft. Depots have also been clogged with older jets needing key fixes and enhancements to bring them up to speed. Some of the oldest types may only be used for a fraction of their planned service lives.

When it comes to sustainment, this means that spare parts and general maintenance procedures are not necessarily common across the fleet. The Marine Corps found this out in 2018 during its first two deployments of F-35Bs onboard Navy amphibious assault ships. It turned out that less than half of the spare parts that the amphibious assault ships USS Wasp and USS Essex had on board were compatible with the specific jets they were hosting, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a congressional watchdog.

Deployed F-35 units have since been given higher priority for spares to help alleviate such issues, but this doesn’t address the underlying limitations of the existing supply chain.

Concurrency, together with other factors, has led to a number of important parts wearing out sooner than expected. Last week, Lockheed Martin’s Lauderdale said that approximately 90 percent of the parts that go into the F-35 family either met or exceeded reliability expectations. However, 10 percent of parts not meeting those expectations is still significant and has negative impacts on supply chains supporting the Joint Strike Fighter, as well as the overall readiness of U.S. fleets of these jets.

“The demand signal is generated by models that we continually update. I would say, specific to the model themselves, we have relied on the reliability predictions in engineering at the beginning of the program,” Lt. Gen. Schmidt said on Monday. He added that it was very important to acknowledge that some of those predictions had proven to be more accurate than others.

This has all been particularly pronounced when it comes to the Pratt & Whitney F135 engine variants that power all F-35s.

Engine issues

While testifying before a subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee in March, Schmidt had disclosed that the F-35’s engine has been “under spec since the beginning.” This means it has to run hotter than originally planned for extended periods of time to meet current power and cooling requirements, which causes increased wear and tear. This has, not surprisingly, increased maintenance demands and created a backlog that has been sidelining jets at a worryingly high rate for nearly two years now at least.

A written statement that Jon Ludwigson, GAO’s Director of Contracting and National Security Acquisitions, submitted ahead of the same subcommittee hearing in March says that the F135 engine woes have added an estimated $38 billion to the overall cost of the F-35 program. As of last year, GAO pegged the total expected cost of the F-35 program across its complete lifecycle, which is expected to stretch out to at least 2064, at around $1.7 trillion.

The rollout of the Pentagon’s 2024 Fiscal Year budget proposal last month included the announcement that the F-35 JPO had decided against plans to re-engine at least some F-35s in favor of a less intensive upgrade program. It is still expected to take at least five to six years, and an untold amount of additional funding, for the development of this Engine Core Upgrade (ECU) to be completed. You can read more about all of this and the aircraft’s hot-running engines in our previous report here.

ALIS in Wonderland

The F-35 program long sought to mitigate many of these demand signal and parts reliability issues through a centralized cloud-based ‘computer brain’ called the Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS). One of the core functions of ALIS, components of which live on each F-35 and in computer systems on the ground that connects to the cloud, is to try to help predict maintenance and logistical requirements. As designed, ALIS, which you can learn more about here, also serves as the central node through which key pre-mission and post-mission data would be uploaded and downloaded from the aircraft, among many other functions.

ALIS, a complete cloud-based ecosystem, was expected to be able to leverage a constant flow of data from across the U.S. and foreign F-35 fleets. This was supposed to help provide a keen sense of logistical demands, including information that would help revise the understanding of what parts might be susceptible to increased wear or otherwise be failing sooner than expected. Real-time health monitoring of the jet would detect degrading components and automatically flag them for replacement.

Unfortunately, over the years, ALIS has proved to be riddled with issues, exacerbating maintenance and logistics backlogs. Maintainers have been forced to use obtuse workarounds making things more complicated, not less.

Furthermore, ALIS has turned out to be so intrusive in what data it collects that many foreign operators took steps to firewall off portions of their other networks from it. All of these issues have also limited the reliability of the data on supply chain demands that ALIS can provide. Without highly reliable data entering the system, the resulting actions based on that data would suffer, as well.

The F-35 JPO ultimately decided to abandon efforts to fix the system in favor of a completely reworked architecture called the Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN). That replacement system is still in development.

There are questions about how much the Technology Refresh 3 (TR-3) and Block 4 upgrade programs may further complicate all of this in the coming years. These modernization efforts are set to bring substantial new capabilities to U.S. F-35 fleets, and those belonging to at least some foreign operators. They also involve substantial changes to the aircraft’s configuration, including the addition of an all-new radar and an improved electronic warfare suite, among many other enhancements.

Parts of the parts problem

Production capacity and quality control issues have long dogged efforts to increase and otherwise streamline the purchase of additional spare parts to help mitigate these issues. In his remarks Monday, Lt. Gen. Schmidt notably described the potential for a “quality issue” in the supply chain to be just as disruptive as an outright enemy strike.

Production and quality problems sometimes have cascading impacts, too. An additional contributor to the shortage of F135 spare parts, for instance, has been the growing demand for additional examples of these engines to go into new-production F-35s.

“When we start to up the numbers of the actual planes rolling off the line, one of the issues we had is to make sure the engines, which obviously come from elsewhere, Pratt & Whitney, were there. They [Pratt & Whitney] were running such high production that the parts for the engine were not going to be available for the depot,” Donald Norcross, a democratic representative from New Jersey, mentioned during last week’s hearing in exchange with Schmidt.

Efforts to expand overall F-35 production capacity have been hampered in part by the lack of a formal U.S. government decision to approve full-rate production of the jets. The F-35 JPO hopes to finally make this determination in December after a number of testing points are met. It will still then take time for any ramp-up to occur and there are also a growing number of foreign customers to support.

Depot limits

Beyond the parts themselves, there is the issue of the priority that has been given to establishing depot infrastructure to support the F-35 over the years.

“The sustainment side… requires I think a significant depot presence both in the United States and in our partner countries all around the world,” Lt. Gen. Schmidt said on Monday. “So, on that part of it, you know, I think we’re a little bit late in standing up to some of our depots to deal with the capacity that we need to get to… in this Lot 15-17 negotiation we actually held back on the urge to buy aircraft with depot stand-up money and held our own to keep that money available to stand up depots. That’s a huge win.”

Schmidt did elaborate on this apparent potential reallocation of depot-related funding to procure more F-35s, a separate production capacity issue that has become an increasingly hot topic of conversation. The War Zone has reached out to the F-35 JPO for more insight into this matter and how money that could have gone to establishing depots may have been used over the years to buy more jets instead.

At present, there are six F-35 depots within the U.S. military, but this entire enterprise is not expected to reach its full planned capacity until 2028, according to written testimony Schmidt provided ahead of the hearing before the subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee last month. The F-35 program head also disclosed that “U.S. depots are executing fifty-five percent of component repairs” when it comes to “activated workloads,” which refers to the sustainment tasks they are currently cleared to perform.

There is additional sustainment infrastructure operated by foreign partners, as well as by Lockheed Martin and its supplier base.

The global supplier base, while it certainly has benefits in terms of distributing cost burdens and other responsibilities, presents its own complexities. This was underscored when Turkey was ejected from the F-35 program, a lengthy process that started in 2019 primarily in response to operational security concerns related to that country’s purchase of Russian-made S-400 surface-to-air missile systems. The Pentagon used hundreds of millions of dollars that had been set aside to buy spare parts to help find replacements for Turkish suppliers, as you can read more about here.

A question of data rights

Even with sufficient spare parts and depot capacity, the U.S. military and foreign F-35 operators have historically been limited outright in the kinds of maintenance and supply chain activities they are allowed to do organically under contracts with Lockheed Martin. This applies to the physical aspects of the aircraft and the complex computer software that underpins its mission systems. The company has been fiercely protective of its proprietary data rights.

“Securing technical data to enable organic maintenance and repair of aircraft, assemblies, and components remains critical” to help “reduce sustainment operating costs,” Lt. Gen. Schmidt explained in the written testimony he provided ahead of the subcommittee hearing last month. “The F-35 program is currently evaluating data necessary to support organic maintenance and repair including software sustainment, and we will be utilizing the extended ordering authority to secure such data.”

Securing data rights has already added hundreds of millions of dollars to the overall F-35 program price tag.

“The government wasn’t diligent about getting the data rights it needs,” Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall had said bluntly at a roundtable on the sidelines of the annual Air & Space Forces Association Warfare Symposium in March. “I think that’s created a lot of difficulties over the past 20-odd years.”

The F-35 program has only really begun working in recent years to get more direct control over important parts of the supply chain. This includes the simple warehousing of things like spare parts and their distribution.

“The F-35 JPO continues to drive towards increased U.S. Service participation across our sustainment operations. For example, in January 2021, we established a Service Level Agreement (SLA) with the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) for North American warehousing, and with the U.S. Transportation Command (USTRANSCOM) for Global Transportation and Distribution,” Lt. Gen. Schmidt told lawmakers on the House Armed Services Committee in his written testimony last month. “DLA and USTRANSCOM are now responsible for booking and shipping functions in support of Government-owned F-35 global spares material to and from global locations as directed by the JPO. To date, we have transitioned over five thousand part numbers [types of parts] and two million parts out of Lockheed Martin warehouses and into DLA warehouses and have conducted over forty thousand CONUS [continental United States] parts shipments under the arrangement.”

Many of these issues are, of course, not necessarily unique to the F-35 program. At the same time, the specific combination of factors makes them particularly pronounced, especially given that the aircraft is a complex fifth-generation stealth fighter. Stealthy aircraft, in general, typically have higher maintenance requirements just due to their basic design features — especially their low observable skins — and construction. Newer types, like the F-35, are increasingly loaded with complicated and maintenance-intensive subsystems that are intertwined due to sensor fusion requirements.

As a result, the so-called sustainment ‘tail’ that is required to support F-35 force packages is often higher, to begin with, than it might be for a similar number of non-stealthy fighter jets.

At the F-35 panel discussion on April 3, Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Air Commodore Angus Porter, the Air and Space Attache at the country’s embassy in Washington, noted that just bringing Australian Joint Strike Fighters to this year’s Avalon Airshow had highlighted the “significant challenge” of supporting these jets on operations across extended distances. Most of Australia’s F-35s are stationed at RAAF Base Williamtown, around 550 miles northeast of the Avalon Airport, where the show is hosted. The rest of the RAAF’s Joint Strike Fighters are even further away, around 1,785 miles to the northwest at RAAF Base Tindal.

What about in a real war?

All of the aforementioned issues impact the F-35 sustainment infrastructure globally now, in a peacetime context. This comes back to questions about the resiliency of the relevant supply chains in an actual conflict, especially a potential high-end one against a near-peer competitor such as China. This goes back to Lt. Gen. Schmidt’s highlighting the concern that the current ‘just-in-time’ model could easily be at risk.

It is something of a truism that, in any high-end conflict, such as a potential one against China in the Pacific, both sides can be expected to focus heavily on neutralizing each other’s supply chains. The U.S. military, as a whole, is very concerned about the prospect of having to conduct logistics operations in heavily contested environments full of myriad existing and emerging threats. Growing vulnerabilities to traditional airlift and sealift capabilities are forcing American officials to explore a host of novel logistical concepts, including uncrewed air and sea platforms.

The ever-increasing proliferation of advanced ballistic and cruise missiles, as well as various tiers of armed drones, even by non-state actors, present particular threats to American forces on and off the battlefield, as well as to critical civilian infrastructure. The War Zone highlights these realities on a regular basis.

It is another basic fact of major wars that logistical demands and strains on supply chains simply increase dramatically even without any kind of direct enemy action. Units go through all sorts of things much faster in active high-combat scenarios than they do in peacetime. As a result, keeping up with the need for things like more spare parts, and the basic raw materials required to produce them, becomes even more challenging and in some cases impossible. Keeping the transportation infrastructure required to move all of that around, and keep it up and running, only presents another layer of complexity, especially as raw materials and other components may come from what would quickly become a combat zone.

As a general example of the immense scope and scale of combat supply requirements, at least as of 2018, the U.S. Army had concerns about large ground combat units being able to keep fighting at their highest capacity for even a week without an uninterrupted logistical chain. These issues have only been further brought to the forefront by the conflict in Ukraine.

The U.S. military, among others around the world, has taken experiences from that war to heart already and officials are reassessing long-established expectations about the logistical requirements for a major fight. The U.S. government is now working to re-invest in military-related production capacity, especially when it comes to munitions production, just in response to the demands of supporting the Ukrainian armed forces. For more than a year now, still-expanding aid transfers to Ukraine’s military have prompted questions about whether U.S. military stockpiles of key weapons and ammunition, as well as various supply chains, are robust enough for its own purposes.

The fighting in Ukraine has only underscored the complexities of ensuring unbroken supply chains for even the most basic necessities under the constant threat of enemy attack, as well.

It is worth being said that any actual conflict will come along with a greater acceptance of certain risks to help ensure operational capacity.

“We were talking about how would you work through the maintenance in an… Expeditionary Advance Base environment,” U.S. Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Michael Cederholm, the current deputy commandant for Aviation, said during the April 3 panel talk. “We started our thinking by how are we going to do the inspections we do.”

Expeditionary Advance Base Operations (EABO) is a set of new distributed concepts of operations that the Marine Corps is still in the process of refining. At its core, EABO is focused on the ability of relatively small formations of Marines being able to quickly deploy to forward locations and hold enemy forces at risk, to hopefully deter an opponent, but then also be in a better position to strike if required. Those forces, which could have significant aviation and stand-off munitions capabilities, would then be expected to have the ability to just as readily reposition as the circumstances in the battlespace change. You can read more about how Marine F-35Bs fit into this vision specifically here.

The U.S. Air Force will be presented with the same kinds of challenges when employing its F-35s in future expeditionary and distributed operations. The service is developing its own concepts of operations in this regard, referred to collectively as Agile Combat Employment (ACE).

“We’re not [going to do those inspections], we’re in combat,” Cederholm continued. “We mitigate risk all the time.”

The can-do remarks from the Marine Corps’ top aviation officer don’t change the fact that the U.S. military clearly sees serious additional risks emerging from the current supply chain concepts in place now. In addition, though efforts are already being made to address certain aspects of the larger problem, how long it might take for those changes to be felt remains to be seen. This comes as concerns are growing about the potential for a real conflict with China, possibly over Taiwan, before the end of the decade.

A different model does exist

Altogether, it is not hard at all to see how a just-in-time model is just inappropriate when it comes to supporting the F-35, and other military systems, especially in a major war. If the current supply chains are already struggling in peacetime to provide sufficient spare parts, it is difficult to see how they could possibly withstand a surge in demand driven by a large-scale conflict and the increased threats of enemy strikes on logistics nodes and the likely large-scale disruption of commercial logistics.

All that being said, there are very real hurdles that will need to be overcome before any significant changes to the sustainment backbone of the F-35 program can be made. However, there is a model that may help point the way forward, at least in part.

The Israeli Air Force is an F-35 operator, but sensed early on that the centralized support structure for the jets wouldn’t meet its needs, especially during a large-scale conflict. As such, authorities in Israel were able to negotiate a unique arrangement that has given them virtually complete independence from the rest of the program.

Today the IAF operates a subvariant of the F-35As, the F-35I Adir, which has a distinct configuration that has importantly not dependent on ALIS. On top of that, it is the only user of the F-35 to have the authority to install entire suites of additional domestically-developed software on its jets and to perform completely independent depot-level maintenance.

“The ingenious, automated ALIS system that Lockheed Martin has built will be very efficient and cost-effective,” an anonymous Israeli Air Force officer told Defense News in 2016. “But the only downfall is that it was built for countries that don’t have missiles falling on them.”

Israel has further leveraged its unique position as an F-35 operator to expand its own organic research and development and test and evaluation capacities. The country also looks to be moving toward expanding its support depot infrastructure. Yesterday, Lockheed Martin was awarded a modification to an existing contract award, worth approximately $17.8 million, specifically to “provide a depot maintenance activation plan in support of establishing initial depot capability for the F-35 air vehicle for the Government of Israel.”

Israel’s concern over the reliability of the F-35 during a time of war has likely also extended to stockpiling parts and being able to leverage its operational independence agreement to meet what it sees as its unique logistical requirements for the jet. The ISAF has a long history of doing this with variants of the F-15 Eagle.

Israel’s F-35 sustainment model may not be fully translatable to the U.S. military, which is substantially larger and has different operational demands placed on it. Still, it does offer an important example of how things might be structured differently and that it can be done. If nothing else, the drivers behind the IAF’s push for independence from the broader F-35 program all speak directly to many of the issues that Lt. Gen. Schmidt and others are just starting to raise more publicly now.

It also prompts new questions about whether these issues were downplayed for years, if not decades, due to concerns about how they might have led to near-term cost growth and otherwise impacted the future of the program. Though the F-35 program is now very well-established overall, it has faced significant justifiable criticism over the years and calls in the past for it to be massively restructured, if not abandoned entirely.

Overall, the emerging consensus within F-35 communities in the United States and abroad that just-in-time logistics will just not be sufficient in a major fight is unsurprising. Unfortunately, it is still to be seen how quickly and effectively the Joint Strike Fighter program can overhaul its supply chains to be more resistant to any future “hiccups,” ones that will likely come en masse at the worst possible time.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com