Former U.S. Navy Super Hornet pilot Roderick “Hot Rod” Kurtz was surprised.

On a fair-weather summer afternoon in August 2017, just under two years after he retired from active duty flying F/A-18E/F Super Hornets with Strike Fighter Squadron 122 (VFA-122), the “Flying Eagles,” Kurtz was airborne in a Hawker Hunter acting as an adversary to help train the Navy fighter pilots and ship crews he’d only recently parted company with.

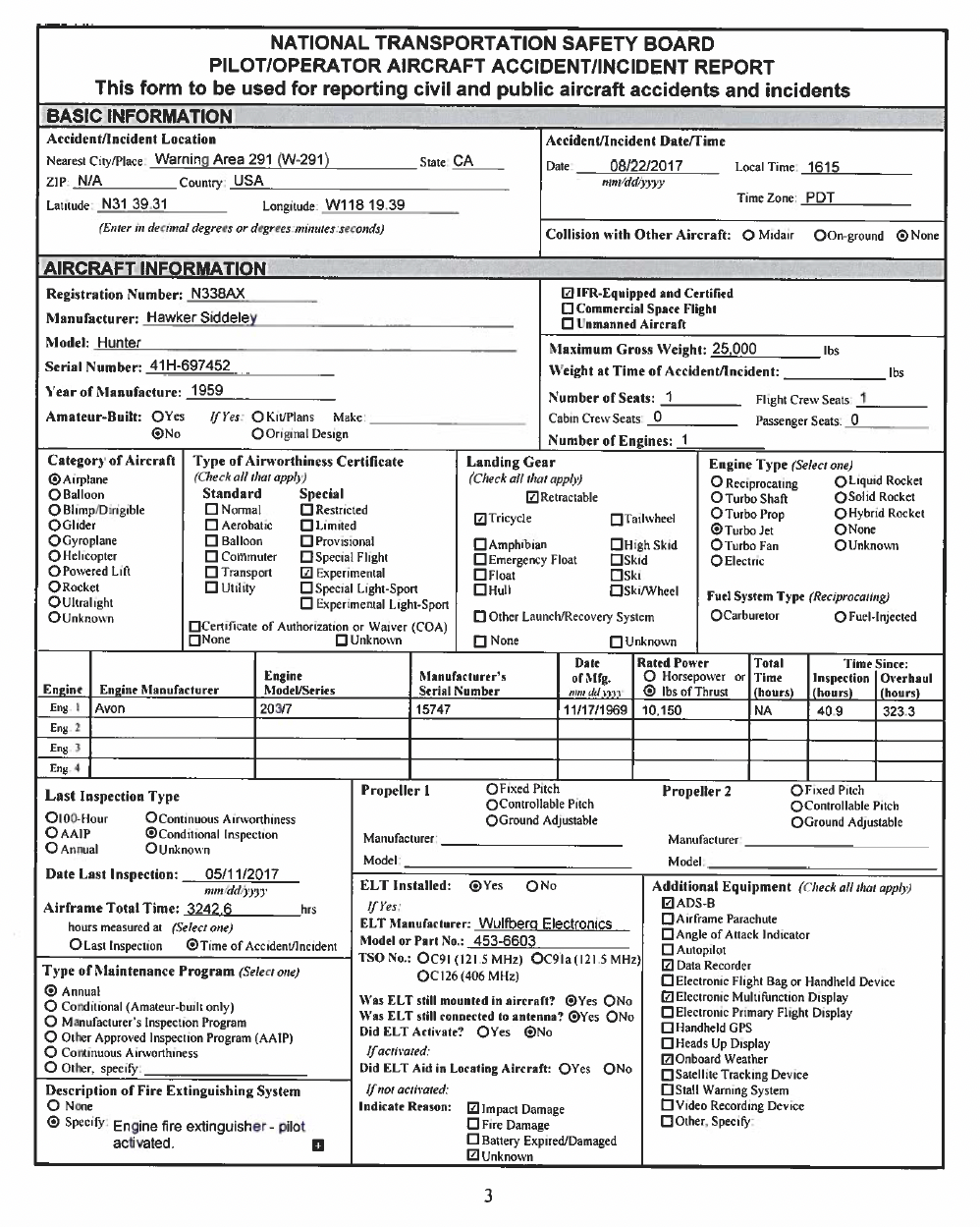

The single-seat Hunter Mk 58 Kurtz was strapped into was originally manufactured in 1959, part of an original batch of 100 Hunters that served with the Swiss Air Force until 1994. By 2017, it was part of the Airborne Tactical Advantage Company‘s (ATAC) stable of Hunters used to fulfill a variety of red air roles on a Navy adversary contract.

Fifteen thousand feet above the Pacific, roughly 80 miles southwest of San Diego, Kurtz was wingman in a two-ship Hunter formation led by fellow ex-naval aviator and ATAC Vice President of Business Operations Richard “Miggs” Zins. It was about 4:00 P.M. when an F-35A stealth jet from the 62nd Fighter Squadron at Luke Air Force Base, Arizona, joined Kurtz’ Hunter, just 500 feet off his right wing.

“It wasn’t what you’d do if you were intercepting and escorting an enemy aircraft. I made a call to Miggs saying, ‘I don’t know what he’s doing.’” Kurtz recalls.

Moments later, Kurtz heard the F-35’s Navy controller tell its pilot and his flight lead to drop their escort of the Hunters. That’s when the fighter on Kurtz’ right wing did something he didn’t expect.

“Instead of being tactical and dropping behind and below and leaving, or just giving a friendly wave then peeling off, he accelerated and pulled in front of me from the right-hand side, crossing my nose very hard from right to left, probably just 300 to 400 yards ahead. I could see the full planform of the F-35, the top of the jet.”

Kurtz called his Navy red air controller immediately.

“‘I don’t know what he’s doing but he just pulled out in front of me and crossed my nose!’”

“I can tell my controller is confused too. He says, ‘That’s weird.’ And he says, ‘If he’s going to fly out in front of you, go ahead and follow him.’”

Naval Air Station Point Mugu, 3:17 P.M., August 22, 2017

It was week three of a Composite Training Unit Exercise (COMPTUEX), a Navy training period during which all elements of a Carrier Strike Group — ships plus air wing — come together to prepare for deployment. Carrier Strike Group Nine (CSG-9), including the Nimitz class carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt with Carrier Air Wing 17 aboard was 100 miles off the coast of southern California in the last phases of the exercise.

Kurtz and Zins, using callsigns “JEST 11” and “JEST 12,” were playing the role of ‘bad guys’ from a hostile fictional country, probing the strike group’s defenses, complicating the air defense picture for the Roosevelt and the guided-missile cruisers and destroyers escorting it, as well as the carrier’s air wing.

The air wing’s blue air role was to “intercept, identify and escort” any red air aircraft that snuck up on the carrier. “They have alert aircraft airborne to protect the ship from an unknown threat that we represent and vector F/A-18s to intercept us and identify us visually,” Kurtz explains. “They look to see whether we’re carrying arms or bombs.”

Kurtz knows F/A-18s well. His career began in the F/A-18C, flying with VFA-113 on two deployments including a combat tour during Operation Iraqi Freedom. The rest of his flying was done from just one air station, Naval Air Station Lemoore near Fresno, California. Home to Strike Fighter Wing Pacific’s five air wings, Lemoore is where Kurtz was an instructor in the Hornet and Super Hornet until he left the Navy in November 2015.

He soon went to work for ATAC and gained a type rating in the Hunter the following winter. By April 2016, he was back at Lemoore, flying against the squadron he last served in, VFA-122.

ATAC has flown the British fighters, first fielded by the U.K. Royal Air Force in 1954, since 2003, providing training for generations of naval aviators. But before joining the adversary air firm, Kurtz had never seen a Hunter, let alone flown one. He describes transitioning to the 1950s-era jet fighter from the Super Hornet as a refreshing change from managing sensors, radars, datalinks, and students.

“It’s not necessarily the easiest plane to fly,” Kurtz says of the Hunter. “There are no autopilot features, no head-up display. It’s stick-and-throttle flying the whole time. But that was fun!”

Fun wasn’t the focus as Hot Rod and Miggs briefed with their red air controller, a former squadron mate of Kurtz’ and a close friend.

“We’re all carrying TCTS [Tactical Combat Training System] pods. Our radar links and communications are presented to the controllers so they can see and understand the airspace and direct us,” he explains. “The controller briefs us, ‘Here’s where I want you to show up. Here’s about where the ship is. Call me on this frequency when you get out there.’”

The two Hunters left the runway at Point Mugu and made a 15-minute transit flying above a low, broken cloud layer to their assigned on-station position and altitude block between 10,000 and 14,000 feet northeast of CSG-9.

Once on station, JEST 11 and 12 began executing their role in the exercise following guidance from the red air controller who steered them toward the carrier to test its defenses — then steered them away from the ship to see if they could lure Roosevelt’s fighters away.

“We spent about a half-hour getting close to being intercepted,” Kurtz says.

CVW-17 Super Hornets shadowed the Hunters for a period until they were relieved by two 62nd Fighter Squadron F-35As. Kurtz had read that the stealth fighters would be part of the COMPTUEX in the exercise instructions but notes that it was very unusual for Air Force fighters to participate in this Navy training and had no idea why they were a part of the event.

“Mixing an Air Force group in isn’t something the exercise operators would really have been interested in usually. I just assumed that since the F-35 was fairly new (the F-35 had only been operational for a year with the USAF), people that had them needed to fly. Anything they could participate in to get experience was valuable, I guess.”

3:30 P.M., at 15,800 feet, north of CSG-9

At the direction of CSG-9 controllers, the F-35s were vectored from their combat air patrol station south of the strike group to intercept and escort the ATAC Hunters.

“When they showed up, I remember it being a point of interest, having not seen an F-35 fly before,” Kurtz says. “I wasn’t shocked. But I was still curious as to why they were participating.”

Kurtz and Zins were flying in a spread formation about a mile apart with Zins trailing slightly behind and to the right when the F-35s joined on them.

“The guy on my wing joined in a very close position, more familiar and less combat/tactical,” Kurtz explains. “It wasn’t what you’d do if you were intercepting and escorting an enemy aircraft. It was more like what you’d do if you were on week three of a COMPTUEX and bored of intercepts.”

The F-35s held formation with the Hunters for about 15 minutes. As the British-made fighters flew northward away from the carrier strike group, Kurtz remembers when “on the common frequency, I hear their controller tell them to drop the intercept and return to their CAP station.”

Kurtz expected the F-35s to depart in the manner he outlined “but none of the above happened.”

ATAC Hunters operating out of Naval Air Station Point Mugu:

Cleared by his controller to follow the F-35 that had flashed across his nose from right to left, Kurtz initially banked to the left. But the F-35 pilot “immediately reversed and comes back left to right!”

Just 800 feet in front of the Hunter, the maneuver reminded Kurtz of the ‘level weaves’ Navy fighter pilots often do to warm up prior to dogfighting and practice gun drills.

“I’m thinking I’m going to hit his jet wash,” Kurtz says.

To minimize the effect of turbulence from the F-35, Kurtz released the Hunter’s controls to unload the jet and fly through any wash wings-level. “I hit the thump pretty good. It felt like an F/A-18’s jet wash which is stiff and concerning.”

But everything “seemed fine.” With the F-35 now off to his right, Kurtz pulled his stick to the right to get about 60 degrees of bank angle and applied back-stick to keep the Hunter’s nose up.

“As soon as I’ve done that the plane departs to the left and does two rolls all the way around!”

Out of habit, Kurtz released the flight controls again. “It felt like maybe I induced the departure when I applied G. So I backed off the G and thought, ‘If the wings don’t stop, at least level them from the roll.’”

The airplane stabilized and Kurtz regained control. But he was descending, “15 to 20 degrees nose-low” and worried about busting through the lower end of his assigned altitude block. So he pulled back on the stick.

“As I start to pick the nose up it immediately departs again. Same thing, it rolls a couple times to the left — this time from wings-level. I’m not in a right bank anymore.”

“As I’m trying to stop the left roll, I can feel that the stick will not go past the right of center. Now I know there’s something in the flight controls that’s jammed. That’s when I made the ‘I’m out of control!’ call to my wingman.”

But Kurtz regained control briefly. Leveling his wings in an even steeper 30- to 40-degree dive, he resisted the urge to try to raise the nose again, knowing that’s what caused the Hunter to depart seconds before. Quickly, he tried to assess whether the antique British fighter’s hydraulically boosted flight controls were still being boosted.

Head-down in the cockpit, Kurtz looked for the white/black magnetic indicator on the instrument panel that indicates whether the hydraulic boost is on or off. The indicator looked to be white, affirming that the boost was on.

“But there’s sunlight coming into the cockpit and the glare makes me think, ‘maybe it just looks white.’”, Kurtz recalls.

Immediately he flipped the boost-control switch, watched the indicator go black, turning boost off, then flipped it on again and saw the indicator show white as it should. He had just completed that bit of troubleshooting when he looked out of the cockpit and saw the marine layer.

“I look at the altimeter needles and they’re winding down through 4,000 feet fast!”

4:16 P.M., at 4,000 feet, south of CSG-9

“I thought, ‘Find the ejection handle!’”

With JEST 11 accelerating through 400 knots, Kurtz felt for the handle down between his knees. Mounted much lower and with a different shape than the Hornet/Super Hornet ejection handles he was accustomed to, Kurtz struggled, worried that he wouldn’t find the small hand grip.

But he got a hold of the handle, lifted his head, and pushed his shoulders back against the Hunter’s Martin-Baker Mk 3 ejection seat to be in the best posture for ‘banging-out,’ hoping the seat — generations older than the Super Hornet’s Mk 15 to Mk 17 equivalent — would operate properly.

“I made the call to Miggs, ‘I’m ejecting!’”

Zins followed the path of Kurtz’ Hunter, keeping his eyes glued to the airplane.

“I pulled the handle, and the canopy went immediately into the wind stream and was ripped off by the air loads. About a half second later the seat went.”

“It’s a good hit and makes you grunt but it worked! I tumbled around a bit and then the chute opened. I was a little disoriented, but the chute-opening shock was actually stiffer than the ejection seat shock. At 450 knots that makes sense.”

The seat’s chute opened immediately due to the low altitude, Kurtz says. Dropping through the clouds of the marine layer, he remembers just one thing — seeing his jet hit the water.

“The airplane went into the water and instantly became a white froth on the surface.”

With the ocean rushing up at him, Kurtz didn’t have much time to think, his only notions being to prepare for hitting the water and focus on getting out of his parachute. Super Hornet parachutes have a saltwater-activated release system, but he would have to manually escape the Hunter’s chute.

“Hitting the water wasn’t overly dramatic,” Kurtz says. “I shot eight or 10 feet down and popped back up to the surface then tried to hit the three release points on the harness. I had my hands on two of them then had to find the third. But I found it, rolled out of the chute, and felt pretty good.”

Designed to inflate on contact with salt water, Kurtz’ automatic inflation vest remained limp until he scooped seawater to its sensors, triggering inflation.

“I remember looking up at the sky after figuring out I wasn’t going to drown and thinking, ‘We have plenty of daylight left.’”

“Every little step of success made me feel better. One lucky thing was that the water was calm, no whitecaps, and the marine layer had kind of broken up somewhat. Miggs knew that I had ejected but he couldn’t see my chute. He saw the airplane go in and the big oil slick it left because the sea state was calm and assumed I was near that slick.”

4:30 P.M., floating in the Pacific

Once Kurtz was floating, he pulled out his PRC-90, a waterproof emergency rescue radio that has been part of naval aviators’ survival gear for decades. To hear it, he had to remove his helmet.

“There goes the one white reflective spot on my body,” Kurtz quips.

He radioed Zins, orbiting above, to let him know he had survived and was okay. Zins acknowledged the call but his reply and all those that Kurtz received thereafter were garbled.

Fifteen minutes passed before Zins, low on fuel, was relieved by Super Hornets from the Roosevelt.

“I call them a couple of times and I hear them respond,” Kurtz explains. “I don’t know what they’re saying but they’re right overhead. I assumed the entire time that people see me. It turns out they didn’t. They just saw the oil slick. Fortunately, I wasn’t far away.”

Meanwhile, a smaller drama was playing out near the Roosevelt. An MH-60S from Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron 6 (HSC-6) was airborne near the carrier fulfilling its role as a plane-guard helicopter, available at a moment’s notice to rescue naval aviators if there’s an accident aboard the ship or nearby.

The HSC-6 crew, including a newly certified aircraft commander and an experienced copilot, were in the final moments of their shift and low on fuel when the emergency search and rescue (SAR) call for Kurtz arrived. The crew had to refocus quickly, all while waiting for the carrier to decide whether to recover and refuel them or just vector them to the Hunter’s accident site.

After about 30 minutes in the water, Kurtz spotted the MH-60. The HSC-6 crew didn’t know Kurtz’ exact position because the civilian emergency GPS transmitter he had was only able to broadcast one good fix before faltering.

“They’re not quite on top of me but I get them on the radio and say, ‘Hey I’m at your 3 o’clock!’”

The helicopter turned toward Kurtz but didn’t come directly for him until he unlimbered an emergency flare and fired it.

“Again, I assume they see me,” Kurtz recalls. “Waiting for the helicopter to go that last mile to me felt like the longest period of waiting in the whole episode.”

The MH-60’s crew chief was the only crewmember to see where Kurtz’ flare had originated from. Even with that cue, it wasn’t until Kurtz wearily splashed water with tired arms that the crew physically spotted him.

With the MH-60 overhead, powerful rotor wash whipped the sea around Kurtz who turned his back to the helo to shield his eyes. “It was actually painful, and it was hard to stay in any position when you’re just bobbing in the water and you’re not in a raft.”

A rescue swimmer dropped into the water and spent 20 minutes securing Kurtz to a backboard to be hoisted up to the MH-60.

“I was feeling okay initially but as time went on I was getting a little cold, sore, and achy in places. Because I was wearing a flotation device around my shoulders and hanging in the water there was zero pressure on my back so that wasn’t a concern at the time.”

Kurtz praised the MH-60 crew but notes that being secured to the backboard was nerve-wracking as waves splashed over him while his limbs were lashed down, precluding any option to swim.

Once aboard the helicopter and having assured the crew that he was generally in good condition, Kurtz was a passenger. The MH-60S made a 15-minute transit to the cruiser USS Bunker Hill, part of CSG-9, to suck up some urgently needed fuel and take a corpsman aboard. From there, it was a 40-minute trip to San Diego and Balboa Naval Hospital.

A lucky day

By the time Kurtz reached the medical center his adrenalin had worn off, he was tired and feeling pain in his back. Examinations revealed compression fractures to three of his vertebrae due to the ejection.

Now a first officer flying Boeing 737s with Southwest Airlines, Kurtz looks back on the accident with several lingering questions. Until we inquired, neither the Navy nor Air Force had commented on the incident though both acknowledge that they were “aware of the event.”

Naval Safety Command and the Air Force Safety Center provided coordinated responses saying, “the event was not reportable” in Naval channels or U.S. Air Force channels “as no damage or injury occurred to personnel or assets, and the lost [Hunter] Mk 58 was flown under a Navy contract.”

The services explain that they “investigate contractor events in which there is reported damage to DoD property or injury or occupational illness to DoD personnel” or when “damage to public or private property, or injury, or illness occurs to non-DoD personnel.”

Because no injury to DoD personnel or the public occurred and because there was no damage to DoD or public property, the services were only obliged to assist the National Transportation Safety Board’s investigation — the only examination of the incident — in ‘party to’ status.

The responses don’t address questions including who was actually flying the 62nd Fighter Squadron F-35s that day.

The 56th Operational Group oversees the entire fighter-training mission at Luke Air Force Base. According to the group’s official 62nd Fighter Squadron web page, the squadron “trains F-35A Lightning II fighter pilots as a joint international effort between Italy, Norway, and the United States. Italian, Norwegian, and American pilots will fly Italian, Norwegian and American F-35s under the guidance of American instructor pilots.”

Kurtz wonders if the pilot who rocketed past his nose was perhaps Norwegian or Italian. For now, there’s no indication that they were or were not foreign flyers. Either way, Kurtz considers that dramatic Tuesday a lucky day.

“Most of the things that had to go well did,” he reflects. “If it’s nighttime when I eject, if it’s winter, if my seat doesn’t work right, my parachute, if there’s not a helicopter on station… I tend to look back on it as a day where I got really lucky.”

Contact the editor: tyler@thedrive.com