The U.S. Air Force is planning to retire its remaining RQ-4 Global Hawk high-altitude, long-endurance drones by the end of the 2027 Fiscal Year. The service says it has become clear that the RQ-4s would be overly vulnerable in any future conflict against a peer or near-peer adversary, but it’s not clear what aircraft (or other assets) might fill the resulting capability gap. This only adds to the growing evidence that a top-secret, high-flying, stealth spy drone, commonly referred to as the RQ-180, or variants or derivatives thereof, is getting close to entering service, if it isn’t already being employed operationally on some level.

Breaking Defense was the first to report on the Air Force’s plans to sunset the last of its Global Hawks in the next five years after obtaining a letter sent from the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC) to Northrop Grumman, the manufacturer of the drones. The service subsequently confirmed that the goal is to have this divestment process completed no later than the conclusion of the 2027 fiscal cycle, which ends on Sept. 30 of that year. This would include the retirement of the Air Force’s nine Block 40 variants, which are the most modern versions of the Global Hawk it has in its inventory now.

“Our ability to win future high-end conflicts requires accelerating investment in connected, survivable platforms and accepting short-term risks by divesting legacy ISR [intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance] assets that offer limited capability against peer and near-peer threats,” Ann Stefanek, an Air Force spokesperson, told Breaking Defense.

The Air Force began operating its first Block 40 Global Hawks, the newest generation of the RQ-4 drone, in 2013. These unmanned aircraft, which can fly at altitudes of up to 60,000 feet on missions lasting 34 hours or more, are equipped with an advanced active electronically-scanned array (AESA) radar with synthetic aperture imaging and ground moving target indicator (GMTI) functionality. Previous versions of this drone were fitted with other sensor combinations.

It’s not necessarily surprising that the Air Force is looking to stop operating the Global Hawk entirely. The service has been pushing to get rid of more and more of its Global Hawks for years now and has been increasingly successful on that front. It is currently in the process of divesting its older Block 30 RQ-4s, with the last of those expected to be retired by the end of 2023.

The Air Force has already removed all of its Block 10 and Block 20 Global Hawks from service, including a trio of Block 20 EQ-4B variants equipped with the Battlefield Airborne Communications Node (BACN) communications gateway payloads. Some ex-Air Force Block 20 Global Hawks are now in the process of being turned into test assets to support the development of hypersonic weapons.

In addition, three modified Block 10 RQ-4s returned to the United States in June, having been operated by the U.S. Navy for 13 years from Al Dhafra Air Base in the United Arab Emirates under the Broad Area Maritime Surveillance Demonstrator (BAMS-D) program. The BAMS-D drones now appear to be slated for retirement. The Navy will still continue to operate MQ-4C Tritons, which are maritime patrol-optimized Global Hawk derivatives.

Beyond this dwindling operator base within the U.S. military, Iran shooting down the fourth BAMS-D drone over the Persian Gulf in 2019 sparked a very public discussion about the utility of the Global Hawk family in future higher-end conflicts against opponents with more robust air defense networks. The statement that Breaking Defense received from Air Force spokesperson Stefanek cites exactly these issues in explaining the reasoning behind the Air Force’s decision to stop flying these drones altogether within the next five years.

The Air Force has been more or less making this specific argument for closing the book on its Global Hawk fleet, as well as other “legacy ISR platforms,” for more than a year now.

“Legacy ISR platforms, once considered irreplaceable to operations, are often unable to survive or deliver needed capabilities on competition-relevant timelines,” written remarks that Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown submitted ahead of a Congressional hearing in May 2021. “These legacy platforms must be phased out, with resources used to invest in modern and relevant systems. Working together, we must take [a] calculated risk now in order to reduce the greater future risk.”

“For instance, the RQ-4 Block 30 Global Hawk was crucial to the ISR requirements of yesterday and today. However, this platform cannot compete in a contested environment,” that statement added. “The Air Force will continue to pursue … RQ-4 Block 30 divestment … in order to repurpose the RQ-4 Block 30 funds for penetrating ISR capability. Overall, intelligence collection will transition to a family of systems that includes non-traditional assets, sensors in all domains, commercial platforms, and a hybrid force of 5th- and 6th-generation capabilities.”

“The Block 40s will be very critical in the next six, seven, eight years, while we go to the ‘what next,'” Air Force Lt. Gen. David S. Nahom, the service’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Programs, told lawmakers at a separate hearing in July 2021, according to Air Force Magazine. “[The Air Force is] bringing on … a family of systems … [and] I’ll have to come back in classified session to talk about that more.”

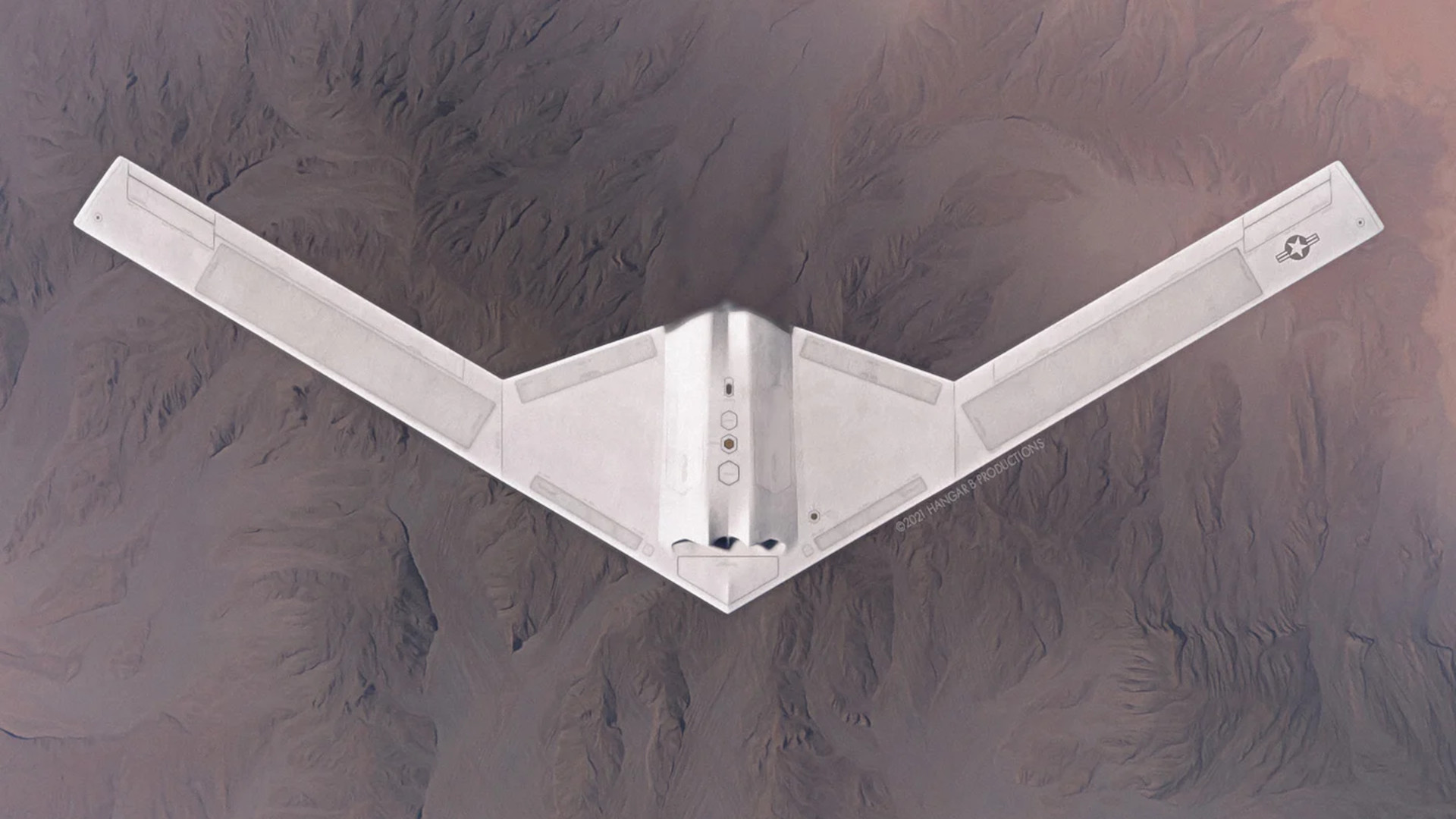

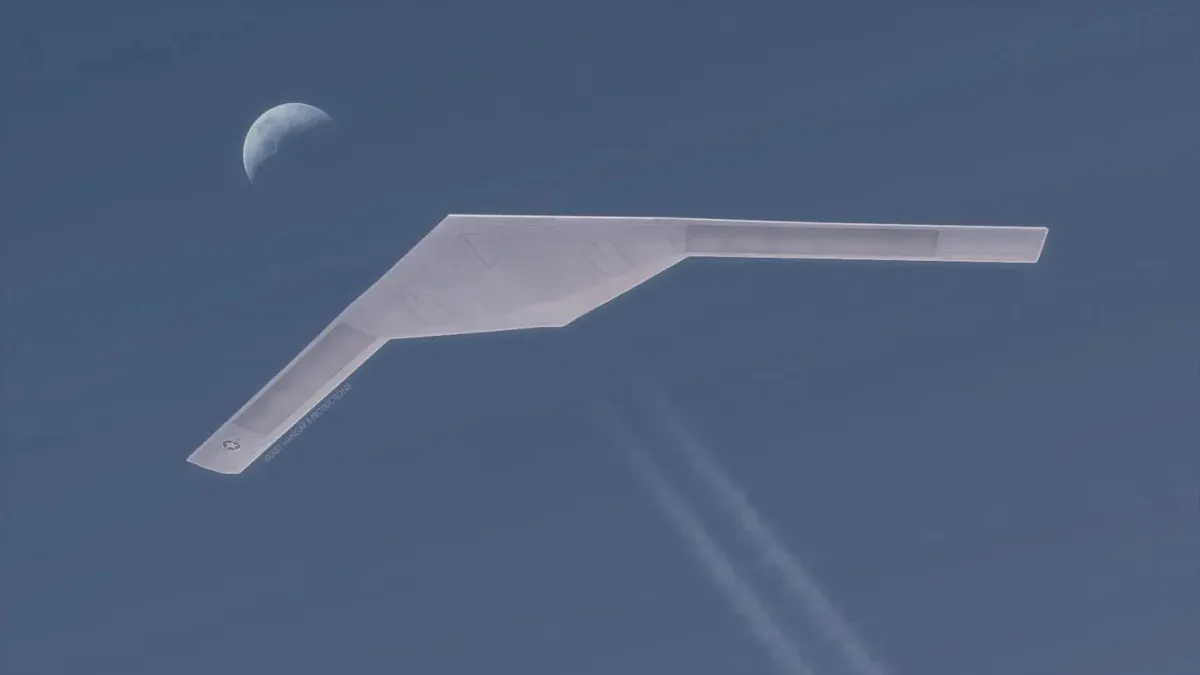

As The War Zone reported following Gen. Brown’s remarks, there is significant evidence that the specific mention of a “penetrating ISR capability” refers, at least in part, to a top-secret and very stealthy spy drone commonly referred to as the RQ-180. Nahom’s comments, which implied the impending retirement of the Block 40 Global Hawks between 2027 and 2029, further point to this advanced unmanned aircraft waiting in the wings.

There have already been steadily growing indications in recent years that the RQ-180, which could also serve as a communications and data-sharing node, is moving closer to entering operational service, if it hasn’t already on some level. Of course, other advanced stealthy designs could be included in this category, as well, including smaller, tactical drones used for distributed intel collection operations. Still, the RQ-180, or a version of it, could be key in enabling those aircraft, as well.

Of course, as Gen. Brown made clear at the hearing last year, aircraft of any kind will only be one part of the future ISR equation. New spaced-based systems will also form an important part of the intelligence-gathering ecosystem within the Department of the Air Force, which now includes the U.S. Space Force.

In 2021, Chief of Space Operations Gen. Jay Raymond, the Space Force’s top officer, disclosed the existence of a previously classified effort to develop new satellites carrying sensors with GMTI functionality, which would be in line with the mention of “sensors in all domains” in Brown’s statement. Just last week, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall also said in an interview with Aviation Week that the Air Force was collaborating with the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) on space-based GMTI capabilities.

The Air Force, and now the Space Force, have been increasingly looking into commercial avenues, as Gen. Brown had mentioned last year, as well. This could go beyond simply buying satellite imagery from commercial providers to actually putting ISR payloads on commercial satellites.

“Maybe there’s an in-between between building it ourselves and then taking care of the whole constellation,” Space Force Col. Dennis Birchenough, the Senior Materiel Leader at Space System Command’s (SSC) Environmental and Tactical Surveillance Acquisition Delta, said at a conference earlier this month, according to Breaking Defense. “Maybe there’s a hosted payload piece in between, because many of those satellites that they’re putting up have a lot of extra space available, a lot of size or electricity and power available.”

“So, we are definitely thinking of … providing sensors, or being a matchmaker between two companies, one that might have a sensor and one that might have some space available and pair them up,” he added. “And then we get to leverage the data link.”

It’s reasonable to expect that the Air Force will elaborate more on exactly what combination of capabilities it expects to take the place of its last RQ-4s sooner rather than later. Congress has formally blocked the service from divesting certain portions of the Global Hawk fleet, among other aircraft, in the past and legislators might seek to halt these new plans if they feel the logic behind them is lacking.

How all of this might impact, or already reflect, the Air Force’s future planning with regards to the venerable U-2S Dragon Lady spy plane remains to be seen. The possible fates of the Global Hawk and the U-2 have often been intertwined in recent years. At the same time, the Air Force has actively been exploring the ability of the high-flying U-2s to serve in other roles, especially as communications and data-sharing gateways.

What is clear is that the Air Force has determined that Global Hawk does not fit into its vision of what its ISR capabilities will look like by the end of the decade.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com