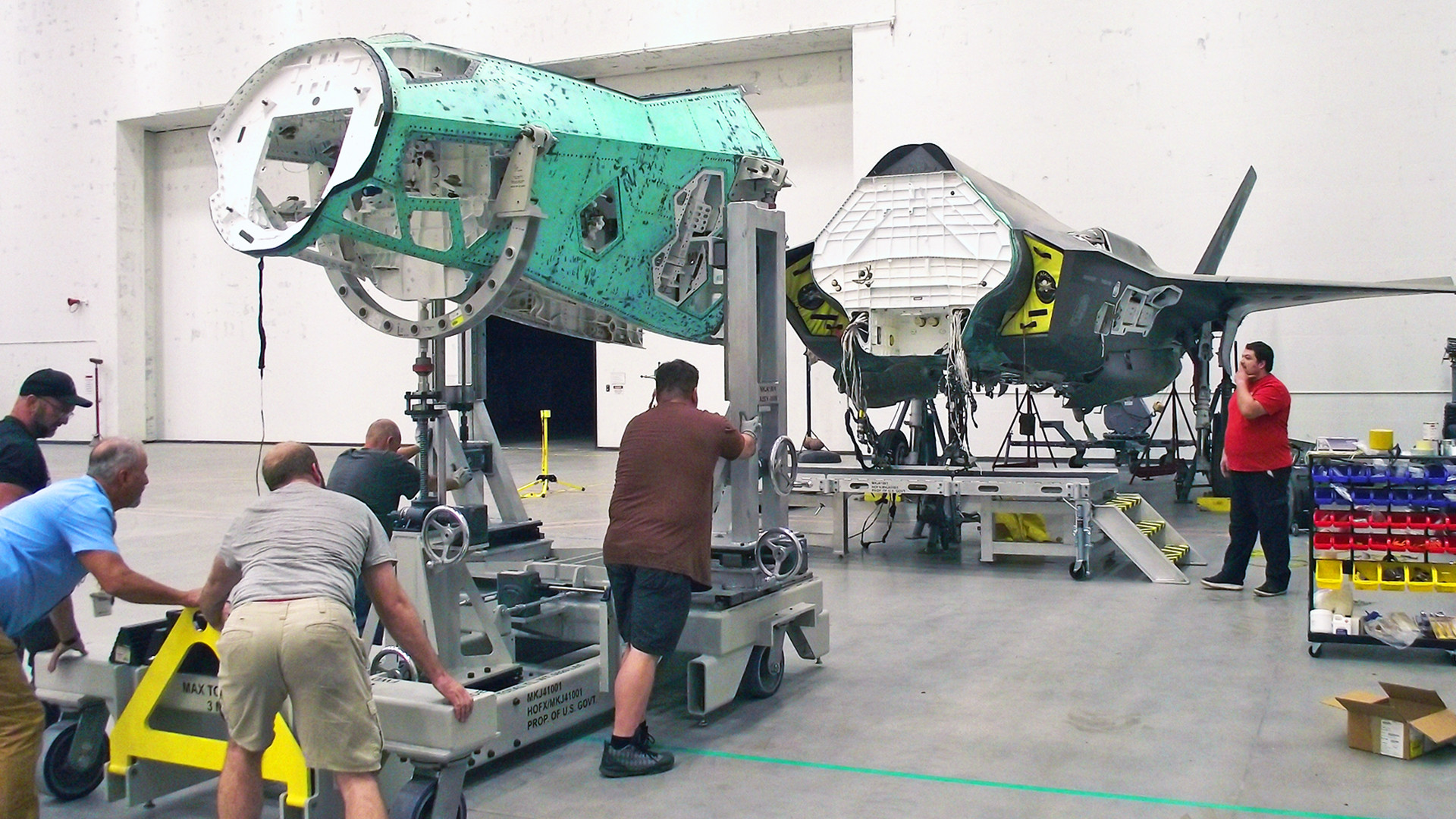

Large sections of two U.S. Air Force F-35A Joint Strike Fighters that were seriously damaged in separate accidents years ago are being grafted together into a single fully operational jet. The hope is that the process of creating this aircraft, which has been nicknamed the “Franken-bird,” will demonstrate new equipment and procedures and help improve and expand the U.S. military’s capacity to repair or repurpose severely damaged F-35s in the future.

The Franken-bird is being assembled at the Ogden Air Logistics Complex (OALC) at Hill Air Force Base in Utah. The F-35 Joint Project Office (JPO) is leading the project in cooperation with multiple units within the OALC, as well as Hill’s resident 388th Fighter Wing and the Joint Strike Fighter’s manufacturer Lockheed Martin. The 388th is one of the Air Force’s main F-35 units.

“This is a first for the F-35 program and a very exciting project,” Dan Santos, F-35 JPO’s heavy maintenance manager, said in a statement in an official release the Air Force put out about the Franken-bird project yesterday.

The Air Force release identifies the two donor airframes by their production numbers, AF-27 and AF-211. These aircraft are also known by their Air Force serial numbers, 10-5015 and 17-5269.

AF-27 suffered a catastrophic engine fire at Eglin Air Force Base in 2014 that destroyed the rear two-thirds of the jet. The pilot was able to escape the burning F-35A unharmed. Air Force investigators subsequently assessed the dollar value of the damage to the aircraft to have been in excess of $50 million. Portions of AF-27 were subsequently refurbished to the point where they could be used as an Air Battle Damage and Repair (ABDR) trainer for maintainers at Hill.

In June 2020, AF-211 lost its nose landing gear while landing at Hill after a routine training sortie. The Air Force said at the time that “the pilot egressed the aircraft and is undergoing a routine medical evaluation.” To date, an official report on the exact circumstances surrounding that incident does not appear to have been publicly released.

The War Zone has reached out to the F-35 JPO for more information about the June 2020 mishap and additional details about the Franken-bird effort.

Though the full extent of the damage to AF-211 remains unclear, the project underway now certainly points to it having been severe. The two main elements of the Franken-bird being built now include the rear two-thirds of AF-211’s airframe and the nose section from AF-27, which was left largely unscathed by the 2014 fire.

“All of the [F-35] aircraft sections can be de-mated and re-mated theoretically, but it’s just never been done before,” Scott Taylor, a lead mechanical engineer with Lockheed Martin involved in the project, said in a statement. “This is the first F-35 ‘Frankin-bird’ to date.”

Studies into the feasibility of combining elements of more than one damaged F-35 airframe to form a complete aircraft actually began in January 2020 before AF-211’s nose gear mishap. “The F-35 JPO reached out to us because we had already accomplished the really big damage restoration projects for the F-22,” Lockheed Martin’s Taylor said.

Just in April, one of the Air Force’s F-22 Raptor stealth fighters returned to the skies for the first time since it made a belly landing at Naval Air Station Fallon in Nevada back in 2018. Another F-22 suffered a similar mishap at Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida in 2012 and subsequently returned to service.

The Air Force says the Franken-bird project also leverages experience garnered from other past F-35-related maintenance efforts. This includes the establishment of a first-of-its-kind F-35 maintainer training facility at Hill using salvaged components and the partial restoration of another damaged Strike Fighter for use as an ABDR trainer last year.

“However, unlike previous projects, …. this initiative stands out due to its meticulous documentation, which will be used to establish standardized F-35 procedures that can be seamlessly integrated into routine operations in the future,” according to the Air Force. “To complete the work on site at Hill, entirely new, unique specialized tooling, fixtures, and equipment have been designed and built.”

Major repairs to any modern military aircraft can be a complex proposition. Potential issues are even more pronounced when it comes to stealthy designs like the F-35. Stealth aircraft are built to especially high tolerances and require many components, even things as small as individual fasteners, to be made and installed with equally high degrees of precision.

Deliveries of new Joint Strike Fighters have been paused in the past over things as seemingly minor as holes being drilled to the wrong specifications. Especially when it comes to the radar-evading skins on aircraft like the F-35, gaps and seams are not just unsightly, they can have seriously negative impacts on the jet’s stealthy capabilities. Linking up two large sections from separate F-35s into a single is not as easy as just bolting them together.

“We are doing this for the first time, and organizationally for the future, we are creating a process we can move forward with,” Dave Myers, the F-35 JPO Lightning Support Team lead engineer, said about the Franken-bird effort.

“Not only will this project return a combat asset back to the warfighter, but it opens the door for repairing future mishap aircraft using tooling, equipment, techniques, and knowledge that has been developed,” Santos, the F-35 JPO’s heavy maintenance manager, added.

As part of the process of fusing AF-27 and AF-211 together, there has been an effort to try to make the required equipment to perform this kind of work more deployable. “We’ve designed versatile tooling that fits neatly into a Conex box [shipping container], making it transportable to various locations, including forward operation areas,” according to Lockheed Martin’s Taylor.

It is worth noting that this is not the first time the U.S. military has grafted together existing aircraft to form new ones for various reasons. In the late 2000s and early 2010s, the U.S. Navy received three two-seat F-5F “Franken-Tiger” adversary jets that Northrop Grumman created by combining parts from F-5Fs the service had on hand with components from ex-Swiss Air Force single-seat F-5Es.

Examples of stitching portions of one complex weapon system onto another go beyond aircraft, as well. After the Navy’s Los Angeles class attack submarine USS San Francisco ran into an underwater seamount in 2005, it was eventually returned to service as something of a “franken-boat” with a ‘new’ bow section taken from the decommissioned USS Honolulu, as you can read more about here.

Foreign militaries have conducted similar repair efforts, too. The Finnish Air Force for a time had a two-seat “Franken Hornet” that had been created by blending sections from a badly damaged single-seat F-18C with ones from an ex-Royal Canadian Air Force two-seat CF-18B. That aircraft was destroyed for good in a crash in 2010.

Earlier this year, the French Navy’s Rubis class nuclear-powered attack submarine Perle finally returned to service after undergoing its own process of becoming a ‘franken-submarine’ following a devastating fire in 2020.

Still, the full extent of the benefits that may come from the proof-of-concept F-35A Franken-bird repair effort remains to be seen. It’s also not clear how feasible it would really be to do this level of work at forward locations in the field. Stealth aircraft have historically required significant logistical and sustainment footprints due to the aforementioned nature of their construction.

The U.S. Air Force is certainly very interested in expanding its ability to conduct distributed and expeditionary operations, including from remote or austere sites, which the service currently refers to as Agile Combat Employment. The U.S. Marine Corps has been refining similar concepts of operations for its forces, including its F-35B squadrons. The U.S. military, as a whole, has become increasingly concerned about the vulnerability of large established bases, especially in any future high-end conflict against a near-peer opponent, such as China. Distributed operations conducted in irregular manners are being viewed as ever-more critical to ensuring the survival of friendly forces and complicating enemy targeting cycles.

There are also time and cost questions. It is unclear exactly when work actually started to create this ‘new-ish’ F-35A, but the Air Force has made clear that doesn’t expect the jet to be ready until March of 2025. This is also said to be months ahead of the original schedule.

This is in line with how long it has taken severely damaged F-22s to get flying again. It took nearly seven years for the Raptor that ended up on its belly at Tyndall to return to service and the one that went skidding down the runway at Fallon took some five years to get back in the air.

The cost to repair the Raptor that was damaged in 2012 was pegged at approximately $35 million. How much it has taken to make the other F-22 operational again is unclear.

Of course, the F-22 has long been out of production and only a small number of these stealth fighters were ever produced, which significantly complicates even basic maintenance. Even if it costs $35 million to get the Franken-bird back in the air, that is less than the total value of the damage to AF-27. It is also less than half the price of buying a new F-35A, which is currently around $80 million based on publicly available data.

Improved and expanded procedures to repair or repurpose damaged F-35s could also just be valuable in the context of the broader challenges of sustaining U.S. Joint Strike Fighter fleets. Earlier this year, The War Zone published a deep dive into how F-35 spare part shortages and adjacent factors have created a situation that could dangerously hamper the ability of these aircraft to conduct sustained combat operations in any future large-scale fight.

In September, Lockheed Martin disclosed that plans to implement a new performance-based logistics model to try to help mitigate some of these issues had slipped into 2024. The goal had been to finalize a contract with the U.S. military in this regard before the end of the year.

When it comes to the Franken-bird, going through the process at all points to how valuable each F-35 is and that the idea of combining two damaged examples to create an operational one has relevance. Case in point, the stitched-together aircraft that will be giving a second life of sorts to both AF-27 and AF-211.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com