We’re fascinated with pirates. To say they have a peculiar allure would be a great understatement. But over time, layers of fictionalized accounts from books to movie franchises have drastically blurred reality. While notorious and feared in their time, they have long since passed into colorful legend. Now, Rebecca Simon, a historian of piracy, colonial America, the Atlantic world, and maritime history, separates fact from fiction for us. Like so many, her own interest in pirates was sparked by Disneyland’s famous ride, but her journey would take her to earn a PhD from King’s College London and a career studying pirates:

My interest in pirates began on a superficial level. In 2003, Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl was released in theatres. I was 18 years old, and I saw it on a whim with some of my friends. Having grown up in Los Angeles, California, I had gone to Disneyland every year since I was a baby. Pirates of the Caribbean was always my favorite ride, although I don’t know why. Perhaps it’s because I have always been a beach girl, so naturally, I would like a water-based ride. Maybe it was the catchy song, “Yo-Ho and a Bottle of Rum.” Whatever it was, a visit to Disneyland was a bust if I could not get on that ride for some reason.

That said, I was very dubious about a film based on a ride. I only went to see that movie because I always enjoyed Johnny Depp films. To my surprise, I loved the film. The character Captain Jack Sparrow was intriguing and hilarious. The maritime mythology of cursed Aztec gold and a desire for treasure was fun but also fascinating to a budding history major like me. But that was it for my interest in piracy. To me, it was a fun subject about minor figures in history but all I really knew or cared about was swashbuckling hunts for buried treasure while Jack Sparrow asked, “Savvy?”

Things changed when I began my master’s degree in history in 2008. I was studying a new field, Atlantic history (now often referred to as transnational history) because it combined two of my favorite historical eras: Colonial America and early modern British history. I found the connections between the two regions and colonization to be both horrifying and captivating. My Atlantic history professor assigned a book called Villains of All Nations: Atlantic Pirates in the Golden Age by the historian Marcus Rediker. This surprised me because I never thought pirates were a subject to consider, but I was excited to read this book. Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl was still one of my favorite films. I looked forward to finding out how and why pirates buried treasure and how they developed such an adventurous culture.

An official trailer for Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl:

So, imagine my surprise when I read about how pirates were on the one hand much more complex, but also more straightforward than popular culture would have us believe. I quickly learned that everything we think we know about pirates is wrong.

The pirates we think about come from a period known as the Golden Age of Piracy, an era of three rounds of organized piracy from approximately 1670 to 1730.

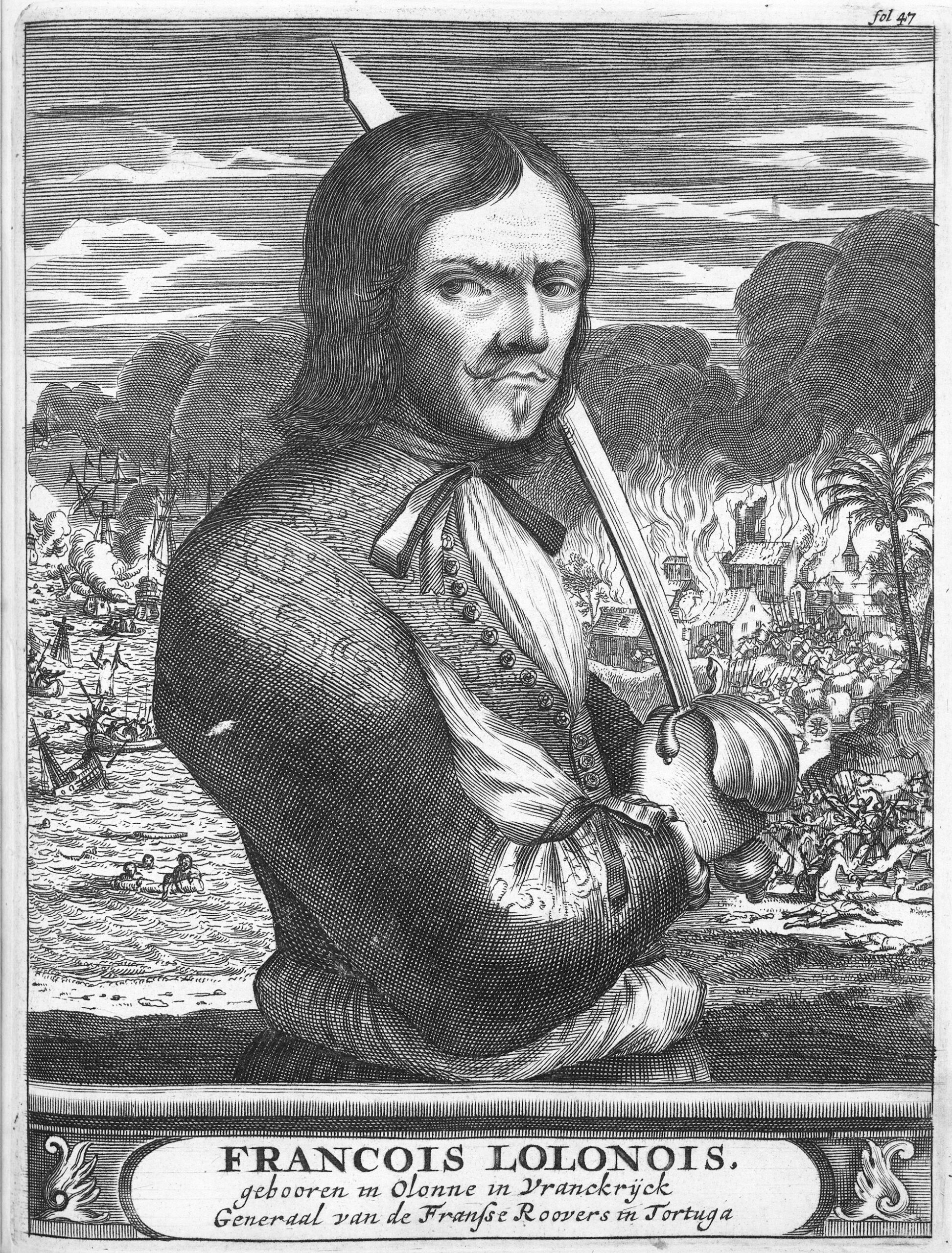

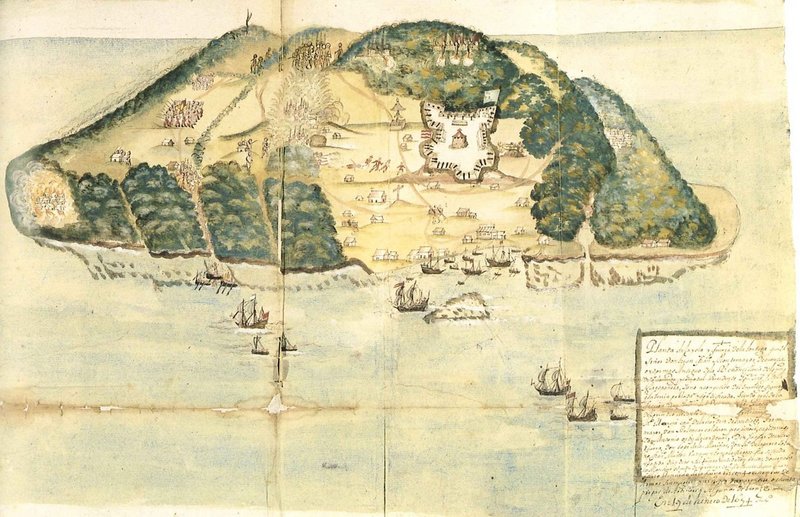

The first round (1670 to 1680s) was a period in which French buccaneers sailed around the Caribbean terrorizing Spanish ships. The buccaneers were known to hide out on and attack from land, and, interestingly, roast meat on their ships — a very risky endeavor at that time, due to the vessels’ wooden construction. British pirates also sailed, especially around Jamaica (an island so desirable that Britain went to war against Spain to control it), and set up a base in Port Royal in the southeast of the island. This round ended when the British negotiated peace with Spain by promising to protect their trade from pirates. Many of them scattered and quit piracy or turned to privateering, which meant that they were paid by the government to attack enemy ships.

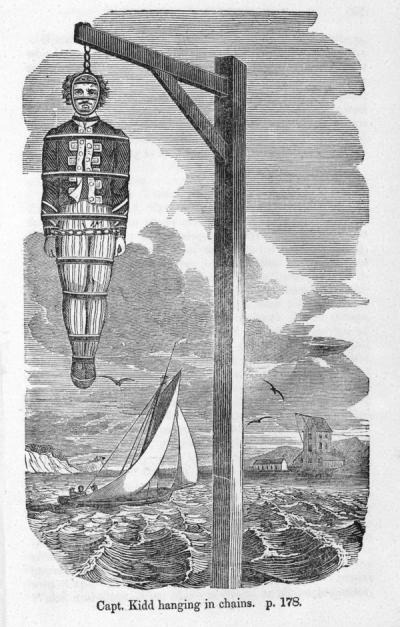

The second round refers to British pirates operating in the East Indies during the 1690s. These were pirates such as Henry Avery and William Kidd who attacked Mughal ships and nearly cost Britain their entire East India Company, which at that time dominated trade in the Indian Ocean region.

Then piracy goes on hiatus at the turn of the 18th century due to the outbreak of the War of Spanish Succession. The British government promised pardons to any pirate who agreed to fight for them as privateers. After the war ended in 1713, most of these privateers were out of work, and many banded together and terrorized merchant ships and trading lanes throughout the Caribbean and up and down the North American eastern seaboard.

This was the third round, the period that we are most familiar with today: it is the time of pirates such as Benjamin Hornigold, Blackbeard, Charles Vane, Anne Bonny, Mary Read, Samuel Bellamy, and Bartholomew Roberts along with thousands of others. Unlike the previous two rounds, none of these pirates were sailing under the guise of privateers. They were all in it for themselves.

One of the many myths I encountered, which is a disappointment to most, is that pirates never buried treasure. There has been a long-held belief that pirates collected gold, silver, and jewels and hid them in remote places that could only be uncovered through the possession of coded maps. However, pirates rarely came across these kinds of riches. Occasionally they were lucky enough to rob a ship that had some cash and valuables. Most of the time, however, about 50 percent of the goods they stole were intended to replenish their own ship, be it food, medicine, or supplies fit for repairing the vessel. The rest were items that could be sold at a decent price, such as alcohol, textiles, sugar, and occasionally enslaved people.

Capturing wealthy ships was the exception, not the rule. Two examples are Samuel Bellamy’s capture of the French ship, the Whydah, which was the wealthiest slave-trading ship in the world at the time. Unfortunately, just months later the Whydah would be wrecked in a storm off the coast of Massachusetts, killing all but two of the pirates including Bellamy. The other example is Blackbeard’s capture of the French slave ship, La Concorde, which he renamed Queen Anne’s Revenge. The ship contained several hundred enslaved people who Blackbeard initially freed but then later sold at slave markets.

There is one compelling case of a pirate having buried treasure: Captain William Kidd, a privateer-turned-pirate in the East Indies between 1696 and 1698. He captured an Armenian ship, the Quedah Merchant, which was said to be laden with gold and silver ingots and jewels. After Kidd’s arrest in 1699 in Boston, he wrote a letter to his former friend and financier, Lord Bellomont (governor of New York and Massachusetts) claiming he had stored all the riches on Gardner’s Island off the coast of New York. Bellomont initiated a search, which included arresting Kidd’s wife under suspicion of collusion, but nothing was found. Bellomont later wrote a letter stating that none of these items existed. But the rumors had already swept New England and London and searches commenced off and on for centuries. Even the writer, Robert Louis Stevenson, capitalized on this when he wrote his novel, Treasure Island, which was all about a treasure hunt.

But ‘treasure’ as we know it simply is not real. In fact, during the 17th and 18th centuries, the word ‘treasure’ simply meant ‘valuable’ or goods that could sell for a pretty penny.

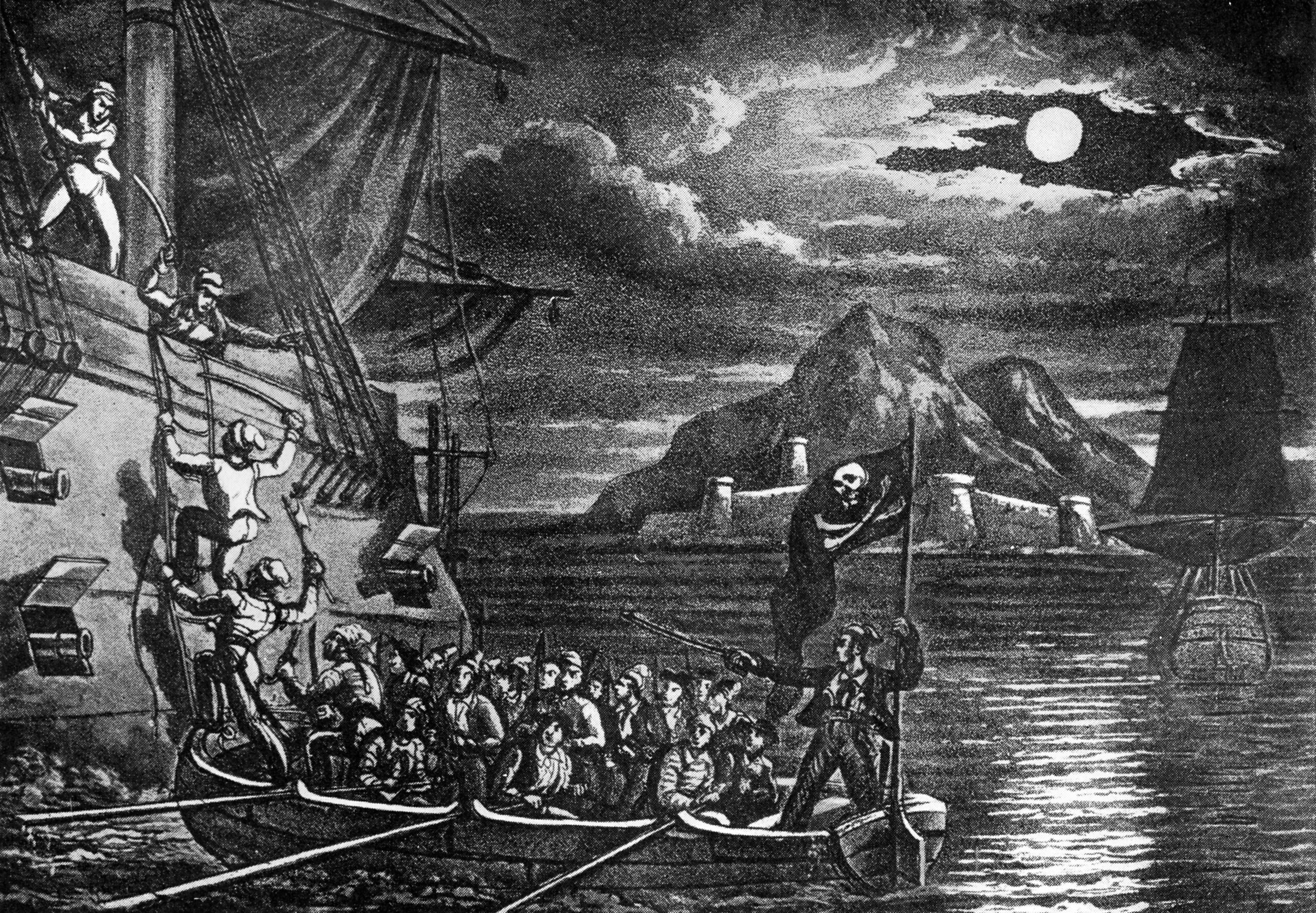

How did pirates go about procuring their profitable goods? Their most compelling weapon was their flag, commonly known as the Jolly Roger. The pirate flag as we know it has been around since the early 17th century, although its potent symbolism endures today. International maritime law required all ships to identify themselves by their flags, which made them a prime target for pirates. Pirates would hail their chosen victims and once that ship was too close to turn away, the pirates would switch out that flag for their own.

Initially, the pirate flags were plain red to be easily identifiable by their victims. Over time, pirates also adopted a black flag. These two colors indicated the pirates’ purpose. A red flag meant they would offer no quarter or mercy. A black flag stated they would give quarter provided their victims surrender quickly. Over time, the red flag faded in popularity and the black flag became synonymous with pirates. They became a great beacon, and many started to be adorned with designs unique to different ships. Bartholomew Roberts’s flag had his own self-portrait on it while Edward Teach, commonly known as Blackbeard, favored one with a devil and a bleeding heart.

Jack Rackham designed the skull and crossed cutlasses, which has become the iconic image attributed to pirates today. It seems counterintuitive that pirates would want to make themselves stand out so easily but announcing themselves often frightened their would-be victims into submission. Pirates and their victims were more likely to survive an attack if they cooperated.

Pirate attacks were violent and deadly, but not as much as one might think. The pirates’ goal was to get in and out as quickly as possible. The pirate quartermaster would often negotiate with the captain or carry out terrifying threats so they would comply easily.

Scare tactics were essential for pirates’ survival. The pirate Samuel Bellamy (active 1717-18) used theatrical attacks by having himself and his men charge onto ships completely naked, shocking their victims into submission. Blackbeard used his physical appearance by growing out his hair and sticking lit candles into his long beard, so the smoke made it look like he’d appeared out of hell. Methods like these worked well and their victims often surrendered quite quickly.

Blackbeard’s unique physical appearance was not the norm. Most pirates looked like any other common sailors of the time. Technically, that is exactly what they were. Captains dressed very well to show their status, but some might have been flashier than others thanks to their wealthy plunder. Jack Rackham became known as “Calico” Jack Rackham because he was known to favor very expensive clothing. Otherwise, pirates and sailors wore breathable clothing that was easy to move around in, such as baggy shirts and trousers with belts to hold tools and weapons.

Pirates wore shoes, although many went barefoot as it was easier to climb ropes that way. Some might wear handkerchiefs around their necks or hats for sun protection. Unless one sailed in the Royal Navy, practical clothes overruled strict uniforms. One item of clothing that people attribute solely to pirates, however, is the eyepatches they wore to help them see in the dark when going below ship. The idea is that they would have one eye adjusted to help them see better in low-light conditions. Whether or not this is true is inconclusive due to a lack of evidence outside of fiction.

Blackbeard’s flashy dress inspired centuries of infamous fictional pirates. Pirates in adventure stories and films have taken on identifiable features and/or clothing, beginning with the novel Treasure Island. The main antagonist, the pirate Long John Silver, was known for missing a leg and used a peg and a crutch to overcome his disability. This look would be immortalized by Robert Newton, the actor who played the character in the 1950 Disney adaptation of the novel. Not only that, but he is also the one who gave us the iconic pirate ‘accent’ with the “arr mateys,” which was simply an affectation of his native southwestern English accent.

Another famous fictional pirate is the Dread Pirate Roberts from the film The Princess Bride. He is interesting because the pirate is just a brand. Dread Pirate Roberts is a name bestowed over generations of pirates when various captains retire, but this is kept secret to keep up their fearful reputation. When we are introduced to this man, he is wearing all black. Many pirates did wear black, but the monochrome outfit sets Roberts apart from other fictional ones.

Finally, we have Captain Jack Sparrow from the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, who is the most decorated character. He has long hair in dreadlocks, beads in his beard, and wearing a flashy hat. Sparrow has no qualms about standing out and enjoys knowing people have heard of him. His actual outfit is fairly accurate, but he carries more material on him than the average pirate would.

A notable item that fictional pirates have are pets. Long John Silver famously has a parrot while Captain Barbossa has a monkey. There is an element of truth to this. Pirates, like many other people, loved pets and they sailed in tropical locales so many of them would bring tropical birds onto ships for entertainment and some companionship. Rats were a common reality on ships so many of them would have a resident cat or two.

Personal companionship is another complicated matter. There is a commonly held belief that pirates did not allow women on ships because they were bad luck. This was mentioned several times in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl and in the third season of the show Outlander. This idea likely comes from maritime mythology surrounding sirens and mermaids — mystical beings said to lure sailors to their deaths by seducing them with songs. It is true that many pirate captains did not allow women on board at all. Blackbeard banned them. Captain Bartholomew Roberts had a specific article in his pirate codes that stated, “No boy or woman to be allowed amongst them. If any man were to be found seducing any of the latter sex, and carried her to sea, was to suffer death…” It was less that women were unlucky and more that they were thought to cause distractions and discord amongst the men. They were also seen as unable to withstand the mental and physical rigors at sea.

But not all pirate captains were against women on board. Anne Bonny and Mary Read were two female pirates who sailed with Captain Jack Rackham in 1720 (the former of whom was married to Rackham). There have even been female pirate captains, such as Teuta of Illyria in Ancient Greece, Gráinne O’Malley in 16th-century Ireland, and Zheng Yi Sao in 18th-century China who was said to command a fleet of a thousand ships. But these were the exceptions in a violent, heavily male-dominated maritime world.

Companionship and release had to come from somewhere, leading us to a heavily debated topic: homosexual pirates. The opinions about this subject tend to be polarized with either a hard ‘no’ or ‘all pirates were gay.’ This is something almost impossible to quantify because there were no records of pirates’ sexual activity on ships. Homosexuality itself did not exist as a concept yet. Instead, it was merely terminology about specific sexual activities: ‘buggery’ and ‘sodomy,’ both of which were punishable by death via court-martial.

That does not mean same-sex relationships or sexual encounters did not occur. The British Royal Navy, for example, was rife with sexual abuse between officers and lower-ranked members. One captain named Samuel Norman ordered one of the younger men on the ship to “grab a pail of water … to wash his legs, thighs, and privy parts.” When the young man refused, Norman raped him, and this became an unfortunate reality throughout the journey.

In the above-mentioned pirate code from Bartholomew Roberts, ‘boys’ were banned alongside women. One could argue that he was trying to avoid children on ships, or he could have been banning all sexual partners. Statistically speaking, there were likely as many homosexual pirates on ships as there are in your current place of work. Pirates sometimes engaged in matelotage (from the French word for ‘sailor’), otherwise known as a same-sex union between two of them. Captains could facilitate weddings and these partnerships, so they were legal at sea. Matelotage linked two pirates together in a marriage-like fashion to indicate mutual respect and care for each other and to ensure that their prizes would go to a specific person should they die in battle. Matelotage was likely mostly used to ensure that a pirate’s family got his share of prizes in case he died but there is also the chance that some pirates got together out of love. An example of this is a matelotage agreement between pirates named Francis Reed and John Beavis in 1696, which stated: “Be it known to all men present that Francis Reed and John Beavis entered in censorship together. In case any sudden accident should happen to Francis Reed, that what gold, silver, or any other thing whatsoever shall lawfully become or fall to John Beavis [and vice versa].”

There is one known possible same-sex relationship between two pirates named John Swann and Robert Culliford. They met in the late 1690s in prison and became inseparable and both sailed with Captain William Kidd in the East Indies for a time. After Kidd landed in Madagascar, Swann and Culliford lived next door to each other. However, Swann decided not to continue with Kidd and Culliford and the latter would later hang with Kidd at Execution Dock.

Situational homosexuality is also common. In situations where men are confined together in small intimate spaces for long periods of time without much privacy for sexual release, they might turn to each other. In the 1650s, the French governor of the island of Tortuga, Le Vasseur, sent over approximately 1,500 female prostitutes because men were known to be having sex with each other. It is unknown whether this changed sexual activity on the island.

Whatever the truth is, the idea of same-sex relationships between pirates has become a trope in modern-day popular culture. The wildly-popular television shows Black Sails (Starz, 2014–2017) and Our Flag Means Death (HBO Max, 2022–present) both present touching relationships among pirates during a time in which this was forbidden and punishable by death. Pirates have come to be seen as transgressional figures against stifling political climates, so these portrayals have been welcomed and embraced.

Piracy has been a source of fascination for people for centuries. Pirates became popular literary figures starting with Captain Charles Johnson’s book, A General History of the Pyrates (1724) which later inspired Stevenson’s Treasure Island. From here is a domino effect of how pirates transitioned from historical figures to idealized antiheroes. Buried treasure, peg legs, eye patches, women as bad luck, and ideas of same-sex relationships all have their roots in history but changed into legend thanks to popular culture.

Rebecca Simon’s latest book, Pirate Queens: The Lives of Anne Bonny and Mary Read, is out now from Pen & Sword.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com