The governments of France, Germany, and Spain have awarded a contract to industry to develop flying demonstrators for a Future Combat Air System (FCAS), which will eventually include a manned New Generation Fighter (NGF) aircraft. The contract — worth 3.2 billion Euros, or around $3.4 billion at the current exchange rate — comes a week to the day after the United Kingdom, Japan, and Italy announced they would team up to jointly develop a new fighter jet, under the Global Combat Air Program (GCAP), which you can read more about here.

Significantly, the FCAS contract announcement says “in-flight demonstrations” are expected to be achieved by 2028 or 2029. However, the nature of the flying demonstrators that will be developed for FCAS remains unclear. While they may include some kind of manned fighter prototype, representative of the NGF, the multi-faceted nature of FCAS means they could also include drones, air-launched weapons, and potentially other aerial platforms.

In contrast, the GCAP project aims to have a fighter demonstrator in the air by 2027.

Today’s contract was awarded by the French General Directorate for Armament (DGA), the French government’s defense procurement and technology agency, on behalf of the governments of the three countries. Work will be carried out by France’s Dassault Aviation, the German division of Airbus, Spain’s Indra, plus their respective industrial partners. The other major industrial player is Eumet, the European Military Engine Team, which is headquartered in Germany and will be responsible for the powerplant for the NGF fighter jet.

“Dassault Aviation, Airbus, Indra, and Eumet welcome this major step forward that reflects the determination of France, Germany, and Spain to develop a powerful, innovative, and fully European weapon system to meet the operational needs of the countries’ armed forces,” a joint statement declared.

The contract covers what’s known as FCAS Phase 1B. Running for around three and a half years, this phase will include broader research and technology (R&T) elements, as well as the flying demonstrators themselves and related subsystems.

It’s worth noting, of course, that FCAS involves something of an alphabet soup of different interrelated acronyms, which can be confusing. It should also be pointed out that a separate FCAS exists in the United Kingdom, within which is the Tempest future fighter jet, which would appear now to have been rolled into the Global Combat Air Program (GCAP).

Airbus explained to The War Zone that the French, German, and Spanish FCAS refers to the ‘system of systems’ that will be introduced to service by those nations around 2040. This will include both newly developed technologies, as well as connecting these with existing equipment, like the Typhoon and Rafale fighter jets, plus the Airbus A330 MRTT refueling tanker. In French, FCAS is alternatively known as Système de Combat Aérien Futur (SCAF).

Work leading up to the definitive FCAS ambition is covered by the Next Generation Weapon System (NGWS) program, under which are all-new technologies, among them the New Generation Fighter (NGF). The aforementioned manned fighter will be capable of land-based and carrier-based operations.

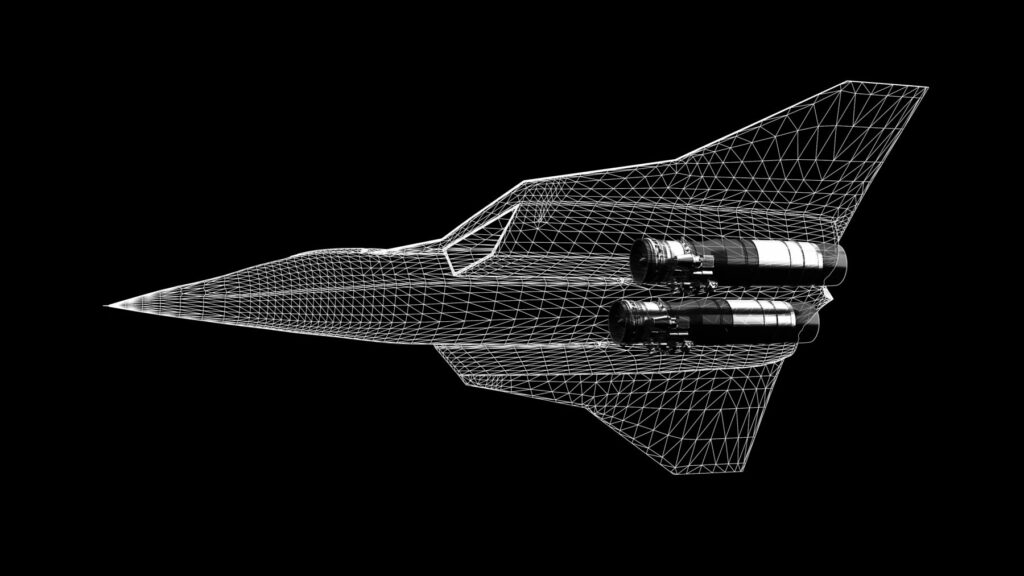

NGF is at the heart of FCAS, although it’s unknown exactly how this will take shape. A full-scale mock-up was unveiled at the Paris Air Show in 2019 but is likely only indicative of one of the possible concepts, several of which have now appeared, with differences also between Dassault and Airbus configurations.

We do know that the NGF is planned to incorporate stealth characteristics, especially to reduce the chance of detection by long-range enemy airspace surveillance, according to the German Ministry of Defense. In its description of NGWS, the same ministry also describes the “balancing act between high stealth capability and the best possible aerodynamics,” suggesting that there will be some kind of tradeoff between low observability as well as maneuverability and kinematic performance.

We also know that FCAS will benefit from low observable technologies that were tested under the Low Observable UAV Testbed (LOUT) program, a secretive effort that was first disclosed by Airbus in 2019. LOUT examined various different low-observable configurations and included a four-ton model used for aerodynamic and anechoic chamber testing. From what we know about the program at this point in time, no flying airframe was ever built or tested under LOUT. Of course, as well as NGF, there will be various unmanned systems in FCAS that are very likely to be even more stealthy and which may draw more heavily upon the LOUT experiments. You can read our complete analysis on LOUT here.

The requirement to have NGF — or a version of NGF — able to operate from French Navy aircraft carriers will bring additional challenges to the design, chiefly in the form of landing gear able to absorb deck landings, as well as catapult launch and arrester gear. The airframe would also have to be more robust for carrier operations, adding mass to the design, and that naval requirement would have to be accounted for in the wing and control surface design in order to allow for optimized carrier recovery. At the very least, this would necessitate a variant that is built for carrier operations, which would increase cost and timeline. The navalized NGF will eventually go to sea aboard France’s nuclear-powered New Generation Aircraft Carrier, scheduled to enter service in 2038, which you can read more about here.

Interestingly, it’s been reported that the NGF will be too large to be easily accommodated on the French Navy’s current aircraft carrier, the conventionally powered Charles de Gaulle. The new fighter is likely to weigh in the region of 33 tons, compared to around 27 tons for a fully loaded Rafale. A larger airframe could translate to considerable range, as well as the ability to carry a significant payload internally.

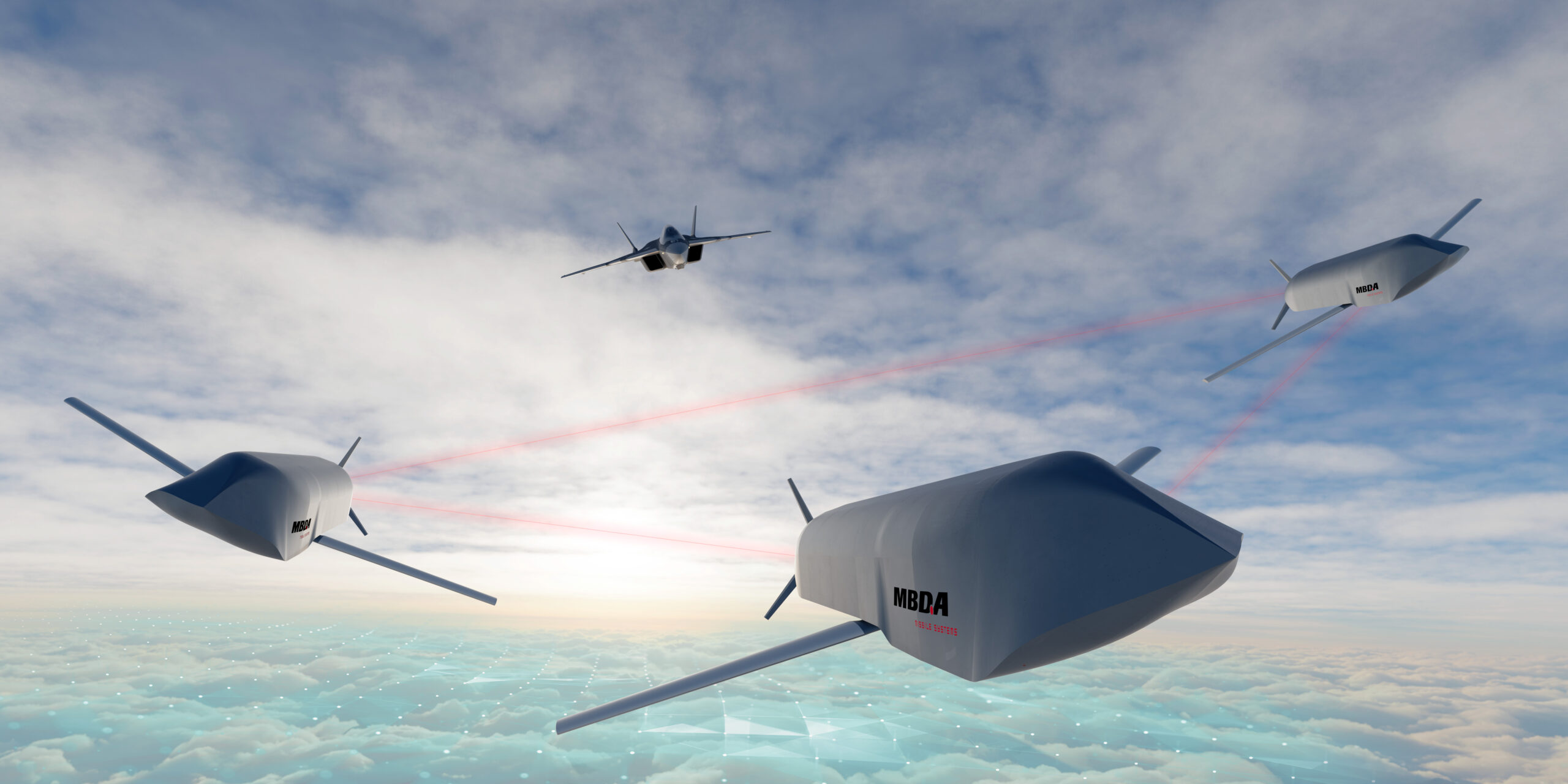

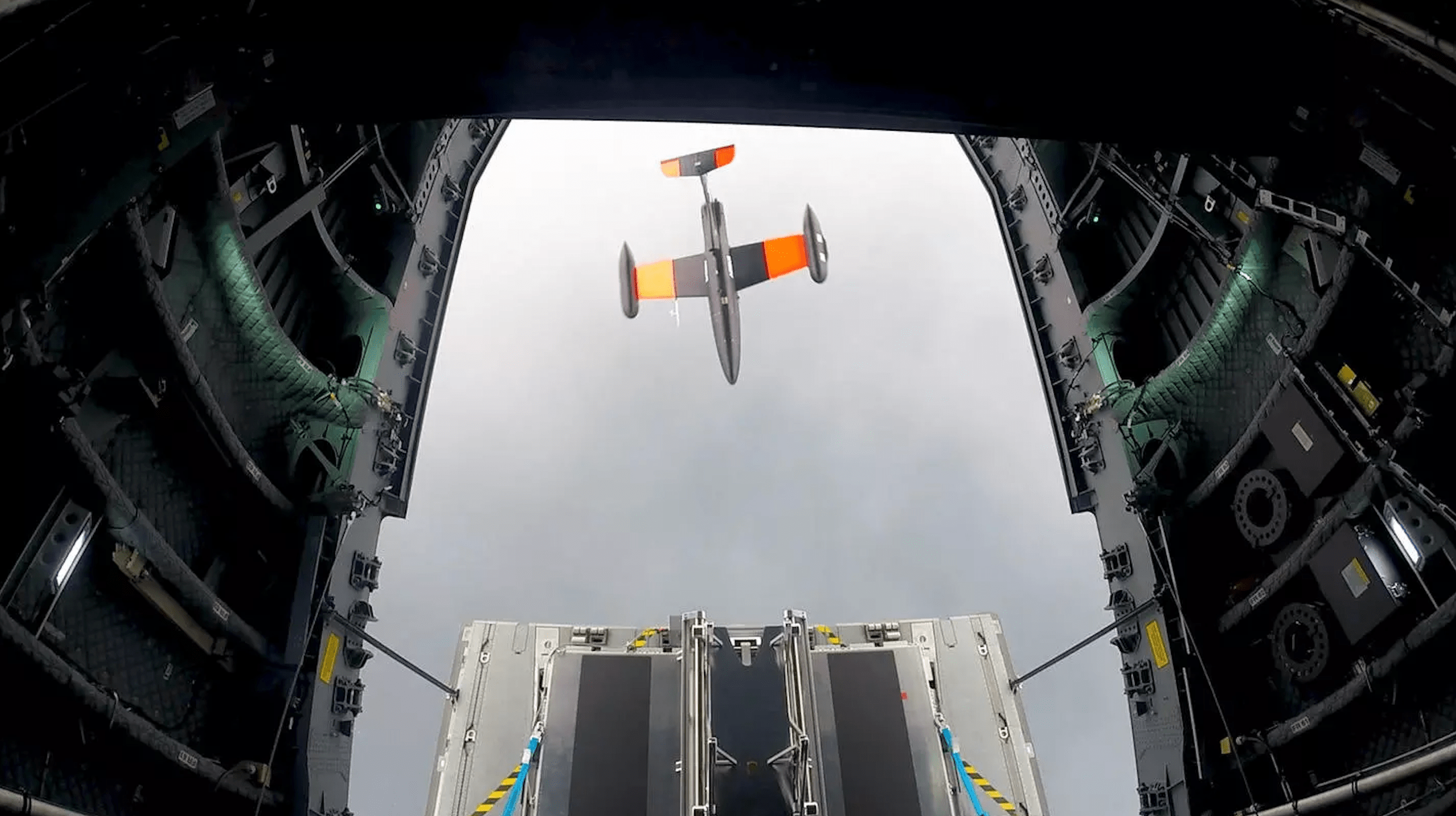

NGWS also includes other systems tailored to work alongside the NGF, including Remote Carriers (RC), which will fly in close cooperation with this and other manned aircraft, supporting various missions. At this stage, it’s envisaged that Remote Carriers will be launched by A400M transport aircraft motherships, each of which will carry up to 50 small or up to 12 heavy RCs. These will then join manned aircraft, operating, in the words of Airbus “with a high degree of automation although always under a pilot’s control.”

The NGF jets, the RCs operating with them as ‘loyal wingmen,’ and other assets will all be harnessed together via a Combat Cloud (CC) information network, also being developed under NGWS.

Earlier this month, Airbus demonstrated the first successful launch and operation of a Remote Carrier flight-test demonstrator — a surrogate Airbus Do-DT25 drone — from an A400M. In a separate test, conducted this summer, the company also ran a large-scale multi-domain flight demonstration, involving two fighter jets, a helicopter, and five Remote Carriers that teamed up to accomplish a mission. Both these experiments are highly significant within the scope of FCAS, which foresees seamless integration between manned aircraft, Remote Carriers, and other assets, via Combat Cloud.

We also now have a much better idea as to how the three main companies will act as “national coordinators,” dividing up the workshare between different companies and organizations in their respective companies. Within Phase 1B, areas will be allocated as follows:

Next Generation Weapon System (NGWS) consistency, demonstrations, and consolidation: Airbus, Dassault Aviation, and Indra will serve as co-contracting partners

New Generation Fighter (NGF): Dassault Aviation will be the prime contractor, with Airbus as the main partner for both Germany and Spain

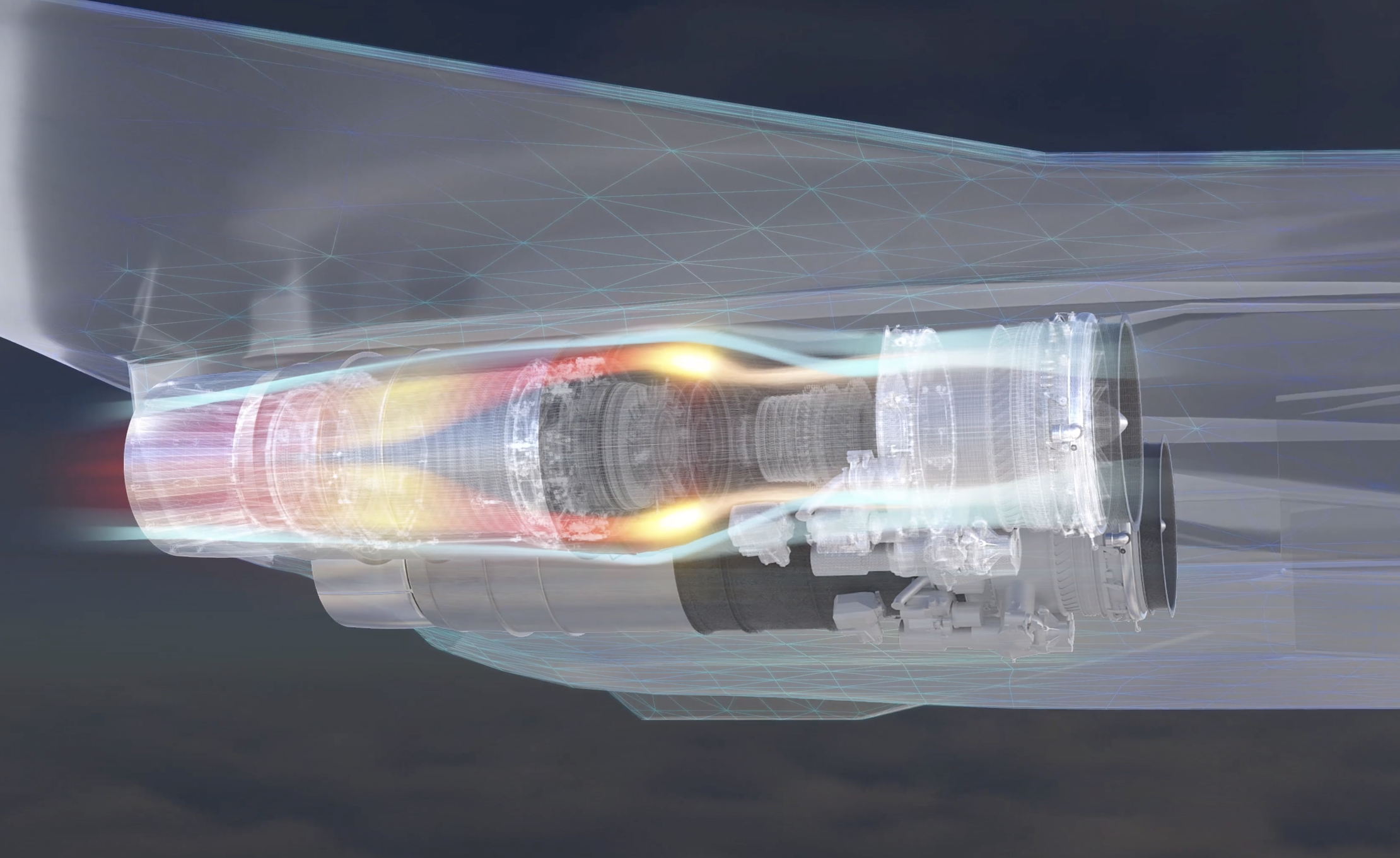

NGF engine: this will be handled by Eumet as the prime contractor. Eumet is a 50/50 joint venture between Safran Aircraft Engines for France and MTU Aero Engines for Germany. ITP Aero of Spain will be Eument’s main partner

Unmanned systems, Remote Carrier (RC): Airbus of Germany is the prime contractor, with MBDA of France and Satnus of Spain as main partners

Combat Cloud (CC): Airbus of Germany is the prime contractor, with Thales of France and Indra Sistemas of Spain as main partners

Simulation: to be handled by three co-contracting partners, comprising Airbus, Dassault Aviation, and Indra Sistemas

Sensors: Indra Sistemas of Spain is the prime contractor, with Thales of France and FCMS of Germany as main partners

Enhanced Low Observability (stealth): Airbus of Spain is the prime contractor, with Dassault Aviation of France and Airbus of Germany as main partners

Common Working Environment: to be handled by four co-contracting partners, comprising Airbus, Dassault Aviation, Indra Sistemas, and Eumet

Nailing down these industrial arrangements of the respective partners is a big deal in a program that has, in the past, been hampered by infighting based on intellectual property rights and workshare sizes.

These issues now seem to be resolved, Airbus stating that “Discussions held over the last months have enabled the creation of a solid basis for cooperation between industry and the three governments.”

Earlier this month, it was reported that the prime contractors — Airbus, Dassault Aviation, Indra, and Eumet — had finally reached an overall industrial agreement, paving the way for the award of the Phase 1B contracts.

Previously, FCAS work had been carried out under Phase 1A, launched in early 2020, which was primarily an R&T and development effort. This aimed to identify the key technologies required to achieve the FCAS goals, which will now be fully realized as flying demonstrators and related technologies under Phase 1B.

Clearly, there is much development work still ahead under Phase 1B before we start to see flying demonstrators. Although it would seem logical for at least one of these demonstrators to be some kind of flying prototype for the NGF, we don’t even know that for certain. As well as the demonstrator for the GCAP program, the U.S. Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program also has had some kind of demonstrator flying since at least September 2020.

While the contract for Phase 1B is a major step in the right direction for FCAS, there will be plenty of serious challenges ahead, too.

By their nature, stealth combat aircraft programs tend to involve very long development times as well as very high costs. As with GCAP, having three nations contributing to costs and industrial capacity should help keep timelines and costs manageable. At the same time, however, the program also needs to ensure that the different — potentially conflicting — national requirements are met and that industrial partners remain happy with workshare and access to technologies. In the past, these have been stumbling blocks for FCAS. It would appear, too, that GCAP’s inclusion of Japan could be a very smart move, leveraging the considerable financial clout that Tokyo brings, especially as its defense budgets steadily rise. Before joining GCAP, Japan was already expecting to spend around $40 billion developing its new fighter jet.

Meanwhile, some air force leaders in Europe have called for the two rival FCAS efforts (British-led, and Franco-German-Spanish) to be fused together to ensure that financial resources are better invested across the continent.

Although Dirk Hoke, the former CEO of Airbus Defence and Space, previously argued that Europe “can’t afford two new [FCAS] systems,” the United Kingdom has been more resistant to a possible merger.

Last year, Air Cdre Jonny Moreton, the U.K. Program Director Future Combat Air Program at the British Ministry of Defense, told Tim Martin of Shephard News: “We have absolutely no intention of joining a French-German-Spanish Future Combat Air System program.”

Overall, Hoke’s statement may well prove to be true, with genuine concerns persisting over whether European powers will actually be able to pay for two competing stealth jet programs.

Perhaps, with so many shared ambitions and technological crossover, at least some elements of the two programs — for example, weapons and sensors — might eventually fuse in some way.

For the time being, at least, there are two equally ambitious next-generation combat aircraft programs underway in Europe. For both, the countdown is now on to have flying demonstrators of some kind in the air before the end of the decade.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com