The U.S. Army plans to substantially increase its arsenal of Coyote counter-drone interceptors, as well as associated launchers and radars, in the next five years or so. The service says it wants to buy 6,000 jet-powered Block 2 variants, which carry an explosive warhead to destroy their target, and 700 more Block 3 versions that utilize an unspecified “non-kinetic” payload.

The Army disclosed the details about its Coyote-related purchase plans for Fiscal Years 2025 through 2029 in a contracting notice about an expected sole-source contract to manufacturer Raytheon released earlier this week. In addition to the Block 2 and Block 3 interceptors, the service is looking to acquire 252 fixed launchers, 52 mobile launchers, 118 fixed Ku-band radars, and 33 mobile radars. Under the deal, Raytheon would also provide support for the maintenance and repair of at least 15 Coyote systems both in the United States and unspecified forward-deployed locations around the world.

The announcement does not include any projected costs, but the unit price of a Block 2 Coyote is reportedly around $100,000 – a relatively low cost compared to traditional surface-to-air missiles. As such, the cost to purchase the 6,700 interceptors could be up to $670 million.

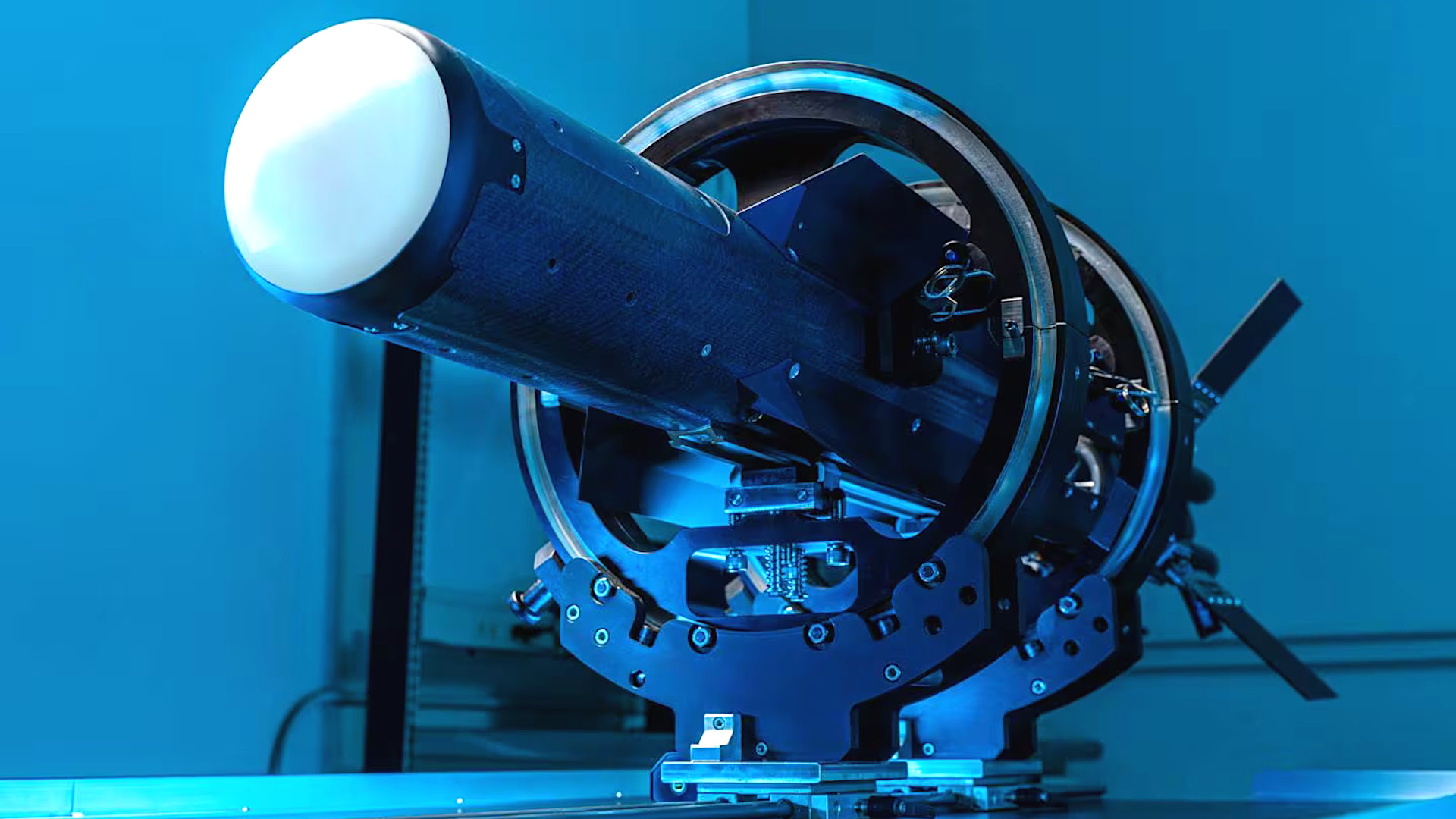

The Block 2 Coyote, which first emerged publicly in 2018, is derived from Raytheon’s original Block 1 Coyote drone, which is a multi-purpose canister-launched design that you can read more about here. However, the Block 2 differs substantially from its predecessor, having a completely different missile-like configuration and a jet propulsion system. This version of Coyote uses a small radar seeker to zero in on its target. A Block 2+ subvariant with an improved seeker has since been developed.

The Block 3, which has been in testing since at least 2020, is based on the original Coyote design with its electric motor-driven pusher propeller. Raytheon has not disclosed specifics about its “non-kinetic” payload, but says it has demonstrated the ability to engage multiple different types of drones at once. This would seem to point to some kind of electronic warfare system or high-power directed-energy weapon.

Raytheon has also said that Coyote Block 3s can be recovered and refurbished for reuse, whereas Block 2 types are designed to be single-use interceptors. The Army has Coyote Block 2s in active service now, including at forward locations in the Middle East. Block 2s were reportedly used to down drones attacking a U.S. outpost in Syria in January. It is unclear if the service has fielded Block 3 versions.

The Army currently fields mobile and fixed position Coyote counter-drone systems, also known as the Mobile, Low, Slow, Unmanned Aircraft Integrated Defeat System (M-LIDS) and Fixed Site LIDS (FS-LIDS).

The current M-LIDS configuration consists of a 4×4 M-ATV mine-resistant vehicle with a turret that is armed with a two-round Coyote launcher, as well as a 30mm XM914 automatic cannon. The turret has electro-optical sensors to help spot and track incoming drones and the vehicle also has a mast-mounted Ku-band radar to cue the Coyotes. The complete M-LIDS system also includes a second M-ATV vehicle equipped with additional sensors and electronic warfare capabilities. There has been talk in recent years about combining these capabilities onto a single platform, possibly one utilizing the 8×8 Stryker armored vehicle.

FS-LID is a two-part palletized system. One pallet has a four-round Coyote launcher and a sensor array, while the other has a Ku-band radar. The radars used on M-LIDS and FS-LIDS are related in design, but are not the same. The palletized type is larger and more capable.

Whether or not the Army’s new purchase plans could include new or improved M-LIDS or FS-LIDS configurations, such as a Stryker-based M-LIDS variant, is unclear. It is also unknown why the number of mobile radars the service plans to acquire is less than the number of mobile launchers given the current M-LIDS configuration. Fixed site launchers could be tied to a single radar. M-LIDS and FS-LIDS can also be networked together with other offboard sensors and layered in with other types of effectors.

What is clear is that the Army plans to significantly expand the size of its Coyote-based counter-drone system arsenal by the end of the decade. This, in turn, speaks to the very real threat that drones, including lower-end designs and weaponized commercial types, pose on and off traditional battlefields. These threats are only expected to grow in the coming years.

In the past few months, U.S. forces in Iraq and Syria have been subjected to a wave of drone and other indirect fire attacks from Iranian-backed groups. These incidents, which are ostensibly in retaliation for U.S. support for Israel’s ongoing operations targeting Palestinian militants, have caused dozens of injuries. Hamas militants also used weaponized drones in their brazen terrorist attacks on southern Israel on October 7, which precipitated the current crisis in the region.

The war in Ukraine, where the use of loitering munitions, kamikaze drones, and other types of weaponized uncrewed aerial systems has become ubiquitous on both sides, has also underscored the need for the U.S. military to expand its ability to defend against uncrewed aerial systems.

“The Army is very much watching the kinds of drone/counter-drone war in Ukraine and doing the best we can to incorporate those lessons into our future plans,” Doug Bush, Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology, said at a press briefing in September.

At the same time, the Army and the rest of the U.S. military continue to play catch-up in responding to these threats, which are not new at this point. Since 2020, the service has been in charge of a Department of Defense-wide Joint Counter-small Unmanned Aircraft Systems Office, or JCO, to try to better coordinate and advance efforts to acquire multiple types of country-drone capabilities.

“No one system is going to be able to defeat all these threats,” Army Maj. Gen. Sean Gainey, Director of the JCO, said at the Association of the U.S. Army’s main annual conference in October. “If somebody has that system, come see me. I’m looking to talk to you, and we have some money that we’ll be ready to invest in.”

M-LIDS and FS-LIDS already represent just some of the counter-drone capabilities branches of the U.S. military have been working to develop and field in recent years. The U.S. Marine Corps notably has a similar system to M-LIDS, called the Marine Air Defense Integrated System (MADIS). The current version of MADIS features a similar turret with a 30mm cannon, but with a two-round launcher for Stinger heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles instead of Coyotes, all mounted on a 4×4 Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV).

Like M-LIDS, the complete MADIS system includes a second JLTV-based configuration without Stingers, but with an active electronically-scanned radar array and other additional sensors. Small active electronically scanned array (AESA) radars are becoming increasingly common components of counter-drone systems.

The Army and other services have been pushing to deploy counter-drone electronic warfare systems, including vehicle-mounted and man-portable types, and directed energy weapons (including lasers and high-power microwaves), as well.

A key issue in all of this remains the cost ratio to shoot incoming drones, especially swarms of lower-tier types that cost just a fraction of interceptors, even lower-cost ones like Coyote. Defense contractor Anduril recently publicly unveiled a new jet-powered counter-drone interceptor called Roadrunner-M that is looking to get after these challenges in new ways, including by being readily reusable if it does not prosecute a target in the course of a single sortie. You can learn more about Roadrunner, which has been under development for U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM), here.

Whatever other counter-drone capabilities come into service across the U.S. military, the Army has now made clear that it sees Coyote-based systems as central to protecting its forces from uncrewed aerial threats in the coming years.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com