General Atomics has unveiled a new concept for how its MQ-9B SkyGuardian drone might be employed in the future, as a launch platform for U.S.-Norwegian Joint Strike Missile cruise missiles. Utilizing MQ-9-series uncrewed aircraft as weapon trucks loaded with stand-off munitions could be one way to help ensure their relevance in future high-end conflicts.

An artist’s conception of an MQ-9B in Royal Australian Air Force markings and armed with a pair of Joint Strike Missiles (JSM) under each wing is currently on display at the Avalon airshow in Australia, which wraps up this week. The MQ-9B is an evolution of the MQ-9 Reaper that has greater range, endurance, and maximum payload capacity over its predecessor, among other improvements.

“That configuration is somewhat notional and meant to inspire a conversation about the possibilities for future use of the aircraft,” C. Mark Brinkley, a spokesman for General Atomics, told The War Zone. The MQ-9B in the company artwork also shows maritime search radar installed under the drone’s rare fuselage and two Sledgehammer electronic warfare pods under its wings. The pods could be used to launch electronic attacks on enemy forces or for self-protection, as well as for gathering electronic intelligence.

Though the configuration and stores loadout is notional, “GA-ASI has conducted an internal feasibility study regarding integration of the JSM onto our MQ-9B platform, and found the weapon meets those requirements,” he added. “Integrating weapons and other payloads onto our platforms is something we take pride in and we have a great track record in that regard, from Hellfire missiles to JDAMs and more.”

U.S. defense contractor Raytheon and Norwegian firm Kongsberg jointly developed the JSM. The stealthy cruise missile, which is designed to be air-launched, is derived from the primarily surface-launched Naval Strike Missile (NSM) that the two companies also previously collaborated on.

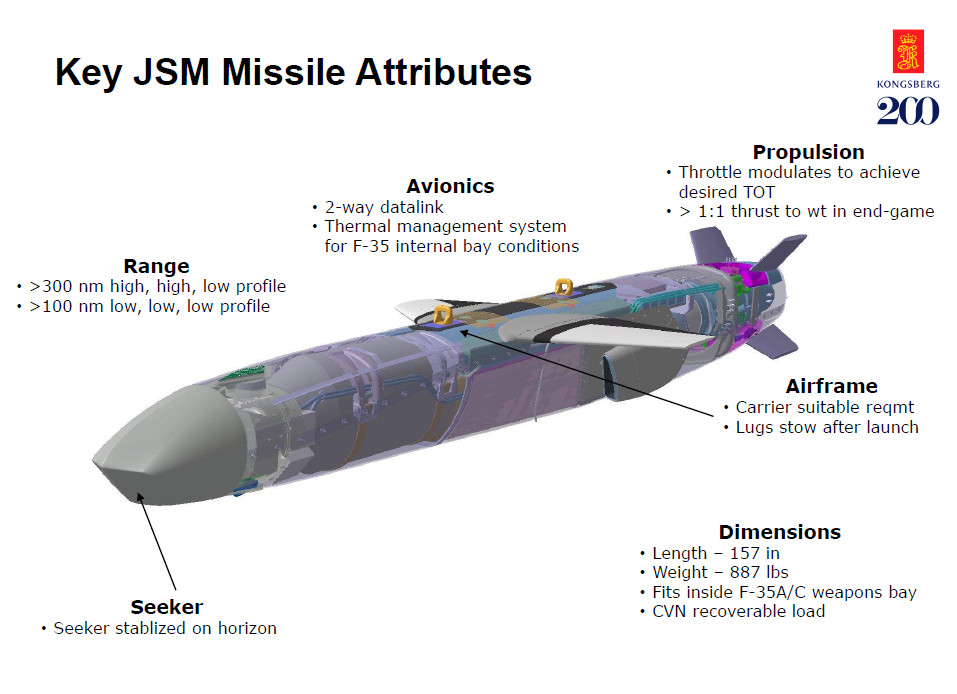

Kongsberg has said in the past that the JSM has a range of at least 300 nautical miles when set to fly to its target in a high-low profile. This involves the missile cruising at higher altitudes to the target area before diving down for its run-in to the target area ahead of the terminal phase of its flight. The JSM missile has a range of around 100 nautical miles, roughly equivalent to that of the NSM, when employed in its low-low mode, where it flies at low altitude throughout its entire flight, according to the Norwegian company.

JSM and NSM both feature a multi-mode guidance package to includes a GPS-assisted inertial navigation system (INS) system coupled with a terrain recognition capability, as well as an imaging infrared seeker. The seeker is a passive sensor making it immune to radiofrequency jamming.

There has been talk about integrating an additional seeker designed to home in passively on a target’s radiofrequency emissions onto JSM in the past, as well.

In their current form, JSM and NSM can be employed against ships and targets on land. They also have a two-way datalink allowing for updated targeting information to be sent in flight, improving accuracy, or for complete retasking from one target to another.

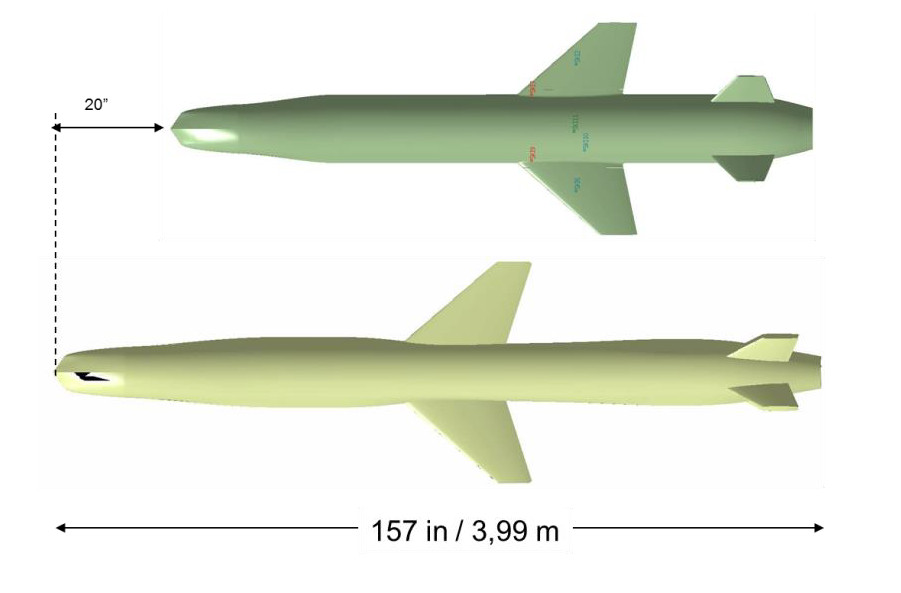

The JSM is larger than the NSM, but is still relatively compact. The JSM is 157 inches, or over 13 feet long, and around 917 pounds (416 kilograms). Its form factor was crafted around a Norwegian Air Force requirement that it fit inside the internal weapons bay on an F-35A Joint Strike Fighter. As a result, JSM will also fit internally on the F-35C variant.

The F-35B, which has smaller internal weapons bays than the F-35A and C, could carry the JSM, too, but would have to do so externally. This would be an option for the F-35A and C, as well. Kongsberg has also conducted JSM fit checks to demonstrate the basic ability of the F-16 Viper, F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, and F-15E Strike Eagle to carry the missile externally.

GA-ASI’s exploration of the feasibility of integrating JSM onto the MQ-9B would appear to be the first instance of talk about adding this weapon to an uncrewed platform. This could present an attractive combination that could provide a lower-cost way to increase the total volume of stand-off strikes.

The U.S. Air Force, among others, has been very actively exploring various ways to do just this. This is being driven in large part by the very real likelihood that any future major conflict, such as one in the Pacific region against China, would present a need to rapidly prosecute thousands of individual targets across a broad area.

On top of this, non-stealthy drones like the MQ-9 series have been shown in recent years to be vulnerable even to opponents with relatively limited air defense capabilities. The U.S. Air Force, the current largest operator of MQ-9s worldwide, has notably been pushing to stop purchasing any more of these drones and to start divesting significant portions of its fleet in favor of new, more survivable designs.

So, acting as weapon trucks for stand-off munitions like the JSM could offer one of a number of ways for them to still provide meaningful support, even in medium-to-high-threat environments. With the JSM’s networked nature, an MQ-9 could potentially launch these particular missiles using off-board targeting information. This, in turn, would allow the drones to fly along routes that are even more geared to keeping them as far away, or otherwise concealed, from threats as possible.

All this being said, GA-ASI has acknowledged that this concept has potential limitations.

“Taken literally, in terms of what can happen today, an MQ-9B equipped in this fashion would be trading significant endurance for significant offense, both electronic and kinetic,” General Atomics spokesperson C. Mark Brinkley explained to The War Zone. “One must imagine this aircraft has been carefully outfitted with a very specific mission in mind, and is not simply patrolling the area.”

Reducing the total payload weight, such as by carrying only two JSMs instead of four or eliminating one of the Sledgehammer pods, could give back some of that lost range and endurance, he noted.

The addition of JSMs to the MQ-9B’s arsenal could be combined with other future capabilities to further expand the options for employing these drones. For instance, GA-ASI separately announced last year that it was developing a conversion kit for MQ-9-series drones to allow them to operate from big deck amphibious assault ships and aircraft carriers.

It’s also worth noting that GA-ASI has “not engaged in any physical integration work [relating to JSM] to date,” but envisions “it as a future option for MQ-9B customers around the world as the payload develops further,” according to C. Mark Brinkley.

It’s not clear which existing MQ-9 customers, or future ones, might be interested in this pairing now. The display at Avalon makes sense in the context of Australia’s past interest in both JSM, albeit as a weapon for its F-35As, and in the MQ-9B. However, the Australian authorities announced their intention to halt a planned purchase of MQ-9Bs last year for unclear reasons.

The Japan Self-Defense Forces, which are buying JSMs for its F-35As, is now set to trial the maritime-focused SeaGuardian variant of the MQ-9B. Japan’s Coast Guard is already flying the SeaGuardian in a non-combat configuration. The U.S. Air Force has itself recently begun operating MQ-9s from Kanoya Air Base in Japan.

The only other two known JSM customers to date are Norway and Finland, the latter of which has also evaluated the MQ-9 in recent years.

The U.S. Air Force has been involved in the work to integrate JSM on various aircraft, including the F-16, and could have an interest in this concept. In addition, in December 2022, Air Force teamed up with the U.S. Navy for an exercise in the Mediterranean Sea nicknamed Jackpot Hooligan II that, in part, explored how MQ-9s might be able to support maritime strike operations in the future.

The U.S. Marine Corps, which is already working to field NSM in a ground-launched configuration, is also now flying MQ-9s. The Navy has also been integrating NSM onto its Independence class Littoral Combat Ships (LCS) and could deploy that missile on other vessels in the future too.

A number of other countries are also in the process of acquiring MQ-9Bs, or are set to in the coming years, too. This includes Taiwan, where the potential to equip the drones with stand-off cruise missiles might be very appealing as part of the island’s efforts to bolster its capabilities to counter a potential future intervention by Chinese forces from the mainland. Various types of Air and surface-launched anti-ship and land-attack cruise missiles are already important components of Taiwan’s defense plans.

The combination of the JSM and the MQ-9B could be appealing to entirely new customers, as well. The pairing could offer a pathway with a lower barrier of entry to acquiring a more robust standoff aerial strike capability, especially for smaller military forces. This is notably part of the arguments in favor of supplying MQ-9 variants to the Ukrainian armed forces, as you can read more about here.

Regardless, it will certainly be interesting to see how the idea of arming MQ-9s with JSMs, which could help breathe new life into this family of drones, continues to evolve.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com