The U.S. military has begun a new formal effort to explore options for how to better defend the homeland against the threat posed by ever-more advanced Russian and Chinese cruise missiles. This might include the return of domestic surface-to-air missile sites at critical locations across the country, though not on a scale that was seen during the Cold War. Directed energy weapons, as well as an expanded sensor and command and control infrastructure, bolstered by artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies, have also been discussed in the past as part of an improved cruise missile defense ecosystem.

Inside Defense first reported earlier today that the Air Force had kicked off the “air and cruise missile defense of the homeland analysis of alternatives” back in July. A year before that, the Pentagon had selected the service to lead this effort, which is expected to eventually involve contributions from all of the branches of the U.S. military and the Missile Defense Agency (MDA). This new effort will leverage work done in the course of a number of other U.S. military domestic air defense planning studies over the better part of the past decade.

“The AOA [analysis of alternatives] is starting in earnest and [is] going to churn out some program and investment analyses that will then lead into the budgets over the next couple of years,” one of two unnamed senior defense officials said, according to Inside Defense.

“Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks has directed the Air Force, which is spearheading the project, to think about one batch of initial investments that can be achieved in the 2026 five-year spending plan… And then identify a second basket of more advanced capabilities to reach for in the 2030 five-year spending plan,” Inside Defense further reported. “The expectation is that the AOA will recommend an amalgamation of existing systems and new capabilities.”

Beyond this, specific details about exactly what the Air Force may already be exploring with regard to improving homeland defense capabilities against incoming cruise missiles remain limited.

The War Zone has reached out to the Air Force for further information about the AOA, including whether or not it is completely limited to cruise missile defense. Relevant capabilities to protect against cruise missiles could easily be applicable to other threats, including the increasing dangers posed to domestic critical infrastructure by various tiers of armed or weaponized uncrewed aerial systems. As underscored by the current conflict in Ukraine, the line between traditional cruise missiles and kamikaze drones is already very blurry.

It is no secret that the U.S. military has a long-standing concern about the threats posed by cruise missiles, which are increasingly proliferating, even to non-state groups, to its forces and facilities abroad and at home. Over the past few decades, U.S. government fears have steadily grown about the danger these weapons pose to the homeland more broadly. In addition to the Russian and Chinese armed forces developing and fielding ever more capable designs, including hypersonic types, both of those countries have been expanding their launch platform options, especially newer, more capable missile submarines.

“The thing that I really want to emphasize here is that the homeland is not a sanctuary any longer,” U.S. Air Force Col. Kristopher Struve, the vice director of operations for the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), said during a virtual roundtable hosted by the Missile Defense Advocacy Association (MDAA) in 2021. “There are opportunities for our adversaries to employ weapons from distances that they could strike critical infrastructure in the United States early in a conflict and create some challenges for us to produce our military power.”

These are the realities that have prompted the Pentagon to task the Air Force with exploring a holistic, multi-faceted approach to improving the nation’s defenses against cruise missiles. Currently, the vast majority of standing domestic air defense capacity in the United States is provided by a relative handful of fighters sitting on alert at bases near key locales.

The only real permanently deployed ground-based capability within the continental United States are the National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (NASAMS) and AN/TWQ-1 Avengers positioned in and around the greater Washington, D.C. area, also known as the National Capital Region (NCR). There are additional surface-to-air missile units based in the United States that could be deployed in the event of a war or other major crisis, but they are limited in number.

So, an expanded and improved network of surface-to-air missile sites within the borders of the United States is known to be one part of these discussions.

In recent years, the Air Force, in cooperation with the U.S. Army, has publicly been working to expand NASAMS counter-cruise missile capabilities with a particular focus on homeland defense. The Air Force has also been testing more novel ground-based means of kinetically destroying incoming cruise missiles, including a large-caliber gun firing extremely fast-flying projectiles called the Hypervelocity Ground Weapon System (HGWS).

Documents released along with the Pentagon’s 2023 Fiscal Year budget proposal showed plans to conduct a test of a prototype HGWS together with NASAMS sometime between the beginning of July and the end of September of this year. However, it is unclear if this has occurred or is still scheduled to take place.

The Army, as well as the U.S. Marine Corps, are both in the process of acquiring new surface-to-air missile systems – Enduring Shield and Iron Dome, respectively – driven in large part by a desire for new counter-cruise missile defenses for forces deployed abroad. These systems could potentially be used to provide additional, if highly localized air defense capacity within the United States.

Beyond ground-based kinetic defense options, the Air Force has demonstrated a capability to shoot down enemy cruise missiles using aircraft armed with laser-guided 70mm Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System II (APKWS II) rockets, as well. Other kinetic and non-kinetic capabilities, including directed energy weapons and electronic warfare systems mounted on various platforms, could be part of the final domestic cruise missile defense equation.

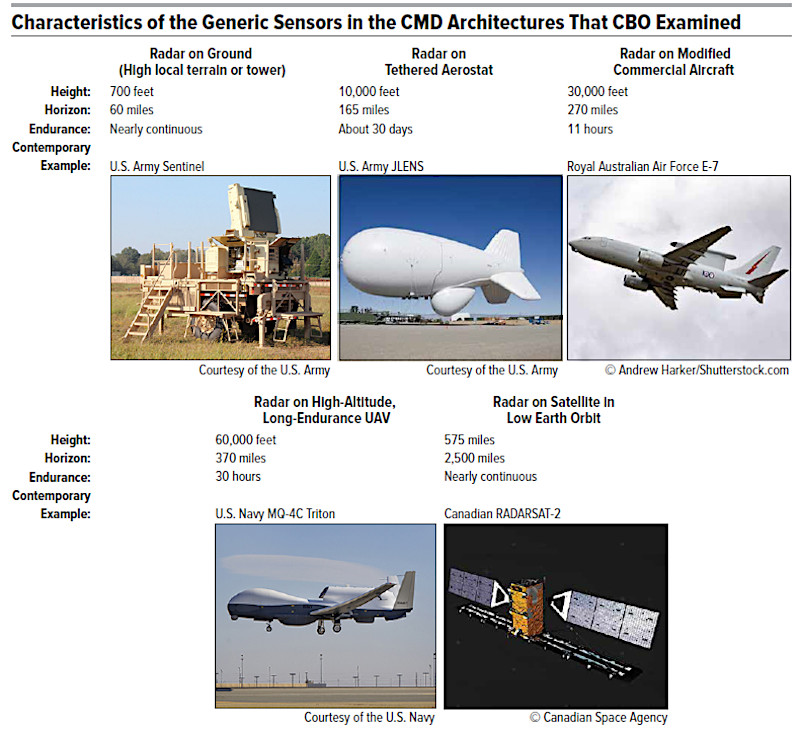

A robust targeting infrastructure, consisting of radars and other sensors, will also be necessary. Detecting and tracking cruise missiles, which generally fly at very low altitudes, and that might be flying at supersonic, supersonic, and now hypersonic speeds, is notoriously difficult.

A key reason beyond the Air Force’s refitting of F-15C/D Eagles with AN/APG-63(V)3 active electronically scanned array (AESA) radars in the past was to provide them any improved ability to spot and track cruise missiles. With the F-15C/Ds now in the process of being retired, many of the service’s F-16C/D Viper fighters are getting new AESA radars in large part for the same reason. The Air Force’s future F-15EXs, an acquisition program that is very much in flux currently, will also have AESA radars.

Creating an elevated sensor platform with good look-down visibility was the key driver behind the Army’s abortive Joint Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense Elevated Netted Sensor System (JLENS) radar blimp program. That effort began in 1996 and was canceled some two decades later after numerous cost overruns, delays, and other issues. In a particularly infamous incident in 2015, a prototype JLENS aerostat deployed at the Army’s Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland became untethered and drifted into neighboring Pennsylvania, with its snapped mooring line knocking down power lines along the way. It finally lost sufficient altitude to end up tangled up in a tree.

Furthermore, command and control networks will be required to link everything together. The Army is already in the process of fielding a new centralized air and missile defense networking capability, called the Integrated Battle Command System (IBCS), which you can read more about here. Advanced networks are a key part of the Air Force’s larger Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) initiative, as well.

The U.S. government also has a long-standing air defense partnership with Canada through NORAD, which would also be another factor in this future planning.

Overall, “Air and Cruise Missile Defense of the Homeland is very clearly not just a few things – it is a lot of things across a lot of different domains,” the first senior defense official told Inside Defense, according to its report today. “One thing we found [already]… is that there are a lot of capabilities that could be applied to this problem set, they’re just not aligned to [the cruise missile defense mission set.]”

“When we determined who needed to be the lead, we had to take into account the whole of the kill chain – not just the defensive part,” a second senior defense official also told that outlet. “That’s what really led us to the Air Force as the lead because they do a lot of work and those other domains, which include that early warning and that long-range surveillance, which is critical to the problem.”

Last year, the Defense Science Board notably published an unclassified summary of a future U.S. domestic air defense study it had conducted that called for “an adaptable, scalable, and affordable framework… that incorporates emerging technological innovations to ensure all-domain awareness, assured tracking, secure command and control, and affordable engagements.” It recommended leveraging of technologies including “artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML), multi-statics, directed energy, proliferated LEO [low Earth orbit satellite] constellations, and multimodal seekers, as supported by advances in big data analytics and digital engineering.”

Artificial intelligence and machine learning could be very valuable for helping air defenders rapidly prioritize which incoming threats to respond to and do so in the most efficient manner possible, as well as simply aiding them in the initial detection of those targets. It might even alert U.S. forces to the potential for strikes before they are even launched.

“The machine learning and the artificial intelligence can detect changes [and] we can set parameters where it will trip an alert to give you the awareness to go take another sensor such as GEOINT [geospatial intelligence] on-satellite capability to take a closer look at what might be ongoing in a specific location,” U.S. Air Force General Glen VanHerck, head of NORAD and U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM), explained to reporters in 2021 following a series of tests called the Global Information Dominance Experiments (GIDE). “What we’ve seen is the ability to get way further what I call left, left of being reactive to actually being proactive. And I’m talking not minutes and hours, I’m talking days.”

The Defense Science Board, a U.S. government-sanctioned civilian scientific and technical committee that advises the Office of the Secretary of Defense, dubbed its notional future integrated air defense network as Strategic Aerospace Guard Environment II (SAGE II). This was a direct reference to the SAGE network that was used to help defend the skies over the United States and Canada during the Cold War.

Bringing up SAGE highlights one of the key hurdles that the Air Force and the rest of the U.S. military will need to address, which is cost. A general consensus has already emerged that trying to establish a modern version of a Cold War-esque domestic air defense network and directly protect all critical military and civilian infrastructure with kinetic defenses would be prohibitively expensive.

“Probably the third rail for homeland cruise missile defense has been the cost,” the first senior defense official said according to today’s report from Inside Defense. “Every time you start figuring out what you’re going to have to deploy to do this the way we traditionally do air defense, it is an extremely costly proposition. So, our challenge is going to be: How do we do this smartly, right-size this thing where we provide the requirements… while not necessarily looking like you are redeploying Nike batteries.”

Nike here refers to a family of Cold War-era surface-to-air missile systems that were deployed at locations across the United States, as well as to protect American facilities overseas. Nike systems were in use domestically between 1953 and 1979, and the network eventually grew to encompass nearly 300 individual sites.

“Simply put: We cannot defend everything,” U.S. Army Lt. Gen. A. C. Roper, Deputy Commander of U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) and the Vice Commander of NORAD’s U.S. component, said bluntly at an event hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) think tank last year. “Placing a Patriot or THAAD [Terminal High Altitude Area Defense] battery on every street corner is both infeasible and unaffordable.”

In 2021, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published a report that estimated it could cost between $75 billion and $465 billion over the next 20 years, or $3.75 billion to $23.25 billion annually, to acquire and operate various tiers of new and expanded air defense capabilities to help protect the contiguous United States, as well as various outlying areas. For comparison, the U.S. military is asking for $29.8 billion, in total, across all the services and MDA, for “missile defeat and defense (MDD) capabilities” in the 2024 Fiscal Year.

CBO said its “lowest cost ‘architectures'” focused on “airborne or space-based radars, surface-to-air missiles, and fighter aircraft.”

Altogether, it is not only reasonable to expect that a nuanced, flexible, and layered approach will emerge, but that this will be a necessity to provide a reasonable level of defense against cruise missiles and other aerial threats across the United States. Beyond more traditional air defense measures, including more deployable assets that can be more readily sent where they are most necessary in any given situation, other steps to try to mitigate or just get additional advance warning about incoming strikes might be taken.

“I think the future of homeland defense is vastly different than what we see today,” NORTHCOM and NORAD head VanHerck told members of Congress in March. “It is likely including autonomous platforms, airborne and maritime platforms, unmanned platforms with domain awareness sensors, and effectors that are kinetic and non-kinetic.”

“I see the future likely being much less kinetic,” he added. “There will be some areas that we should defend kinetically that could bring us to our knees, but also non-kinetic such as deception, denial, and the use of the electromagnetic spectrum.”

VanHerck also famously acknowledged what he described as a “domain awareness gap” with regard to defending the airspace over North America as a Chinese spy balloon passed over parts of the United States and Canada earlier this year. That balloon, as well as three other still unidentified objects, were subsequently shot down in U.S. and Canadian airspace. Immediate measures, including changing the sensitivity parameters on domestic air defense radars, were taken, but significant questions remain about the policies and procedures in place at the time.

The NORAD/NORTHCOM chief has been a particular advocate for additional sensor capacity, including new over-the-horizon radars to provide additional early warning against various types of threats. His mention in March of deception and denial also reflects a broader trend, particularly within the Air Force, to find novel ways to help reduce vulnerability to stand-off strikes, especially in the context of a potential future high-end conflict against China.

Cruise missile defense of critical domestic infrastructure, of course, remains a major specific source of concern. Finding the right mixture of capabilities, and ones that can be acquired and fielded at a reasonable cost in the next five to 10 years, to meet this challenge is the key reason the Air Force is conducting its new homeland air defense analysis of alternatives study.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com