A string of shootdowns of high-flying aerial objects over the United States and Canada last month has called new attention to the value of balloons for intelligence-gathering and other military purposes. This also includes acting as launch platforms for drones, potentially in large numbers, that could then be operated as networked swarms. The ability to deploy uncrewed aircraft from high-altitude balloons is real and is something that researchers around the world, including in China, have been publicly experimenting with for years now.

The idea of balloons as tools for intelligence agencies and military forces was thrust back into the public eye at the beginning of February after the U.S. government announced that it had been tracking what it assessed to be a Chinese spy balloon inside U.S. and Canadian airspace. That balloon was subsequently shot down on February 4 and efforts to retrieve the wreckage for further analysis have wrapped up.

This was followed by shootdowns of three more still-unidentified objects over U.S. territorial waters off the northeastern coast of Alaska, Canada’s Yukon territory, and Lake Huron, on February 10, 11, and 12, respectively. American officials say they increasingly believe those objects, significant remains of which have not been recovered and may never be, were benign, although they have presented no evidence to support these claims. However, this underscores the complex nature of the potential threat that high-altitude balloons, as well as other uncrewed platforms, present. Last month, President Joe Biden pledged significant changes to how the U.S. government responds to these sorts of incidents and to how these objects will be allowed to operate in U.S. airspace.

An old technology made new again

For years, The War Zone has been calling attention to the utility of balloons, airships, and other lighter-than-air craft to modern military forces for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions – something that is really not new – among other things. The Chinese government’s interest in these kinds of capabilities is well established, as you can read about more in this past feature of ours.

Beyond ISR, there have been multiple documented instances in China of balloons and other lighter-than-air craft being used to launch various things, such as test articles in support of work on unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle designs. You can read all about this revelation here. This also includes using high-altitude balloons to deploy uncrewed aircraft ostensibly as part of scientific research efforts.

Launching drones from high-altitude balloons

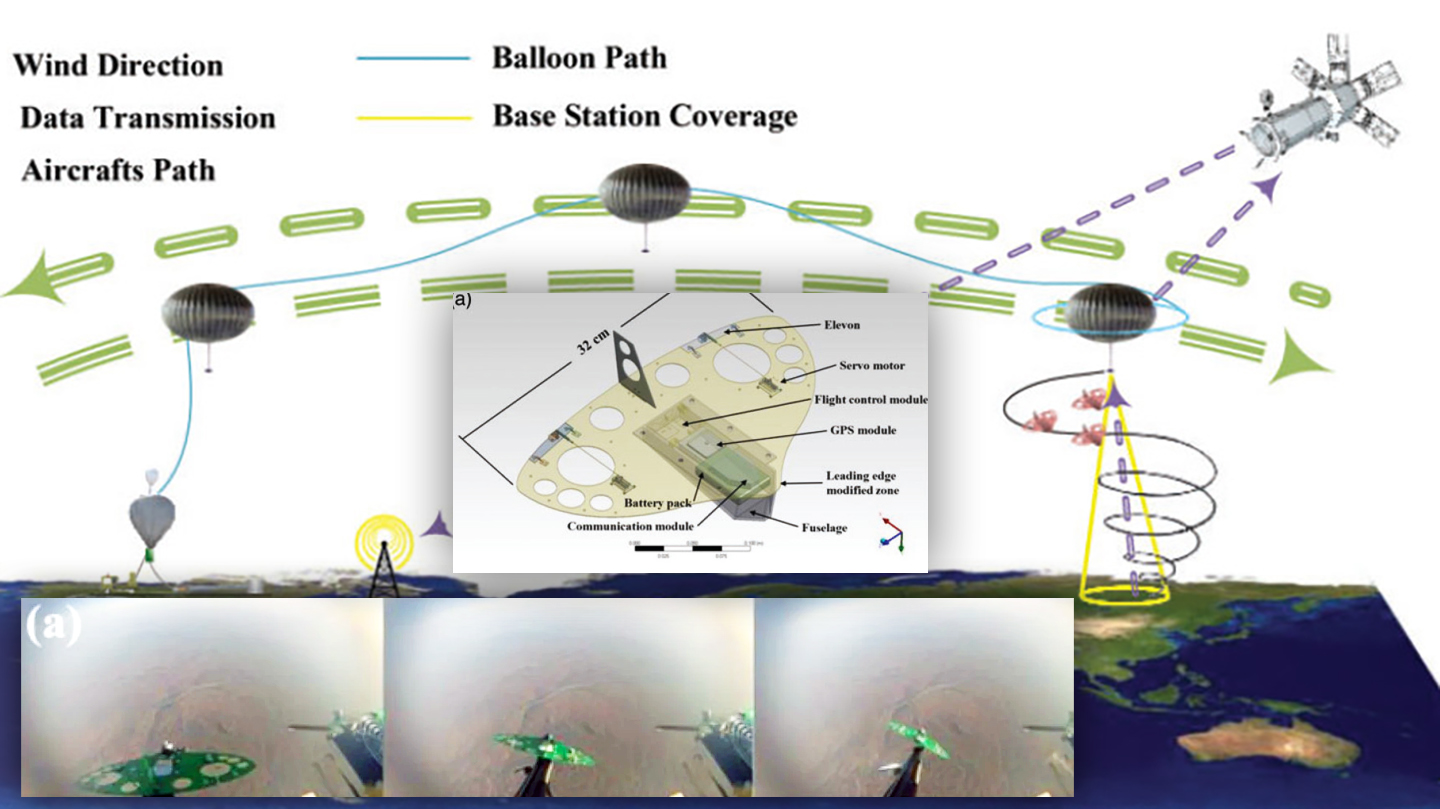

At least two uncrewed aircraft, which appear to have been unpowered glider-like designs, were launched from a stratospheric balloon during testing in China’s Inner Mongolia region in September 2017. One was deployed at an altitude of approximately 25 kilometers (nearly 82,021 feet), while the other was released from a height of around nine kilometers (some 29,527.5 feet), according to a subsequent story from the South China Morning Post (SCMP) newspaper in Hong Kong. Subsequent information from other Chinese sources says the releases were actually from 10 and 20 kilometers, or just over 32,808 and nearly 65,617 feet, respectively.

The 2017 SCMP story described the drones as being made primarily from composite materials. It further said that they were “about the size of a bat” and “small enough to fit in a shoebox and weigh about the same as a soccer ball.” They appeared to use printed circuit boards (PCB) for their core construction based on the images available

“The drones then glided towards their targets… adjusting course and altitude in flight without human intervention,” according to SCMP. “On-board sensors,” including “a terrain mapping device and electromagnetic signal detector,” then “beamed data back to a ground station.”

“The drones would not carry cameras… as the transmission of photo or video data over long distances requires bulky antenna unsuitable for near space launches,” according to the piece.

SCMP also interestingly reported that the bat-sized drones were launched via an electromagnetic accelerator of some kind to get them up to a speed of around 100 kilometers per hour (just over 62 miles per hour) “within a space about the length of an arm.” This method was apparently chosen due to concerns about employing systems utilizing electric initiation in the near-vacuum-like conditions in the upper stratosphere.

“One of the biggest headaches is the near-vacuum environment, where electric currents can produce a spark,” Yang Chunxin, a professor at the School of Aeronautic Science and Engineering at Beihang University in Beijing, told SCMP at the time. “This can lead to shortages and damage electronic equipment.”

The balloon that carried the drones aloft, seen in the picture below, had an envelope with a total volume of around 7,000 cubic meters (close to 247,203 cubic feet), a maximum payload capacity of 150 kilograms (nearly 331 pounds), and stayed aloft for eight hours in total, according to a release from China’s Aerospace Information Research Institute, which is part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The Academy of Optoelectronics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing was principally responsible for the design of the balloon and the drones.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences cited those tests in Inner Mongolia, among others, in an academic paper in 2020 that proposed an evolution of this general concept. A heavy focus of that research was on developing a very low-cost “micro glider” that could “be launched from a super pressure balloon at high altitude, glide to the target position to collect data and upload data to the staying balloon.”

Like the ones tested in 2017, the proposed glider would be fabricated primarily from a PCB. It would be fitted with a limited number of unspecified sensors, as well as other systems, including a GPS receiver and an inertial measurement unit (IMU) for navigation purposes. It’s not immediately clear how many examples of this design may have been fabricated and if they were flight tested in any context.

Interest in and work on concepts for launching drones from balloons and other lighter-than-air craft is, of course, not limited to Chinese academic institutions. In the introduction to their 2020 academic paper, the researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences specifically cited prior demonstrations of similar capabilities by teams in the United States, Germany, and Switzerland dating back to 2011. The use of balloon-launched drones in all of these instances was in support of weather and other scientific research experiments.

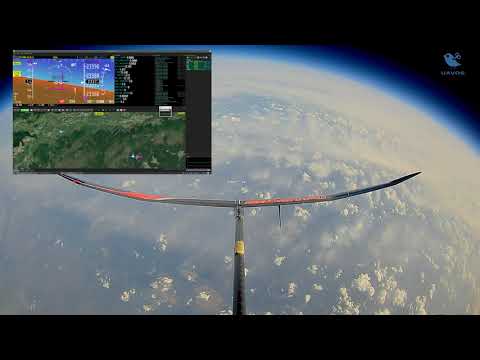

The designs cited in the paper include ones that are significantly bigger and otherwise more capable in terms of performance and payload than the Chinese PCB-based drones. A prime example of this is HiDRON, a balloon-deployed unpowered high-altitude glider-type drone developed jointly by U.S.-based company UAVOS, Inc. and a firm headquartered in Canada called Stratodynamics.

HiDRON was first flight tested in 2018 and is designed to be recoverable via parachute at the end of its flight. It has since demonstrated its ability to successfully soar back to the ground after being released from balloons at altitudes up to 34 kilometers (approximately 111,400 feet).

The drone has a modular payload bay that can carry sensors and other systems weighing up to a total of five kilograms (around 11 pounds) and can send data back to individuals on the ground while in flight via either a line-of-sight system or an Iridium satellite link, according to Stratodynamics’ website. It’s not immediately clear how far HiDRON drones may be able to travel laterally from its launch point, but it is capable of gliding horizontally and the radio telemetry link has a stated range of 100 kilometers (just over 62 miles).

The military dimension

There is, of course, clear potential military value in being able to launch drones, and potentially large swarms of them, from high-altitude balloons. This reality has not been lost on Chinese researchers, as well as researchers from other countries.

“Whether they can play a practical role in military operations remains an open question,” Beihang University’s Professor Yang told SCMP in 2017, citing technical hurdles in creating suitable uncrewed aircraft capable of being deployed in the stratosphere.

It’s worth pointing out here that Beihang University’s broader work on high-altitude lighter-than-air craft, including solar-powered dirigible-like types, with clear potential military applications, is well-established, as you can read more about in this past War Zone feature. Last month, The New York Times published a detailed piece centered on another researcher at that institution, Wu Zhe.

That story explored his work and direct links to at least three of the six companies the U.S. government has now sanctioned over their ties to the Chinese government’s high-altitude balloon surveillance program.

In addition, in 2017, SCMP reported that Yang Yanchu, the researcher at the Academy of Optoelectronics who led the tests over Inner Mongolia, specifically said the sensors on the experimental drones that had been test-launched were capable of being used to “locate military presence or activities.” In addition, he explained to the outlet that “the goal of our research is to launch hundreds of these drones in one shot, like letting loose a bee or ant colony.”

“The innovative application of the balloon system and micro air vehicles [MAV] proposed by our group provides a possibility for the MAV to execute long-endurance long-distance scientific or military missions,” the 2020 paper from researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences also says bluntly.

It would not be hard to imagine that what we know about ostensibly scientific-focused work on balloon-launched drones in China offers just a glimpse of what is also being done in the country on the military side. In general, the lines separating work done at Chinese scientific organizations and commercial enterprises engaged in advanced aerospace work, among many other things, and the country’s military research and development efforts are very often, at best, blurred.

Chinese scientific, commercial, and military entities are not the only ones with interest in high-altitude balloons or the ability to launch drones from them, either. In their 2020 paper, the Chinese Academy of Sciences researchers say their proposed concept was directly inspired in part by work the U.S. Navy’s Naval Research Laboratory conducted as part of its Close-in Covert Autonomous Disposable Aircraft (CICADA) project.

Like the Chinese proposal, CICADA involved unpowered glide-like micro drones made in large part from circuit boards with GPS-assisted navigation capabilities and the ability to carry small sensors. The Navy conducted a slew of tests of multiple CICADA designs between 2010 and 2020. Launches of CICADAs, in small numbers and in swarms of up to 1,000 drones, from various platforms, including crewed and uncrewed aircraft, were part of this overall effort. In at least one test carried out in the early 2020s, CICADAs were deployed from another drone, called Tempest, which had itself been first released from a high-altitude balloon.

The exact current state of the CICADA effort is unclear, but the U.S. military’s interest both in low-cost drone swarms and the potential to deploy them from various aerial platforms, including high-flying balloons, has not diminished. Experimentation with these kinds of capabilities within the U.S. military extends beyond the Navy, too.

Perdix, a project that the Pentagon’s Strategic Capabilities Office ran between 2014 and 2016, which included cooperation with the Navy, saw the development of another micro-drone similar in some general respects to CICADA. However, the Perdix drone was powered using a small electric motor to drive a pusher propeller. Demonstrations showed that crewed aircraft, operating at much lower altitudes than a stratospheric balloon, could deploy swarms of dozens, if not more, of these drones at a time. These swarms could be controlled as a cooperative team.

In 2021, the Pentagon announced that its Joint Capability Technology Demonstration (JCTD) program office had turned over various uncrewed swarming technology research and development efforts, or parts thereof, to the U.S. Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. All of the projects centered on various means of employing versions of Raytheon’s Coyote drone in swarms, including air-launched and sea and ground-based concepts.

At that time, the Navy had already experimented with the original Coyote design through a program called Low-Cost UAV Swarming Technology (LOCUST). Subsequent Coyote variants have been developed that can be configured as loitering munitions or anti-drone interceptors, among other things.

The U.S. Army has also been exploring concepts specifically centered on using high-altitude balloons to deploy a variety of payloads over the battlefield, including deep inside enemy-controlled territory. The service has specifically described how balloons could be used to disperse unattended ground sensors and drones of various types in highly contested areas. Unattended ground sensors are typically emplaced discreetly to help monitor enemy force movements and other activities. When it comes to drones, the Army’s plans include discussions about larger and otherwise more capable designs than the Chinese PCB-based microdrones or the Navy’s CICADA concept that could be employed as loitering munitions, as you can read more about here.

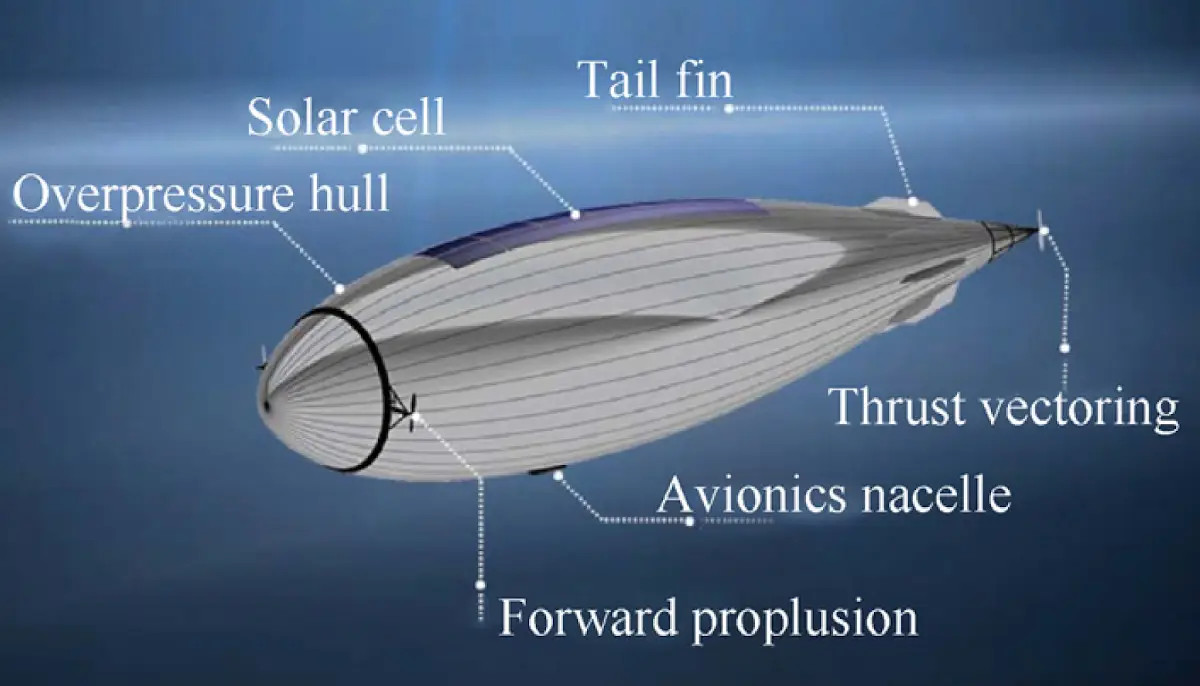

The Army has a broader vision for how it might use lighter-than-air craft in future conflicts that would involve them performing other tasks, including acting as surveillance and communication nodes. The Navy has been experimenting with balloons, such as Raven Aerostar’s Thunderhead, in this latter role, as well. Other companies, like the Sierra Nevada Corporation, with its Lighter-Than-Air High-Altitude Platform Station (LTA-HAPS), are pitching similar capabilities to the U.S. military and others.

Just what can balloon-launched drones do?

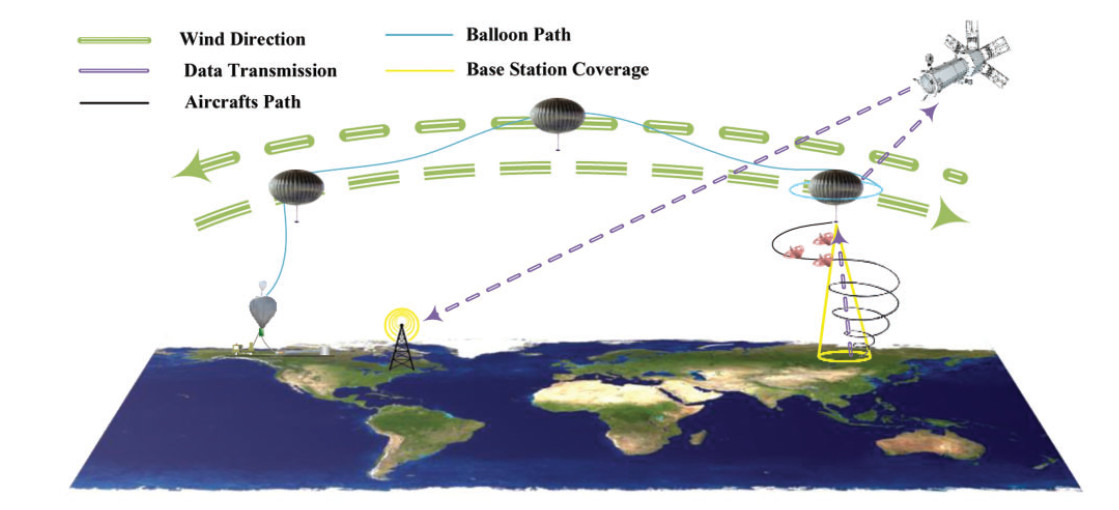

Whether employed by the Chinese or U.S. armed forces, or any other actor, balloons loaded with swarms of drones could offer significant advantages over other systems for carrying out ISR and other missions. At their core, modern high-altitude balloons and airships offer platforms that can navigate and maneuver across long distances to designated target areas. Once there, they are then capable of persistently holding station against prevailing winds.

The Pentagon has previously said specifically that the Chinese spy balloon shot down off the coast of South Carolina in February had the ability to maneuver. A high-resolution image of the balloon that the U.S. military subsequently released shows that its payload included what appears to be four sets of propellers.

Another similar high-flying balloon spotted flying over Japan in 2020, which authorities in that country now believe is likely linked to a broader Chinese high-altitude surveillance program, had very visible propellers, as you can see in the video below.

Drones, even very small unpowered types, launched from these altitudes have the potential to travel great distances themselves. This could allow the balloon or airship acting as the launch platform to either stay further away from the actual area of interest, helping to reduce the potential for detection, or try to reach targets deeper inside enemy territory. This latter point in particular, as has already been noted, is a general capability that the U.S. Army has publicly expressed explicit interest in and one that Chinese researchers have at least alluded to.

As the incidents in the airspace over the United States and Canada in February further highlighted, lighter-than-air craft can be difficult to spot and track on radar, to begin with.

In the two Chinese tests over Inner Mongolia in 2017, the intended targets were reportedly 100 kilometers (just over 62 miles) away. However, in both instances, the drones had difficulty maintaining stability and traveled only 3.3 kilometers (around 2 miles) and 15.8 kilometers (just over 9.8 miles) after being launched at their respective altitudes (nine kilometers/~29,527.5 feet and 25 kilometers/~82,021 feet), according to the 2020 Chinese Academy of Sciences research paper.

The Navy separately demonstrated the ability of CICADA drones to glide up to 11 miles away from a launch platform flying at just 18,000 feet.

If a balloon could indeed carry drones able to fly 100 kilometers (62 miles) away from the launch point, they would be able to reach any location within a circle around that point covering approximately 31,416 square kilometers (around 12,130 square miles).

The drones could be programmed to try to fly to a designated point for recovery on the ground or be designed to be expendable. Depending on the sensors and other systems installed, they could potentially relay useful information back to command and control nodes in near-real-time via various means. The launching balloon could serve as an immediate relay point, receiving data from the drone and forwarding it on via a satellite link.

Additional types of networks, including mesh-type ones utilizing a constellation of other high-altitude balloons, drones, and/or other platforms, could be utilized, too. High-altitude balloons, in general, make excellent platforms for communications and data-sharing systems given the excellent lines of sight they provide for those links.

Even without the ability to carry cameras or other imagery-gathering sensors, the drones could collect various kinds of useful intelligence while flying along those paths. Just being able to scoop up data on electromagnetic signals in the area, and where they are coming from, could help the process of establishing a so-called electronic order of battle of an opponent’s radars, communications nodes, and other emitters, and their dispositions. Just locating relatively benign signals could even be key in locating enemy forces.

A fully-networked swarm of drones could be used to gather such intelligence more effectively and efficiently across a broader area in a shorter amount of time, as well.

Intelligence-gathering is just one potential role for balloon-launched drones. Loaded with small electronic warfare jammers, or even just fitted with radar reflectors to act as decoys, they could overwhelm or confuse enemy air defenders. This, in turn, might help mask friendly assets or otherwise draw an opponent’s attention away from real threats, or simply make it difficult for them to respond effectively.

There are already precedents for using balloons carrying radar reflectors themselves to help gather intelligence about enemy air defense capabilities by stimulating them and even prompting them to waste valuable time and resources. The Russians have just recently been employing such tactics in Ukraine.

Depending on their exact size and capabilities, drones deployed from high-altitude balloons could perform other tasks, too, including direct strikes on targets down below. A swarm of them would be able to target enemy assets across a broad area. They could be used to quickly destroy key capabilities, or at least disable them temporarily, such as air defense networks, by targeting fragile things like radar dishes or antenna arrays that can be honed in on by their RF energy. You could imagine a balloon with the ability to locate electronic emissions from threat air defense systems from on high, then releasing drones to go home in on those emissions and attack them, all from behind or very near enemy lines.

Even drones only capable of carrying relatively small warheads could be used to inflict significant damage to military logistics nodes, such as ammunition and fuel dumps by triggering secondary explosions. On top of all this, they could just harass enemy forces, upending their decision-making cycles, keeping them on edge, and degrading morale.

With certain payloads, drones that ostensibly crash inside hostile territory might actually be able to perform useful functions. They could effectively turn into ground-based sensors or electronic warfare jammers, or even small land mines, for instance. One of the explicit ideas behind the U.S. Navy’s CICADA program was exploring a capability “to ‘seed’ an area with miniature electronic payloads.” As mentioned earlier, the Army’s plans have included balloon-deployed unattended ground sensors, too.

The coming swarm

One of the inherent benefits a fully networked swarm offers is that each drone within it can be configured to perform just one mission, with the entire group then being able to carry out multiple tasks simultaneously. As such, a swarm released from a high-altitude balloon could be tasked to perform a mix of the aforementioned mission sets in order to achieve a common overall goal.

Chinese companies, in particular, have made significant strides in recent years in the development of relevant control architectures for operating and managing swarms made up of drones with high degrees of autonomy. For instance, the two videos below show ground control systems being used to quickly assign and reassign sub-groups of drones from a larger swarm to conduct tasks in multiple zones across a broad area simultaneously.

Both clips are directly associated with a ground-based launcher capable of deploying swarms of loitering munitions produced by the state-run China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC), which The War Zone has profiled in the past. A swarm launcher similar to the one seen on the truck-based system could potentially be adapted for use suspended from a high-altitude balloon.

Swarms made up of expendable drones present additional issues for a defender in terms of cost calculus. The reality has been notably exposed by the experiences in recent years of the Suadi Arabian armed forces in their efforts to intercept and shoot down drones launched by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in neighboring Yemen. Even without employing drones in networked swarms, the Houthis have been able to gobble up significant Saudi air defense resources that come at a high cost and long lead time.

This was also highlighted, in a way, by the incidents last month in U.S. and Canadian airspace. The Chinese spy balloon and each of the other three objects that were brought down by AIM-9X Sidewinder missiles, each of which costs around $450,000, fired from fighter jets that cost tens of thousands of dollars per hour to operate. A second missile was needed to bring down the object over Lake Huron, as well.

Had the balloon or other objects released drones, it would have required even more resources to try to neutralize or otherwise contain them, if they could even be spotted and tracked at all. A large number of balloons or other lighter-than-air platforms carrying swarms deployed at once would only magnify these issues without a significant increase in costs for whoever might be employing them.

This isn’t even taking into account the costly sensor networks needed to spot, categorize, and track these potential threats. We know that the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) needed to tweak the settings on its radars just to detect the other three objects and that doing so created a glut of additional data that needed to be sifted through, presenting the increased potential for false positives and other issues.

In general, drone swarms employed in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance roles, among others, are set to become a defining feature on future battlefields. There are likely to be especially critical for combatants engaged in major, high-end conflicts, such as a potential one between the United States in China in the Pacific region. Wargames focused on various Taiwan crisis scenarios, including tabletop exercises conducted under the auspices of the U.S. military, have repeatedly highlighted how swarms could be game-changing in that specific context, as you can read more about here.

How best to deliver those swarms of smaller drones to a battlefield area remains an open question. With that in mind then, it’s not surprising at all that the Chinese military, as well as the U.S. military and others, would be interested in what balloons have to offer as a delivery system for such capabilities. They are by their very nature low risk, hard to detect and shoot down, and can travel over long distances to deliver their payloads. While developments over the past decade or so have highlighted technical hurdles to overcome, such as ensuring drones remain stable after launch at very high altitudes, they have also demonstrated very real capabilities.

All told, the idea of using high-altitude balloons for intelligence-gathering and other military roles is clearly in the midst of a renaissance of sorts in China, as well as the United States and other countries. The shootdown of the Chinese spy balloon in U.S. territorial waters off the coast of South Carolina last month only underscores that these capabilities are being actively used now. On top of this, it has shone a new light on the extensive work that the U.S. military, among others, has also been doing in this arena.

With all this in mind, high-altitude balloons look set to become more commonly employed to perform various military missions. This potentially includes launching drones, a capability that Chinese groups and others have already demonstrated to varying degrees.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com