China has surpassed the United States in the number of land-based intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) launchers it possesses. The assessment comes amid growing concerns over China’s efforts to rapidly expand its nuclear arsenal. On top of that, relations between the U.S. and China are at a particularly low point after a surveillance balloon belonging to Beijing was discovered in American airspace last week.

The data about Chinese ICBM launchers came in a brief letter to the House and Senate Armed Services Committees authored by U.S. Air Force Gen. Anthony J. Cotton, commander of the U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM), dated Jan. 26, 2023. Notifications like Cotton’s are now required under legislation passed last year that necessitates STRATCOM alert Congress if China is to surpass the U.S. in ICBM silo, missile, or warhead inventory in an effort to better keep tabs on the nation’s strategic expansion.

However, Cotton also noted in the letter that the U.S. military still does surmount China in the number of actual ICBMs and nuclear warheads to equip said missiles that it possesses.

While the STRATCOM notice doesn’t elaborate, experts told The Wall Street Journal (WSJ), which was among the first outlets to report on the assessment, that the launcher increase likely has to do with China’s new silo construction blitz. Readers of The War Zone can learn about it in detail in this past report, but the shorthand version is that China has been making significant progress in constructing silo fields to house their ICBM launchers as of late.

In 2021, satellite imagery that had been obtained by The New York Times showed China’s construction efforts for one of what is now known to be three solid-fueled ICBM silo fields. Matt Korda and Hans Kristensen from the Federation of American Scientists who first spotted the development dubbed it “the most significant expansion of the Chinese nuclear arsenal ever.”

The Pentagon estimates that China currently has approximately 300 total ICBMs in its rocket force, including those used by both fixed and mobile launchers.

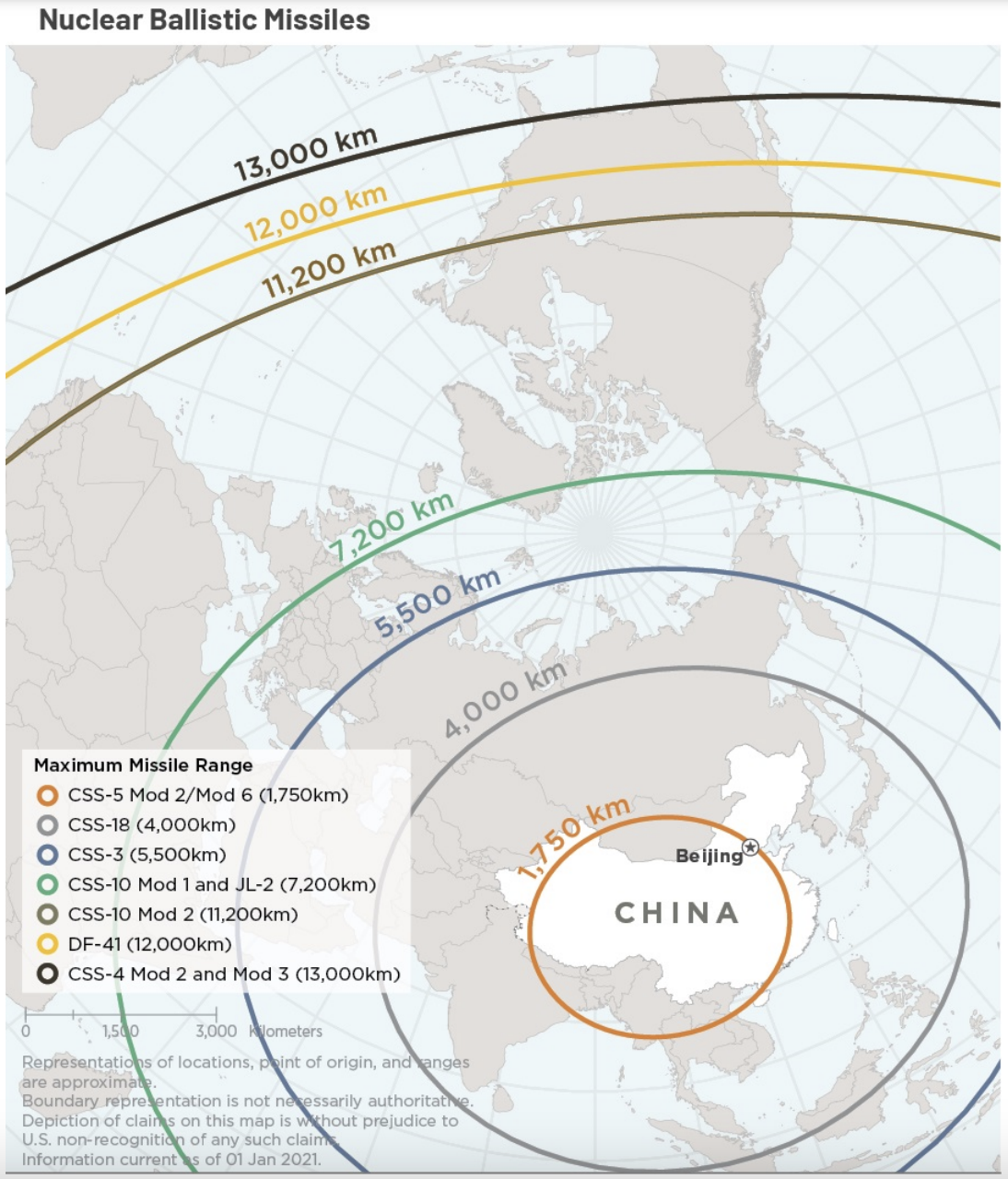

Four main ballistic missile types are currently known to be in Chinese inventory. DF-4 entered service in 1980 and is a transportable, liquid-fueled missile with a single nuclear warhead and a range of up to 3,417 miles. DF-5 is a silo-based liquid-fueled ICBM that entered service in 1981 and has a range of around 8,077 miles. A DF-5A variant carries a single warhead while DF-5B carries multiple independently targeted warheads, and the Pentagon believes a DF-5C is now in development as well.

Third on the list is DF-31, a solid-fueled missile that entered service in 2006, which carries a single warhead, and has a range of up to 7,270 miles. The final missile is DF-41, a road-mobile ICBM that was first tested in 2012 but has yet to officially enter operational service despite the country having already explored a train-based launch system for the missile. DF-41 is solid-fueled, can carry up to 10 warheads, and has a range of about 9,320 miles.

The PLA Rocket Force’s (PLARF) road-mobile launcher inventory has undoubtedly been increasing with the introduction of the DF-41, but the bulk of the launcher increase outlined in the STRATCOM notice comes from China’s silo construction.

According to the Pentagon’s 2022 China Military Power Report (CMPR), China’s silo fields will cumulatively contain at least 300 new ICBM silos. This project “intends to increase the peacetime readiness of its nuclear force by moving to a launch-on-warning (LOW) posture,” read the CMPR. LOW posture is a military strategy that allows for the retaliatory launch of a nuclear weapon in response to the detection of an incoming enemy strike.

The CMPR goes on to state that China’s silo fields are likely capable of fielding both DF-31 and DF-41 ICBM types. The Pentagon believes that improved variants of both types are in the works with the People’s Republic of China.

The CMPR also adds that China is building more silos for its liquid-fueled DF-5 class ICBMs. To support the additional silos, the Pentagon said that the PLARF will be “increasing the number of brigades while simultaneously increasing the number of launchers per brigade – though there is currently no indication this project will approach the size or numbers of the solid-propellant missile silos.”

If China is to maintain the momentum it has built up throughout its recent nuclear expansion efforts, the CMPR predicts that the country “will likely field a stockpile of about 1,500 warheads” by 2035. This is the year China is aiming to complete the overall modernization of its national defense and armed forces.

Regardless, it remains unclear whether or not Beijing actually plans to fill the entirety of its silo fields with nuclear-armed ICBMs as the goals of its military overhaul are realized over the next decade. Ways that the U.S. could potentially control this outcome could be by agreeing upon more restrictive arms control legislation with China. An example of this would be the New START Treaty between the U.S. and Russia, which caps out the number of nuclear warheads and bombs both countries can deploy at 1,550 among other regulations. It is set to expire in 2026.

While the Trump administration did attempt to convince China to join a New START follow-on once the initial treaty sunsets, the country has rejected these propositions. Even if China were to have a change of heart in this regard, the U.S. would need to be prepared to “clearly articulate what it is willing to trade in return for limits on Chinese forces,” the Federation of American Scientists has argued in the past.

China isn’t projected to even get close to the U.S. and Russia’s New START limit of having 1,550 nuclear warheads deployed until 2035, meaning it will have been operating well under that cap before then. With China’s nuclear arsenal already being notably smaller than that of Russia’s and the U.S., any discussions aimed at bringing China onto the New START agreement would likely consist of some significant trade-offs between the three powers.

That isn’t to say that China’s growing nuclear arsenal shouldn’t still be a cause for concern. If it is to eventually fill its 300 new silos with its ICBMs, the move would only add to the hundreds of other existing ballistic missiles in the PLARF’s arsenal that are not silo-based. With the U.S. itself having 400 ICBMs, all silo-based, if China decided to fill all of its new silos with missiles it could put the country at a numerical superiority over the U.S.

However, experts have already raised the possibility that China may ultimately decide not to fill all of the silos. This encapsulates a tactic commonly called the ‘shell game,’ which is when a significant number of silos are built but fewer of them are actually loaded with ICBMs. Missiles can be moved around and different silos can be activated at different times to help complicate enemy targeting. This makes it so enemies have to question where the actual missiles are housed, leaving them with no choice but to exhaust their resources by targeting every single silo in any potential effort to destroy them.

It’s also important to note that one-for-one ICBM counting doesn’t take into account other strategic capabilities the U.S. currently has more of than China. Indeed, the U.S. is still ahead of China in terms of submarine-launched ballistic missiles and long-range bombers. However, as exemplified by the new silo fields, China is actively working to increase the number of strategic capabilities that make up what is morphing into a real nuclear triad. This includes more of its own nuclear ballistic missile submarines and potentially nuclear-armed bombers, not to mention the possibility of further developing non-traditional nuclear delivery systems, like its exotic nuclear-capable hypersonic weapon that can orbit the Earth.

In 2020, China most notably “operationally fielded the H-6N bomber, providing a platform for the air component of the PRC’s nascent nuclear triad,” the CMPR read. The H-6N is a derivative of the H-6K that has been optimized for long-range standoff strikes. H-6N features a modified fuselage that allows it to externally carry a nuclear-capable air-launched ballistic missile. The H-20 strategic stealth bomber is also in development, and Chinese state television has noted that the aircraft will serve both nuclear and conventional missions.

Other bomber development programs are expected to be in the works as well, with the CMPR noting that the Chinese Air Force “is also developing new medium- and long-range stealth bombers to strike regional and global targets. PLAAF leaders publicly announced the program in 2016, however, it may take more than a decade to develop this type of advanced bomber.”

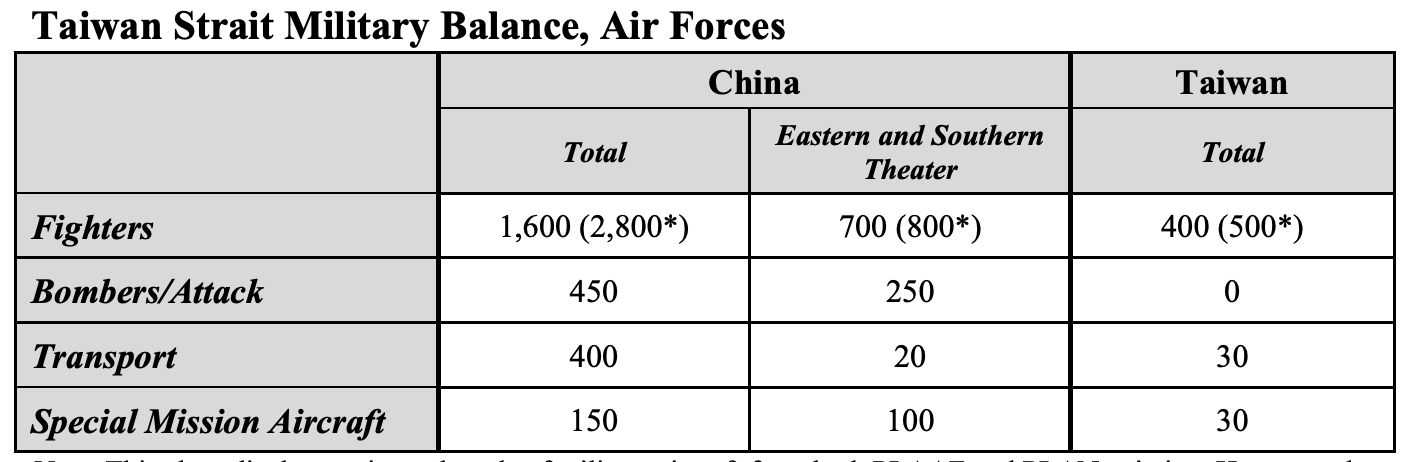

All told, these advancements also echo just how rapidly China has been fielding and how heavily it has been investing in high-end military technologies. Whether it be strategic nuclear weapons or conventional systems like next-generation fighter jets, advanced drone concepts, and a massively expanded naval arm, China’s military is evolving at an increasing pace.

As China pushes to balloon its nuclear arsenal and the credibility of its deterrent overall, it’s possible that a major driver behind it may be to make it more difficult for the U.S. to intervene during a Chinese operation to seize territory, or especially to invade Taiwan. Developing and deploying a much larger and more diverse nuclear arsenal would certainly up the risk for various levels of intervention by the U.S. With indications that this type of operation could occur sooner than anticipated, it would definitely fit with Beijing’s rush to expand its strategic forces.

“As I assess our level of deterrence against China, the ship is slowly sinking,” said Navy Adm. Charles A. Richard at last year’s Naval Submarine League Annual Symposium & Industry Update’s Awards Luncheon. “It is sinking slowly, but it is sinking, as fundamentally [China is] putting capability in the field faster than we are. As those curves keep going, it isn’t going to matter how good our [operating plan] is or how good our commanders are, or how good our horses are — we’re not going to have enough of them. And that is a very near-term problem.”

This period in time has been a low point for U.S.-China relations because of various issues, prominently including territory disputes over Taiwan. Additionally, last week, a Chinese surveillance balloon took the news cycle by storm after initially being spotted hovering over Montana. The balloon has since been shot down and recovered by U.S. forces, but only after violating American airspace for several days.

The incident led Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, who was expected to travel to Beijing soon, to cancel his trip, squandering what many had seen as a likely opportunity for rapprochement. Thus, while the exact significance of China’s increase in ICBM launchers is being debated, it certainly only adds to the burgeoning geopolitical friction between the two countries.

Contact the author: emma@thewarzone.com