The U.S. military is concerned that China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) may be looking to develop and field a conventionally armed intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). This could offer Chinese forces a means to strike targets across the continental United States, as well as Hawaii and Alaska, without having to resort to nuclear weapons.

Key aims here would be to field an important conventional deterrent capability that could hold targets across the United States at risk while also reducing the likelihood of nuclear retaliation. This capability would also create new worrisome strategic ambiguity and uncertainty to contend with that could be to China’s benefit, as well as be potentially dangerously destabilizing.

The Pentagon highlighted that the PLA may be exploring a conventional ICBM in its latest annual report to Congress on Chinese defense and security developments, an unclassified version of which it released today. The report also provides new information about the Chinese military’s ongoing efforts to significantly expand its nuclear deterrent capabilities.

The U.S. military now estimates China has at least 500 nuclear warheads, up from 400 last year. It could be on track to have as many as 1,500 by 2035. It also states that its nuclear weapons production levels look to exceed previous assessments. U.S. officials increasingly view China’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal as an effort to move closer to direct parity with the United States, if not eclipse it in certain regards.

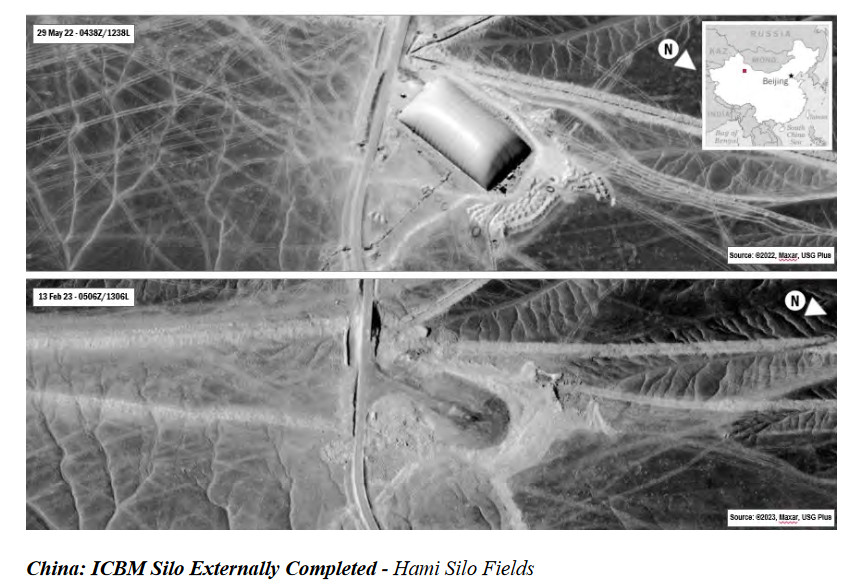

The PLA has a number of new and improved nuclear-armed ICBMs in various stages of development and/or fielding, including the DF-5C, which the Pentagon says could be armed with large warheads with multi-megaton yields. Existing DF-31 ICBMs may now also be loaded into some of the large number of silos that the Chinese have been building in recent years.

The PLA may now be looking to deploy ICBMs with conventional warheads.

“I think what I would say is just to put it in a little bit of broader context, you know, the PLA rocket corps when it introduced conventional missile capabilities, now more than 20 years ago, started with short-range ballistic missiles,” a senior U.S. defense official told The War Zone and other outlets during a press briefing ahead of the report’s release yesterday. “They expanded over time to include medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles and their conventional force. And now we see them kind of continuing to follow that progression and we see now possible interest in development of a conventional ICBM.”

It should be pointed out that, while the senior U.S. defense official specifically discussed the possibility of a conventionally-armed Chinese ICBM, the Pentagon report that was released today talks more generally about “conventionally-armed intercontinental range missile systems.” Though an ICBM-type design would be the most obvious missile system for carrying out strikes at these ranges, there are other options.

China has, for instance, demonstrated a fractional orbital bombardment system with a worldwide range that utilizes a hypersonic boost-glide vehicle launched via an ICBM-sized rocket booster, which you can read more about here. This system, which the U.S. has said in the past represents a viable operational capability, could be armed with a conventional payload.

A nuclear-powered, but conventionally armed cruise missile, akin to the nuclear-tipped Burevestnik that Russia claims to have successfully tested recently, is another ‘exotic’ possibility.

Regardless, “what we would highlight about that is it would give them a conventional capability to strike the U.S. for the first time for the PLA Rocket Force [PLARF], and to, you know, of course, to threaten targets in the continental U.S., Hawaii, and Alaska,” the senior U.S. defense official added yesterday. “And I think, you know, as we see them maybe exploring the development of those conventionally-armed ICBMs, it raises some questions about risks to strategic stability.”

It’s also worth highlighting here that the PLA Air Force (PLAAF) also currently lacks the ability to strike the contiguous United States. This speaks directly to the continued limits of its current bomber force, which only gained an air-to-air refuelable nuclear-capable type with the fielding of the H-6N in 2019. The H-20 stealth bomber that is understood to be in development now, paired with a very long-range survivable cruise missile, may change this calculus. However, it is unclear when that aircraft might actually enter service.

The PLA Navy is similarly still in the process of establishing a truly robust capacity to deploy larger surface warships and missile-armed submarines well away from the mainland on a constant basis that can launch conventional strikes deep ashore.

This all puts further emphasis on the PLA Rocket Force (PLARF) as a key means for carrying out strikes of any kind on targets, especially time-sensitive ones, on the opposite side of the world from China.

The senior U.S. defense official did not elaborate yesterday on what the risks associated with this development of a strategic-focused, but conventionally-armed ICBM might be, but there are a number of obvious worrisome implications.

A likely goal of developing such a system for the PLA would be to have a weapon that puts strategic targets, such as air bases, ports, major command and control nodes, and seats of government, as well as symbolic ones, anywhere in the United States (or really anywhere in the world) at risk without having to escalate to the use of nuclear weapons. This could offer a powerful deterrent to non-nuclear strikes against the Chinese mainland.

In addition, the hope could be that if these conventional ICBMs ever had to be used the U.S. government, or any other potential nuclear-armed adversary, would be significantly less likely to retaliate with nuclear weapons.

At the same time, there could be a risk of this significantly lowering the threshold for the PLA to be willing to conduct a non-nuclear strategic strike if it believes it can escape a nuclear response. This could be doubly risky since the U.S. government has an explicit deterrence policy wherein it reserves the right to respond to non-nuclear strikes of sufficient severity with nuclear weapons.

In addition, depending on the design of any future conventional ICBM, the U.S. government may not know whether or not an incoming one is nuclear-armed or not, and would have very limited time in which to decide how to react no matter what. This is called launch on warning and a retaliation could occur before the warhead arrives on target to find out if it is conventional or not.

It is worth noting that China has long made active use of this kind of ambiguity and uncertainty as part of its deterrence strategy, typically with regard to shorter-range ballistic missiles. The DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), which is understood to have a “hot swappable” warhead section that allows it to be readily configured as a conventional or nuclear weapon as required, is a prime example.

Historically, China has done this, in part, to help offset the relatively small size of its nuclear stockpile, something that, as already noted, is now rapidly growing. That ambiguity has also long led the U.S. government to question the Chinese government’s commitment to its stated no-first-use (NFU) policy when it comes to nuclear weapons.

“The PRC’s [People’s Republic of China’s] commingling of some of its conventional and nuclear missile forces during peacetime and ambiguities in its NFU conditions could complicate deterrence and escalation management during a conflict,” the Pentagon’s new China report says. “If a comingled PRC missile launch is not readily identifiable as a conventional missile or nuclear missile, it may not be clear what the PRC launched until it detonates.”

Adding a conventionally armed ICBM to this mix can only further raise the risk of misinterpretations and miscalculations on both sides. Any increased willingness on the part of the PLA to strike at the United States with this added conventional capability could be especially dangerous.

The Chinese government has already pushed back on the new Pentagon report, as a whole.

“We firmly opposes [sic] the US side hyping up various versions of the ‘China threat’ narrative and making groundless allegations and smears towards China” Liu Pengyu, a spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., said, according to VOA‘s Jeff Seldin. “[China] is committed to a defensive nuclear strategy, keeps its nuclear capabilities at the minimum level required by national security and does not target any country … [honors] our pledge to ‘no first use’ of nuclear weapons at any time.”

However, at least when it comes to the idea of the PLA developing and fielding a conventional ICBM, this is not the first time this possibility has come up.

“The PLA’s ‘Science of Second Artillery Campaigns’ is a military publication dating from 2004 that broadly discusses how the Chinese military envisions employing its strategic missile forces in wartime,” a story published by The Diplomat in 2021 notes. “Although the document is extremely dated at this point, it still serves as one of the few publicly available sources that provides a window into how the PLA views nuclear and conventional missile strikes.”

“In the section of this publication that discusses the PLA then-Second Artillery Corps’ (now the PLA Rocket Force) participation in joint operations to “resist against intervention from the Powerful Enemy,” authors state: …carefully select long range or intercontinental missiles armed with conventional warheads to target the enemy territory and their will to fight, and at the right moment, conduct a long-range warning strike. This will cause the enemy to be unwilling to suffer unbearable attacks and limit its intervention operations.”

“The Powerful Enemy” references here is understood to be the United States.

“To be clear, the discussed evidence is entirely circumstantial and does not explicitly tie the growth in China’s ICBM force to a conventional strike mission,” the piece from The Diplomat two years ago notes. “However, there is sufficient evidence to warrant greater consideration of the possibility that China is currently or could in the future consider the use of land-based ICBMs or other strategic launch systems in a conventional role.”

This is also in line with the senior U.S. defense official’s discussion yesterday about the PLA’s trend toward ever longer-range conventional ballistic missile capabilities over the past few decades.

The U.S. military has also considered fielding conventionally-armed submarine-launched Trident ballistic missiles in the past, but ultimately abandoned the project.

The Conventional Trident Missile (CTM) “was later canceled by lawmakers because of concerns that an adversary seeing a CTM launch might think the United States was launching a nuclear-armed Trident missile and might respond with a nuclear attack of its own,” according to a January 2023 report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). “To avoid such confusion, the United States has generally maintained different types of missiles to carry nuclear warheads and conventional warheads.”

Since the CTM’s cancellation, the focus has shifted to conventionally-armed sea-launched hypersonic missiles for the U.S. Navy. The U.S. military’s stated intention to field various conventional hypersonic weapons primarily for use in strategic-level strikes against major adversaries, such as China, may well also help explain renewed interest within the PLA in the idea of a conventional ICBM, at least in part.

All of this also comes amid concerns that thresholds worldwide for the use of nuclear weapons may be lowering and new questions about the future of long-standing nuclear arms control arrangements. This includes criticisms about the deployment of U.S. Navy Ohio class ballistic missile submarines with Trident II missiles with lower-yield warheads and continued pressure from certain members of Congress to pursue the development of a new sea-launched nuclear-armed cruise missile.

In addition, the Russian government has suspended its participation in the New Strategic Arms Reductions Treaty (New START) with the U.S. government in response to its support for Ukraine. Just this week, Russian lawmakers approved the country’s de-ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, or CTBT, which could open the door to the resumption of live nuclear weapon testing.

The U.S. government has been advocating for all-new strategic arms control agreements that would include China, as well as Russia. So far, the Chinese government has rebuffed those proposals.

There is a broader concern within the U.S. military about the potential for a major conflict with China, especially over Taiwan, before the end of the decade.

The prospective risks that a Chinese conventional ICBM capability would introduce on top of everything else, “I think, highlights the importance of having clear and direct conversations between the U.S. and the PRC [People’s Republic of China] on these topics, which we’ll continue to pursue,” the senior U.S. defense official said yesterday during the briefing on the Pentagon’s new report.

All told, it remains to be seen whether the PLA will develop and field a conventionally-armed ICBM, or any other conventional missile system with intercontinental range. At the same time, this would be well in line with what has been seen from the Chinese military in the past, as well as other current strategic trends globally, despite the clear risks it presents.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com