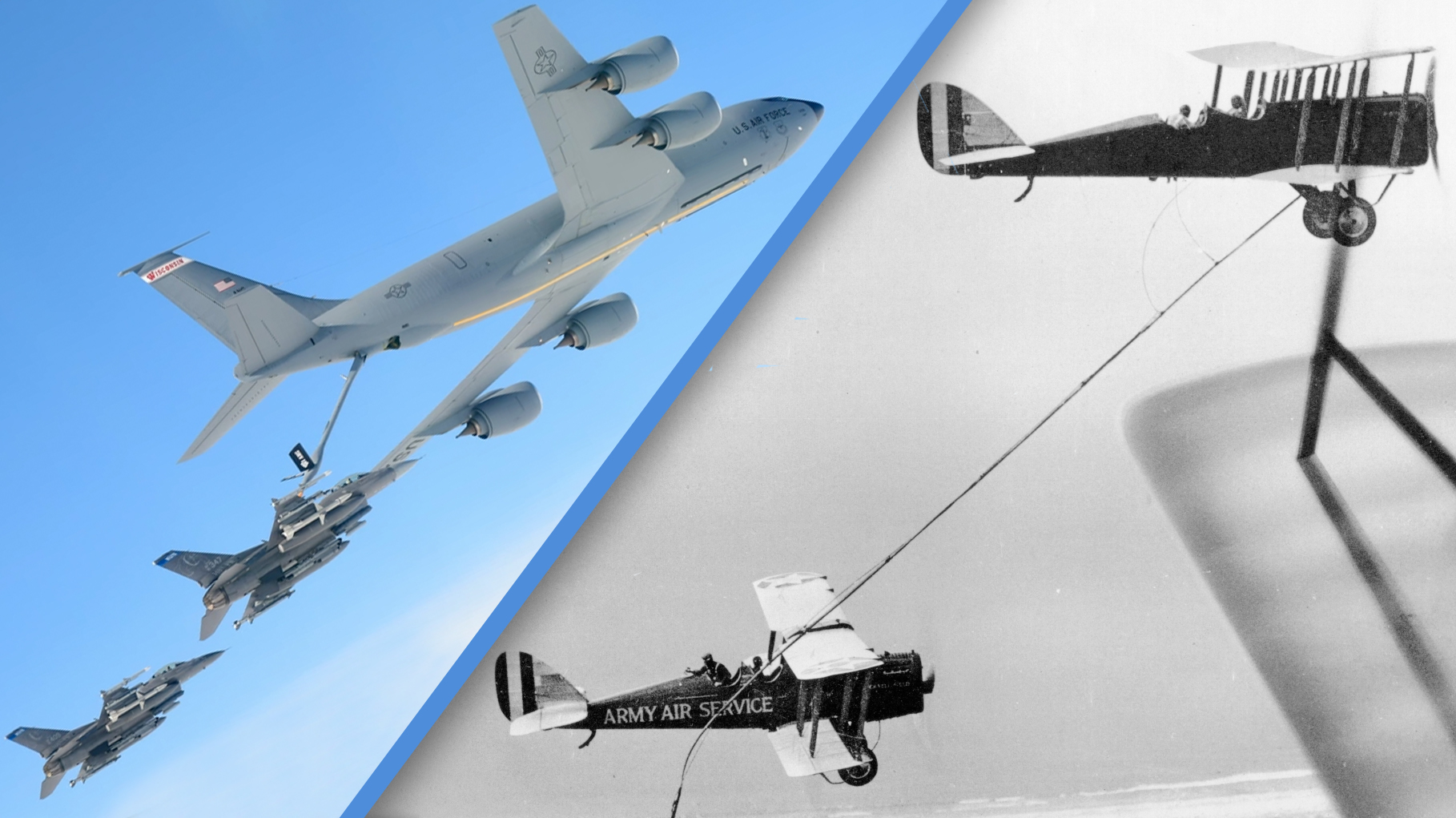

One hundred years ago today, over California, two U.S. Army Air Service crews passed a fuel hose between them, allowing one plane to be topped up by the other, and opening up what was nothing short of a revolution in military flying. That milestone — the first properly recorded, practical air-to-air refueling — is marked today by their successors, the tanker fleet of the U.S. Air Force, the most capable of its kind anywhere in the world.

To honor what the service describes as “100 years of aerial refueling excellence,” flyovers have been taking place today across all 50 states, with more than 80 tanker aircraft and 70 receivers. Participating tanker aircraft are the iconic KC-135 Stratotanker, the soon-to-be-retired KC-10 Extender, and the latest but still troublesome KC-46 Pegasus.

The 6th Air Refueling Wing at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, the oldest in Air Mobility Command, is leading the celebrations.

These aircraft perform a vital, if sometimes unsung role, ensuring rapid global reach for U.S. forces and their allies, not only extending the range of a wide variety of aircraft but also enhancing their lethality, flexibility, and versatility. At the same time, these tankers can also carry cargo and passengers, perform aeromedical evacuations, and they are increasingly taking on a number of other missions, too.

As the Air Force now begins to explore the potentially exotic tankers that will come after the KC-46, it’s worth going back to the events of June 27, 1923, to recall how far the art of aerial refueling has come in those 100 years.

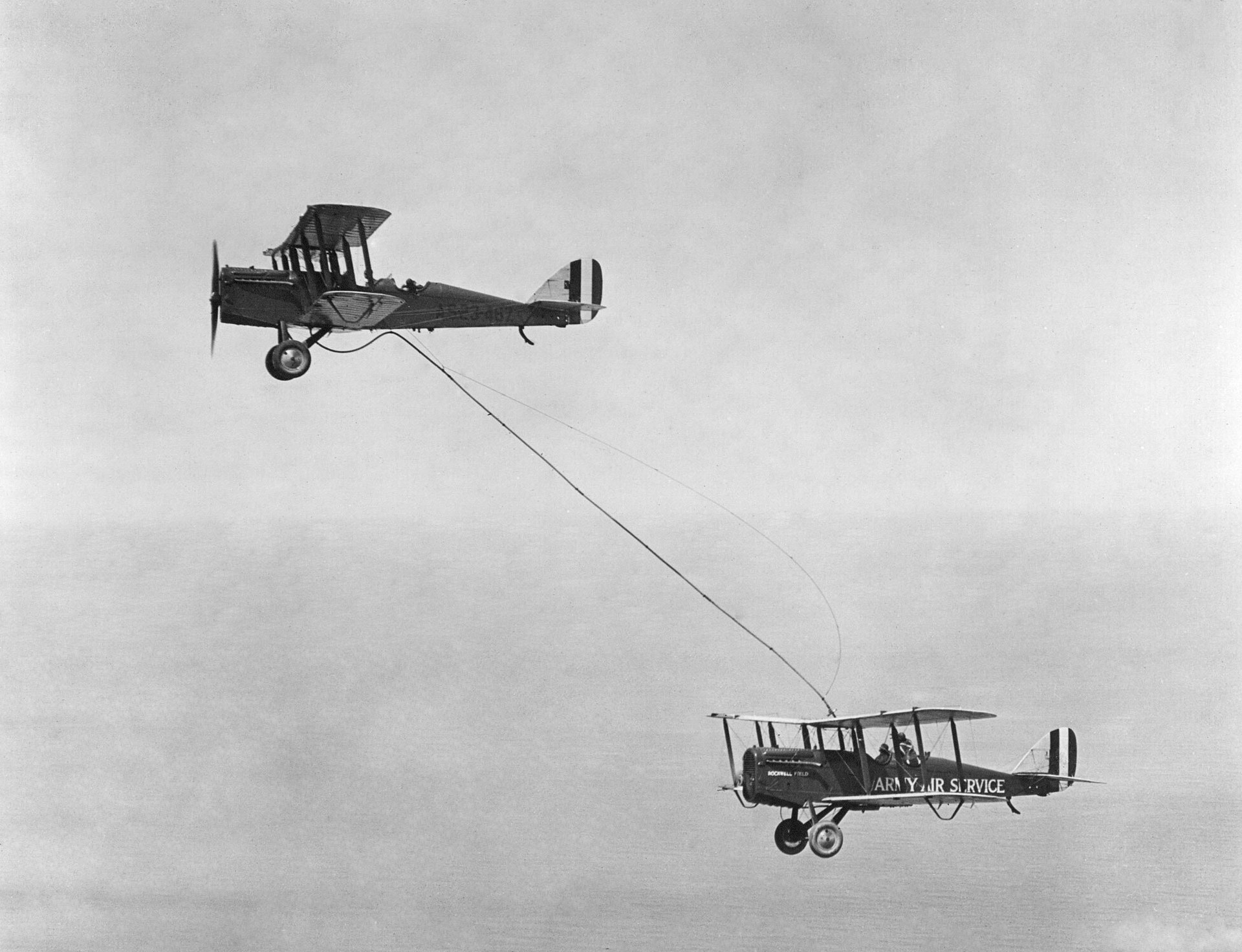

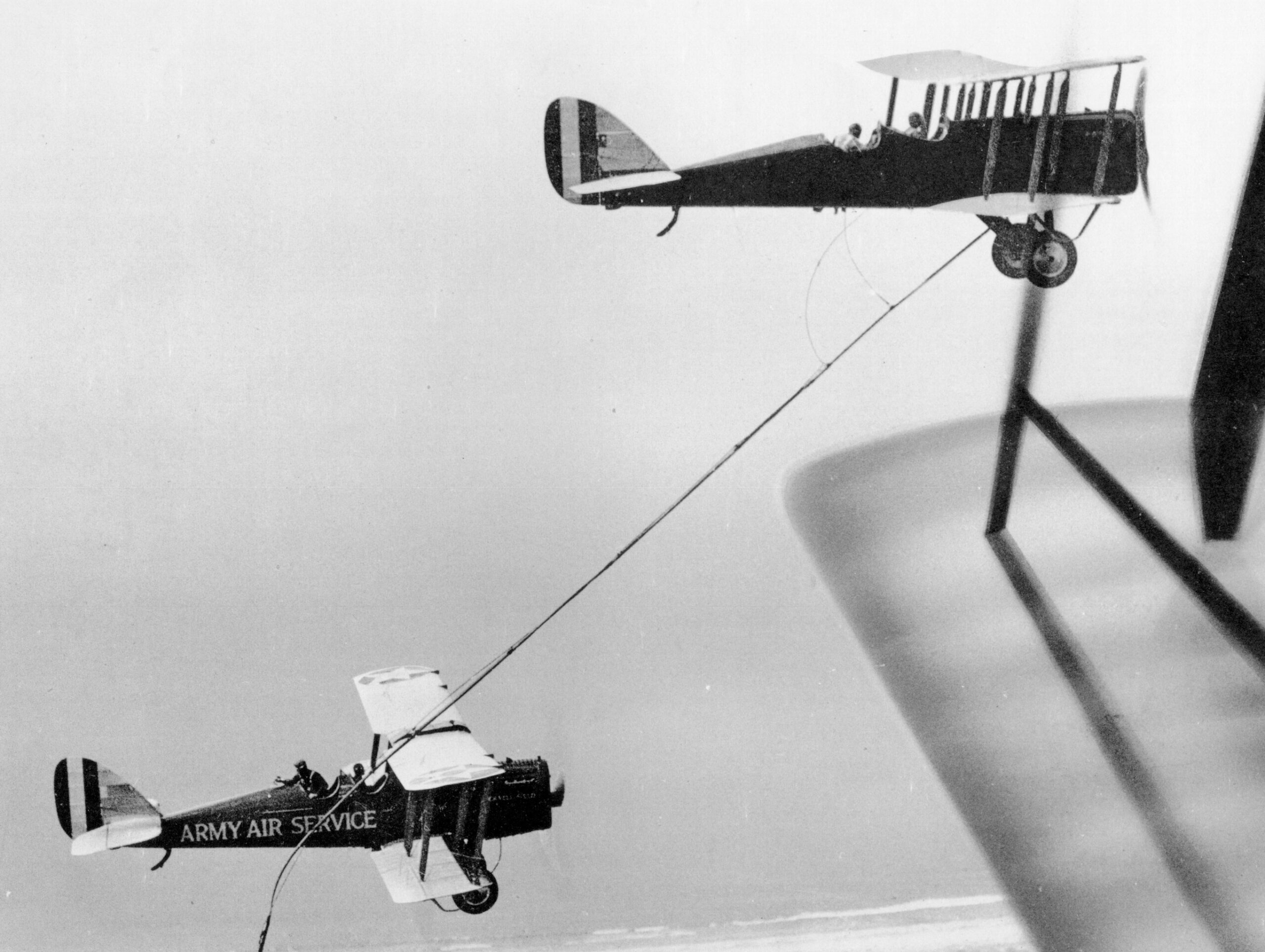

The aircraft involved were modified de Havilland DH-4B biplanes — a multipurpose British design that was widely used in a range of roles by the U.S. military. At the controls of the first aircraft were 1st Lt. Virgil Hine and 1st Lt. Frank W. Seifert, with the second machine crewed by Capt. Lowell H. Smith and 1st Lt. John P. Richter.

The two aircraft made ‘contact’ 500 feet above Rockwell Field, on San Diego’s North Island. Seifert, in the rear cockpit of the first aircraft, delivered a rubber hose to Richter, in the rear cockpit of aircraft number two. The tanker aircraft had both an extra 110-gallon fuel tank and a 50-foot metal-reinforced refueling tube that was lowered through a ventral trapdoor.

The process was later described in an official Air Force account as “you dangle it: I’ll grab it,” with the backseater in the receiver aircraft having to manually catch the tube, enter it into the filler, and then operate a valve to shut off the fuel when topped up. On this occasion, only 75 gallons of gasoline were actually passed down the tube to the receiver aircraft. Engine trouble for the receiver aircraft forced the mission to be cut short, with the receiver remaining in the air for 6 hours and 38 minutes. But the experiment had proven the range-extending promise offered by aerial refueling.

The same crews were involved in further trials with DH-4Bs followed in subsequent weeks, although, for added flexibility, the second mission added another tanker aircraft, crewed by Capt. Robert G. Erwin and 1st Lt. Oliver R. McNeel. On August 27 and 28, 1923, Smith and Richter’s aircraft remained aloft for 37 hours and 25 minutes, setting a new world endurance record in the process. This had been enabled through 14 midair refueling contacts with the two tankers. In total, the receiver aircraft had covered 3,293 miles, roughly the same distance as flying from Goose Bay, Labrador, to Leningrad in the Soviet Union.

This startling range prompted the next phase of the trials, on October 25, 1923, when Smith and Richter took off from Suma, Washington, close to the Canadian border, and flew south. Over Eugene, Oregon, their aircraft was refueled by Hine and Seifert, while more fuel was taken on above Sacramento, California, with Erwin and McNeel flying the tanker aircraft. After around 12 hours in the air, the Smith and Richter DH-4B was circling over Tijuana, Mexico, having proven the feasibility of a nonstop border-to-border flight. They then touched down in San Diego. The mission had demonstrated, too, how the 275-mile range of the basic DH-4B could be extended to 1,280 miles.

At this point, however, the U.S. Army Air Service was still a small and poorly funded organization and aerial refueling was hardly a pressing concern.

However, by 1928 the Army had returned to the idea, with an Atlantic-Fokker C-2 being prepared as the receiver that would take on fuel from two Douglas C-1 tankers, as part of an effort to set a new endurance record. The Fokker, named Question Mark, was crewed by aviators including Capt. Ira C. Eaker and Maj. Carl Spaatz, who would go on to take prominent positions in the U.S. Army Air Force’s strategic bombing arm in World War II. On January 1, 1929, the Question Mark took off on a flight that would eventually last 151 hours — more than six days in the air.

Thereafter, it was in the United Kingdom that many of the major technological developments in air-to-air refueling took place, pioneered by Sir Alan Cobham and his Flight Refuelling company. These included a practical probe-and-drogue refueling system, with the tanker trailing a hose with a stabilizing drogue on the end, and the receiver aircraft being fitted with a rigid probe that was plumbed into the fuel system. The drogue served as a conical guide for the probe, with valves automatically opening and closing.

After World War II, the U.S. Army Air Force’s interest in aerial refueling was reawakened, to extend the range of its bombers that were now taking on an increasingly global mission. Flight Refuelling’s looped-house system was adopted at first. This involved the receiver aircraft trailing a steel cable which was then grappled by a line shot from the tanker. The line was then drawn back into the tanker then connected to the refueling hose. The receiver could then haul back in the cable and hose. Once the hose was connected, the tanker would climb above the receiver aircraft to allow fuel to flow under gravity.

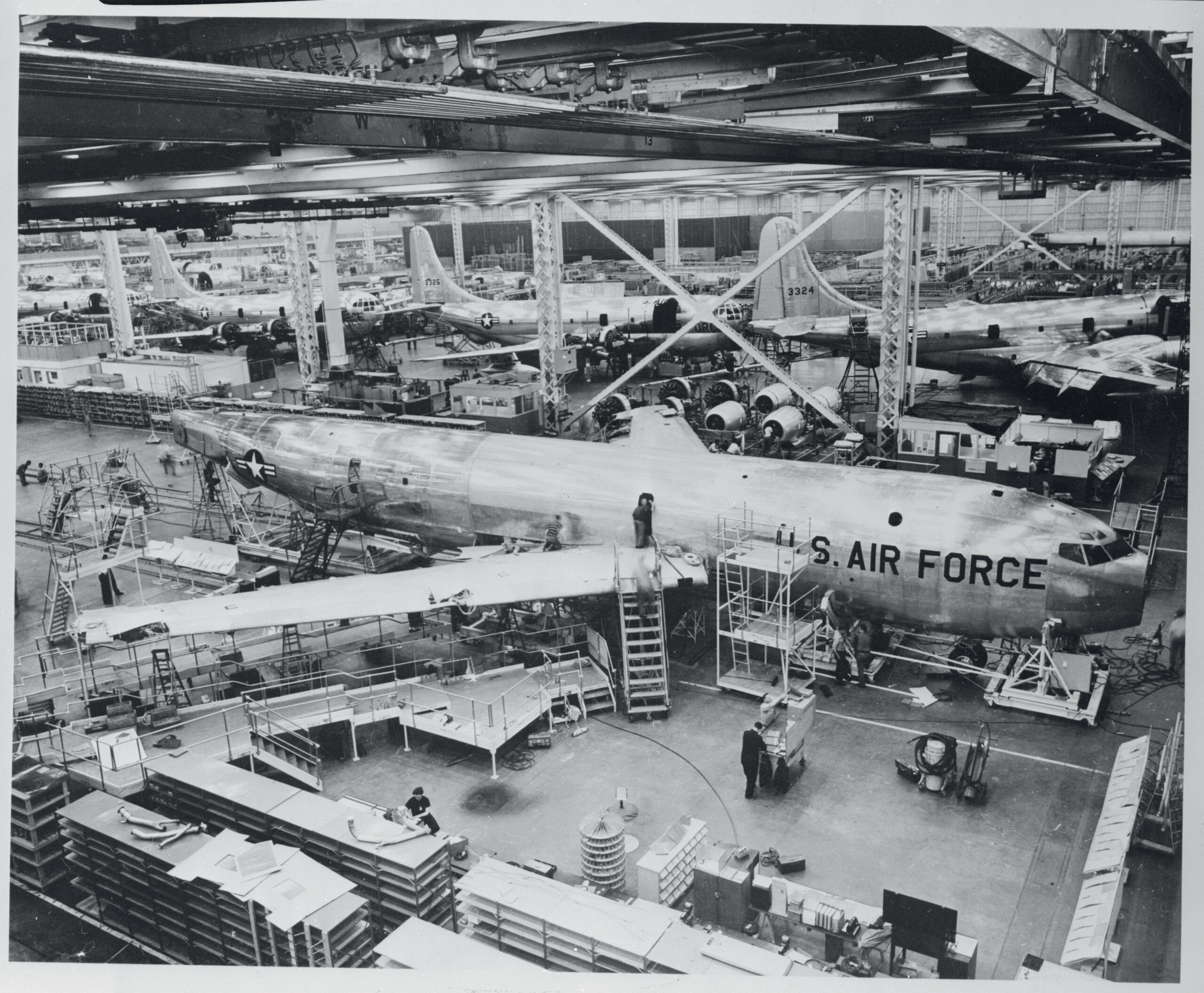

Using Flight Refuelling kits, 92 B-29 Superfortress bombers were converted into KB-29M tankers, and another 74 B-29s got the appropriate modifications to operate as receivers. A first hook-up took place on March 28, 1948, by which time the operator was the independent U.S. Air Force.

Even before this date, Boeing was looking at improvements to aerial refueling technology and in December 1947 received funding to develop what became the flying boom system. This was intended to deliver fuel at a much faster rate and instead of the flexible hose that had been used in refueling systems from the DH-4B all the way up to the KB-29, it used a telescopic tube, connected to the receiver via a pivoted coupling. Aerodynamic surfaces at the end of the boom allowed it to be ‘flown’ into a receptacle on the receiver aircraft by the boom operator.

A pair of B-29s were modified as YKB-29Js to test the flying boom before 116 more Superfortress bombers were converted into KB-29P tankers.

Expensive, bulky, and heavy, the flying boom nonetheless offered the considerable advantage of delivering fuel more quickly and it remains the Air Force’s primary aerial refueling method, although Flight Refueling’s probe-and-drogue system also began to be used by the service in the early 1950s. This more compact system may have delivered fuel at a slower rate, but it allowed three aircraft to be refueled at once. This method was first tested by a YKB-29T tanker, with a hose drum unit in the rear fuselage and refueling pods under the wings. In production form, the three-point tanker was the KB-50J, which saw notable service in the Vietnam War.

For a while, Tactical Air Command fighters were fitted with probes to allow rapid deployment, and the same system is widely used today, including by the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, as well as Air Force helicopters. Today, U.S. Air Force KC-135 tankers feature a boom-drogue adapter kit — known as the “Iron Maiden” or “Wrecking Ball” due to its metal frame having the ability to do serious damage to a receiving aircraft — or they carry refueling pods under the wings to service a wider range of receivers. The KC-10 and the KC-46 have built-in hose and drogue systems.

While the KC-97 was a vital and prolific stopgap tanker for the Air Force, remarkably, the tanker that really revolutionized the aerial refueling game was the KC-135, which remains in widespread service today. The KC-135 brought aerial refueling into the jet age, offering the speed needed to keep station with fighters as well as a new type of boom that pumped out up to 1,000 gallons of fuel a minute. The first example was delivered to the Air Force in January 1957 and the KC-135 is still the mainstay of the service’s aerial refueling fleet. Championed by Gen. Curtis LeMay, the KC-135 would soon transform Strategic Air Command’s ability to send bombers against targets deep in the Soviet Union.

“Air refueling propels our nation’s air power across the skies, unleashing its full potential,” said Gen. Mike Minihan, Air Mobility Command commander, in a press release prepared for today’s centennial events. “It connects our strategic vision with operational reality, ensuring we can reach any corner of the globe with unwavering speed and precision. Air refueling embodies our resolve to defend freedom and project power, leaving an indelible mark on aviation history.”

“As we embark on the next 100 years of air refueling, we will continue to strengthen our air mobility excellence,” Minihan continued. “We must leverage the remarkable capabilities of air refueling to preserve peace, protect freedom, and bring hope to the world. As Mobility Airmen, we write the next chapter of air refueling.”

As to what the next 100 years of aerial refueling tankers might look like, there remain many questions about what comes after the KC-46, the acquisition of which is ongoing. The Pegasus is a traditional non-stealthy commercial-derivative design and continues to suffer from significant issues with key systems, as you can read more about here.

Meanwhile, the Air Force is stepping up the pace of the Next-Generation Air Refueling System (NGAS) program, announced earlier this year, which you can read more about here.

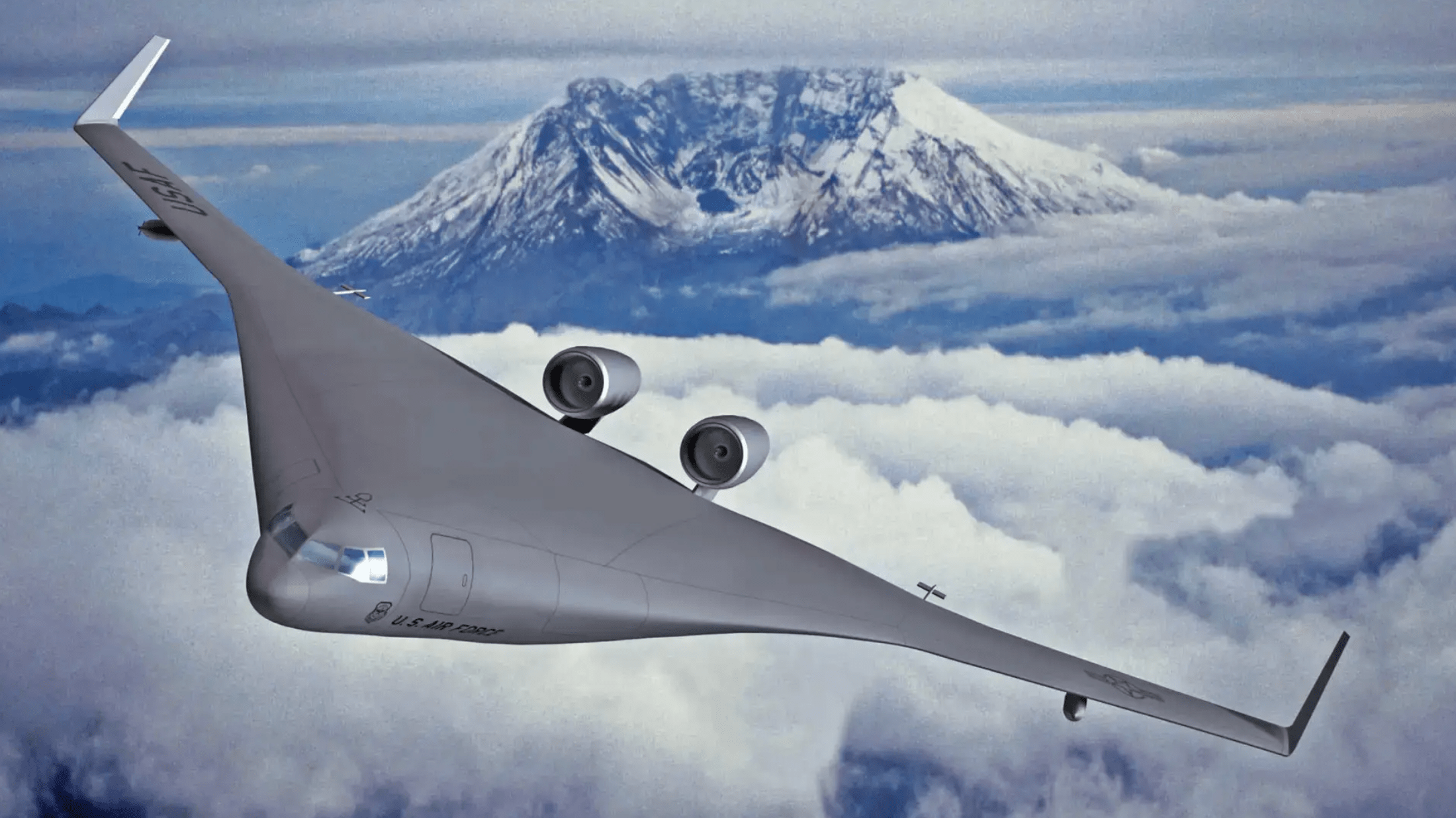

While the KC-46 employs broadly similar design solutions to the KC-10 and even the KC-135 that came before it, there are clear indications that NGAS will see much more radical ideas being explored.

Above all, NGAS is supposed to be able to provide support in “contested scenarios,” something that tankers have traditionally avoided. Lockheed Martin and Boeing have already been exploring design concepts with blended wing-body planforms that would offer some degree of stealth to enhance their survivability. The need for a stealth tanker is something that The War Zone has been discussing for many years now.

“The Department of the Air Force (DAF) is pursuing continued development of the next generation of tanker concepts that address the changing strategic environment,” the Air Force lays out, in a Request For Information (RFI) released in February. “The team is seeking information on innovative industry solutions that might fulfill the most stressing and complex air refueling mission requirements of the future fight.”

That same RFI doesn’t explicitly reference “stealth” or “low-observability” characteristics, although the mention of “contested scenarios” is a clear indication that the Air Force wants its future tankers to be able to support operations in higher-threat environments. Such environments would include the Asia Pacific region, where a potential conflict with China would see tankers playing a more important role than ever.

As a more immediate measure, the Air Force is meanwhile making current tankers more survivable and giving them new missions via podded systems and possibly “loyal wingman” type drones.

Another eye-catching aspect of NGAS is the Air Force’s desire to now have the next-generation tankers in service by the mid-to-late 2030s. That could still provide time to develop a stealthy tanker, and perhaps even more exotic tanker concepts — including pilot-optional or entirely uncrewed aircraft — could still be realized.

There are other options out there, too, such as the Air Force proposal for a podded aerial refueling boom that could be integrated as required onto various platforms to turn them into tankers.

In the meantime, the service is still looking at the option of an interim tanker buy, variously known as KC-Y or the “bridge tanker,” which could bring more KC-46s or Lockheed Martin’s proposed new derivative of the Airbus A330 Multi-Role Tanker Transport (MRTT) dubbed the LMXT.

An added impetus for some kind of interim tanker comes from the fact that the Air Force’s current acquisition plans for the KC-46 do not provide enough new tankers to replace older KC-135s and KC-10s on a one-for-one basis. NGAS, whatever new technologies it might bring, might just involve too long a wait for the Air Force, although there is also opposition to a bridge tanker, leaving that program effectively in limbo.

Whatever the future Air Force tanker fleet looks like, it’s clear that these aircraft will continue to play an absolutely essential part in operations by this service and its allies. With a need for more survivable tankers, there are also growing signs that the Air Force’s next aerial refueling tanker could incorporate elements just as visionary as those that were trialed by that pair of biplanes over California, a full century ago.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com