When Ukrainian forces began to take apart several pieces of captured or partially destroyed Russian military equipment, they found a strong reliance on foreign microchips – especially those made in the United States – according to component lists Ukraine intelligence shared with The War Zone.

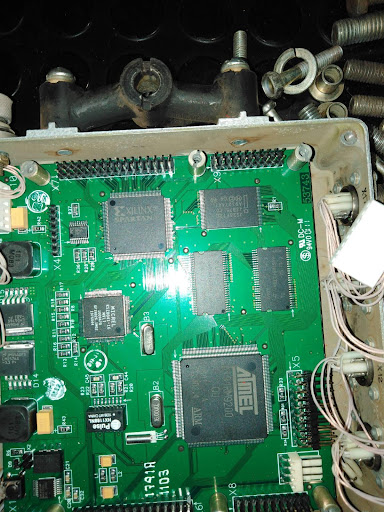

The chips in question were found inside a recovered example of the 9S932-1, a radar-equipped air defense command post vehicle that is part of the larger Barnaul-T system, a Pantsir air defense system, a Ka-52 “Alligator” attack helicopter, and a Kh-101 (AS-23A Kodiak) cruise missile.

The component list offers some of the most detailed information to date about the extent of where the Russians are getting critical microchips, semiconductors and other components. The items on those lists raise serious questions about Russia’s ability to produce the technological components its war machine relies on and the ability of countries like the U.S. to keep those technologies secure, an expert tells The War Zone.

In the Barnaul-T air defense command post vehicle, for example, Ukraine intelligence said its specialists found eight microchips from U.S. manufacturers like Intel, Micrel, Micron Technology and Atmel Corp. in its communications systems.

Ukrainian specialists also found five U.S.-made chips – manufactured by AMD, Rochester Electronics, Texas Instruments, and Linear Technology – in the direction finder of a Pantsir air defense system.

There were at least 35 U.S.-made chips found in the Kh-101 cruise missile, including those manufactured by Texas Instruments, Atmel Corp. Rochester Electronics, Cypress Semiconductor, Maxim Integrated, XILINX, Infineon Technologies, Intel, Onsemi, and Micron Technology.

When they opened up the turreted electro-optical system of the Ka-52 Alligator, Ukraine specialists found 22 U.S.-made chips and one Korean-made chip. The U.S. manufacturers included Texas Instruments, IDT, Altera USA, Burr-Brown, Analog Devices Inc., Micron Technology, Linear Technology and TE Connectivity.

While the U.S. and several other nations instituted sanctions after Russia launched its full-on invasion on Feb. 24 that prevented selling them equipment including microchips, there is no indication that any of the chips in these captured or destroyed Russian assets violated any of those provisions. In fact, some of the manufacturers were previously subsumed by other companies.

IDT, for example, was purchased by the Japanese firm Renesas in 2019. Micrel was purchased by Microchip Technology Incorporated in 2015. Atmel Corp. was also purchased by Microchip Technology, in 2016. Cypress Semiconductor Corp. was acquired by Infineon Technologies in 2020. Altera was purchased by Intel in 2015. Burr-Brown was purchased by Texas Instruments in 2000.

The origin of the microchips found in these Russian weapons is unclear. These chips would not necessarily have to have been sourced directly from the manufacturers. Also, there is a massive and largely unregulated market for recycled chips, largely emanating from China, and many of them appear to be quite old.

Ukraine intelligence officials who provided the component list also could not say where the chips originated.

But Skip Parish, a counter-drone/directed energy weapons/electronic warfare/red team subject matter expert for NATO and the U.S. military, reviewed the list of components provided by Ukraine intelligence and said they raise a number of issues.

It highlights, he said, a “total dependence on western technology” in applications of “integrated chips sets in key sensitive working parts of Russian weapon systems – targeting, navigation, communications and execution of the weapon.”

It also shows the “breakdown or non-existent U.S. controls” in International Traffic in Arms Regulations, “both supporting investigations when found in foreign weapons.”

On May 11, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo told a Senate hearing that sanctions against Russia were forcing it to seek alternate sources of key components.

“We have reports from Ukrainians that when they find Russian military equipment on the ground, it’s filled with semiconductors that they took out of dishwashers and refrigerators,” Raimondo testified, who recently met with Ukraine’s prime minister.

While components found in appliances, for instance, are harder to prevent falling into the wrong hands, U.S. officials, Parish said, do have the authority to prevent shipments of those dual-use chips if they consider the application to have critical military uses.

And, he said, this highlights and offers the need for “a clear path to stopping Russian weapons success without being there, and “a crash domestic program to stop the shipments of technology” from U.S. allies Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, collectively known as the “Five Eyes.”

While Raimondo testified that Ukraine said Russians have been using appliance parts in its tanks, that is not likely the case in the more sensitive systems laid out by Ukraine intelligence, Parish said.

“The optics in the Ka-52 armed helo targeting and the missile guidance systems,” he said, “are of the greatest concern.”

The War Zone reached out to all the microchip manufacturers named in this story and several responded. Most said they no longer do business with Russia. Many said they either don’t know or can’t control where their chips wind up. And one company disputed the Ukraine intelligence assertion that its chips were found in Russian military equipment.

A spokeswoman from Onsemi, for instance, pointed out that her company’s chips are not military-grade, thus easily obtainable.

Stefanie Cuene, head of public relations for onsemi, said that her company’s chip “is a commodity, not military grade and available anywhere on the open market.”

“We already viewed the war in Ukraine with serious concern,” Gregor Rodehüser, spokesman for Infineon Technologies told The War Zone. “Your message deepens these concerns.”

“While we cannot comment on the topic specifically, Infineon has implemented appropriate measures to ensure compliance with the sanctions.”

After the beginning of the war in Ukraine, he said, “we have stopped all direct and indirect shipments to Russia, Belarus and the respective Russian-backed regions in Ukraine. This also includes technical support.”

Infineon Technologies, Rodehüser said, has not yet “found any evidence of military use of our products in Russia. We therefore screen customers and markets sourcing our products for compliance with legal export regulations.”

Intel said while they can’t know where their chips wind up, they no longer do business with either Russia or Belarus.

“While we do not always know nor can we control what products our customers create or the applications end-users may develop, Intel does not support or tolerate our products being used to violate human rights,” said Penny Bruce, Intel’s director of corporate communications. “Where we become aware of a concern that Intel products are being used by a business partner in connection with abuses of human rights, we will restrict or cease business with the third party until and unless we have high confidence that Intel’s products are not being used to violate human rights.”

Intel, said Bruce, “has suspended all shipments to customers in both Russia and Belarus.” Additionally, “Intel will continue to comply with all applicable export regulations and sanctions in the countries in which it operates; this includes compliance with the sanctions and export controls against Russia and Belarus issued by the US and allied nations.”

Analog Devices “is committed to full compliance with U.S, EU and other countries’ laws including export controls, trade sanctions and regulations,” said Ferda Millan, a company spokeswoman.

TE Connectivity, meanwhile, disputed the Ukraine intelligence component list.

“We did a search in our parts database and were not able to find a match to the part number you provided,” said Jeff Cronin, a company spokesman.

The issue of foreign components winding up in Russian military equipment despite sanctions has come up before.

After Russia first invaded Ukraine in 2014, it was hit with a previous round of sanctions.

Those, however, apparently did not prove foolproof.

It is unclear how concerned the Commerce Department might be over the microchips Ukraine intelligence said were found on the Russian air defense systems, helicopter, and cruise missiles.

The department did not respond to a request for comment by Friday afternoon. We will let you know what they say if they do respond.

There is already a lot of evidence that existing sanctions are hurting Russia’s defense industry. And Ukraine claims that the older components Russia is using, particularly in the Kh-101, make them less effective. But given Russia’s reliance on the large numbers of microchips, semiconductors, and other components floating around – and its close relations with China, a top manufacturer and recycler of these parts – the long-term effects of sanctions, at least in regards to high-tech components like chips, remains to be seen.

So too does the U.S. reaction to the chips they are using

Contact the author: howard@thewarzone.com