Nearly half a decade ago, The War Zone broke the story on what was then called the F-15X. The fact that the Air Force was willing to make an about-face on its ‘all or nothing’ 5th generation tactical fighter strategy and buy its first F-15 Eagles in two decades was stunning and, at least to many, remarkably logical. For a military branch plagued with years of puzzling and arguably totally unrealistic force structure and procurement choices, it seemed that rationality had returned — with the help of some backroom political wrangling. Regardless, with growing threats abroad, the ever-shrinking and aging USAF fighter fleet demanded relief. What is now known as the F-15EX Eagle II was meant to help give it some.

Fast forward to the present day, and what was a highly promising, low-risk procurement initiative, once presented as a cornerstone of the Air Force’s future tactical aviation plans, now appears to be at a fork in the road. Instead of choosing a clear path on either side, the Air Force appears to be flailing through the thick brush in between without a real sense of direction.

The core of the issue is the slashing of the F-15EX procurement plan from a minimum of 144 airframes to just 80. In nearly a year since this change emerged as part of the USAF’s 2023 budget request process, there have been no clear answers as to why buying just 80 F-15EXs makes any sense or what that number aims to accomplish. Now, with another budget request on the horizon, it is hoped that the F-15EX’s fate will be better articulated, if not sealed, one way or another.

What exactly is going on here is not clear. The F-15EX program has become something of a canvas for people to paint their own force structure hopes and fears on — a procurement Rorschach test, if you will.

At this time, there doesn’t seem to be really any firm plan behind the reduced F-15EX buy, or at least there isn’t a plan the powers that be are willing to share at this time. But introducing a new advanced tactical aircraft sub-type into the inventory with just 80 airframes to show for it is anything but promising. In fact, it goes against the Air Force’s own stated problem of having too much diversity in its tactical aircraft inventory.

Then there is the stark reality that small or shrinking fleets of aircraft become increasingly costly to sustain and crew without economies of scale, setting them up for being slashed further, or entirely, in future budgets. The A-10 is currently the poster child for this. It’s like the reverse of the classic Pentagon procurement death spiral. Meanwhile, these shrinking fleets are justified as ‘assuming some risk’ by Air Force brass, in which cost savings are realized by drawing-down fleet sizes. This is basically an attempt to steal from the present force structure to pay for a more advanced one that will hopefully materialize sometime in the future.

Considering the realities around the globe today, ‘assuming some risk’ is certainly the right way to put it.

If the Air Force truly intends to buy just 80 F-15EXs, as they have stated at the highest level, I would argue that they should not buy any and should cut their losses immediately. This is a very hard pill to swallow, but based on what we know now, and saving a few caveats we will discuss below, an 80-aircraft fleet makes no sense and sets the F-15EX cadre up for being slashed totally in the future.

Instead, the Air Force should proceed with its original 144 F-15EX buy, or a well-justified number very near or greater than that amount.

Here’s why.

Eagles For Eagles

The F-15EX was meant to provide an off-the-shelf replacement for the rapidly aging F-15C/D fleet that remains a backbone of America’s counter-air strategy, especially when it comes to protecting the homeland.

The F-15C/D fleet is far beyond its best years. Major structural components, including the aircraft’s wings, are in need of replacement and invasive rehabilitation of the aircraft has been put off. Many of the ‘air superiority Eagle’s’ subsystems are old and hard to support. Some suppliers that once provided these components are long gone. Restrictions on performance due to airframe age issues limit the aircraft’s capabilities. They are taking longer to repair and keep flying and are costing more to fly. Technological relevance is also becoming a more glaring issue without further costly upgrades.

The situation is long overdue for a remedy.

The idea once was to deeply upgrade 179 of the cream of the F-15C/D fleet into the ‘Golden Eagle’ configuration that would serve for decades more. As even the newest airframes began approaching 40 years old, and so much work was needed to upgrade them, replacing them outright seemed like a more logical option. There just happened to be an aircraft to do that and its development was largely paid for by the Saudis and the Qataris.

It turns out, the best aircraft to replace an F-15 just so happens to still be an F-15.

Enter the F-15EX.

New F-15EXs would not only last much longer in terms of the hours they could fly, but they would be far more relevant to a future fight than what a service life extension program on the USAF’s tired Eagles could provide. But now, years after the F-15EX program was spun-up, its slashed procurement number doesn’t deliver on an F-15C/D replacement. In fact, nothing about the current procurement number adds up at all.

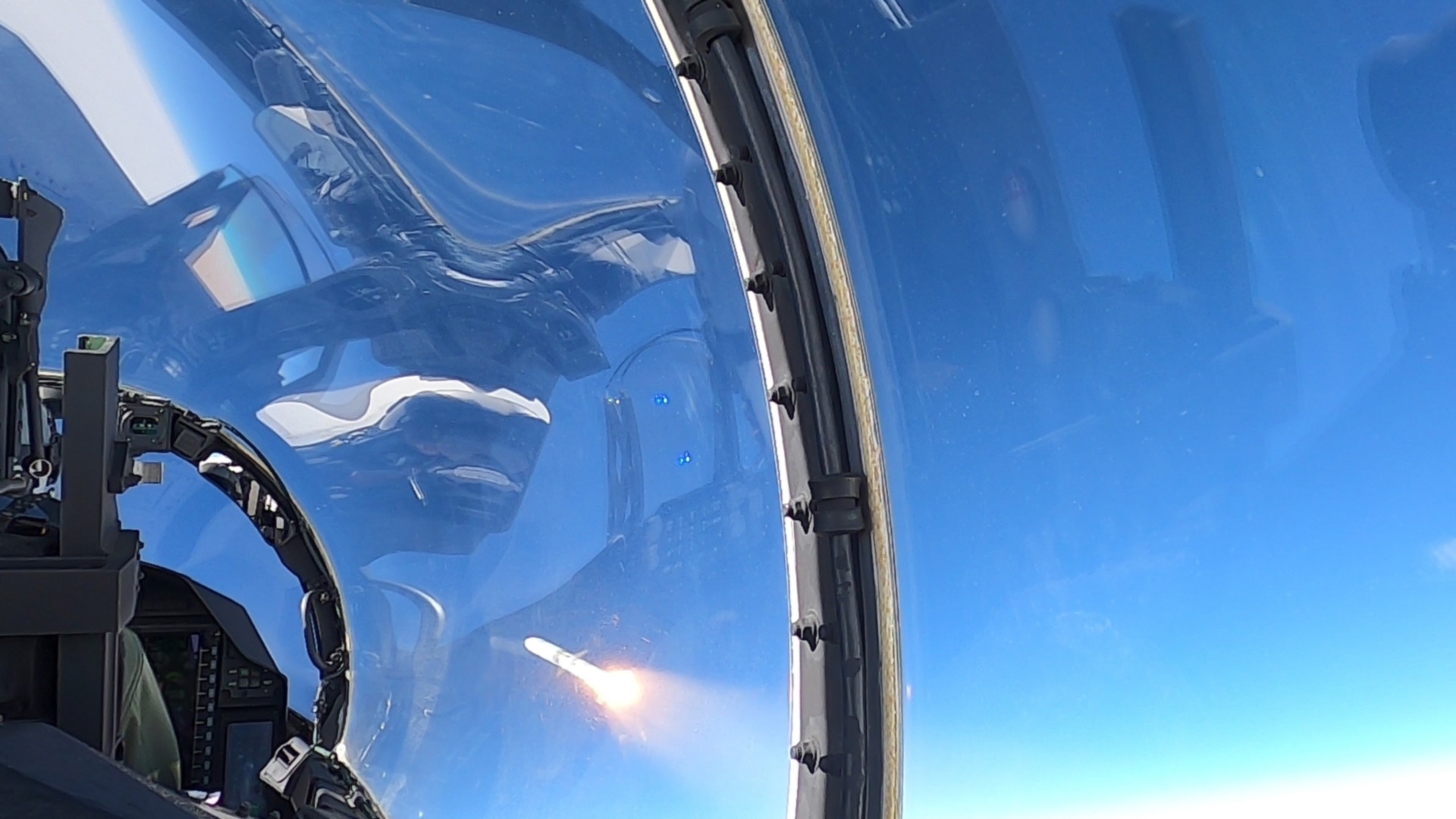

Author’s note: You can read all about the capabilities and what it is like to fly the ‘Advanced Eagle’ on which the F-15EX is based here, and our extensive reporting on the F-15X/EX’s capabilities here and here.

Breaking Down The Numbers And Nonsense

80 F-15EXs gives you roughly three combat squadrons of 21 airframes (18 primary airframes and three back-up airframes), a small schoolhouse squadron, and a couple of aircraft for testing, evaluation, and tactics development. And this is really squeezing that 80 aircraft number. 18 aircraft squadrons would make it far more feasible. This could be justified by the F-15EX being far more reliable than the old, technologically inferior jets they will replace, but still, it would be three fewer airframes than what is generally allotted F-15C units today.

As the F-15C/Ds are in dire need of replacement, the Air Force has been shrinking down the already dwindling air superiority Eagle fleet by shuttering two squadrons at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa and one at RAF Lakenheath in the United Kingdom. It is also winding down F-15C/D operations at the service’s prestigious Weapons School. Meanwhile, the Florida Air National Guard’s (ANG) 125th Fighter Wing, one of five F-15C/D-equipped ANG units that defend the seaward approaches to the continental United States, has been selected to receive F-35As in a puzzling move and will begin receiving the stealth jets next year. So the F-15C/D force that numbered well over 200 airframes as of around a year ago is already in rapid decline.

When it comes to the current state of the F-15EX program, just two of the jets have been delivered to the Air Force to date and those aircraft are doing test and evaluation work out of Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. According to the Air Force’s responses to our queries in January, six more F-15EXs are supposed to be delivered this year and 24 in all have been officially ordered.

The units that are slated to actually receive the F-15EX — there are only two at this time — are both part of the Oregon Air National Guard. This includes the 173rd Fighter Wing, the current and only F-15C/D schoolhouse at Kingsley Field in Klamath Falls, and the 142nd Fighter Wing in Portland. These are stellar units and considering the schoolhouse and Portland Air National Guard Base’s relatively close proximity and same command, having these units receive the EX first is glaringly logical. Still, as it sits now, these two units are an island onto themselves when it comes to future F-15EX operators. At the time of writing, even the California ANG, a major F-15C/D operator, has received no official word on what will replace their Eagles, for instance.

It was originally assumed that the F-15EX would, at the very least, replace the continental United States-based ANG F-15C/Ds. The 144 number made some sense in that regard. All five F-15 ANG units — two located on each coast and one along the Gulf of Mexico — tasked with protecting the approaches to the United States would have their fleets recapitalized. This would have equipped ANG F-15C/D units in California, Oregon, Massachusetts, Florida, and Louisiana with new F-15s, in addition to the schoolhouse at Kingsley Field and some test jets. This plan would put the F-15EXs where they would matter most and would have created a core community for the type with a clear mission set. It would have also stabilized these units for many decades to come.

That clearly is no longer the plan.

It was also hoped by some that the 144-jet buy would lead to wider procurement and the two F-15C/D squadrons at Kadena Air Base could be reequipped with F-15EXs. This would also make sense considering their forward locale and a huge threat picture to contend with that already requires very long-range missions.

It turns out, at least for now, those Eagles are being replaced with nothing. Instead, fighter units — especially F-22s from Alaska — will send a handful of jets to Okinawa on a rotational basis to sit alert and provide some presence. In fact, this is already happening as the Eagles rapidly depart their long-held roost on the island. The Air Force says a future permanent replacement is still being debated.

The truth is, the bench is looking very thin even in peacetime as far as assets available to provide a forward presence in Okinawa, and any other locale for that matter. F-22 Raptors, which are in high demand around the globe and are extremely finicky in terms of readiness, are being called on to fill the gaps left by the F-15s, with precious hours being eaten up on long transits to and from Alaska. And even the notoriously tiny F-22 fleet of just roughly 180 jets, of which only about 125 are actually combat capable, seems expansive compared to what’s now planned for the F-15EX. And the Air Force wants to drastically cut down its F-22 fleet too, another ‘assumption of risk’ to pay for future programs.

Kadena aside, with just 80 aircraft now planned, who would get the other two combat-capable squadrons of F-15EXs beyond the one in Oregon? The California ANG, Massachusetts ANG, and Louisiana ANG, all F-15C/D operators, are the clear options. But still, that leaves one of these units without new Eagles II to replace their aging F-15C/Ds. And once again, Florida, which provides critical air defenses to a highly strategic area, is giving up their F-15C/Ds for F-35s, not F-15EXs.

So basically, the Air National Guard will be standing up an entire schoolhouse and the logistics and unique needs of a new sub-type, which includes tactics development and future upgrade and sustainment work, just to equip three combat-capable squadrons.

With critical information missing about the justification for the 80 aircraft buy and the F-15EX program as a whole, one could argue that it seems firmly in a procurement purgatory of sorts. It is like a placeholder of a program that is drawing finances with capability trickling in, but could easily be vaporized by the interests at play and the powers that be, leaving some major problems in its absence, including a small fleet of hugely capable, but orphaned airframes.

So what are the variables at play that could be driving this situation and what are the options as to how to fix it?

The Best Option: Just Buy 144 F-15EXs

This is the simplest solution. Stick to the minimum 144 aircraft buy. Stabilize the fleet plan and get the absolute most out of what will be a very versatile and totally proven aircraft that is ready to fight today and will fly for many decades.

Remember, the F-15EX has a 20,000-hour airframe life. The F-35A has an 8,000-hour airframe life. This is one way the F-15EX gets done dirty when people make comparisons between it and the F-35, often based on unit cost alone, which is about equal. We are talking about two-and-a-half times the airframe hours out of the box with the F-15EX. That is not a knock against the F-35A at all. The F-15EX is just a very mature aircraft that has been optimized for longevity over a much younger one. Also, the F-15EX’s cost per flight hour — $29,000 — is based on 50 years of F-15 performance metrics across many air arms and on directly comparable aircraft that have already been flying with an allied air arm for years. The maturity of the aircraft will also allow it to maintain superior readiness and fly more often. There is less risk of degradation in readiness during prolonged high-tempo combat operations, too, compared to its 5th-generation counterparts.

In the homeland defense role, which is the bread and butter of the F-15C/D ANG units, the F-15EX’s payload, range, open architecture, very advanced electronic surveillance and warfare suite, and overall adaptability will be of incredible use over many decades of service. You do not need a stealth fighter to do this mission. In fact, much of what is traded in terms of reliability, performance, and sustainment cost for low-observability hinders the homeland defense mission. This includes raw kinematic performance. The F-15 can get places very fast when it needs to and still have fuel left over to do something once it is there, which is critical for quick reaction alert missions.

The F-15 also has a huge aperture for a massive radar in its nose. This is important for maximum reach and fidelity for the homeland defense air sovereignty, especially when it comes to cruise missile defense and spotting and engaging other low-observable, as well as low-flying targets with small radar cross-sections, like drones.

The ability to easily and cheaply bolt on capabilities and upgrade the aircraft via changes to its outer moldline is also a huge bonus.

Beyond that, the F-15EX can efficiently carry 12 AIM-120s today, but that number can be nearly doubled in the future. Smaller air-to-air weapons could balloon the F-15EX’s air-to-air magazine depth, too. Once again, this could prove critical to defending against volume threats like cruise missiles and drones. Even laser-guided rockets are being tested to help in this regard.

Larger missiles are also a major factor here. The F-15EX’s AN/APG-83 radar would benefit from weapons that can make use of its immense range. The same can be said for advanced networking capabilities that the F-15EX will be able to leverage for long-range targeting.

Using the F-15EX as an arsenal ship of sorts, especially when equipped with long-range missiles, in cooperation with its stealthy counterparts operating silently and forward, is a tactic, among others, we have long discussed. The F-35 and F-22 have weapons bays that are basically built around the AIM-120 AMRAAM’s dimensions. Strapping larger air-to-air missiles on them would negate their stealth advantage and severely impact their performance. There is no such limitation on external carriage with the F-15EX and its ability to lift very heavy loads could allow it to provide very long-range missile shots.

This is especially true as the Air Force works to develop fighter-launched missile-carrying drones that will provide a huge boost in survivability and tactical flexibility in air-to-air engagements. But systems like these, such as LongShot, will be heavy and would negate a stealthy fighter’s low-observable advantage. The F-15EX, on the other hand, is incredibly well suited to deploy these air-launched drones, and doing so would allow it to compete more aptly in contested airspace. Pairing F-15EXs with these capabilities alongside their 5th gen stablemates opens up the tactical possibilities even more.

Unrelated to the air-to-air combat arena and as we first detailed in our initial report on the F-15X, the type is an ideal hypersonic missile delivery platform, too, which would be a critical role in a high-end conflict. This has since been openly touted by the USAF as one major benefit of the F-15EX program.

Hypersonic standoff weapons delivery, and really any long-range standoff weapon delivery that can be accommodated by the F-15, such as AGM-158 JASSM cruise missiles, could be a great secondary mission for air defense-focused ANG F-15EX units without having to embrace a full air-to-ground mission set. But with just 80 aircraft in the entire fleet, and homeland defenses to cover, only a limited amount of aircraft would even be available for it and even traditional counter-air missions in a crisis.

The ability to carry a second crewman is never a bad thing either, especially in an increasingly complex battlespace. This is where the F-15EX, with its fully missionized dual cockpits equipped with wide flat panel displays, can shine — as an airborne battle manager.

But more on that in a moment.

Taking all these factors into account, I would argue that F-15EXs should replace all five continental U.S.-based F-15C/D units, including Florida, and go a step further.

Having F-22s sit quick reaction alert (QRA) in Alaska and Hawaii is a baffling waste of resources. And it’s not just about stuffing a couple of aircraft into an alert barn and waiting for the klaxon to go off.

The QRA mission is very resource-intensive. At least three aircraft and a spare are usually at the ready to fulfill an alert mission. This is true 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Out of a squadron of 18 F-22s, of which roughly half are mission capable at any given time, that is a massive resource sink. Also, this is not just some basic skill set. This mission must be trained for and ground crews must be set aside to fulfill it.

The F-22 is an amazing fighter and capable in this role, but the F-15EX is far more capable and efficient in doing so on virtually every level. When an F-22 is needed for a specific homeland defense task, like chasing a high-altitude balloon, for instance, they can be tasked from other units to do so. In fact, that was the case when the Chinese Spy Balloon first appeared over Montana. That is a very niche mission set that an F-15EX could still do, regardless.

F-22s are absolutely not known for their range, either. They wear 600-gallon fuel tanks for the QRA and air sovereignty mission. This largely removes their stealth and super-cruise advantage and they are far more dependent on alert tankers than an F-15EX would be. Also, in this standard QRA configuration, they would not be able to achieve the altitudes and speed needed to surveil and engage things like the Chinese Spy Balloon in the way we saw it done, regardless.

The F-15EXs will not be delivered with range-extending conformal fuel tanks, at least for the first batches, but if taxed with very long-range air patrol and intercept missions over remote areas, they could and should be outfitted with them. This was done with F-15C/Ds in Alaska and Iceland for many years, for instance. You can read our full report on the state of the F-15EX’s conformal fuel tanks here. Regardless, an F-15EX with conformal and two drop tanks offers remarkable endurance.

The F-22 also carries fewer weapons and lacks critical electro-optical long-range identification capability, too. The Raptor may be getting an infrared search and track (IRST) system in the years ahead, which is becoming very important for the homeland defense role, but the F-15EX has the capability now and it has no stealth and little performance to trade for it.

Above all else, the F-22s are precious machines. While the limited information we know about the USAF’s Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) initiative seems promising, we have no real idea when that capability will actually be ready in quantity and hurdles are bound to occur in realizing it. In addition, we know the USAF is planning on acquiring around 200 examples of the type, which will cost hundreds of millions each, at this time. Will they even make it to that number? History would say the chances aren’t good. As such, the F-22 force should be preserved, especially considering the ops tempo they will likely face with growing global threats in the years to come.

With all this in mind, I propose that the F-22 force be consolidated and focused 100% on its top-end mission, not chasing down wayward Cessnas or escorting Tu-95s over the Bering Sea.

The F-15EX, on the other hand, would absolutely shine in this role and fulfill it for well over half a century, if need be.

So, how would consolidation of the F-22 force work? I would suggest arming Hawaii ANG with F-15EX and realigning its F-22s to Langley AFB in Virginia and Elmendorf AFB in Alaska. That would result in two master F-22 bases, both of which have organic aggressor support.

In exchange, Hawaii, Oregon, and California, who are already masters at the homeland air defense mission, could cover Alaska’s alert commitment. In fact, Californian F-15s have already been training for this. Even nearby aggressor F-16s at Eilson Air Force Base have covered alert duties for the heavily taxed Raptor units based in Anchorage recently. All three of these contributing F-15EX units could be up-sized with a few airframes and some personnel to offset this rotational mission requirement.

If Florida ANG sticks with its F-35 transition, which is likely the case at this point, this force structure should be fully obtainable, including a handful of aircraft left over for test and development. This is well within the scope of the original 144 aircraft buy, including adding a few extra airframes to units in California, Hawaii, and Oregon to help offset the Alaskan alert commitment.

Then there is Kadena Air Base in Japan. I would argue the F-15EX is uniquely suited to reequip the wing there, even if it just reequips a single squadron instead of two. The Eagle II’s long-range counter-air capabilities, large air-to-air missile load, and potential as a hypersonic weapon launch platform would fit well for this mission. Japan also has an expansive F-15 sustainment ecosystem. Upgrades to facilities there would also be minimal to accommodate the F-15EX.

This addition would result, roughly, in a 160 aircraft buy. The number sits around 180 with a second Kadena squadron that would directly replace all of the F-15C/Ds that are leaving. Alternatively, if squadrons were capped at 18 aircraft, and jets from the schoolhouse and active squadrons were also loaned for test and Weapons School duties, this entire force structure, with one squadron at Kadena, could be had for the original procurement number of 144 aircraft.

Once again, the best thing about the F-15EX is it is a long-term homeland defense and general counter-air operations solution, but it is also an omni-role aircraft that can do any other fighter task, and more, if needed. This includes the full spectrum of air-to-ground operations, if called upon, although this would require a major shift in training and mission focus for the units that are slated to receive the F-15EX.

The hypersonic missile delivery mission, or a number of standoff weapons delivery profiles, would not be such a tall order. But specialists could also be trained for any role and take advantage of the F-15EX’s second seat and fully missionized rear cockpit. This could put less stress on pilot training.

That rear cockpit could also prove very relevant to the introduction of manned-unmanned teaming, especially before extreme degrees of trust and AI infusion exists on collaborative unmanned platforms. The F-15EX will be uniquely suited for this manned-unmanned teaming concept as it emerges. New capabilities that emerge in the coming decades could be rapidly adapted for pairing with the Eagle II, especially with the help of its big airframe and open-architecture systems.

The big takeaway is that although the F-15EX’s mission is fairly narrow at this time, it really has to be viewed as a platform in a very broad sense of the word. It can rapidly adapt to the times and the needs of the Air Force to do what it is asked of it perhaps more so than any other fast jet tactical platform around.

Above all else, completing the original 144 jet buy will make standing up and F-15EX enterprise truly worth it and will act as a guard against it being slashed into oblivion in the future. It will create a critical mass that can very efficiently solve many force structure problems for decades to come while also providing great adaptability for whatever comes next in terms of air combat capabilities. It would also allow the limited F-22 fleet to focus on what it was designed to do — lead the high-end fight.

In summary:

- Buy 144 F-15EXs minimum.

- In addition to both Oregon units, equip California ANG, Louisiana ANG, and Massachusetts ANG with F-15EX (ideally Florida too, but that seems unlikely at this point).

- Realign Hawaii ANG’s F-22s to Alaska and Virginia creating two master F-22 bases with organic aggressor support that can focus entirely on their top-end mission.

- Equip Hawaii ANG with F-15EX.

- Have Oregon, Hawaii, and California ANGs cover Alaska alert commitments on a rotational basis with each squadron getting three additional airframes and extra personnel to help offset that requirement.

- Recommend adding additional airframes beyond the 144 F-15EX buy to equip Kadena Air Base in Okinawa with at least one F-15EX squadron, possibly two.

Option 2: Cancel The F-15EX Now

While having to figure out what to do with the 24 F-15EXs already on the books could be an issue, that is a lot better than having 80 of them with a dubious future and no economies of scale to benefit from. To be frank, I would recommend replacing F-15C/Ds with F-35As instead.

This may sound like blasphemy to some, and it’s unfortunate to pit the two types against each other as they are actually incredibly complementary. Still, doing so would provide a more certain future for current F-15C/D units than operating a tiny fleet of a specific sub-type. The F-35A can execute the homeland air defense mission, although with many of the tradeoffs we have discussed already, and upcoming Block IV aircraft should (we are still working on a confirmation) be able to carry six AIM-120s internally. With the addition of two AIM-9Xs on the wings, this would give the F-35A the current Eagle’s max air-to-air loadout capabilities without dirtying up its wings too much with external stores. Smaller hit-to-kill air-to-air weapons could expand this magazine depth in the not-so-distant future. Regardless, for normal air sovereignty missions today, an F-35 with four AIM-120s and two AIM-9s is more than adequate, but the threat picture is changing, as we discussed earlier.

Block IV aircraft will also feature a new, more powerful radar and many other improvements, although those aircraft will not be available until later in the decade.

Currently serving blocks of F-35As have internal Electro-Optical Targeting Systems (EOTS) that are roughly equivalent to a first-generation Sniper Advanced Targeting Pod in terms of long-range aerial visual identification capabilities and the jets have a secondary infrared search and track pseudo function. This is not the same as a dedicated IRST like the F-15 is already getting, but it’s possible that a sensor could be hung externally if its IRST function is not satisfactory for the air defense role. The F-35’s Distributed Aperture System, which provides 360-degree electro-optical situational awareness, could be somewhat beneficial in the homeland defense role for some missions, as well. Block IV F-35s will also have a EOTS that will be far more capable than the one it has now, along with a huge slew of other improvements that will make it a substantially more capable aircraft than F-35s being delivered today.

Waiting for F-35s will mean F-15C/Ds still in service may have to soldier on even a bit longer than with the F-15EX replacement option. But once again, this is just a few squadrons at this point. Also, the schoolhouse requirements could be integrated into the sprawling F-35 training architecture and thus a separate schoolhouse could be eliminated entirely.

Cost-wise, the unit price is comparable between F-15EX and F-35A. Operationally, the F-35s are more expensive, at least for now, and have a lot of additional on-site infrastructure requirements. And again, their airframe life is much less than F-15EX out of the box. Being able to haul very heavy outsized loads is also not a possibility. Nor is the ability to fly dual-crew missions and upgrading the jet quickly by bolting on new features isn’t without tradeoffs.

In the homeland defense role, the F-35 has drawbacks compared to the F-15EX, especially in terms of speed and range when fully tanked-up. New enhanced engine upgrades and external fuel tanks could offset the latter issue to some degree and the F-35A does have remarkably good range for a single-engine fighter as it is. The twin engines of the F-15EX could be viewed as an advantage for very long-range remote patrols, too.

But if the Air Force can hold out, getting Block IV F-35s to replace its F-15C/Ds would be a more attractive option and better value proposition, than getting current block models. It will be a very capable aircraft, although one that is substantially less suited to the role the F-15EX is intended to provide.

Buying new-build F-16s is another option, but even in their latest form, they are not nearly as capable as an F-15EX for the primary role intended. Many of the same issues with the F-35 also comport to the F-16, including not being able to accommodate some of the unique missions, such as outsized payload carriage, that the F-15EX can offer beyond its air defense and organic ground attack capabilities. Range and speed are also markedly inferior.

Still, they can absolutely do the mission, they do so every day, but F-35 would be a more likely option on every level and the USAF has shown no interest in introducing new F-16s into the fleet.

The F-35 buys stability for what seems to be a remarkably unstable situation. Any qualms about extra fleets within fleets and economies of scale are eliminated by going the F-35A route. And as we discussed earlier, in the case of Florida ANG, this has actually already happened. The looming Block IV upgrade aircraft just sweetens the proposition.

Option 3: Give F-15EX To The F-15E Strike Eagle Community

At this point, it does not make sense to buy 80 F-15EXs under such a nebulous set of circumstances just two equip a few ANG squadrons. Other options seem to exist. One would be to target the F-15EX program at replacing at least a portion of the heavily tasked fleet of F-15E Strike Eagles, a possibility we have explored before. In turn, some of the F-15Es, which are already getting major upgrades, could be handed over to the Air National Guard to replace its F-15C/Ds.

This would allow the F-15E community, which can make the most out of the F-15EX’s multi-role capabilities, to gain fresh and more capable airframes while still leaving the door open to replace the entire fleet. Even if the 80 aircraft buy were to go through, it would allow for the majority of earlier F100-PW-220 powered jets, which feature significantly less thrust than their F100-PW-229 equipped stablemates, to get transferred to the Guard units. To our understanding, the first 127 F-15Es featured the less powerful motors, the majority of which are still in service. Around 219 F-15Es are in the active inventory.

If the F-15EX buy was expanded, it could replace all of the F-15E aircraft. Meanwhile, the Guard would be able to leverage the best of the F-15E fleet for decades to come, many of which are already being upgraded with the same radars and electronic warfare systems as what’s found on the F-15EX.

While an interesting proposition to ponder, at just 80 airframes, this would again leave a relatively small fleet within a fleet. Replacing the majority of the F-15E fleet would be a different story.

Option 4: Centralizing The Homeland Defense Mission

There has long been talk of reconfiguring how the Air Force executes the homeland air defense mission. The base realignment and closure battles of decades past have sometimes centered around these ideas, including one particularly intense round under Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld.

The idea has been floated in various forms that you consolidate the NORAD air defense mission, or at least parts of it, further than it already is among a smaller number of units and then deploy fighters from those units to alert sites rotationally year-round to fill the QRA need left open from shuttered, permanently-based units. This is similar to the aforementioned idea of sending F-15EXs from other units to Alaska to cover the gap that would be left by refocusing the F-22’s duties there, but on a much grander scale. It would also likely be paired with a massive shift in tactical fighter basing and force structure, and could change the role and national presence of the Air National Guard’s tactical fighter force in significant ways.

Regardless, one could see how 80 F-15EXs could be used in such a way, with some units getting no aircraft at all and thus not being able to fulfill their local QRA mission, or being shuttered altogether.

While this sounds like an intriguing idea in some respects, doing so is more complicated and risky than it seems. The local knowledge and familiarity units tasked with regional QRA mission build-up over the years make for a more effective end product. Having a full local squadron ready to switch to full-out homeland defense with a full wing trained and ready to flex to that mission in a crisis is also something that cannot be replicated by centralizing the mission and distributing small sets of fighters to remote QRA locations.

The large swath of airspace alert fighters currently cover is also telling. For instance, Oregon’s 142nd Fighter Wing has to cover areas from Northern California into Canada, and deep into the interior of the country over Idaho and Montana, for instance. At most locales, the alerts consist of a couple of aircraft with a spare or two, so this is a lot of airspace to cover by just two QRA jets, especially in a sudden crisis. Spreading this coverage even thinner and deploying it in a less effective manner would definitely be ‘assuming additional risk.’

As noted earlier, locally based squadrons can also quickly spin up a much larger air sovereignty force posture quickly if need be, as they did after the attacks on 9/11. This would be much harder to achieve and sustain with a scaled-back, distributed QRA arrangement.

Finally, you would end up tasking certain Guard units so heavily with air sovereignty missions that they would be very challenged to do anything else. Right now, Guard fighter units are basically deployed in a similar way to active units. The Air Force’s tactical jet force has shrunk so much — it’s a shadow of itself from even when Operation Iraqi Freedom was launched — that there is little slack in the system. In other words, this could greatly degrade the USAF’s overall deployable fighter end-strength at any given time and have other negative downstream effects, as well.

There is also the idea of creating a major unit that just handles the homeland air defense mission. That would be their only mission and they would be specially equipped and trained for it. It’s an interesting concept as doing so would free up the rest of the force solely for higher-end operations. But this unit would be unlike any currently in the Air Force and would have to be very large in size in order to cover the NORAD commitment now fulfilled by many units scattered around the country. This would be true even just for the F-15 and F-22 units that cover the homeland defense mission. Many airframe hours would be spent just transiting to alert sites during rotations around the United States and manning those sites would be a huge logistical operation.

I don’t see how any of these solutions are better than what exists today. In fact, they seem highly detrimental to end strength and flexibility, as well as the country’s domestic static air defense posture.

The Wild Card

There seems to be something missing here and that could be just the Air Force not being sure it knows exactly what it wants. Navigating the special interests and political rocks and shoals of a fighter procurement deal is also a potentially perilous task, especially when cutting back a buy or eliminating it altogether. On the other hand, there are indicators that the truncated F-15EX purchase could be indicative of a bigger sea change in the Air Force — the arrival of unmanned combat air vehicles, finally.

While the USAF is keeping its cards close to its chest in this regard, the Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) program is becoming a major component of the USAF’s future architecture. We also know that Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall and Air Force’s top uniformed officer, General Charles Q. Brown, said that some of the F-15 units may end up with drones or no flying mission at all. You can read our full report on their eyebrow-raising comments here.

These were purposefully vague statements and ones that are probably troubling to some, to say the least. But it may fit into a larger F-15EX play. As could the recent news that the USAF is planning on buying at least 1,000 advanced collaborative air combat drones as part of its CCA initiative.

The F-15EX, with its two crew cockpit, large flat panel displays, high-end mission and display processors, room for communications expansion, ease of overall upgradability, long endurance, and very advanced electronic warfare suite, among other attributes, make them uniquely suited to usher in the manned-unmanned teaming air combat revolution. This movement is now seen by top Air Force brass as a major opportunity for countering China.

What I am getting at here is there may be a push to augment the F-15EX force with unmanned collaborative teaming aircraft. One could imagine that smaller F-15EX squadrons, say 14 instead of 21 jets, could be augmented by a couple dozen collaborative unmanned aircraft. Basically, this would achieve a larger combat mass without the same manned tactical fighter footprint. Still, there is no indication that squadron inventory formats — for those that actually get the F-15EX — will be altered.

Unmanned aircraft dominating the high-end of the air combat universe will undoubtedly be the reality sooner than most may think. So, could the F-15EX be used to springboard this change? Absolutely. But for the primary mission they are being procured for, there are major issues with such a plan.

For instance, just operating unmanned aircraft in and out of the places ANG F-15s operate from daily — often dual-use civilian/military airports — would be extremely challenging, at least at this time. The same can be said for going to and from the training airspace these aircraft use. But as part of a major overhaul of how the USAF’s tactical squadrons are organized, located, and implemented in a time of war? It’s possible.

A more likely plan would have some F-15C/D units get fully outfitted with their full complement of F-15EX aircraft, but other F-15C/D units could be converted over to provide unmanned capabilities to pair with the F-15EX for non-homeland defense roles. Hence some squadrons having fighters and others drones, but where they work and train together for certain mission sets. This training would be done at specific locations where the aircraft can operate together more freely as they would in wartime. These drone squadrons could also provide similar collaborative capabilities to other manned types, as well.

It all sounds intriguing, but actually making it work, while also providing for the homeland air sovereignty mission and having enough fighters to deploy for traditional taskings abroad — at least until the unmanned capability set is fully proven — is a very tall order. But maybe the reduced F-15EX buy, at least for now, leaves some flexibility to employ such a strategy in the future.

This is all speculative and the discussion here should be treated just as possibilities at this time. Clearly, based on the USAF’s leadership’s comments alone and current stated planning, something doesn’t add up, and a concept like this would explain a lot. It would also be hugely controversial and could face stiff opposition in Congress.

On the other hand, if the F-15EX’s collaborative drone is mature and has been developed and proven, at least to a large degree, clandestinely, this could help justify such a seemingly risky force structure change.

What To Do With Orphaned F-15EXs?

If the F-15EX was cut entirely and just a couple dozen airframes made it into the USAF’s hands, or were still under contract when such a decision came to pass, there are options as to what to do with them.

First off, another round of reports recently stated that Israel is actively pursuing the acquisition of a couple of dozen F-15EXs. While we have heard similar reports before without subsequent confirmation, such an impending request could give the USAF an easy exit from the F-15EX program entirely. Considering the aid that is offered to Israel, the USAF’s orphaned Eagle IIs could be ‘paid for’ with those funds. The U.S. would get the benefit from a more capable IAF — a key airpower partner in the region — and funds could be freed up to acquire whatever will take the place of the F-15EX program. It’s really hard to imagine a more seamless scenario in which Israel gets what it wants and the Air Force moves on from the F-15EX it doesn’t seem to really want, at least at this time.

The F-15EXs could also be sold off to other existing F-15 customers. As explained earlier, the configuration is based directly on the Qatari F-15QA, which was derived from the Saudi F-15SA that came before it. If U.S.-specific gear is removed and the jets are reconfigured to Qatari or Saudi specifications, they could take them off the USAF’s hands — for the right price.

Even without a foreign buyer, the F-15EXs that are being delivered or under construction could still play a valuable role for exactly what we discussed above — working to develop the manned-unmanned collaborative air combat architecture of tomorrow. Sure, that would be an unfortunate use for such a capable aircraft, but it would be extremely important work. Testing other capabilities, including new weapons, tactics, communications, and sensors, which the F-15EX is already doing to a certain degree, could also prove useful. In addition, these jets could also be used, even if just partially, in an aggressor role, which would undoubtedly be very welcome.

Maybe it’s possible that aircraft not under construction could be released from contract for a penalty, too.

Of course, even having to write about this possibility is very unfortunate. Axing the program would be a huge missed opportunity, but just buying 80 airframes is arguably a worse outcome.

With any luck, the USAF will return to its original procurement plan, or clarify its 80 aircraft buy in such a way that it actually makes any sense and doesn’t gut critical capabilities to pay for other notional ones far out on the horizon. And hopefully, we will get this clarification in the upcoming Fiscal Year 2024 budget request.

But in the meantime, it feels like the F-15EX went from a promising ray of logic in an often illogical USAF procurement maelstrom to a puzzling glint.

Contact the author: tyler@thedrive.com