The latest U.K. drone program seeks to field a high-performance uncrewed aerial system (UAS) that will be able to fly autonomously alongside crewed aircraft, as well as operate in swarms. The new drone, named Jackdaw, after a member of the Corvid family of birds, is expected to take on a wide variety of missions and to do all this at a low enough cost that commanders will consider it “disposable” — meaning they are willing to sacrifice it in contested environments.

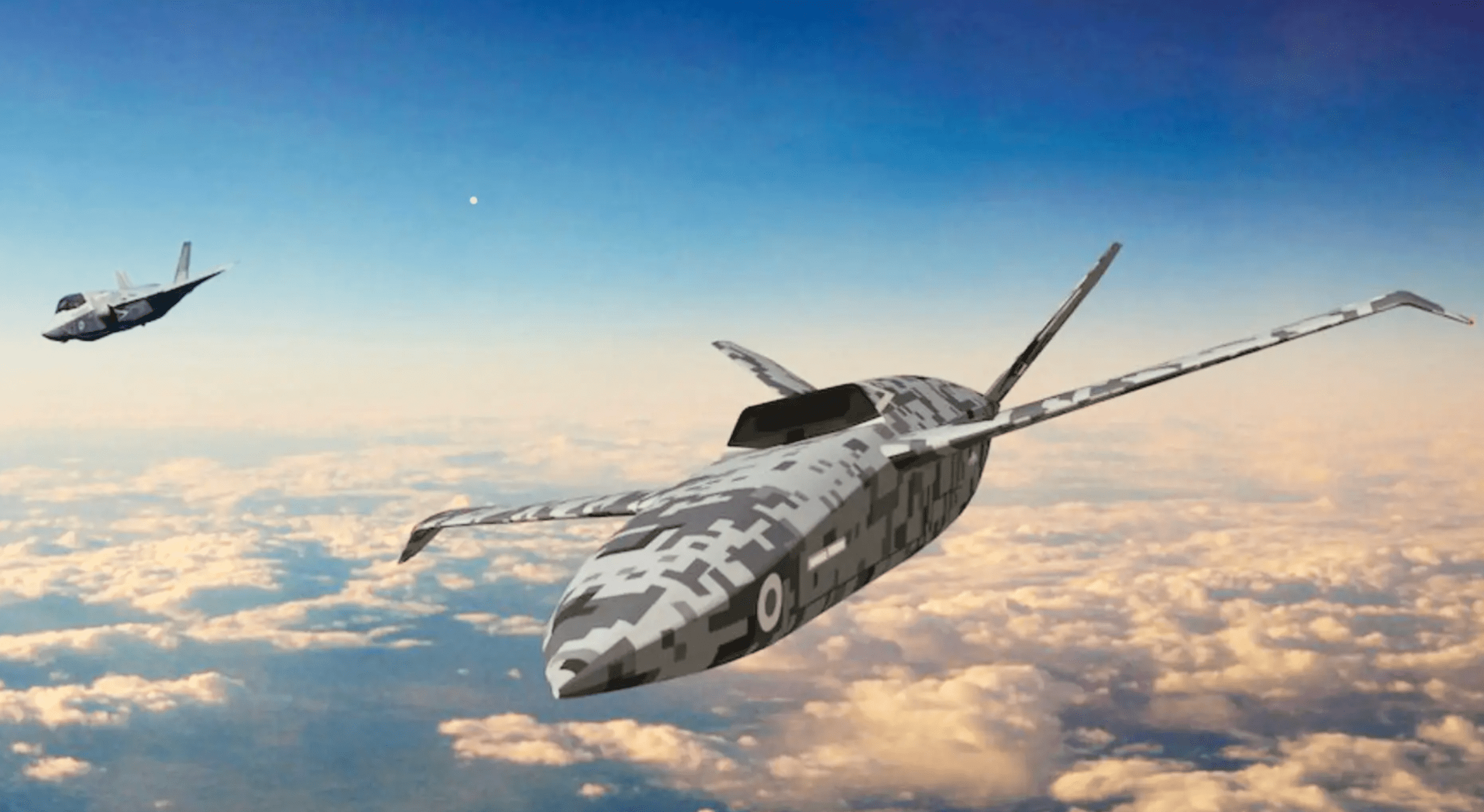

The Jackdaw program was announced today by QinetiQ, the U.K. defense technology company that emerged from the government’s secretive Defense Evaluation and Research Agency (DERA). QinetiQ unveiled a model of the drone and provided details and artist’s concepts at the Defense & Security Equipment International (DSEI) tradeshow in London.

What’s immediately interesting about the Jackdaw is that leverages some of the same kind of low-cost thinking that has led to the concept of “attritable” drones in the United States, in particular. Attritable is normally taken to refer to a drone that’s inexpensive enough that it can be used on high-risk missions that it is likely to not return from, while also being capable enough to be relevant for those missions. More recently, however, the U.S. Air Force in particular has stepped back from this term and begun to describe lower-cost drones in terms of “affordable mass,” a concept we have covered in the past. QinetiQ also stresses that the Jackdaw is designed to be reusable, too.

QinetiQ, too, describes the Jackdaw, in its current form, as providing “significant and affordable combat mass and battlespace capabilities,” which would seem to directly reflect current U.S. Air Force thinking.

As for being “disposable,” here it seems that QinetiQ is aiming to build upon the kind of low-cost drone designs that it already produces for use as aerial targets, like the Banshee series, which you can read more about here. In broad terms, the Jackdaw concept also looks similar to the jet-powered Banshee Jet 80 series, with its cropped-delta wing and single tailfin. However, rather than engines in the fuselage, the Jackdaw features a pair of jet engines mounted externally on the rear of the fuselage.

Like the Banshee, the Jackdaw will also be used for training, both as an airborne decoy and for threat representation — mimicking other potentially hostile platforms including “swarming threats and sophisticated threat payloads.”

More critically, however, QinetiQ sees the Jackdaw also flying a range of combat missions, as follows:

- ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) — reconnaissance and intelligence gathering to support commanders’ situational awareness

- Electronic warfare — utilization of the electromagnetic spectrum to counter adversaries

- Active and passive decoy — representing higher value or crewed systems in order to protect lives and vital assets

These will be achieved using a modular design concept, although the planned payload of 66 pounds is notably small and would preclude the carriage of most weapons, for example.

The concept is most similar to the handful of low-end loyal wingmen-like drones that U.S. defense contractor Kratos has adapted from its own portfolio of target drones. These include UTAP-22 and Air Wolf. These are seen as highly attritable and simpler than their more advanced CCA-like counterparts that continue to emerge today.

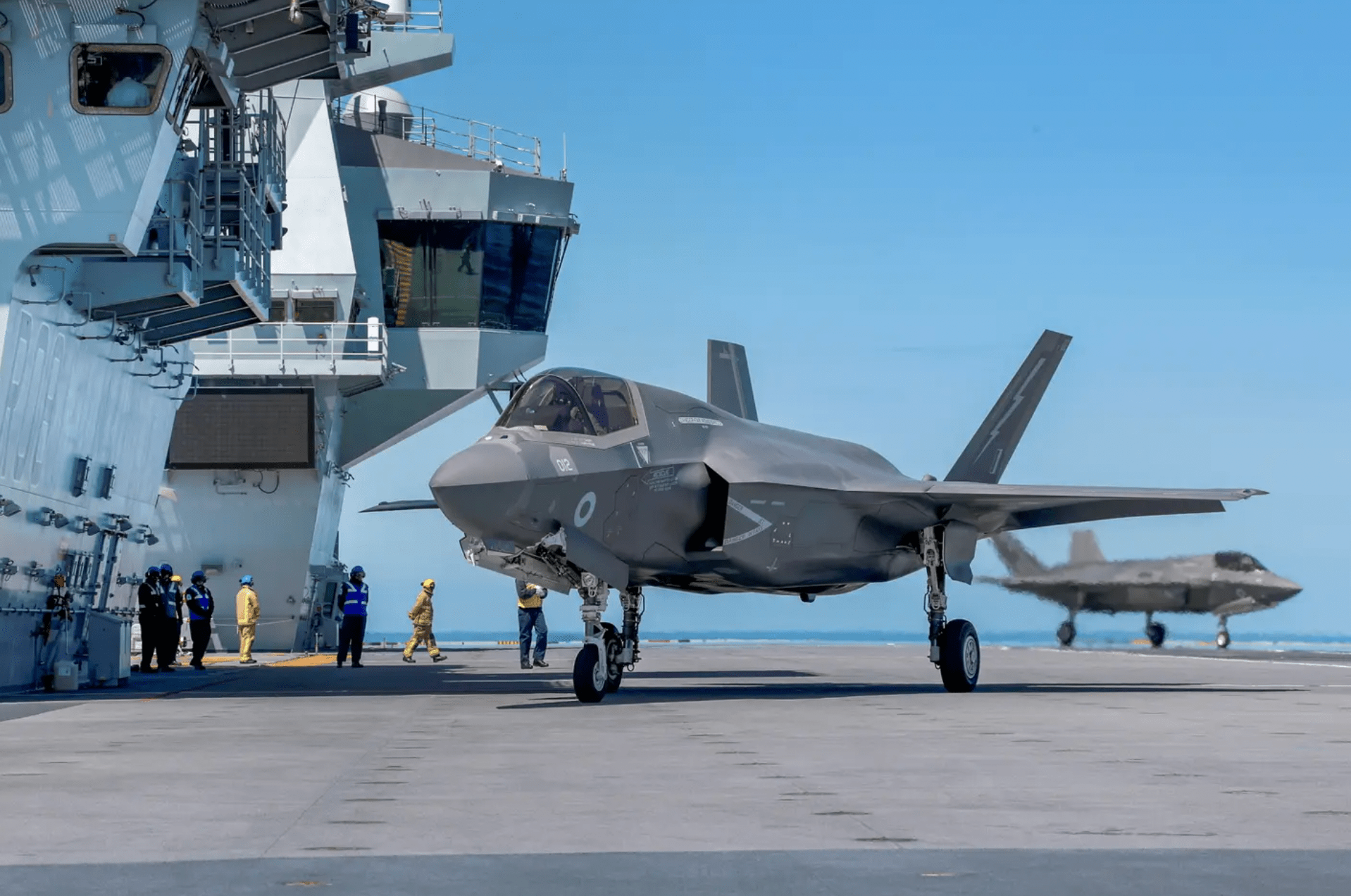

A video from QinetiQ shows that the Jackdaw is intended for ground launch, with containerized drones blasting off from rail-type launchers, as well as maritime operations, using similar launchers from the deck of a carrier. This is especially interesting considering the U.K. Royal Navy’s expanding plans for drone operations from its two Queen Elizabeth class carriers. Previous experiments in this area have also included Banshee drones launched from these vessels.

A “disposable” drone, if that can be achieved, would lend itself well to all of these missions, which demand close proximity to hostile air defenses and other threats.

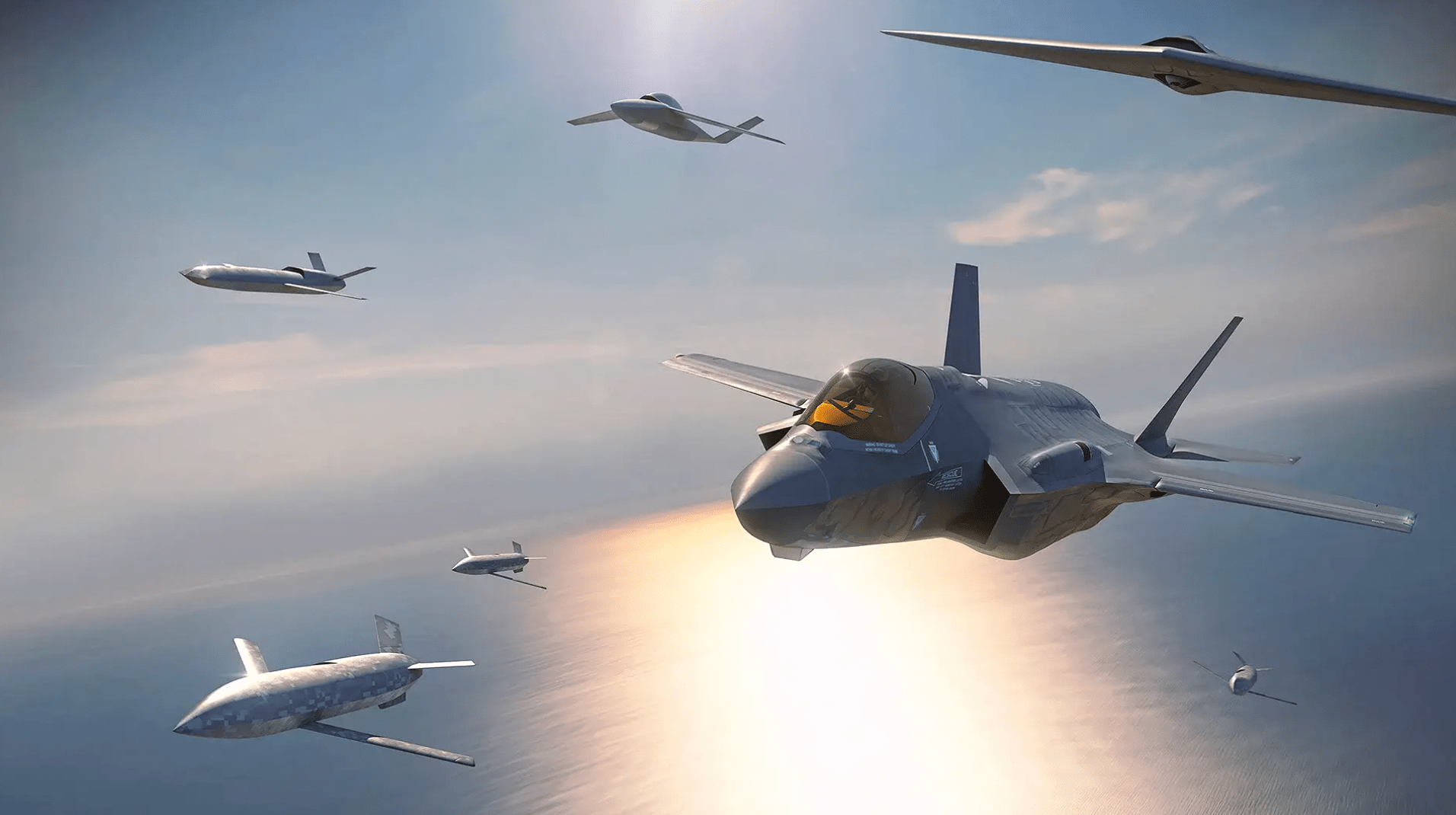

The Jackdaw is also intended to perform missions of this kind as an adjunct to traditional crewed aircraft, flying collaboratively and autonomously as part of a crewed-uncrewed teaming concept. This, again, is another key driver behind many drone programs in the United States, most notably the U.S. Air Force’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) concept, which aims to have a fighter pilot go into battle accompanied by as many as five drones under his or her limited control. Again, these drones will be expected to gather intelligence, jam communications, or serve as decoys. CCA also calls for drones that can launch their own weapons, a facet that is not currently mentioned for Jackdaw.

As well as the planned low price point that should allow the Jackdaw to be considered disposable, this should also allow it to be fielded in considerable numbers, firmly ticking the “combat mass” box. In the United Kingdom, crewed combat aircraft numbers have steadily declined since the end of the Cold War, with the Typhoon fleet set to be reduced and the total number of F-35B stealth jets planned to be bought still very much unclear. This makes the potential of a collaborative drone especially attractive.

As QinetiQ describes: “Jackdaw will enable our armed forces to reduce operational risk and increase combat mass by rapidly deploying large numbers of UAS in scenarios currently dependent upon small numbers of expensive crewed aerial platforms. By teaming large numbers of Jackdaw with other UAS and crewed platforms, mission effectiveness will be enhanced, the threat to human lives mitigated, and the cost of conducting operations significantly reduced.”

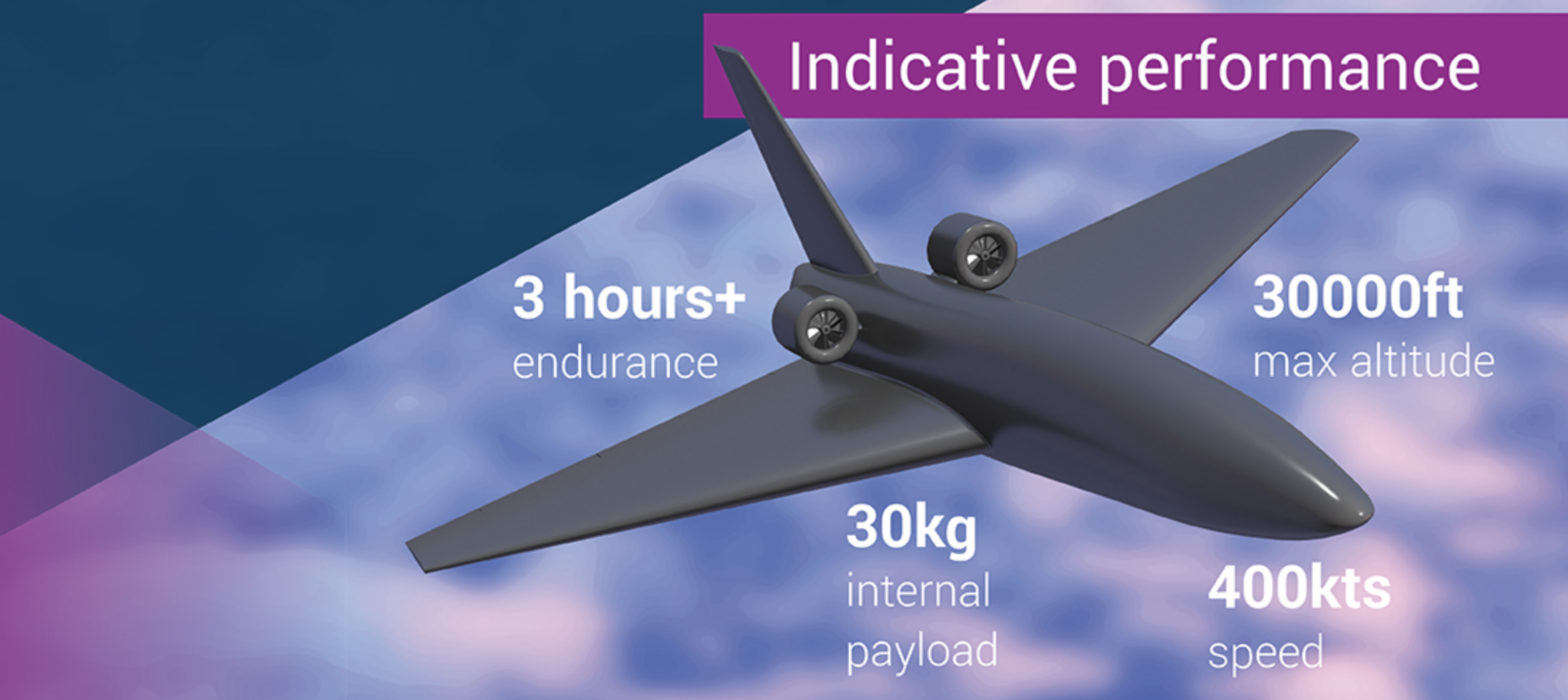

QinetiQ has also published some of the likely specifications for the Jackdaw, including a maximum speed of 400 knots and an altitude of 30,000 feet. With an internal payload of 66 pounds, it’s expected to have an endurance of at least three hours. The speed part is interesting as this would not allow it to keep up with fighters in a tactical environment. Mission planning would need to be intricate to make sure they are available where they are needed during specific periods missions where teaming is paramount.

The company sees Jackdaw ultimately forming part of “a family of UAS which will operate together seamlessly and coherently,” which may well also point to potential future integration in the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) architecture.

The British FCAS, not to be confused with the European program of the same name, has the Tempest crewed sixth-generation fighter as its centerpiece. However, it also includes other complementary technologies, among them ‘loyal wingman’ type drones and a new generation of air-launched weapons and sensors.

Beyond the U.K. Armed Forces, QinetiQ is hopeful that the Jackdaw will find foreign interest, too, and it will be designed to allow “easy adoption for allied countries,” including an “autonomous goal-based mission management system [that] is intended to integrate with NATO and allied open architectures, ensuring interoperability with existing and future crewed and uncrewed systems,” according to Mick Andrae, Global Campaign Director, Robotics & Autonomous Systems, at QinetiQ.

QinetiQ says that the Jackdaw design program “is well underway, currently developing autonomous mission management and human-machine teaming capabilities, with platform development phases commencing soon.” According to the company’s current plans, the Jackdaw should be available for service from the mid-2020s. After that, an “iterative development roadmap” should add further capabilities over time.

The Jackdaw is clearly a far more modest proposition, in terms of scale and all-round capabilities compared to larger ‘loyal wingman’ drones like Boeing Australia’s MQ-28 Ghost Bat, or even Anduril’s Fury drone, which is planned to carry more than 10 times the payload of the British UAS, and which you can read about in-depth here.

On the other hand, its more modest specifications are offset by what the company promises to be a “very low-cost” drone and one that should still be able to fly combat support missions in highly contested environments — whether it manages to survive or not. QinetiQ also expects the Jackdaw to serve as an adjunct to both crewed aircraft and larger drones, in the category of the Ghost Bat, for example.

Clearly, the United Kingdom, like many other nations, is investing heavily in the potential of uncrewed assets as it seeks to optimize its future air combat fleet and optimize its capabilities. We already know that drones will be a central part of the FCAS ecosystem and there have been various other efforts to explore potential future drone designs.

The U.K. Royal Air Force has its own drone initiative known as the Lightweight Affordable Novel Combat Aircraft (LANCA) program, which is looking into a range of future kinds of drones. At one stage, this included Project Mosquito, which planned to test a ‘loyal wingman’-type drone capable of working together semi-autonomously with manned aircraft, but this was canceled last year.

Weeks later, BAE Systems revealed concepts for two new types of UAS. One of these is a relatively small drone capable of operating either individually or as part of a networked swarm and is fairly similar to the Jackdaw in terms of concept and planned specifications. The second is larger and more in line with various lower-tier uncrewed combat air vehicle concepts that other companies have put forward in recent years. You can read more about both here.

BAE Systems’ “agile and affordable” drone concepts to meet the demands of a “complex and rapidly evolving battlespace.” The smaller drone in the foreground is broadly comparable to the Jackdaw. BAE Systems

Without a doubt, the United Kingdom is still very much weighing up how best to use drones in the future, although at least there seems to be growing clarity about the kinds of missions they might fly. Still to be determined, meanwhile, is the size and performance of these drones, what they should cost, and the degrees of autonomy they should have.

With that in mind, the Jackdaw does, at the very least, provide an interesting insight into one British option for the kinds of uncrewed aerial system that will be expected to not only operate as swarms but also accompany crewed fighters in future air warfare scenarios.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com