Life in the Navy can be stressful during the best of times, with rough seas, long hours, and cramped conditions for sailors to deal with. However, there are probably few moments more stress-inducing than when sailors are told to brace for impact due to inbound missiles that could immanently rip into the ship and detonate.

Most all of us will thankfully never have to experience what it’s like being locked in a steel container full of explosive material while missiles are flying directly at said container, which has nowhere to hide on the open ocean. That’s why the video footage captured from inside the World War II-era refitted Iowa class battleship USS Missouri, during the latter stages of the Gulf War, is so intriguing. It allows us to see exactly how the crew reacted to incoming Iraqi Silkworm anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs).

This was not a drill.

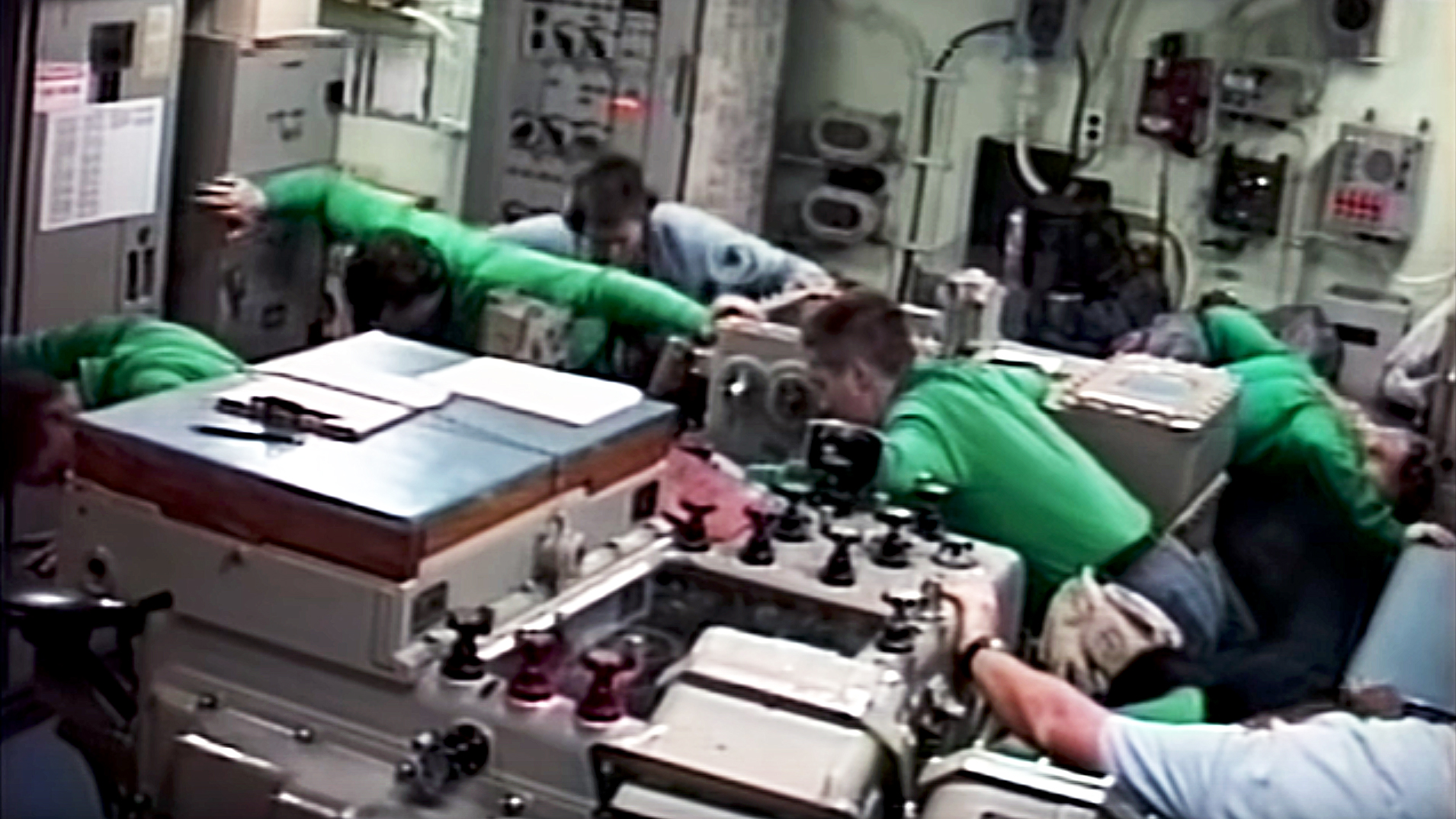

The footage was captured from inside Missouri’s main battery plotting room — the ship’s fire control center for its massive 16-inch guns — on February 25, 1991, off the coast of Kuwait.

Missouri, which was reactivated and modernized in the mid-1980s, arrived in the Middle East in early January 1991 in response to growing tensions following the decision of Iraq’s then-President Saddam Hussein to invade Kuwait in August of 1990. In terms of upgrades, Missouri boasted 16 RGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missiles, eight Mk 143 Armored Box Launcher mounts for 32 BGM-109 Tomahawk land attack cruise missiles, and four 20 millimeter Phalanx CIWS rotary cannons. The vessel also received radar and fire and control system upgrades, as well as improved electronic warfare capabilities.

At the time the video was captured, coalition forces were pushing ahead with the ground war in Kuwait during the final phase of Operation Desert Storm. As part of the deception, Missouri was shelling Kuwait’s coastline with its massive deck guns, harassing Iraqi forces in a feinted amphibious landing, which began at around 12:55 A.M. on 25 February.

Just after Marine Corps helicopters turned around from flying towards Kuwait’s coast, at around 4:52 A.M., Iraqi forces fired two Silkworm ASCMs at Missouri. The launches were visually observed by an A-6 Intruder, which reported two distinct plumes from the area of al-Fintas — the northernmost Silkworm site south of Kuwait City. One of the ASCMs quickly fell into the sea, but the other proceeded towards Missouri.

The moments onboard the ship following the missile being spotted are documented clearly in the video. In the footage, we can hear the ship’s crew being told to brace for impact. “Missile inbound… brace for shock.” With the missile reportedly approaching the starboard side, the sailors no doubt feared the worst and braced for that vector of attack. A moment of laughter punctures the tension shortly after this in the video, when a voice over the intercom asks “control… do you have the missile visually?” to which the response “I’m not looking for it.”

Fortunately, HMS Gloucester, which was serving as an escort for Missouri, detected the inbound missile via radar and fired two Sea Dart surface-to-air missiles to intercept it. Significantly, this was the first time a sea-launched surface-to-air missile had ever successfully intercepted an incoming missile in combat. Missouri also fired countermeasures, which confused the Silkworm’s guidance system. Missouri’s four Phalanxes also were switched from standby to auto-engage, however, they did not fire. The Oliver Hazard Perry class frigate USS Jarrett, which was also supporting the mission, did not fire on the missile with its Phalanx as it was outside of the range envelope. The men were subsequently instructed to “relax brace.”

At around the six minute mark in the footage captured on February 25, the frame shifts, showing the sailors wearing anti-flash hoods while others are visibly carrying anti-flash gloves. At the 18:30 mark, the men are instructed to don their gas masks due to a suspected gas or chemical attack. Although this footage appears to be part of the same series of events, it actually depicts a second incident that took place later in the afternoon on February 25.

At that time, Missouri was continuing to bombard targets ashore. Although HMS Gloucester had since departed, Missouri was supported by USS Jarrett, the minesweeper HMS Atherstone, and the destroyer HMS Exeter.

Upon seeing smoke from a fire ashore, the result of Iraqi troops dynamiting an oil well, Exeter informed the other ships that an Iraqi missile was likely inbound. The sailors were once again instructed to brace for impact.

Missouri deployed chaff countermeasures, which fell between it and the Jarrett. Jarrett’s Phalanx, which had already been set to auto-engage, locked on to the countermeasure chaff clouds and fired. Missouri ended up getting sprayed by 20mm cannon fire as a result. However, the Navy’s official statement on the event, released six and a half months after Operation Desert Storm ended, notes that the vessel only suffered “superficial damage.”

After what must have felt like an eternity, the sailors aboard Missouri were instructed to relax their brace, but continue to put on their protective over garments. Shortly after the men are almost all fully kitted out in the gear, the all clear is given. “All stations this is the XO [Executive Officer] relax the gas masks. From what I understand what we got [sic]… there’s no reported gas now, and there’s no reported missile activity.”

The relief on the sailors’ faces at that moment is clear to see. Although Iraq did not use chemical weapons during the Gulf War, fears that Iraqi forces would use them were rife across the services.

Watching the chain of events of the day unfold on video — just one microcosm of a ship that housed over 1,500 sailors, — is obviously quite something, but it only goes so far to suggest what may have been going on inside the men’s heads at the time. Bill Genereux, a professor of Computer & Digital Media Technology at Kansas State University who worked on the systems that aimed Missouri’s guns, describes what it was like being in the battery plotting room that day:

“This memory [aboard Missouri on February 25] is forever embedded in my memory. If you have ever come face to face with your own mortality, perhaps through an accident or a close-call or, heaven forbid, the loss of a close loved one, you know these days.

I was deep inside of an armored WWII battleship. The plotting room is one of a battleship’s ‘vital organs’ so to speak. It is the brains to the ship’s brawn, the 16″ guns. Without the computer equipment in this space, the ship cannot fight, so it is located deep inside the armored belt, right next to the engine spaces, meant to be safe from… shells and torpedoes. Even so, with a missile bearing down on you and you can do nothing but stand there and take whatever is coming, you have to wonder if this could be the end?

Fortunately, our battlegroup had some missile destroyers along with us riding shotgun, and the HMS Gloucester shot down the one that came nearest to us. I’ll never forget the name of that ship either.

Later in the video, you can see us putting on gas masks because we were warned that a gas attack was imminent. Missiles, now gas? At that point I was wearing a little protective box on my head, inside of a bigger protective box – the plotting room, inside of a bigger box – the armored belt, inside a still bigger box floating in the ocean – the battleship. Claustrophobia anyone?”

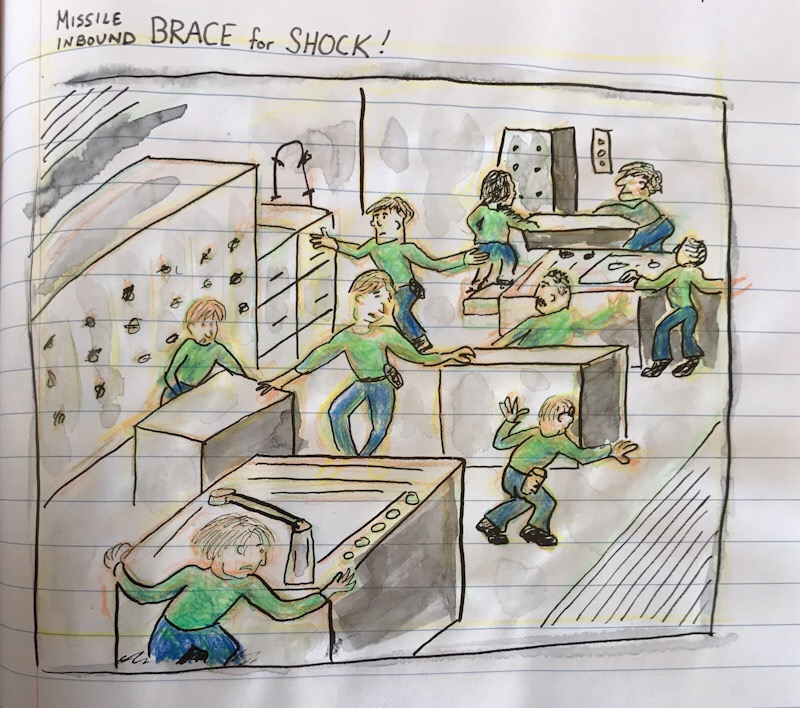

Genereux has also produced illustrations of the event, one of which can be seen below.

Shortly after the events of February 25, 1991, and after a 100-hour ground operation, the Gulf War came to a close. In March of 1992, amid Navy budget cuts and the absence of a perceived threat from the Soviet Union due to the ending of the Cold War, Missouri was decommissioned. Today she sits as a museum ship in Pearl Harbor right next to the USS Arizona memorial.

Altogether the footage, and Genereux’s testimony, provide truly remarkable insights into how sailors aboard Missouri responded to a direct threat from an incoming anti-ship missile. In the years since, these weapons have proliferated even to non-state actors and are a bigger threat than ever before. Even just seven years ago, attacks on U.S. warships by Silkworm missiles fired by Houthi forces in Yemen likely resulted in very similar scenes. In a Pacific fight against an adversary armed to the teeth with far more advanced anti-ship missiles of many types, these intense vignettes could play out with alarming regularity.

Contact the author: oliver@thewarzone.com