The U.S. Army has fired an Army Tactical Missile System short-range ballistic missile, or ATACMS, in Australia for the first time. The launch was part of the Talisman Sabre 23 large-scale exercise going on currently in that country. This is a glimpse of things to come as the Australian armed forces are now set to acquire these hard-hitting weapons.

There has been a resurgence of interest in ground-based standoff strike capabilities across the U.S. military in recent years, particularly in the context of a potential future high-end conflict against China. ATACMS, specifically, previously something of an obscure weapon in the American arsenal, is now a common topic of discussion in light of persistent calls to send them to help Ukraine in its fight against Russia.

The U.S. military announced the ATACMS shot today, but the actual firing took place last week. An M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) launcher from the Army’s 17th Field Artillery Brigade actually fired the missile. A U.S. Air Force MC-130J Commando II special operations tanker/transport aircraft helped move the HIMARS rapidly to its firing location. Elements of the U.S. Marine Corps and the Australian military also supported the live-fire training event. A total of 30,000 personnel from 13 nations in total are taking part in the overall exercise, which began on July 22 and is set to wrap up on Friday. This is the 10th iteration of Talisman Sabre, a biennial event that started in 2005 and was originally just a U.S.-Australia affair.

“So the Air Force allows us to load up on their birds to get to where we need to be and to put our HIMARS in a position that we can provide the long-range accurate fires and destroy the target,” 1st Lieutenant Joseph McCrystal said in a video about the ATACMS launch seen in the Tweet below. HIMARS offers you a long-range capability with speed, accuracy, and precision.”

The U.S. Army and Marine Corps have been ATACMS users for decades now. For Australia, acquiring these weapons would give its armed forces an additional option for striking static targets accurately and at standoff ranges.

HIMARS was specifically designed to be transportable using C-130 Hercules-series cargo aircraft and otherwise have good cross-country mobility. This could be extremely valuable for Australia, where just moving assets across the country, let alone elsewhere in the Pacific region, requires significant logistical effort. As part of the ATACMS launch at Talisman Sabre 23, the HIMARS launcher was flown from eastern Australia to the Northern Territory in the north central part of the country. This is something Australian Army Brigadier Damian Hill, the Talisman Sabre 23 Exercise Director, described in the video seen earlier in this story as “practicing logistics [at] its very hardest.”

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) already operates its own C-130s and is now set to greatly expand its Hercules fleet in the coming years. The Australian military is working to increase its long-range strike capabilities overall, including with the planned acquisition of air-launched AGM-158B Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile-Extended Range (JASSM-ER) and sea-launched Tomahawk cruise missiles.

When it comes to the actual capabilities of the ATACMS on display at Talisman Sabre 23, the U.S. military said it was an MGM-140 type, but did not specify a particular variant.

However, a clip in the footage above and accompanying pictures of the missile actually impacting Bradshaw Field Training Area in Australia’s Northern Territory indicate that it was a version with a unitary high-explosive warhead. The missile also reportedly flew approximately 260 kilometers (161.5 miles) to the target area. This all points to the weapon actually being an MGM-168A, which was originally designated as the MGM-140E.

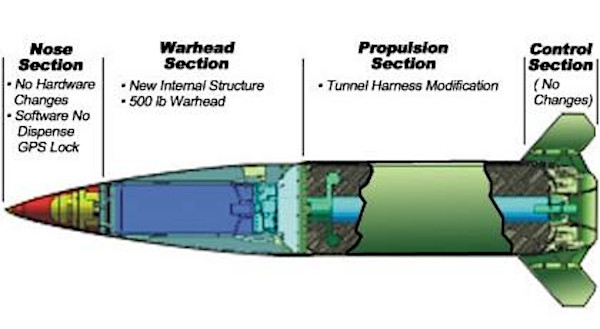

Also known as the ATACMS Block IVA, the MGM-140E/MGM-168A was introduced in the early 2000s and has a 500-pound-class high-explosive warhead, as well as a stated maximum range of 300 kilometers (186 miles). The missile can be used to strike static fortified targets, as well as softer ones in the open. This is the variant that Australia is expected to buy.

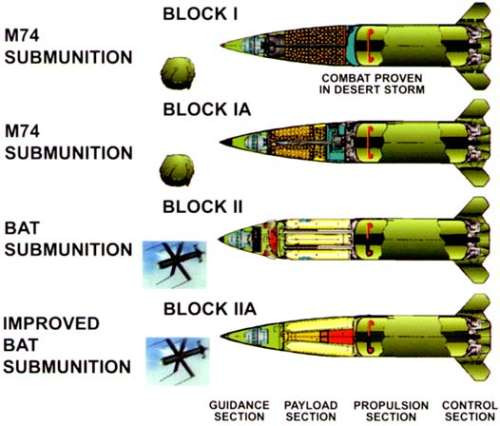

The original Block I MGM-140A, which first entered service with the U.S. Army in 1991, had a warhead consisting of 950 small submunitions and a range of around 165 kilometers (102 miles). The Block IA MGM-140B, which arrived in the late 1990s, had a reduced load of 275 submunitions, but a longer maximum range of 300 kilometers (186 miles). The B variant also introduced a new GPS-assisted inertial navigation system guidance package, a capability that became a standard feature on all following versions.

The MGM-140C variant, also known as ATACMS Block II, also had a submunition warhead, but one consisting of 13 small precision-guided Brilliant Anti-Tank (BAT) glide bombs. It also had an even shorter maximum range than the A version, topping out at around 140 km (87 miles). The MGM-140C, which was redesignated the MGM-164A, was never fielded in large numbers and it’s not clear if the planned MGM-140D, possibly an upgraded B or C variant, ever moved beyond the drawing board. BAT subsequently evolved into the air-launched GBU-44/B Viper Strike.

As short-range ballistic missiles, all ATACMS variants reach relatively high speeds as they come down in the terminal phase of flight. This can make it a real challenge for enemy air defenses to engage them compared to other kinds of missiles, including some subsonic air-breathing cruise missiles. When it comes to the MGM-168A, specifically, that terminal speed helps it burrow deeper into hardened targets.

The primary launch platforms for ATACMS are the M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) and the M142 HIMARS, which can be loaded with two or just one of these missiles at a time, respectively. Those launchers can also fire 227mm artillery rockets, including precision-guided types.

The ATACMS missile is currently the longest-range surface-to-surface weapon in full operation service in either the Army or the Marine Corps. However, the Army is moving to replace it with a newer and much longer range design known as the Precision Strike Missile (PrSM), the initial variants of which are expected to be able to hit targets at least around 500 kilometers (403 miles) away, if not further.

The Army is planning to acquire additional PrSM variants or derivatives with the ability to hit targets out to ranges of 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) or more, as well as ones with additional seekers allowing them to engage moving threats like large ships.

The PrSM is designed to be fired from the same launchers as ATACMS. This, in turn, would make it relatively easy for the Marines, and other existing and future MLRS/HIMARS and ATACMS operators like Australia, to field these weapons, as well.

The maximum range of all U.S. ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles had previously been limited by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF, with Russia, which collapsed in 2019. Since then, the Army and the Marines have been moving toward fielding a variety of other long-range ground-launched missiles, including Naval Strike Missile (NSM) anti-ship cruise missiles, variants of the Tomahawk cruise missile, multi-purpose Standard Missile 6s (SM-6), and new hypersonic types. The Navy has also been experimenting with a new ground-based long-range missile capability.

The specter of a potential future high-end conflict with China, which has a large and diverse land-based missile arsenal, has been a major driver of U.S. interest in new long-range ground-launched strike capabilities. The Army’s Pacific-facing 17th Field Artillery Brigade is a centerpiece in these efforts and already includes the first unit the service expects to arm with its Dark Eagle hypersonic missiles.

The U.S. military is very interested in being able to base its new long-range strike capabilities forward across the Pacific where they would be in range of Chinese targets, or at least be able to readily deploy them to those locations. However, many U.S. allies and partners, including Australia in the past, have expressed reticence to allowing any permanent stationing of these weapons on their territory. Regardless, ATACMS’s limited range means that it would be difficult to find locations where it could be forward deployed within reach of China, which is one of the reasons for the development of PrSM.

Concerns about China’s rising military prowess have prompted new engagement with allies and partners, especially Australia, which is working with the U.S. military on future hypersonic missiles, among other things. It was just recently announced that the U.S. and Australian governments would move toward greater cooperation in this realm, including production in the latter country of American-designed munitions. The initial focus of that specific initiative will be on producing 227mm Guided Multiple Launch System (GMLRS) precision-guided artillery rockets and 155mm artillery shells.

American defense and security ties with Australia, as well as the United Kingdom, have significantly expanded in recent years as part of the trilateral Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) pact, as well. A plan to help the Australian Navy acquire a nuclear-powered, but conventionally-armed submarine force, which will include U.S.-made Virginia class boats and examples of all-new design, is a major component of that deal. The U.S. military is set to increase its rotational force posture in Australia as part of the agreement, too.

ATACMS, more broadly, has become something of a household name in the past year or so thanks to persistent calls from Ukrainian officials and their supporters elsewhere around the world for deliveries of these missiles to help the war effort against Russia. Ukraine’s armed forces have received HIMARS and MLRS launchers as part of previous aid packages from the United States and other countries, but have so far only gotten guided 227mm artillery rockets to go with them. The U.S.-supplied HIMARS launch vehicles have reportedly been specially modified to prevent them from being able to launch ATACMS missiles.

Advocates for sending ATACMS to Ukraine say it would give the country an important additional tool for conducting strikes on high-priority static Russian targets, like hardened command centers, bridges, and supply depots, deeper behind the front lines. The U.S. government has so far rebuffed those requests, citing concerns about potentially provoking a new degree of escalation from Russia, as well as about the size of its own stockpile of these weapons.

The validity of the fears of an especially serious Russian response is very much up for debate, especially given the long-range strike weapons Ukraine has already gotten from the West, including Storm Shadow cruise missiles from the United Kingdom. Additional concerns about operational security may be somewhat mitigated by the fact that ATACMS is something of a known quantity after some three decades of service, including combat use during the First Gulf War in 1991 and the invasion of Iraq in 2003

The issue of the total U.S. stockpile of these missiles, which could be an important tool in a future major conflict, is unquestionably real and is something The War Zone has highlighted in the past. How many ATACMS the U.S. military currently has is not clear, but only around 4,000 in total across all the variants have been made to date, a recent report from The Washinton Post says, citing data from the current manufacturer Lockheed Martin. The U.S. military is understood to have expended around 600 ATACMS in combat, More of the missiles have been fired during training events like Talisman Sabre 23, along with shows of force in South Korea.

In addition, the U.S. Army, at least, has stopped buying any additional examples as it looks to transition to the PrSM. The service has reportedly converted some, if not all of its remaining stockpile to MGM-168As, as well, as part of a U.S.-wide shift away from controversial cluster munitions.

Lockheed Martin is still making ATACMS missiles, but for export customers like Australia. What capacity the company might have right now to fulfill significant rush orders for Ukraine is unknown.

Whatever the case, the ATACMS launch during Talisman Sabre 2023 underscores that these missiles are still currently an important part of the U.S. military’s higher-end arsenal.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com