A new mobile ground-based air defense system centered around AIM-132 ASRAAM (Advanced Short-Range Air-to-Air Missile) has emerged in Ukraine. It takes the AIM-132, a hugely capable weapon, and adapts it for surface launch.

The ad-hoc system is another example of the wide variety of advanced weapons that have been supplied to Kyiv by the United Kingdom. It will help meet a dire demand for short-range air defenses (SHORADs) needed to tackle a resurgent Russian aerial threat on the frontlines. It’s also just the type of system The War Zone said was needed ASAP back in June as the counteroffensive began to unfold

A story about Ukraine’s air defenses in The Times newspaper today includes a photo — seen also at the top of this story — of a 6×6 Supacat all-terrain truck chassis, with a twin-rail launcher for a pair of ASRAAMs mounted at the rear. Toward the cab, there also appears to be a sensor turret mounted on a pylon, which is possibly telescopic so that it can be raised high above the truck. This is likely an electro-optical/infrared sensor turret, which could be used for target cuing. Potentially, it could also have as short-range radar function.

According to The Times, who spoke to an unnamed Ukrainian lieutenant colonel serving in Kyiv’s air defense command, the U.K. Ministry of Defense has supplied “a handful of Supacat trucks rigged by British engineers to fire ASRAAM.” The story adds that these systems “are deployed primarily to intercept swarms of Russia’s Iranian-supplied Shahed suicide drones, but some of the systems are also supporting Ukraine’s counteroffensive.”

The high-mobility capability of the Supacat means that it’s able to operate close to the front lines, as well as in defense of key static targets. In this way, it “can enter an area where Russian attack helicopters are operating, shoot, and move away.” Since the launch of the Ukrainian counteroffensive, around two months ago, Russian attack helicopters have established themselves as one of the preeminent threats as The War Zone was one of the first to report. In our original story, we noted that short-range air defense systems that are highly mobile would be critical in countering the rotary-wing threat.

“Unlike other systems like Starstreak, the ASRAAMs do not require a line of sight and can lock onto targets themselves if fired into their vicinity,” the article adds, a reference to the infrared guidance system the missiles use, which provides a ‘fire and forget capability.’

At this point, it’s unclear what type of sensors, beyond the EO/IR turret seen on the truck, can be used to detect and acquire the targets in the first place, although it’s certainly possible that targeting cues are provided by other platforms. Importantly, the ASRAAM is also capable of being used in lock-on after launch (LOAL) mode, meaning targeting data can also be sent to the missile, via datalink, once it has left the rail. This would be key for a system like this. Even just the EO/IR turret could provide basic targeting vectors for the missiles to lock onto once they have left the rail and the target has entered their high off-boresight (HOBS) seeker’s acquisition envelope.

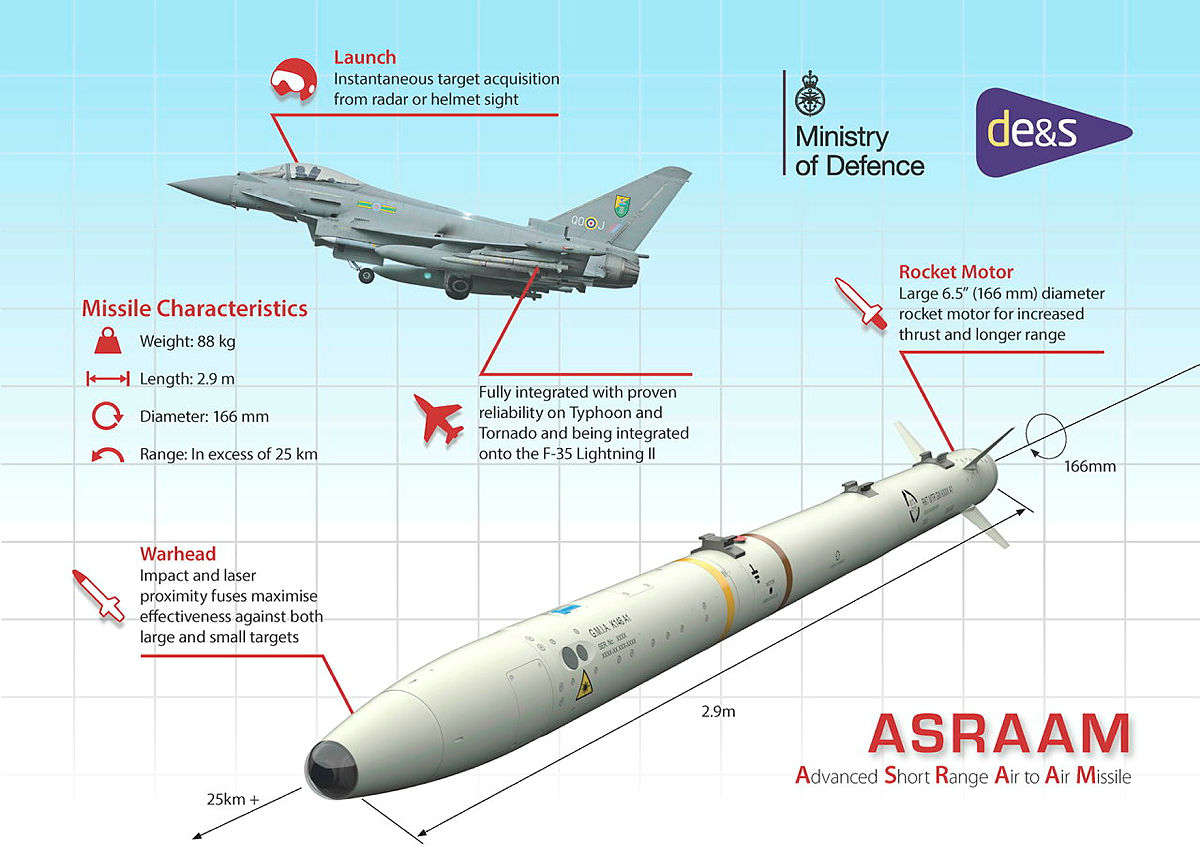

Weighing a little under 200 pounds, and measuring 9 feet 6 inches long, the ASRAAM has a diameter of 6.5 inches. It is widely analogous to the AIM-9X Sidewinder, but with some performance differences.

When air-launched, targets can reportedly be engaged at a distance of more than 15 miles, although unconfirmed accounts assess ASRAAM range as much greater than this, perhaps as far as 31 miles. Again, this is a range after launch from a fast-moving aircraft, at high altitude, maximizing kinematic performance, and the distance would be reduced dramatically in a surface-launched application.

Interestingly, the concept of a surface-launched version of the ASRAAM missile — which otherwise arms aircraft, including Royal Air Force Typhoon fighters — has helped realize the British Army’s Sky Sabre air defense system, which you can read more about here.

The Sky Sabre is armed with MBDA’s Common Anti-Air Modular Missile, or CAMM, also known as the Land Ceptor. The same CAMM missile is also used in naval applications — including aboard U.K. Royal Navy warships — as the Sea Ceptor. The CAMM is derived from the ASRAAM but, although it uses the same rocket motor, warhead, and proximity fuse, the new missile is fitted with an active-radar seeker.

The Supacat-based system for Ukraine is notably less sophisticated than the Sky Sabre, befitting the apparently rapid timeline for its development, to meet an urgent operational requirement.

Ukraine’s critical need for ground-based air defense systems, especially more advanced ones, is something that The War Zone has addressed on more than one occasion in the past.

It’s also a reality that the colonel who spoke to The Times also reflected upon.

“The shortage of missile supplies is also threatening to derail Ukraine’s counteroffensive, he added, saying the army had run out of munitions needed to dislodge the Russians at the end of May, forcing troops to ‘storm fortified points head-on.’”

While this quote doesn’t specify the munitions involved, it may well relate to a claim included in a leaked Pentagon document earlier this year. In it, officials assessed that Ukrainian air defenses assigned to protect troops on the front line would “be completely reduced” by May 23, due to the rate at which they were burning through Soviet-era munitions stockpiles.

Whatever the case, Ukraine still has an enormous requirement for ground-based air defense systems, as well as the stocks of missiles needed to arm them, which are being consumed at a prodigious rate.

In particular, these kinds of weapons are needed for the ongoing counteroffensive. As we have explored in the past, without sufficient ground-based air defenses at the front, Russian air power will be much less constrained in how it operates over the forward edge of the battlefield, with potentially disastrous consequences for Ukrainian troops on the ground.

In this scenario, the highly mobile Supacat/ASRAAM combination appears to be an excellent fit for those requirements. With ample stocks of ASRAAMs in the UK’s inventory, these highly mobile SHORADs can be kept fed, as well. It’s unclear what happened to Australia’s stockpile of ASRAAMs after the type was retired with the F/A-18A/B or if those weapons could be made available to Ukraine.

While the numbers of these new systems appear to be strictly limited, it will be interesting to learn more about their capabilities and what kind of impact they are having in the conflict going forward. But above all else, they are another example of how the ingenuity of rapidly adapting advanced Western weaponry for Ukraine’s use on the battlefield is really accelerating.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com