The Army recently flew Sikorsky’s optionally manned Black Hawk helicopter for an hour without pilots in the cockpit or direct human control, instead allowing the aircraft’s robotic brain to operate the helicopter during a tech demonstration in the Arizona desert.

As part of the more extensive Project Convergence experimentation program, the Optionally Piloted Vehicle, or OPV Black Hawk, and several other technologies were recently tested by Army Futures Command officials for inclusion in an eventual suite of systems that will autonomously resupply forward deployed troops around the clock in all weather.

Sikorsky and the Army have been conducting tests in support of developing a fully autonomous and/or remotely piloted UH-60 Black Hawk for years. The OPV Black Hawk initially carried safety pilots in the cockpit. In February, pilots were removed from the test helicopter to demonstrate that Sikorsky’s Aircrew Labor In-Cockpit Automation System, or ALIAS, can fly the helicopter without a human. Sikorsky released the below video on the occasion of the first “uninhabited flight.”

ALIAS is designed to assist aircrews performing complex aviation missions. It is meant to function as a sort of digital copilot to reduce pilot workload and decision fatigue while improving safety in piloted mode. The system’s autonomous control can be dialed up or down depending on mission requirements and should eventually be retrofittable into any legacy rotorcraft. ALIAS is a project helmed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) that uses Sikorsky’s MATRIX autonomy flight control system. Sikorsky and DARPA plan to release more information about the so-called ‘gateway’ demonstration flights in November, according to a Sikorsky spokesperson.

“Sikorsky and DARPA flew an uncrewed Black Hawk helicopter to show how the U.S. Army’s existing and future fleet of piloted utility helicopters could also resupply forward forces in contested battlespace autonomously,” a Sikorsky spokesperson told The War Zone in an email. “The autonomous flights to date demonstrate missions to carry cargo externally on a sling beneath the aircraft; evacuate a casualty (manikin) on a litter; and carry inside the aircraft cabin real and simulated blood more than 80 miles without loss or degradation of product.”

As seen in the photo at the top of this story, the aircraft flew for one hour with no human pilots in the cockpit.

Now that it has demonstrated pilotless flight, the Army doesn’t want to proceed with the technology if it is running in any other mode, according to Lt. Gen. Thomas Todd, deputy commander for acquisition and systems and chief innovation officer at Army Futures Command. The Army’s OPV, a UH-60A retrofitted with ALIAS, was most recently trialed at Yuma Proving Ground, Arizona, during the Project Convergence 2022 Technology Gateway.

“Last year, we had a safety pilot in the Black Hawk at Project Convergence. My requirement this year was don’t even bring it if it can’t be flown fully autonomous,” Todd said during a call with reporters on Oct. 17. “We have to push ourselves to take steps. The beauty of the industry partner … is they were able to execute the mission at ranges that we had not previously seen with payloads we had not previously seen.”

Project Convergence is an annual “campaign of learning” in which Futures Command employs relatively mature technologies in real-world combat scenarios to see what works. The idea is to quickly vet promising new weapons, equipment, and software and transition those that offer an operational advantage to programs of record. New in 2022, Gateway is a pre-exercise round of testing for new technologies to enter the Project Convergence Pipeline, said Maj. Gen. Miles Brown, commanding general of the Army’s Combat Capabilities Development Command (DEVCOM).

Futures Command hosted the Project Convergence 2022 Technology Gateway at Yuma Proving Ground (YPG) Arizona from Sept. 19 to Oct. 18. The larger Project Convergence has commenced at Camp Pendleton and Fort Irwin in California.

The OPV Black Hawk participated in the 2021 Project Convergence, performing combat resupply as part of a simulated aerial assault. During that exercise, the aircraft was crewed by safety pilots who did not handle the controls but were on board to take over in case of emergency. It is scheduled to participate in the PC22 exercises, this time without safety pilots aboard.

While both the Army and Marine Corps see promise in autonomous systems for cargo missions, there is still hesitancy at the notion of flying human passengers without pilots in the cockpit. Service leaders acknowledge the utility of evacuating wounded soldiers from combat zones with autonomous systems, but have not crossed the line to transporting troops with drones just yet.

“It gives us the ability, at an integrating event, to do some collaboration on what are the types of technologies that we’ll be able to integrate at future project convergence events, or in other system or technical experiments that we do across the army,” Brown said. “This gives us a bit of a farm team to start the conversation earlier. … What’s on the other side of this is more experimentation, more activity, and more opportunities to transition, as opposed to being just one discrete activity that happens, you know, once a year, or every other year or something like that.”

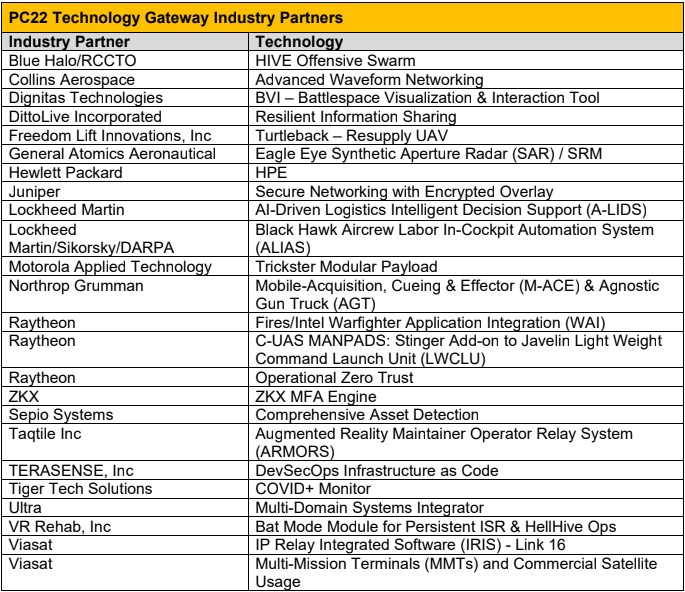

Dozens of technologies were tested at the Gateway exercise that recently concluded at Yuma, several of which were “autonomous activities that support that joint concept of contested logistics, or autonomous or semi-autonomous sustainment,” Todd said. A list of the companies that participated in the Gateway event and the technologies they demonstrated is below.

“This whole idea of being able to launch an aircraft in all weather in a contested environment, high threat environment and deliver key critical supplies for our soldiers in need is huge for us,” Todd said. “Sometimes with manned platforms, while we manage risks in an all-weather environment, it’s tough for us to take off in what we call zero-zero weather – zero ceiling and zero visibility.”

Without a crew on board, the risk calculation of taking off in adverse weather is very different, he said. The decision to send a Black Hawk full of food, ammunition, and other supplies to a forward-deployed unit during a bad storm is more easily made when no crew is on board.

The Army wants that and similar technologies capable of lifting heavyweight cargo – up to the 9,000-pound lifting capacity of a Black Hawk, at least – and carrying them to ranges outside the capability of human-crewed aircraft, Todd said. That includes maritime environments the Army will encounter in any conflict in the Asia-Pacific region. Todd called the OPV Black Hawk and other autonomous logistics systems “extremely exciting technology for various missions.”

“That’s the whole reason we’re on board is there are certain classes of supply that we need to lift to our soldiers at ranges and in contested environments, potentially maritime environments, that are greater than we’re used to fighting and deliver those supplies, hopefully ahead of time or at a minimum just in time,” Todd said. “We don’t want weather or the enemy to be an impediment to us achieving that in the future. That’s the reason the technology was tested here, but at the end of the day, it’s going to serve in many different arenas. The medical community is tremendously interested in this. Obviously, the logistics community is tremendously interested in this. I have no doubt there’ll be even more applications.”

Also tested during the Gateway event was a commercial vertical-takeoff-and landing drone called Turtleback built by Melbourne, Fla.-based Freedom Lift Innovations. The coaxial-rotor drone can carry up to 2,000 pounds of cargo using an electric-hybrid motor at ranges up to 250 miles, according to the company. It can cruise at 125 miles per hour and, depending on speed and load, can stay aloft for between three and 18 hours.

Without specifying which technology, Todd said autonomous systems at Yuma demonstrated the ability to deliver supplies to as many as 40 points of need simultaneously without the need for road or rail networks.

“These are real problems that we’re facing in this new kind of peer-to-peer competitor environment,” Todd said. “And somebody said, ‘We think we’ve got a concept that can go and lift the pallet the way you deliver it, the way you package things right now, and we’re going to build our system around it. Well, that’s music to our ears. You mean we don’t have to completely reconfigure ourselves to use it? What a great day.”

“That’s not a military company,” Todd added. “That’s a commercial company. They want to take the technology they’re doing in the commercial sector and see if it has an application here. I think that is just one example of how we have already won. Number one, our soldiers have won. Our nation is winning; our taxpayers are winning.”

The Army has long sought ways of removing troops from the drudgery of dangerous battlefield tasks like driving fuel convoys or flying resupply missions to soldiers in combat. Reliance on roads for fuel distribution in Iraq and Afghanistan made soldiers vulnerable to improvised explosive devices and ambush. Having learned that lesson the hard way, the Army began searching for autonomous ground systems like the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle and Robotic Combat Vehicle that would bring the unmanned capabilities so prevalent in the sky down to earth.

Marine Corps officials also have recognized the advantages of autonomous resupply. The service bought two Kaman K-MAX helicopters outfitted with autonomous flight control kits and used them successfully for a limited period in Afghanistan. The Marines also tested a similar capability to the OPV Black Hawk with a modified UH-1 and recently awarded a contract to Kaman for developing an uncrewed autonomous resupply rotorcraft called Kargo, which is similar in form and function to the Turtleback.

Army Chief of Staff Gen. James McConville laid out his vision of future combat, in which manned vehicles are preceded into combat by remotely operated counterparts in almost all scenarios.

“I see that, as we have unmanned aerial systems now, we’re going to also have unmanned ground systems,” McConville said recently at the Association of the U.S. Army’s annual convention in Washington, D.C. “We do a lot of aviation with manned-unmanned teaming. You’re going to see a lot of that being done on the ground. … We never want to see someone going through a minefield or going through roads with IEDs that has a manned vehicle in front. We can do that with unmanned capabilities.”

One of the significant requirements of the Army’s pending Future Vertical Lift effort is developing next-generation rotorcraft that are speedier than existing helicopters that are optionally manned. Flying a 12,000-pound UH-60 without direct human control is a lofty goal, but the OPV aircraft is proving that capability a reality. The technology is meant to be both scalable and platform agnostic, so pilots could be removed from other current and future rotorcraft designs.

But all told, an optionally manned Black Hawk could prove to be a massive deal all on its own.

Contact the author: Dan@thewarzone.com