Israel is in possession of arguably the most sophisticated multi-layered integrated air defense system (IADS) found anywhere in the world. As tensions grow around the ongoing Israel-Gaza conflict, concerns are mounting that a wider war could draw in Hezbollah, with its own giant arsenal that can strike deep into Israel, and perhaps also Iran, a major backer of both Hamas and, especially, Hezbollah. Were such a scenario to unfold, Israel would be hugely reliant upon its IADS for protection from thousands of incoming projectiles. So, it’s a better time than any to profile the primary weapon systems that comprise Israel’s highly unique aerial shield.

Editor’s note: This piece was finalized before the successful intercept of drones and cruise missiles launched from Iranian proxies in the Red Sea region and intercepted as the headed north, towards Israel, by the American destroyer USS Carney. You can read more about that incident in our coverage here, but it highlights how critical Israel’s air defenses are, especially if a multi-front war were to breakout, which could happen at any given time.

First, it’s worth looking briefly at the nature of the threats that the Israeli air defense system was developed to counter. On the one hand, Israel’s most immediate adversaries, namely Hamas and Hezbollah, have made significant advances in recent years in terms of expanding and improving their rocket and missile arsenals, presenting new challenges for the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

The sheer scale of the potential Hezbollah threat — more than 100,000 rockets of various types — provides a huge air defense challenge. As well as rockets, ballistic missiles, and mortars, groups like these are also increasingly able to deploy long-range suicide drones and cruise missiles. Hamas, while less advanced, also has suicide and those capable of dropping bomblets, as well as an increasingly capable artillery rocket arsenal. Countering all of this demands a diverse cocktail of solutions.

Outside of these militant groups, there is the specter of a possible attack launched from Iran, Israel’s major regional opponent. Tehran has been busily developing and proliferating unmanned aircraft, rocket, and missile technology to its proxies throughout the Middle East, as well as assembling a vast arsenal of its own, with Israel very much in its sights. Iran’s stable of increasingly advanced ballistic missiles, some of which are proven to be quite accurate, is arguably most concerning. Iran’s cruise missiles and long-range drones, which can be launched from places other than Iran where the IRGC and its proxies operate, are also extremely troubling.

Then there are still parts of the Arab world that Israel has to prepared to confront even though relations have become much better in recent years. But the specters of the past still loom large, and these countries have arsenals that are far more advanced than even a decade ago, eroding Israel’s qualitative superiority in the region.

The following primer first details the major elements of Israel’s ground-based air defense system, starting at the lower tier (in terms of altitude) and working its way up to anti-ballistic missile systems, before looking at the manned aircraft — fighters and helicopters — and warships that also form part of this overall air defensive package.

MANPADS

Little is known in the public domain about the IDF’s stockpile of man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS), although it is known to possess the widely used U.S.-made FIM-92 Stinger. While typically issued to troops for local air defense on the battlefield, the Stinger is nonetheless also useful for the point defense of critical infrastructure and can certainly be employed in this capacity by Israel. Although, Iron Dome and Israel’s advanced IADS overall would drastically reduce the need for these weapons in that role.

As we have discussed in the past, the Stinger is a short-range weapon optimized for low-level threats, although it does offer a significant engagement envelope, especially compared with previous-generation shoulder-launched missiles. While the Stinger is still optimized for targeting lower and slower-flying threats, like helicopters, it can also engage various types of higher-flying and faster-moving fixed-wing aircraft, should they get close enough. Typically, the MANPADS envelope is below around 15,000 feet, which means these kinds of weapons can also have an important role in defending against both cruise missiles and low-flying drones, something the ongoing war in Ukraine has repeatedly demonstrated. Stinger was specifically upgraded in recent years to counter small unmanned systems, as well.

Machbet

The Stinger is also integrated into the IDF’s Machbet short-range air defense system (SHORADS), which is a combined gun/missile system on a self-propelled tracked chassis, based on the M113 armored personnel carrier.

The Machbet (Hebrew for racket) is primarily intended to accompany troops on the move, specifically mechanized forces, and defend them from air attack.

The vehicle is based on the M163 Vulcan Air Defense System (VADS), specifically the Product-Improved VADS (PIVADS) introduced in the mid-1980s.

The Machbet was produced in the mid-1990s via an upgrade of existing IDF PIVADS, adding four FIM-92 Stinger missiles (plus reloads) in addition to the M168 Vulcan 20mm rotary cannon. The Machbet also added the ability to interface with the EL/M-2106 ATAR (Advanced Tactical Acquisition Radar) for surveillance, and the vehicle was fitted with an improved electro-optical sight system, including a forward-looking infrared sensor. This not only helps to detect and engage targets, but to rapidly identify them visually before doing so.

The current operational status of the Machbet is unclear, although with the IDF continuing to operate large numbers of M113-series vehicles, it’s unlikely that it will be disposed of entirely any time soon. In particular, the growing threat posed by suicide drones, as well as cruise missiles, arguably makes the Machbet more useful than ever, despite the overall age of the system.

Iron Dome

Already something of a signature weapon in the IDF armory, due to its performance in past conflicts, the Iron Dome system was developed specifically to counter small and fast-flying targets — typically the rockets, artillery shells, and mortar rounds that pose a threat to populated areas of Israel. However, aided by updates to the system, Iron Dome is also capable of intercepting cruise missiles, drones, and more.

The IDF first declared Iron Dome, which it had developed with significant assistance from the United States, operational in March 2011.

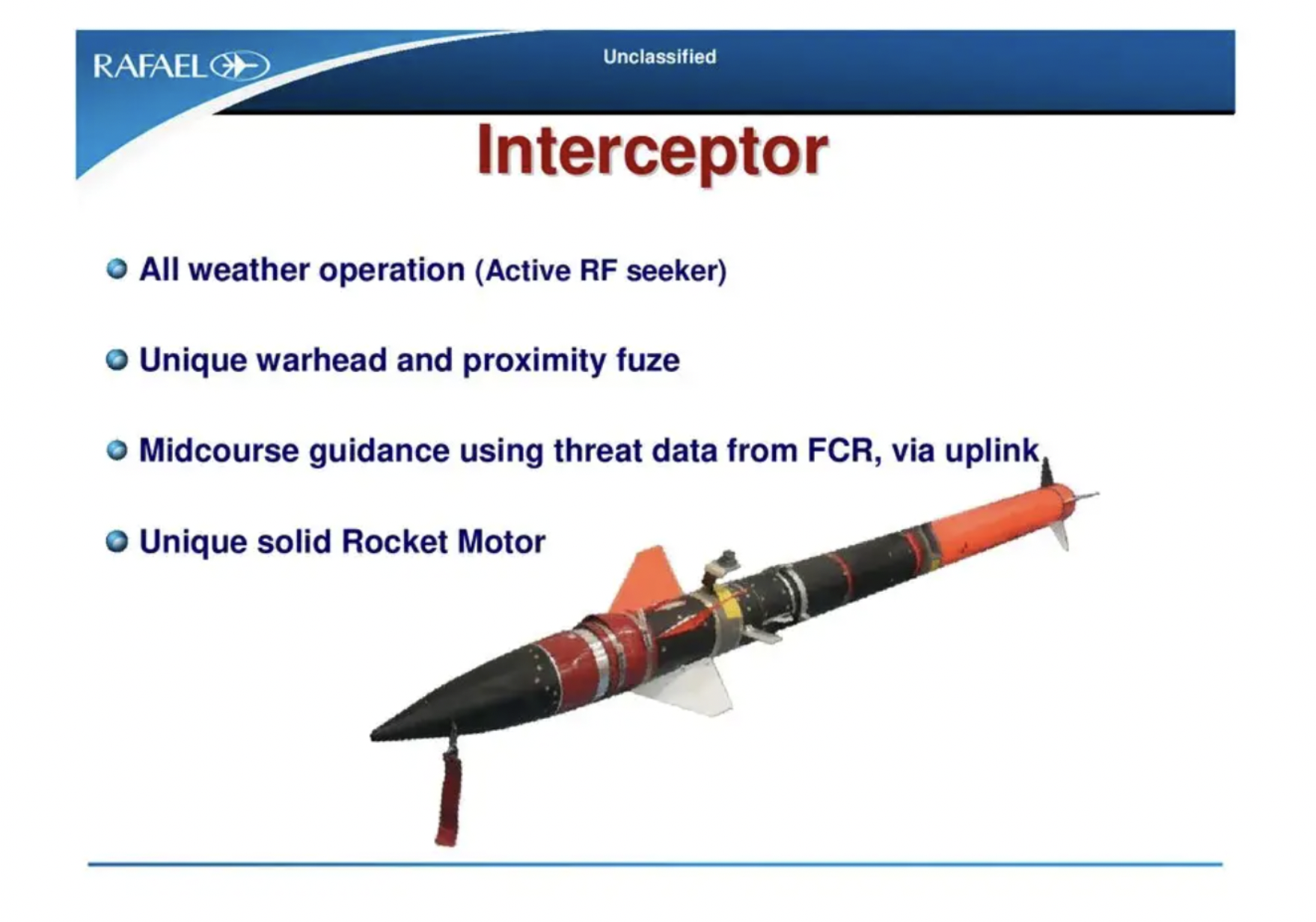

The Tamir missile used in the Iron Dome is fitted with a very sensitive active radar seeker, onboard autopilot, and a command datalink system to chase down an incoming rocket and then get to within extremely close range of it.

The missile’s warhead is designed to detonate with perfect timing, thanks to a 360-degree staring laser system, located in a collar arrangement on the forward body of the missile, behind the seeker. This proximity fuse system detects the targeted object as it begins to pass abeam the missile and triggers the onboard warhead. As it detonates, the high-explosive warhead erupts outward in a ring of shrapnel in a wedge-shaped pattern around the missile.

In fact, the missile is so agile and accurate that it will often actually slam into the incoming target, although it’s certainly not designed as a true hit-to-kill weapon.

Overall, the Tamir uses a high degree of miniaturization yet is hardened enough to withstand the extreme G forces sustained by the super-maneuverable interceptor.

A single Tamir costs somewhere between $40,000 and $100,000, depending on the sources consulted. Usually, two missiles are launched at each target to increase the probability of kill. This could change during massive barrages and as the number of interceptors in IDF stocks dwindles during a prolonged conflict. The missiles are intended to self-destruct if they do not engage a target. The heavily automated Iron Dome system also prioritizes projectiles that appear to be on a trajectory to hit population centers.

Israel currently has 10 Iron Dome batteries, although the number of launchers can vary, and they are seen as highly prized assets. Back in 2020, the Israeli Ministry of Defense claimed that Iron Dome had successfully intercepted approximately 85 percent of all targets it had faced throughout its operational history.

The Iron Dome is frequently the subject of media attention due to the dramatic light show that can result from it being used at night. It’s not uncommon for a salvo of Tamirs to stream out of Iron Dome batteries during a large barrage, or even by mistake.

In the current conflict, at least some videos showing Iron Dome in action have been misidentified as Iron Beam, a different system which we will discuss next.

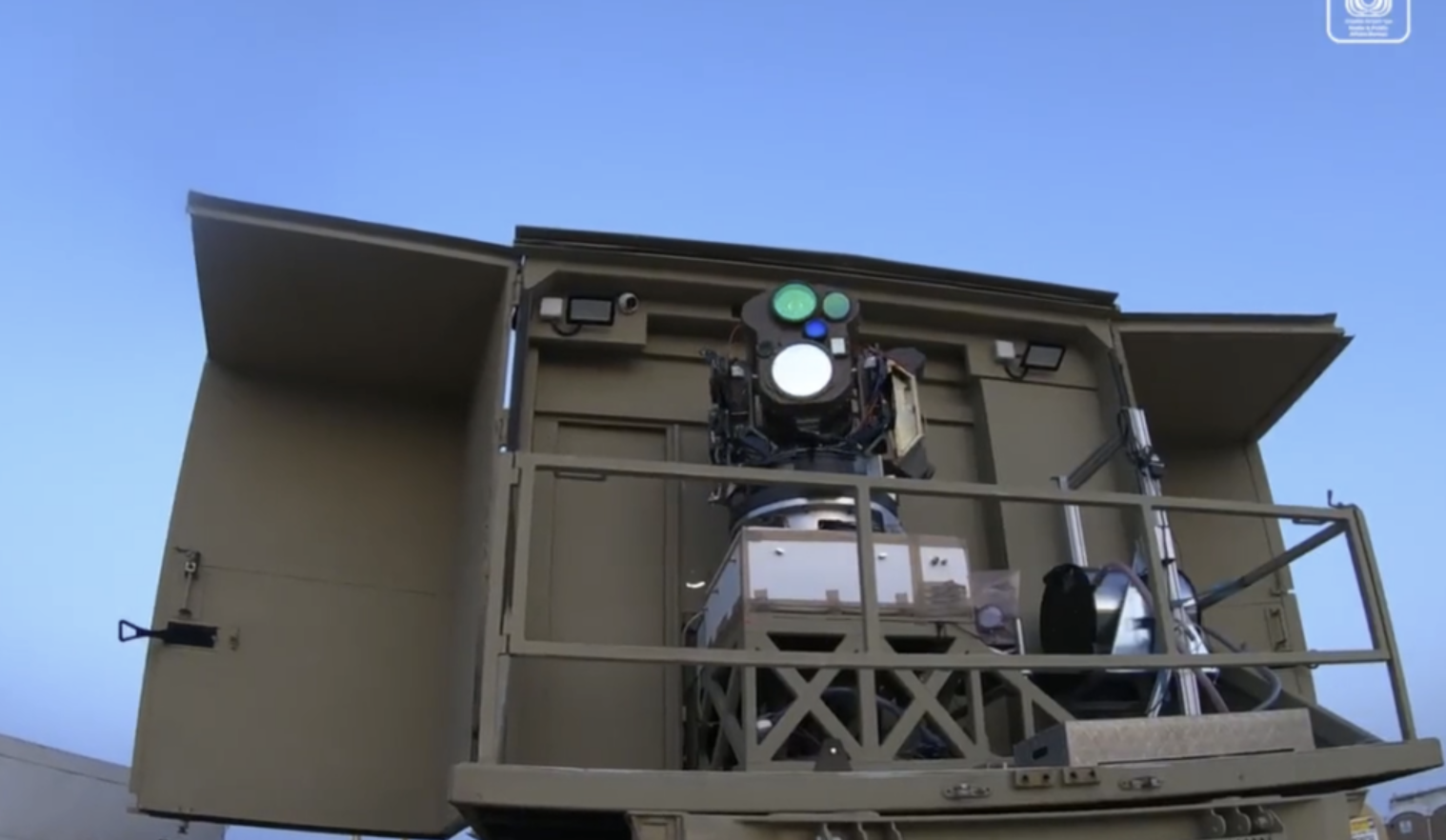

Iron Beam

A laser air defense system, Iron Beam is a trailer-mounted solution that uses a directed-energy weapon to destroy targets including rockets, mortars, and drones. Relatively new, not a great deal is known about Iron Beam’s technical specifications, although past reports described the system as firing “an electric 100-150 kW solid-state laser that will be capable of intercepting rockets and missiles.”

Last year, IDF Brig. Gen. Yaniv Rotem said that the Iron Beam had been tested at “challenging” ranges and timings,” according to the Times of Israel. “The use of a laser is a ‘game changer’ and the technology is simple to operate and proves to be economically viable,” he added.

The test referred to included the “interception of shrapnel, rockets, anti-tank missiles, and unmanned aerial vehicles, in a variety of complex scenarios,” according to the Israeli Ministry of Defense. “Israel is one of the first countries in the world to succeed in developing powerful laser technology in operational standards and demonstrate interception in an operational scenario.”

While developing a practical air defense laser has long been a challenge for many different countries, the benefits such a system offers to Israel are clear.

“This is the world’s first energy-based weapons system that uses a laser to shoot down incoming UAVs, rockets, and mortars at a cost of $3.50 per shot,” Israel’s then Prime Minister Naftali Bennett said in a tweet in April 2022. “It may sound like science fiction, but it’s real.”

While Iron Dome has proven highly effective, it burns through a lot of Tamir missile interceptors, at great expense. At the same time, the threat of a very large barrage-type attack by one or more of Israel’s adversaries could risk running out of Tamir stocks altogether, at least in the short term. Iron Beam doesn’t have that problem, of course.

The need for an air defense system in this class has seen Israel accelerate plans to deploy Iron Beam, which was originally expected to go online in 2024. According to the Times of Israel, the IDF pushed to move the timeline up out of concern that it could run out of interceptor missiles for the Iron Dome and other systems.

At this stage, Iron Beam is still very new, and its exact operational status is unclear. Laser weapons have limitations, including their range being curtailed by atmospheric conditions and their magazine depth being limited to how many successive shots they can fire before thermal loads require the system to cool down. Ultimately, however, Iron Beam will augment rather than replace kinetic systems like the Iron Dome.

David’s Sling

The mid-tier in the IDF’s air defense network is covered by David’s Sling, which, according to the IDF, achieved its first operational interception against a rocket launched from the Gaza Strip, earlier this year. David’s Sling first became operational with the IDF in 2017.

As well as larger artillery rockets, David’s Sling is intended to defeat short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs), aircraft, drones, and cruise missiles.

Each David’s Sling system includes a vertical launcher containing up to 12 Stunner interceptor missiles, each of which is reported to cost around $1 million.

In contrast to the Iron Dome’s Tamir missile, the Stunner missile fired by David’s Sling only uses a hit-to-kill concept — it relies on the interceptor slamming into the target to destroy it.

The Stunner missile features an unusual ‘dolphin-shaped’ nose profile that houses a dual-mode seeker, which combines imaging infrared and active radar seekers. Using a dual-mode seeker system means that the missile is much more resistant to hostile jamming or decoys as well as making it better suited to tackling a wider range of targets, with different signatures and flight profiles, ranging from SRBMs to stealthy cruise missiles.

The primary source of targeting data for David’s Sling is the Elta EL/M-2084 3D active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar and the missile can also receive targeting data from third-party sensors, fed by an onboard datalink.

In ground-launched form, the Stunner missile has a two-stage propulsion system. This provides higher levels of energy and maneuverability to ensure that the hit-to-kill second stage finds its target, even if that is maneuvering at speed. Not having to pack that second stage with an explosive warhead and fuze also means that overall weight is reduced, again helping with speed and agility, as well as overall range. The range of the missile is reportedly between 150 and nearly 200 miles, although most engagements are likely to take place at much shorter distances.

Patriot PAC-2

The U.S.-made Patriot air defense system falls somewhere between the upper-tier Arrow, which specializes in ballistic missile defense, and David’s Sling, which occupies the mid-tier.

Specifically, the IDF operates the PAC-2 GEM-T version of the Patriot, with eight batteries reportedly deployed. These systems have also been subjected to local upgrades and they are known by the local Hebrew name Yahalom, meaning diamond.

The GEM-T designation refers to Guidance Enhanced Missile — Tactical. As we have explained in the past, the GEM subvariants are produced by upgrading older MIM-104C and D missiles to the E configuration. Converted MIM-104Ds were given additional upgrades to improve performance against tactical ballistic missiles, hence the GEM-T designation. As for the MIM-104E configuration, this features a completely new front section with upgrades that give both sub-types improved accuracy and overall performance. These interceptors feature various reliability updates, as well.

Raytheon still produces the GEM-T subvariant today and the design has received further enhancements over the years. This means that Israeli stocks of these missiles can be replenished from the U.S. production line.

For the IDF in particular, the PAC-2’s anti-ballistic missile capability is extremely relevant, although the system is highly versatile and can engage a wide variety of targets. As well as fast-moving ballistic missiles, for example, the PAC-2 GEM series features an improved seeker designed to help better engage smaller targets or ones otherwise with smaller radar cross-sections. Fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters, cruise missiles, and drones are all on the potential feeding list for Israel’s Patriot batteries, but the anti-ballistic missile capability has long been the highlight of the system.

Arrow

The Arrow 3, developed jointly by Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) and Boeing, fills the uppermost tier of the IDF’s air defense shield and is primarily intended to defeat ballistic missile threats, especially those flying at very high altitudes and at extremely high speeds. The Arrow 3 entered operational service in January 2017.

The Arrow 3’s interceptor component carries a kinetic kill vehicle outside of the Earth’s atmosphere (exo-atmospheric), where it physically slams into the target, destroying it in its mid-course flight phase. This is different than the capabilities of Patriot and, to a lesser extent, David’s Sling, both of which counter ballistic threats during their terminal stage of flight — when the projectile is careening down on its target during the end portion of its flight.

Exo-atmospheric interceptors are especially well suited to tackling longer-range ballistic missiles, including those that may be carrying nuclear warheads. Destroying missiles like this outside of the atmosphere provides an additional degree of safety. According to reports in the Israeli media, the Arrow 3 can intercept targets at a range of around 1,490 miles.

The Arrow 3’s predecessor, the Arrow 2, was the world’s first anti-ballistic missile system to be designed as such from the ground up. Primarily designed to defeat short- and medium-range ballistic missiles, it also uses an exo-atmospheric interceptor. It was first deployed in 2000. According to local media reports, the Arrow 2 was first used operationally in March 2017 when it destroyed a Syrian surface-to-air missile.

Unlike the Arrow 3, the Arrow 2 missile’s finned kill vehicle is fitted with a high-explosive/fragmentation warhead. The missile uses a dual-mode seeker, with imaging infrared and active radar seekers.

Reportedly, the Arrow 2 can intercept targets at a maximum range of 62 miles and at altitudes of up to 31 miles, meaning that it’s likely retained to tackle lower-altitude targets than the long-range Arrow 3. So, as you can see, Israel has created a densely layered anti-ballistic missile capability, with Arrow 3 being by far the most capable of those layers.

Fighters and helicopters

A critical part of the IDF’s air defense capabilities are the manned fighters and attack helicopters operated by the Israeli Air Force, as well as the surveillance and command-and-control assets operated by the same service.

While Israeli fighters and attack helicopters are often tasked with offensive missions, aircraft, in general, offer a much more flexible response to certain kinds of airborne threats than ground-based missile systems.

The Israeli Air Force’s fleet of F-15, F-16, and F-35 fighters are all able to intercept drones — and also cruise missiles, at least in some scenarios. This is in addition to countering manned fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft and providing general air sovereignty for Israel.

Even the ‘silver bullet’ F-35I stealth jet fleet has been used to intercept unmanned aerial vehicles and shoot them down. In their first aerial engagements, Israeli F-35s brought down at least two Iranian drones that the Israeli Air Force says were heading toward Israeli territory in 2021. The F-35, with its sensor-fused avionics, is an outstanding platform for detecting hard small targets and visually identifying them before engagement.

Israeli AH-64 attack helicopters have also been employed for counter-drone operations, with the rotorcraft’s flexibility in terms of deployment and its low-speed capability making it highly suitable for targeting certain categories of drones. Hellfire missiles can be used for a counter-air application against these targets.

An IDF video purportedly showing an Israeli AH-64 intercepting an Iranian UAV that crossed into Israeli territory:

Nachshon and Oran

As well as these ‘shooter’ assets, the Israeli Air Force also operates some key intelligence-gathering assets that provide a critical contribution to the overall air defense picture. Overall, the IDF can call upon many kinds of sensor systems, drawing upon a vast network, on the ground, in the air, at sea, in space, and in cyberspace. However, surveillance aircraft with a look-down capability are a huge force multiplier, and worth looking at in their own right.

In recent years, the Israeli Air Force has operated two different aerial surveillance platforms based on the Gulfstream 500/550 executive jet airframes. These are the three Shavit (signals intelligence) and two Eitam (airborne early warning and control) aircraft. Collectively, these aircraft are known as Nachshon. The latest addition to the family is the Nachshon Oron, which combines many of the functions of the Shavit and Eitam in a single Gulfstream G550 airframe.

The Oron, which you can read about in detail here, is understood to be equipped with a conformal electronically scanned array (AESA) radar system, as found in the Eitam, with its antennas around the fuselage providing 360-degree coverage. These high-flying jets, with their long radar horizon and ‘look-down’ capability, are especially important for detecting small targets like stealthy cruise missiles and drones at long ranges, and particularly those that are are flying at low-level.

The Oron is also fitted with signals intelligence (SIGINT) sensors and is assumed to have a ground-scanning radar capability with ground moving target indicator (GMTI) and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) modes. The SIGINT package gives the Oron (as well as the earlier Shavit) the ability to detect emissions from threats, including from hostile radars, aircraft, and drones. Once these have been uncovered in this way, other sensors can also be used to track them and target them if required.

Using all these advanced sensors, these aircraft are able to survey large swaths of land, air, and sea, including detecting, tracking, and passing on the coordinates of various airborne threats. At the same time, the Oron and other members of the Nachshon fleet work closely with ground stations, allowing much of the processing and interpretation work to be done remotely, but also in real or near-real time. Furthermore, using GMTI and SAR functions, these aircraft would also be able to detect missiles and rockets, for example, before they are even launched. Flight-tracking data reveals these aircraft have been very active since the start of the current conflict.

Sa’ar corvettes

A lesser-known element of Israel’s air defense umbrella is provided by the Israeli Navy’s small but capable surface fleet. In particular, the Sa’ar 5 class of three missile corvettes can serve as radar pickets, feeding targeting data to the Iron Dome batteries, for example. The Sa’ar 5 is well equipped for the purpose, with its EL/M-2248 MF-STAR multifunction AESA radar being able to automatically track and engage a full spectrum of aerial threats, from aircraft to sea-skimming missiles, at ranges up to 124 miles.

While the Iron Dome is typically land-based, in recent years, the Israeli Navy has also started to put its corvettes to sea with these missile batteries onboard, in addition to the warships’ own Barak surface-to-air missiles. The Barak, too, can have an important role to play defending objectives on land, as well as at sea. Starting out as a point-defense weapon, the Barak has been fielded in successively improved iterations, with the latest Barak 8 having a range of 43 miles and the ability to engage ballistic missiles as well as aircraft, cruise missiles, and drones.

Back in 2021, photo evidence emerged of the Sa’ar 5 class corvette Lahav armed with two Iron Dome launchers, located on the ship’s helicopter flight deck, apparently for the first time. This came amid reports that Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen possessed Iranian-supplied suicide drones and cruise missiles capable of reaching targets within Israel.

As we reported at the time, loading a Sa’ar 5 class corvette with Iron Dome in this way could provide a useful anti-air screen to defend against drones and cruise missiles launched from land or a surface vessel in the Red Sea, for example, swatting them down before they approach Israeli borders. A potential threat of a drone or missile launch from the Mediterranean could also be tackled by a vessel outfitted in the same way. It’s also noteworthy that Hezbollah has, in the past, sent drones over Israel by way of a route along the shore of Lebanon and into Israel.

The Israeli Navy is currently expanding its air defense capabilities with the introduction of the Sa’ar 6 class of four missile corvettes. As part of their standard weapons configuration, these boats will be fitted with C-Dome — the naval derivative of Iron Dome. C-Dome employs the interceptor missiles, vertical launchers, and other components from the land-based battle management center, together with the ship’s own surveillance radar.

As well as relying on all these overlapping and complementary capabilities to defeat the various threats Israel faces from the air, the IDF would aim to target hostile systems ‘left of launch’ — before the enemy has a chance to actually send them toward Israel.

Increasingly, the limitations of ballistic missile defense, in particular, are driving militaries to look at their ‘left of launch’ capabilities. Here, the IDF can call upon its own long-range strike forces, including aircraft and missiles, but the complex nature of the threat means that it would also have to call upon non-kinetic methods, including electronic warfare and cyber warfare. Against the most basic kinds of threats, such as militant mortar and rocket teams, the best way to ensure ‘left of launch’ might be timely intelligence and the ability to launch a pinpoint drone or attack helicopter strike.

In the realm of higher-end threats, Israel’s highly advanced cyber capabilities can work to disrupt an enemy’s ability to launch a weapon in the first place. The IDF’s deep bag of electronic warfare tricks can also be used to ‘soft kill’ some enemy systems before they can deliver their deadly payloads. The intelligence aspect of this is also critical — knowing when a threat will emerge or could emerge is critical to making sure sensors and weapons are in position to counter those threats if need be.

Finally, all the data from sensors in the air, at sea, in space, and on the ground that make up the ‘air picture’ in the region has to be processed and analyzed very quickly. Underpinning this is AI-driven software and advanced computing and communications hardware that pulls all the information together so that air defenders can make critical calls very quickly.

All of this can be considered under the auspices of air defense in the modern era of warfare. It also goes some way to explain the complexity of the threat that Israel faces when it comes to defending itself from attack from the air. Not only do the types of threat range all the way from simple man-portable rockets and mortar bombs all the way up to long-range ballistic missiles, but these weapons might be launched from a range of different vectors, potentially simultaneously, and also in huge numbers. With this in mind, it’s easier to see exactly why Israel has invested in such a powerful and deeply layered integrated air defense system.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com