Collins Aerospace has put forward a vision for what a high-end air combat engagement between the U.S. and Chinese armed forces, with the American side employing crewed fighters and Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) drone wingmen, could look like in the future.

A division of Raytheon (now formally known as RTX), Collins released the glitzy computer-generated video seen below last week primarily to showcase its work on autonomous capabilities that could support the U.S. Air Force’s CCA program, as well as the U.S. Navy’s separate, but closely related effort of the same name.

The video opens with U.S. forces forming for the mission at hand. CCAs are showing taking off from a remote airstrip and an aircraft carrier. This highlights the potential for the drones to be launched from disparate operating locations and not necessarily ones tied to the basing of their crewed companions. The War Zone has noted in the past how drones with limited dependence on traditional runways, or even complete runaway independence, could be extremely valuable in future distributed operations.

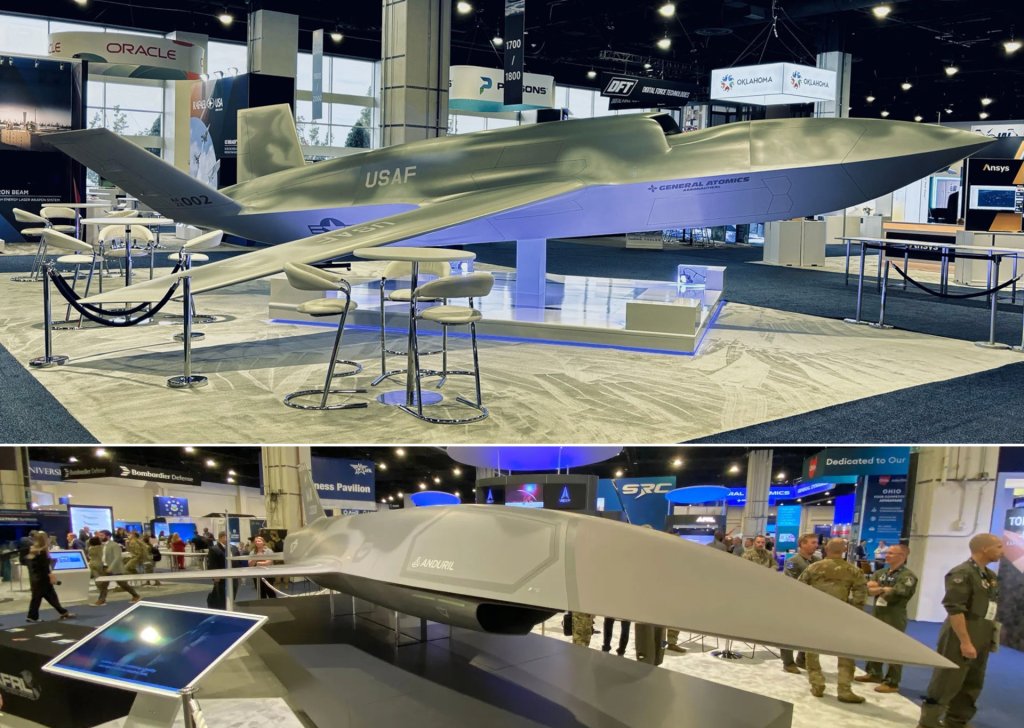

Two different kinds of notional CCAs are depicted. One that has some very general similarities to Anduril’s Fury. The other looks very much in line with Kratos’ XQ-58 Valkyrie. A CCA design that General Atomics is currently working on also has a broadly similar overall configuration with a top-mounted intake and v-tail.

Fury and General Atomics’ CCA design are currently under development as part of the first phase of the Air Force’s CCA program. The Air Force, as well as the U.S. Marine Corps, have also been flying XQ-58s to support work on autonomous capabilities, as well as other research and development and test and evaluation efforts.

Collins’ video shows two-seat F-15E Strike Eagle derivatives, F/A-18F Super Hornets, and F-35 Joint Strike Fighters as the crewed controllers for the CCAs. Both the F-15s and F/A-18Fs are notably shown carrying podded infrared search and track (IRST) systems, as well as full air-to-air combat load-outs including AIM-120 Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missiles (AMRAAM) and AIM-9X Sidewinder missiles.

The F-15s depicted in the video are some of a hybrid of real-world variants. The jets are shown with additional outboard underwing pylons currently only found in U.S. Air Force service on the F-15EX Eagle II, but lack other key features on that version. The aircraft also have “MO” tail codes indicating jets based at Mountain Home Air Force Base in Idaho, where F-15E Strike Eagles are based. There are no current plans to replace the F-15Es in Idaho with EXs.

The War Zone has repeatedly highlighted how two-seat tactical jets like the F-15EX would be particularly well suited to serving as airborne drone controllers since the individual in the back seat could handle that mission while the pilot focuses on actual flying.

Back-seaters in F-15s and F/A-18Fs are seen issuing instructions to their pilotless wingmen via touchscreen interfaces on tablet-like devices. The F-35 pilots are depicted using the same user interface via the wide-area display in their jets’ cockpits. The user interface that is shown provides the ability to select multiple drones at once and to direct them to perform pre-set mission profiles – including transit, defensive counter air (DCA), and combat air patrol (CAP) – at least semi-autonomously.

In the video, the drones are ordered first to transit to a mission area before being switched over to the DCA mode. Doing this causes the CCAs to turn on their sensors and begin scanning, at which point various threats – a mix of Flanker variants and Chinese J-20 stealth fighters – are detected.

One of the most commonly cited benefits of groups of drones tethered to piloted fighters in air-to-air combat is the ability of the uncrewed component to extend the sensor reach of the entire force without necessarily increasing the risks to the crewed component. For instance, CCAs could employ active sensors and pass the information they gather along to piloted fighters operating their sensor suites in a passive mode making them harder to detect. Crewed combat jets could also potentially engage enemies based on that targeting data forwarded from drone wingmen. With additional networking connectivity, the data collected by the complete crewed-uncrewed team could be pushed to other nodes, as well.

Text narration in the Collins’ video highlights how a human-machine team could “collaborative search the battlespace, detecting threats building shared understanding, triangulating to generate target tracks.”

It’s also worth noting here that one of the key benefits of the IRST systems that the F-15s and F/A-18Fs are depicted carrying in the Collins’ video is that they function passively, which also does not alert opponents to the fact that they are being tracked. IRSTs, which be paired with other sensors to provide additional capabilities, are also immune to radiofrequency electronic warfare jamming. You can read more about the value of IRSTs, which are seeing a renaissance in the U.S. military, here.

The video from Collins subsequently shows U.S. fighters and CCAs engaging and shooting down a number of Chinese jets. Interestingly, the footage does not appear to depict any direct authorization being given to the drones before they fire their missiles. U.S. military officials have stressed repeatedly that, at least for the foreseeable future, a human operator somewhere ‘on-the-loop’ will always be responsible for authorizing uncrewed platforms in the air or anywhere else to employ lethal force.

After combat concludes, the video shows different groups of CCAs being directed to maintain CAPs or return to base (RTB). As seen below, the user interface at this point in the computer-generated footage also shows what looks to be options for handing off control of the drones from the fighters to other aircraft, as well as ships and forces on the ground, and even nodes in space. The Air Force and Navy are already known to be working on ways to be able to seamlessly exchange control of CCAs in future operations. There has been talk of expanding portions of that architecture out to other branches of the U.S. military, as well as to allies and partners.

The scenario outlined in the Collins’ video is, of course, notional and, in many ways, truncated. A high-end aerial combat mission like this would likely occur across a much broader area with actual engagements occurring at beyond visual range.

Notably absent entirely in the footage are hostile uncrewed combat air vehicles (UCAV) and other drones, which the Chinese aviation sector is very actively developing. When it comes to stealthy highly-autonomous flying wing UCAV, in particular, this is a space the United States has all but completely ceded to China, at least publicly.

In the video, neither side is shown leveraging their still-growing arrays of offboard air and other assets that would be involved in any operation of this kind, either. U.S. military officials have routinely cited China’s growing airborne early warning and control and aerial electronic warfare capabilities as being major expected factors in any future air-to-air engagement between the two countries.

What Collins’ has put out still presents an interesting outlook for what highly autonomous crewed-uncrewed teaming might look like in future high-end aerial combat. It also highlights questions about concepts of operations when it comes to executing these kinds of teamed air-to-air engagements, as well as basing and sustaining CCAs, that the Air Force, as well as the Navy, are still very much working to answer.

The Air Force “has talked about potentially having as many as 1,000 of these CCAs to use in a contingency,” Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach, head of Air Combat Command, said at a talk that the Air & Space Forces Association’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies hosted earlier this year. “And I think that’s a noble goal, and one that would create a lot of dilemmas as people think about getting into a fight with us and having to contend with that many, plus all of our manned platforms.”

At the same time, “you probably don’t need to fly that [CCA] aircraft every day,” Wilsbach continued. “And in fact, what we think is that we’ll have these aircraft available to fly, but they won’t fly that often. And the benefit of that is you don’t need the maintenance. You don’t need the long-term sustainment, and so you get a lot more airframes for a given amount of money.”

Wilsbach added at that time that the drones would likely be kept essentially in “flyable storage” and “in a hangar and they’ll be ready to fly” most of the time, only being brought out when necessary. You can read more about the benefits of an operational concept like this in this past War Zone feature.

Exactly how CCAs will be controlled and what levels of autonomy may truly be available in the near term to support all of this still very much remains to be seen, as well.

“There’s a lot of opinions amongst the Air Force about the right way to go [about controlling drones from other aircraft],” John Clark, Lockheed Martin Vice President and General Manager of Advanced Development Programs (ADP), better known as Skunk Works, told The War Zone and others at this year’s Air & Space Forces Association’s (AFA) Air, Space & Cyber Conference earlier this week. “The universal thought, though, is that this [a tablet or other touch-based interface] may be the fastest way to begin experimentation. It may not be the end state.”

“We’re working through a spectrum of options that are the minimum invasive opportunities, as well as something that’s more organically equipped, where there’s not even a tablet,” Clark added.

Testing to date has exposed potential issues around using tablets and other touch interface systems.

“We started with [the Air Force’s] Air Combat Command with tablets… There was this idea that they wanted to have this discreet control,” Michael Atwood, Vice President of Advanced Programs for General Atomics, said during an appearance on The Merge podcast earlier this year. “I got to fly in one of these jets with a tablet. And it was really hard to fly the airplane, let alone the weapon system of my primary airplane, and spatially and temporally think about this other thing.”

At that time, Atwood advocated for ceding greater control to drones under human supervision.

“We know two things about autonomy,” Andrew Hunter, Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology & Logistics, told The War Zone and other outlets at a media roundtable on the sidelines of this week’s AFA conference. “One is laws of war require us to have, you know, human engagement in key decisions involving employment of weapons and other key decisions. So we have to have that. We have to have that human engagement, the ability to do that. The second is [that] we know that our ability to create systems that can operate autonomously and do missions well is something that is still maturing.”

“So, in other words, there are things that we know that we already know how to do well with autonomy, and there’s things that we know we do not know how to do well with autonomy,” Hunter continued. “So we’re going to stick to the things we know we can do well, and then have humans do the other things, and, over time, that mix is going to change… it’s not going to be static.”

With the Air Force pushing hard to begin fielding its first operational CCAs by the end of the decade, it should become increasingly clear in the coming years how well Collins’ vision does or doesn’t align with reality.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com