An inside look at the life of a Ukrainian Su-27 Flanker fighter pilot in the country’s war with Russia is the focus of a recently released video from the Ukrainian Air Force. The interview with the Su-27 pilot, callsign “Viking,” is a rare opportunity to hear about some of the challenges — and successes — of the Ukrainian Air Force’s fighter fleet, which, despite the recent introduction of F-16s, is still dominated by the Soviet-era Su-27 and MiG-29 Fulcrum.

Viking starts the interview with some reflections on the very first days of fighting after Russia launched its full-scale invasion on Feb. 24, 2022. His experiences sound very similar to those of the late MiG-29 pilot “Juice,” who was interviewed several times by TWZ before his death in a training accident in August 2023. The loss of Juice has also meant opportunities for these kinds of interviews are now much reduced.

Viking was not at his normal base in the Zhytomyr region when the war started, he was in Kyiv. His race to Zhytomyr was frustrated by a lack of rail services out of the capital and ended with a walk between 25-30 miles to get to the air base, still in civilian clothes. Once there, he was very quickly in the thick of action, and from Feb. 25 on he flew air defense missions that he described as “deterrence,” first flown in daylight and later at night, over the Kyiv region.

“We held them back,” Viking explained. “If their aircraft had come here and worked freely, everything would have been completely different.”

Viking and his fellow 39th Tactical Aviation Brigade (39 BrTA) pilots faced a significant disadvantage in terms of radars and missiles compared to the Russians. While Ukrainian fighters could occasionally track enemy aircraft, getting within missile-launch range was rarely possible.

The Ukrainian Air Force began the war with around 32 Su-27s operational within two brigades, the 39 brTA at Ozerne in the Zhytomyr region of northwestern Ukraine and the 831 brTA at Myrhorod in the Poltava region of central Ukraine. At least 15 Ukrainian Flankers have been visually confirmed as destroyed but, in the meantime, additional examples have also been returned to airworthiness after overhauls. The aircraft are also regularly moved around between different operating locations, some of them austere in nature, making it harder for the Russians to target them.

www.twz.com

Like many pilots and other Ukrainians, it took time for Viking to grasp the reality of the war, with the feeling that “I’ll wake up and everything will be over” characterizing what he described as a difficult period in his life. The resilience of Ukrainian non-combatants was also plain for him to see: his girlfriend chose to stay in Zhytomyr, with their cat, rather than leave the country; his parents also stayed at home, and his mom sent a photo of a basket of Molotov cocktails with the message that she planned to use at least one on the invaders.

“They were in a fighting mood, and I was also in a fighting mood, but it was hard…” Viking reflected. “The most difficult thing was misunderstanding. [Due to] the instability of the front, there was a minimum of information.”

As an example, in these early days, Viking’s available intelligence on Russian air defenses was scrawled on a piece of map that he’d torn off, with information vital for survival being exchanged by word of mouth between pilots. The map simply showed the best route into a given area, with circles showing the approximate engagement ranges of hostile air defenses.

The primary job at this time was attempting to blunt the advance of Russian tactical aircraft flying from Belarus. “We were the only ones here, to put it bluntly. We were the first line of defense, and they were constantly trying to sneak their Su-34s and Su-35s in at night, at extremely low altitudes.”

Complicating their job was the fact that, according to Viking, the avionics and missiles of the Ukrainian Su-27s, at this time, were “two generations behind” those of the Russians. Within these parameters, “the battle was reduced to trying to get closer to [the Russians].” But even if that was possible, the Ukrainian Su-27 pilots were rarely able to get within the launch parameters of their missiles, with the Russian jets always having the opportunity to launch weapons first.

“Even though our [missile] launches had short ranges, we still tried something, we launched missiles, we held the Russians back, and we repelled these attacks every night,” Viking explains. “Almost every pilot flew two, sometimes three sorties each night.”

One particular sortie that Viking recalls involved a “very, very difficult” hour-and-a-half air battle at night, during which six missiles were launched against his Su-27: “four launches from aircraft, two launches from the ground.”

Viking’s second flight that night, March 1, 2022, involved a failure of his navigation instruments, in worsening weather, with gathering clouds and fog. He had to be guided by a ground controller to land at Starokostyantyniv Air Base in western Ukraine.

“I lost my spatial orientation,” he says. “It’s scary, you don’t understand where you are, you don’t understand where you are heading, in what attitude you are in.”

“Every new day of this war posed new challenges, all our training, all our vision, was based on rather outdated experiences and our weapons were quite outdated.” This was especially the case when going up against more modern Russian air defense systems, some of which work “at a crazy range” as well as being highly mobile, in the case of the Buk and Tor (SA-11 Gadfly and SA-15 Gauntlet) especially.

Russian air defenses made it “impossible” for the Ukrainian Air Force to drop conventional unguided ordnance, making the arrival of Western-supplied precision-guided weapons an absolutely critical factor. These new weapons allowed Ukrainian jets to operate “a little further from the front line,” thanks to the standoff range of the new weapons. Now the Su-27 began to flex from its air-to-air specialism to more offensive strike duties.

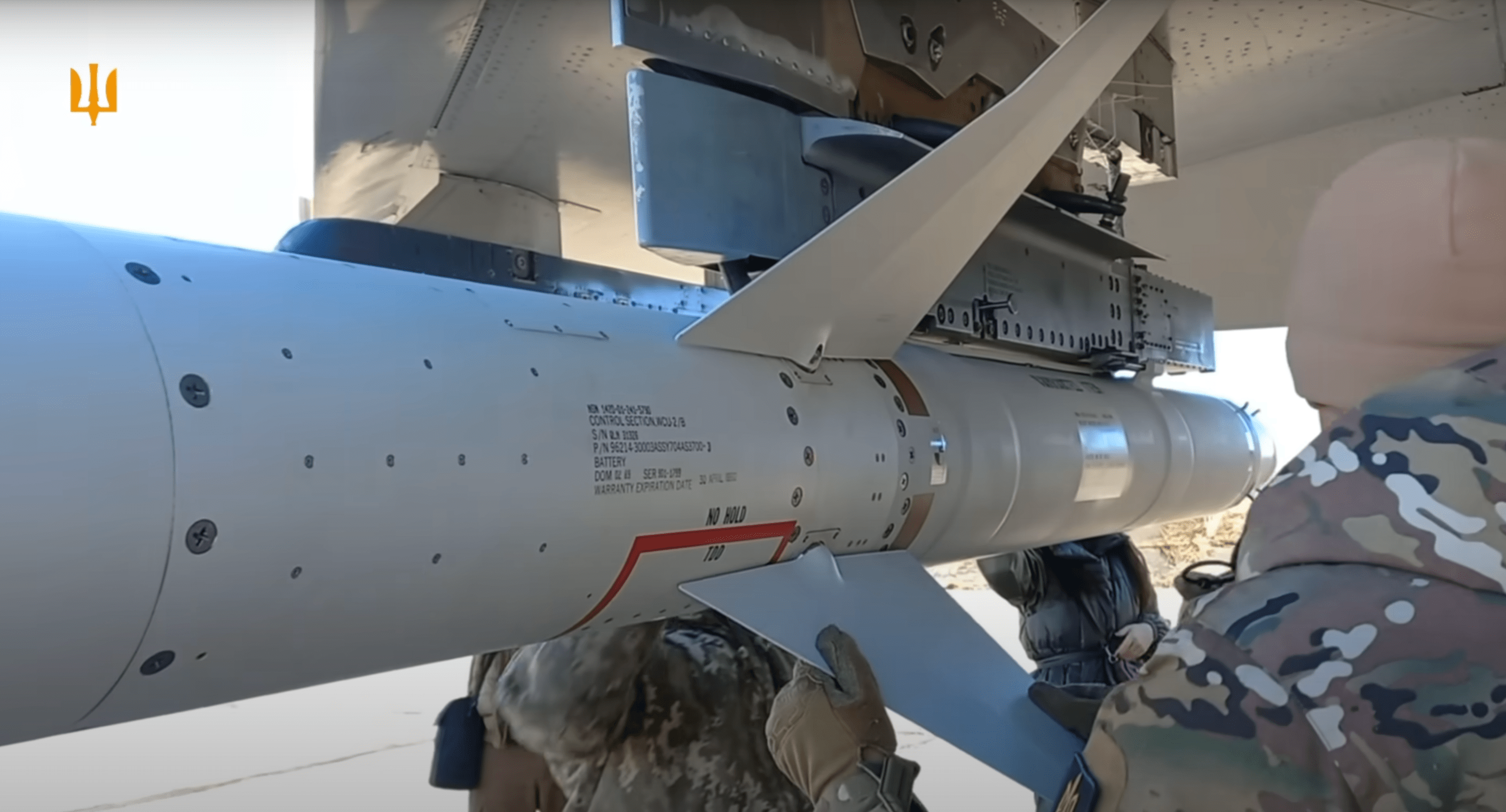

Viking’s first experience using the AGM-88 High-speed Anti-Radiation Missile, or HARM, resulted in a claimed 90% success rate against Russian ground-based defense targets, demonstrating “the incredible effectiveness” of the weapon. Other milestones included Viking’s first downed drone, a challenging target for a fast-moving relatively low-tech jet, as we have discussed before.

Viking noted that Russian media reports were highly skeptical about how U.S.-supplied weapons would be used on Ukraine’s Soviet-era aircraft, and even if this was possible. Some Russian accounts predicted that the HARMs would more likely be launched from the ground, off the back of adapted trucks, rather than from the air. The innovative approach to integrating Western weapons on Soviet-era fighters eventually involved a combination of new tactics, specially designed pylons that can pass targeting information to the missiles, as well as tablet-based cockpit interfaces.

Russian doubts “played into our hands,” Viking says. “We destroyed a lot of [air defense] complexes, damaged them, suppressed them, and forced them to retreat. This gave us space to come a little closer [to the front lines].” This, in turn, allowed Ukrainian airstrikes to reach further, bringing critical Russian military targets in Ukraine within range. “Even the main command post of the Russian Ground Forces was hit,” Viking explains. “They were, let’s say, punished for their insolence.”

Today, the HARM is mainly used as a “support weapon,” Viking says, meaning that they provide defensive escort for other Ukrainian aircraft, dealing with pop-up Russian air defense threats that might be encountered en route to other objectives.

After the HARM, Viking’s brigade received the Joint Direct Attack Munition–Extended Range (JDAM-ER) and the GBU-39/B Small Diameter Bomb (SDB).

While he considers the 500-pound JDAM-ER to be relatively efficient, even in the face of intense Russian electronic warfare countermeasures, he singles out the SDB for particular praise, confirming that a single Su-27 can carry eight of these bombs.

Not only is the range of the SDB “a little longer” than that of the JDAM-ER, but Viking considers it to be harder for Russian air defenses to deal with due to its “small reflective surface” providing a trickier radar target, combined with the fact that it can be dropped in bigger salvoes.

“Despite the fact that it’s quite small, it’s quite a powerful bomb,” Viking says of the SDB, noting that it can penetrate around six feet of reinforced concrete. The design philosophy behind the SDB is also in stark contrast to Soviet-era aerial bombs, which always prioritized size and weight — “the main thing for them is that there should be a big explosion, rather than accuracy.” However, more explosive doesn’t necessarily translate to greater destructive power, as the SDB has shown.

The difference in approach is also seen in Russian tactics. Viking says the Russians frequently use at least 10 times as many munitions in one single area of the front lines than Ukraine does across the entirety of the front lines in a month. Viking suggests that, while Ukrainian munitions might achieve an accuracy as high as 85%, Russian equivalents might only attain 15-20% on target, hence the need for more and heavier weapons to compensate.

Viking also warns again about the particular threat posed by Russia’s relatively recently developed low-cost precision-guided glide bombs — a menace that has frustrated Ukrainian air defenses since they first began to appear in early 2023.

“To treat the symptom, it’s necessary to drive away the carriers of these glide bombs, but this is a difficult task, and it requires a complex approach. Unfortunately, there is no magic wand to drive them away. It needs a complex approach, including both the aviation component and the ground component, as well as the necessary air defense radars, and air-to-air missiles that have the ability to hit, at least at medium altitudes, targets at a range of 100 kilometers [62 miles],” Viking says, referring to the need for beyond-visual-range missiles to target the aircraft launching the glide bombs.

“Without all these means, if the Russians continue to throw glide bombs, then the consequences will be terrible, they will simply squeeze us out, no matter how incredible our infantry is.”

The Russian glide bomb problem became one of the main arguments for accelerating Ukrainian F-16 deliveries, although it remains to be seen how effective these might be in pushing back the Russian jets launching glide bombs from across the border.

As the war approaches its three-year anniversary, Viking reflects that while physically tired, his morale remains as high as ever. “The war requires 100% of your effort,” he says. “Even when you go on leave for 15 days, you come back and you don’t quite understand why already everything has changed: we are working in a new way, in new areas, the enemy has come up with a countermeasure, and we have come up with some kind of countermeasure ourselves.”

Despite limited F-16 deliveries so far and continued losses to the Soviet-era fleet of tactical jets, Viking says there is no shortage of trained manpower or aircraft at this point. Instead, what the Ukrainian Air Force lacks is air-launched weapons. Only greater numbers of these, he says, will be able to achieve some kind of parity with Russian airpower capabilities.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com