Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky says that his country has conducted the first successful test of a new domestically-developed ballistic missile. Ukraine is known to have at least one short-range ballistic missile (SRBM), the Hrim-2, in some stage of development, as The War Zone previously explored in detail. Such a weapon would give Ukraine’s armed forces a highly valuable new stand-off strike option unlike any other in its inventory. It would also not be subject to any foreign restrictions on its use, as it continues to be the case with many longer-ranged weapons supplied by the United States and other Western partners.

“There has been a positive test of the first Ukrainian ballistic missile,” Zelensky said at a press conference earlier today around the Ukraine 2024 Independence forum in the country’s capital Kyiv, according to AFP. “I congratulate our defense industry on this. I can’t share any more details about this missile.”

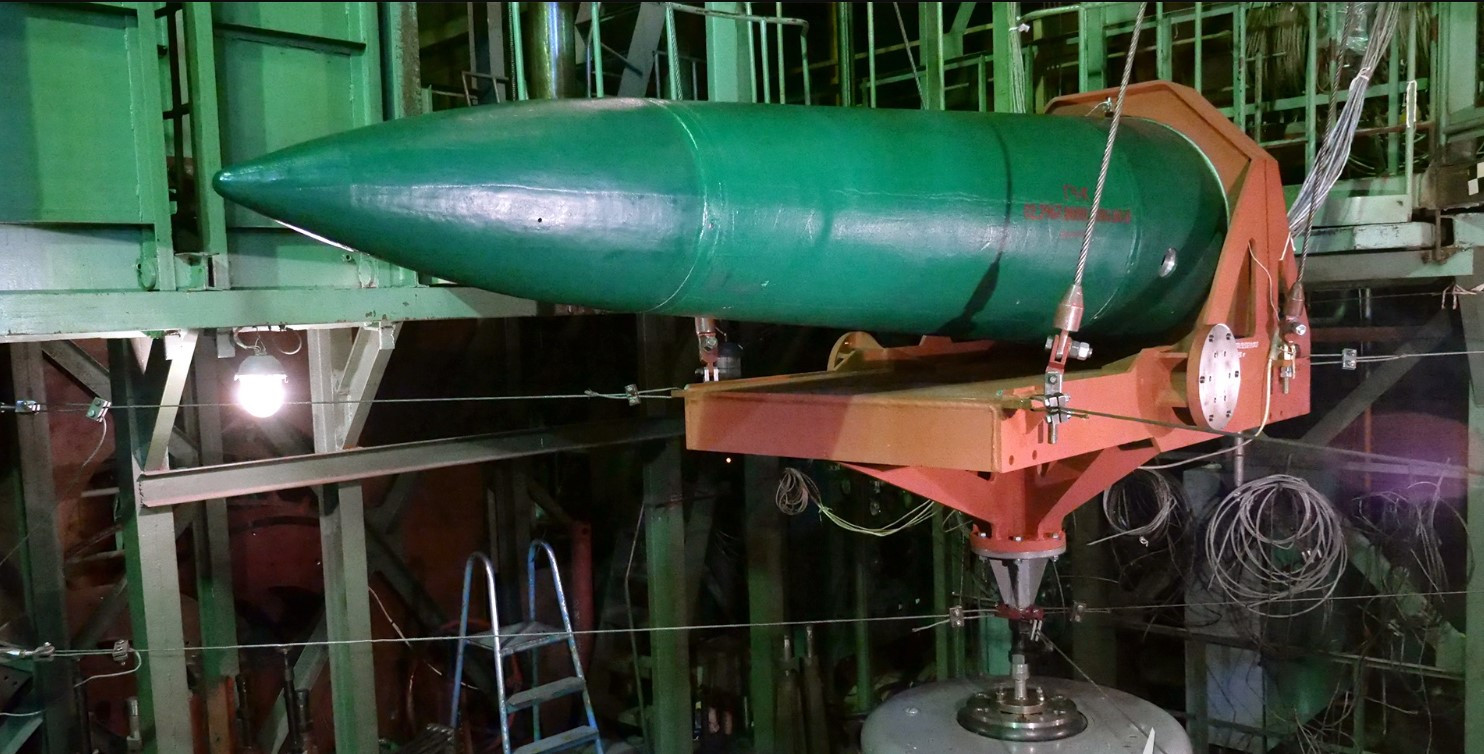

Zelensky did not name the missile, but discussions have already turned to the possibility of him referring to Hrim-2 (also written Grim-2 and which translates as Thunder-2 in English). The origins of the Hrim-2 and its immediate predecessors date back to the late 2000s and development is understood to have begun in greater earnest after Russia seized the Crimean Peninsula in 2014. A rocket motor test associated with the design occurred in 2018 and the two-round, 10-wheeled transporter-erector-launcher for the missile, or at least a mockup thereof, wearing Ukrainian Armed Forces markings appeared at a parade that same year.

The Hrim-2 and preceding related designs, as they have been shown to date, have outward appearances that are very similar to Russia’s Iskander-M. Hrim-2 could have a range of at least 174 miles (280 kilometers) and possibly up to 310 miles (500 kilometers), according to past reports.

You can read more about what is known about the Hrim-2 and its development in this past War Zone piece, which followed speculation that Ukraine might have employed some of those missiles in an attack on Russia’s Saki Air Base in 2022. It remains unclear what weapons Ukraine used in that instance.

Last year, Russian authorities in Crimea also claimed Hrim-2s had been shot down before reaching targets on the peninsula, but images that subsequently emerged of purported wreckage of those missiles did not offer hard evidence to substantiate those claims. Furthermore, Russia’s Ministry of Defense appeared to contradict those assertions by claiming it had shot down U.S.-made Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) SRBMs in the same general area around the same time.

The weapon that Zelensky mentioned today could be unrelated to Hrim-2 and there is the added potential that it might not even necessarily be what many would commonly consider to be a ballistic missile. The line between guided large-caliber artillery rockets and short-range ballistic missiles (SRBM) is increasingly blurry. SRBMs are generally defined as having maximum ranges of no more than 620 miles (1,000 kilometers). However, the U.S. military has begun using the term close-range ballistic missiles (CRBM) to refer to a subset of SRBMs with ranges under 186 miles (300 kilometers). U.S. military sources have referred to guided artillery rockets with diameters as small as 122mm (China’s WS-22 and BRE7) as CRBMs. Ukraine’s existing 300mm Vilkha-M would also easily fit this definition.

Last year, then-Minister of Defense of Ukraine Oleksii Reznikov also said that the country had a new long-range missile in development that could have a range of up to 620 miles (1,000 kilometers), but did not elaborate. Ukraine has already fielded a land-attack derivative of the Neptune ground-launched anti-ship cruise missile with a claimed range of up to 225 miles (360 kilometers) and has also been employing a growing array of longer-range kamikaze drones. Just this past weekend, Zelensky said that Ukrainian forces had begun using a new longer-ranged weapon called Palyanytsya (also written Palianytsia). Details about Palyanytsya are limited, but it has been described as a jet-powered missile/drone hybrid design.

Ground-launched stand-off munitions are also particularly important for Ukraine given that the current threat air defense environment presents serious hurdles for conducting air strikes via fixed-wing aircraft against targets deeper behind the front lines in many cases.

Ukraine has been receiving small numbers of ATACMS from the United States, which it has used to good effect. The U.S. government and Ukraine’s other foreign partners have delivered additional types of ground and air-launched stand-off munitions. Despite some recent relaxation on this front, there continue to be significant limitations imposed on the use of those weapons on targets inside Russia amid ostensible concerns about provoking further escalation and fears about the possibility of the conflict spilling over beyond Ukraine. The debate has become differently pronounced since Ukrainian forces launched their incursion into Russia’s Kursk region earlier this month. Intense discussions between Ukrainian and American authorities, in particular, are reportedly ongoing over these restrictions.

“For victory, we need long-range capabilities and the lifting of restrictions on strikes on the enemy’s military facilities,” Ukrainian Defense Minister Rustem Umerov said yesterday. “Ukraine is preparing its own response [with] weapons of its own production.”

Since Russia launched its all-out invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Ukrainian armed forces have been employing Soviet-era Tochka-U SRBMs, as well as even older Tochka types. Though Tochka and Tochka-U are not subject to any foreign stipulations about their use, they also only have maximum ranges of 43 miles (70 kilometers) and 75 miles (120 kilometers), respectively. Hrim-2’s development notably stemmed from a desire to supplant the aging Tochka series.

Having a new source of ballistic missiles that are more capable and longer-ranged than the Tochka family, and that are not subject to any Western restrictions, would be a major development for Ukraine. Ballistic missiles, in general, reach very high speeds in the terminal phase of flight, which presents distinct challenges for enemy air and missile defenses compared to other kinds of missiles, including subsonic air-breathing cruise missiles, as well as kamikaze drones. Ballistic missiles with unitary high-explosive warheads can also burrow down deeper into hardened targets or impart greater force on reinforced structures above ground like bridges thanks to that speed.

Ukrainian forces could also layer in ballistic missiles together with other types of missiles and drones in larger attacks to create even more complex scenarios for enemy forces. The Russian military routinely does this in large-scale attacks on targets.

In the future, Ukraine’s military might also be able to make use of drones operating via airborne relays or other networks to help find targets deeper behind enemy lines or inside Russia and execute them. However, Ukraine has not demonstrated its ability to conduct this kind of targeting, though it is a tactic Russian forces have been observed employing. There are reports that Russia has been using intercepted signal emissions to help with more rapid, responsive targeting of ballistic missiles against high-value targets, as well.

Russia has also notably acquired additional SRBMs from North Korea and there continue to be reports that it is working to get more ballistic missiles from Iran to bolster its own arsenal in this regard.

Ukraine’s employment of American ATACMS within the rules set by the U.S. government further underscores the potential impact of a new source of ballistic missiles that can be used without foreign restrictions. Ukrainian ATACMS strikes have already been observed forcing major changes to Russian operating procedures, especially at air bases within range of those missiles. It has also prompted Russia to rush additional air and missile defenses to the theater, including an S-500, the most advanced surface-to-air missile system in the country’s inventory today.

Ukrainian “ATACMS strikes, along with UAF [Ukrainian Armed Forces] use of U.S.-provided High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS) have required Russian forces to reinforce their air defense systems. Following the Crimea attacks [earlier in the year], Russian forces deployed their most advanced air defense system, the S-500, to protect the Kerch Strait Bridge, the DIA [U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency] stated,” according to a U.S. Special Inspector General report released earlier this month. “The S-500 system has not yet been demonstrated to be fully operational in Ukraine, which DIA views as an indication of Russia’s struggle to provide adequate air defense of Crimea. Russian forces have also redeployed several of their S-400 assets from Crimea to Belgorod to protect Russian assets from UAF HIMARS, which can now strike Russian air defenses in Belgorod.”

It does remain to be seen what new ballistic missile Ukraine may have tested and how close it is to actually being fielded operationally. However, it is not hard to see the value of such a weapon for the Ukrainian military as an additional option for launching stand-off strikes without any foreign restrictions, especially against targets inside Russia.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com