Recent satellite imagery of Belbek Air Base, near Sevastopol in Russian-occupied Crimea, shows new hardened aircraft shelters and additional construction to help shield aircraft from drone attacks and other indirect fire. This reflects a broader push by the Russian military to improve physical defenses at multiple airfields two and a half years after the launch of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

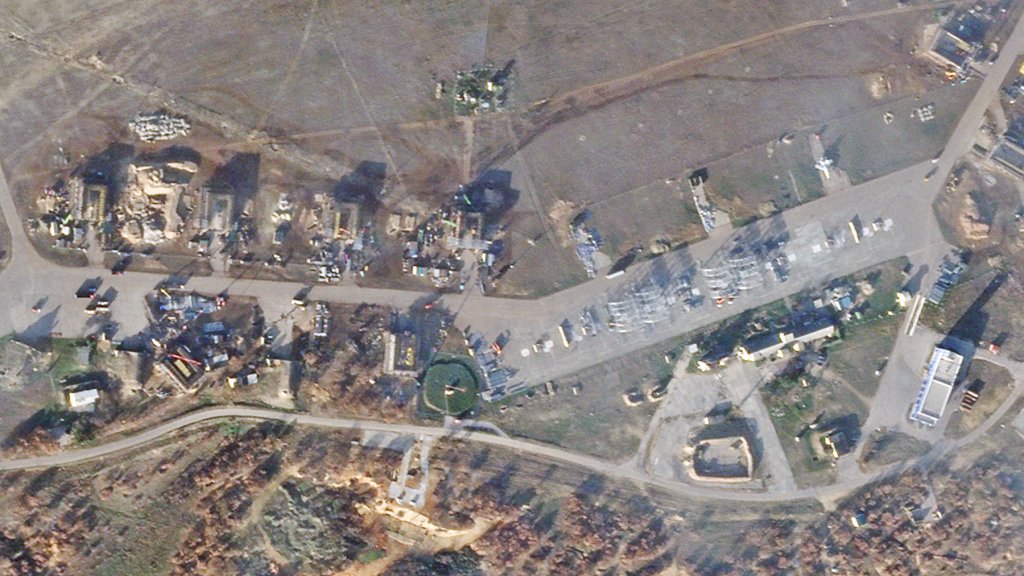

The War Zone obtained the satellite image of Belbek, seen below, which was taken on Dec. 19, from Planet Labs. Roughly 10 hardened shelters can be seen in various stages of construction over existing aircraft parking spots at the central portion of the facility. Another structure, the purpose of which is unclear, but that looks hardened, is also seen being built at a separate portion of the base.

Additional latticework for less-well-protected soft shelters is also visible on an open apron at the center of the base, as well as across from the other structure that is being built. Similar structures have been seen at other Russian air bases in the past.

Additional physical defenses at Belbek make good sense. The base has been a notably high-priority target for Ukraine since aircraft and air defenses based there help provide critical screening for the nearby Russian naval base at Sevastopol and also extend this coverage far out into the Black Sea. In addition to drone attacks, Ukrainian forces have employed U.S.-supplied Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) short-range ballistic missiles with cluster munition warheads against the facility. The base suffered a notably destructive ATACMS barrage in May of this year.

Belbek is not the only Russian base that faces Ukrainian threats and there have been growing signs of Russian efforts particularly to shield highly vulnerable aircraft currently parked out on open flight lines from attack. Around September of this year, the first evidence began to appear in Russia of efforts to protect Flanker-series combat aircraft, which had previously been left exposed on their bases. While protective structures do exist on certain Russian air bases, the large dimensions of the Flanker mean that these aircraft were never provided with suitable hardened aircraft shelters. The only exceptions were in Poland and the former East Germany, and in some of the European Soviet republics — but not in Russia.

In the second half of November, various satellite images published on social media documented the construction of hardened aircraft shelters at several Russian military airfields. These include Kursk, Akhtubinsk, Primorsko-Akhtarsk, Yeysk, Morozovsk, Millerovo, and Krymsk — now joined by Belbek.

It appears that the construction of at least 70 ‘Flanker bunkers’ began at almost the same time. It quickly became clear that a concerted construction program was underway, the scope of which finds parallels with the rapid efforts to harden airfields across Eastern and Western Europe after the dramatic success of the Israeli Air Force in the 1967 Six-Day War.

A Ukrainian research project, Frontelligence Insight, provided what may have been the first definitive publicly available evidence of new Russian bunker construction, in the form of a satellite photo taken at Kursk-Khalino Air Base on Oct. 22. Here, for example, excavation work for the foundations, the provision of prefabricated concrete parts, and initial assembly work were all clearly visible.

A satellite image of Kursk-Khalino taken on Nov. 2 was shared by Ukrainian journalist Mark Krutov and shows the full extent of the construction work at the airfield.

A further satellite image taken on Nov. 17 was provided by U.S. imagery analyst @MT_Anderson and shows the construction of hardened aircraft shelters at Krymsk Air Base.

Interestingly, from the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian military analysts and bloggers had voiced criticism regarding the vulnerability of fighter aircraft operating unprotected on Russian airfields.

Not only were critical airfields not equipped with protective structures, but there were no such hardened aircraft shelters suitable for the Flanker series in Russia.

While bombers operated by Russia’s Long-Range Aviation branch were moved to — supposedly — safer bases deeper within Russia, tactical Su-24, Su-25, Su-30SM/M2, Su-34, and Su-35S aircraft remained primarily at their operational bases. However, they relocated every few months to other airfields within the operational area and sometimes even further away from the front line.

Anti-aircraft defenses were set up at the edge of airfields, discarded aircraft were arranged as decoys and temporary blast walls were erected to protect against shrapnel and other fragments. More unorthodox measures included placing car tires on the upper surfaces of aircraft and painting aircraft silhouettes on concrete airfield surfaces. The tires, specifically, were intended to confuse image-matching seekers on Ukrainian missiles like the British-supplied Storm Shadow air-launched cruise missiles and nearly identical SCALP-EGs from France.

On the whole, this mix of countermeasures to Ukrainian long-range strikes was largely ineffective. After all, it didn’t include adequate hardened aircraft shelters — admittedly, the most expensive solution but also the best.

With each successful Ukrainian airstrike, the stunned comments and unsparing assessments from the Russian military information space became harder to ignore.

During an interview in July of this year, Russian Minister of Defense Andrey Belousov provided assurance that “a schedule for airfields has already been drawn up and shelters will definitely be built.”

This report was picked up by Ukrainian analysts, who quickly assessed that such a project would be extremely expensive — roughly $1 billion for 300 AU-19 hardened aircraft shelters of the kind that can accommodate Flankers. The AU-19 is a standardized Soviet shelter pattern developed around the Flanker during the Cold War, but, as noted, wasn’t ever built inside Russia.

The Ukrainian analysts concluded that Russia was unlikely to make this investment and would instead build shelters made of sheet steel at best, which would provide little more than weather protection.

This statement was true to the extent that a dozen such shelters were built in the winter of 2023-24 at Marinovka Air Base, located close together in a straight line, alongside the reserve taxiway. By July 2024, the second construction phase at Marinovka had begun, resulting in another dozen shelters, but this time in a more dispersed form.

A successful Ukrainian attack on Marinovka meant this construction work was never completed. In fact, the raid on Marinovka was probably a major factor behind the decision to build true hardened aircraft shelters, with work starting only a few weeks later.

Another factor was almost certainly the expectation that the Biden administration would allow Ukraine to use U.S.-produced and donated ATACMS to hit targets deep inside Russia. These missiles can hit targets of up to about 190 miles away and their use in this capacity was approved on Nov. 17. Roughly a week later, Ukraine used ATACMS in an attack on Kursk-Khalino Air Base, about 60 miles from the Ukrainian border.

The need to provide adequate protection to aircraft — especially for the U.S. military — is something that The War Zone has addressed before. Aircraft shelters with varying degrees of hardening are now very much back on the agenda globally, in response to evolving drone and missile threats. There is a growing debate within America’s armed forces and Congress about the value of building new defensive infrastructure for its aircraft, as well as investments in new active air and missile defense and tactics, techniques, and procedures. With the exception of a few forward deployment locations, the United States does not invest in robust shelters for its combat aircraft. The Russian experience from the war in Ukraine suggests that could be a mistake.

At this point, it’s worth returning to the aforementioned AU-19 hardened aircraft shelter. The AU-19 design reflected the Soviet expectation that an air war with NATO would be fought over the Central Front, with tactical aviation moving rapidly forward to keep pace with armored thrusts, with aircraft operating from bases closer to the front lines, as well as from captured airfields and improvised airstrips.

There are actually two AU-19 subdesigns. According to the Soviet designation scheme, AU-19/1 is a shelter with classic three-walled external sliding gates, while AU-19/2 has internal hinged gates, analogous to those used in certain first-generation NATO hardened aircraft shelters.

However, the new Flanker bunkers now appearing in Russia use a different design principle. For the sake of convenience, we can refer to them as AU-19/3.

There are only a few images currently available showing the excavation pits for the foundations of the new shelters, their outer structures, building materials, and assembly processes. However, none of these suggest the AU-19/3 is in any way equivalent to the original AU-19. The degree of protection probably lies somewhere between a classic hardened aircraft shelter and the kind of sheet-metal shelters seen at Marinovka.

Stefan Büttner, an expert in Russian airbase infrastructure, told The War Zone that an AU-19/3 might just be able to withstand a hit from a drone armed with a 220-pound FAB-100 bomb, “but anything more than that would inevitably lead to the collapse of the bunker itself in the event of a direct hit.”

“Based on the information currently available, the arched trusses used — presumably consisting of steel profile frames with concrete elements on top and a possible earth covering — give an impression of a construction that is far too fragile.”

This leads to the question of why Russia didn’t simply ‘reissue’ the comparatively robust AU-19 dating from the 1980s.

The design plans for the AU-19 are easily accessible and Russia has dozens of precast concrete factories whose product ranges reveal their Soviet origins. Perhaps, after all, it was simply a matter of cost that led to the current solution.

Still, the ability to protect from lighter strikes, like those delivered by drones and cluster munitions, is extremely relevant and balancing cost versus the most widespread threats does make some sense.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com