Russia is now adding a second warhead to its Kh-101 air-launched cruise missiles, widely used against targets across Ukraine. The jury-rigged solution apparently involves fitting a second charge — reportedly containing steel fragments to increase the overall destructive effect — at the expense of fuel and therefore range. It is not the first modification noted on Russian air-launched cruise missiles since the start of the full-scale invasion but it does reveal the extemporized nature of some of these adaptations.

Photos that are now circulating on social media show the wreckage of a Kh-101 — also known by the Western reporting name AS-23A Kodiak — in a field. One warhead can be seen within the mangled missile body, while another lies alongside it.

According to Defense Express, a Ukrainian security and defense publication, the missile was brought down by Ukrainian air defenses on Tuesday night, although a technical failure cannot be ruled out.

This seems to be the first solid evidence of a Kh-101 modified with a second warhead. The first claims that such a weapon was being used emerged at the end of March among Ukrainian military bloggers. It was claimed that one of the missiles had been shot down, revealing two charges, with a combined weight of around 1,760 pounds compared to around 1,000 pounds for the single warhead in the standard Kh-101.

The second warhead was said to contain steel fragments. A fragmentation charge would render the weapon more effective against personnel and softer targets as well as increasing its lethal radius and blast damage. It could also be useful if accuracy is more limited.

It should be pointed out that this is a very different solution to the kinds of twin warheads found in certain Western cruise missiles, in which a precursor charge is used to punch through hardened structures followed by a main change that detonates after breaching the target. The Russian solution is very much more crude and only intended to enhance area effects, but that’s not to say it won’t be effective above ground.

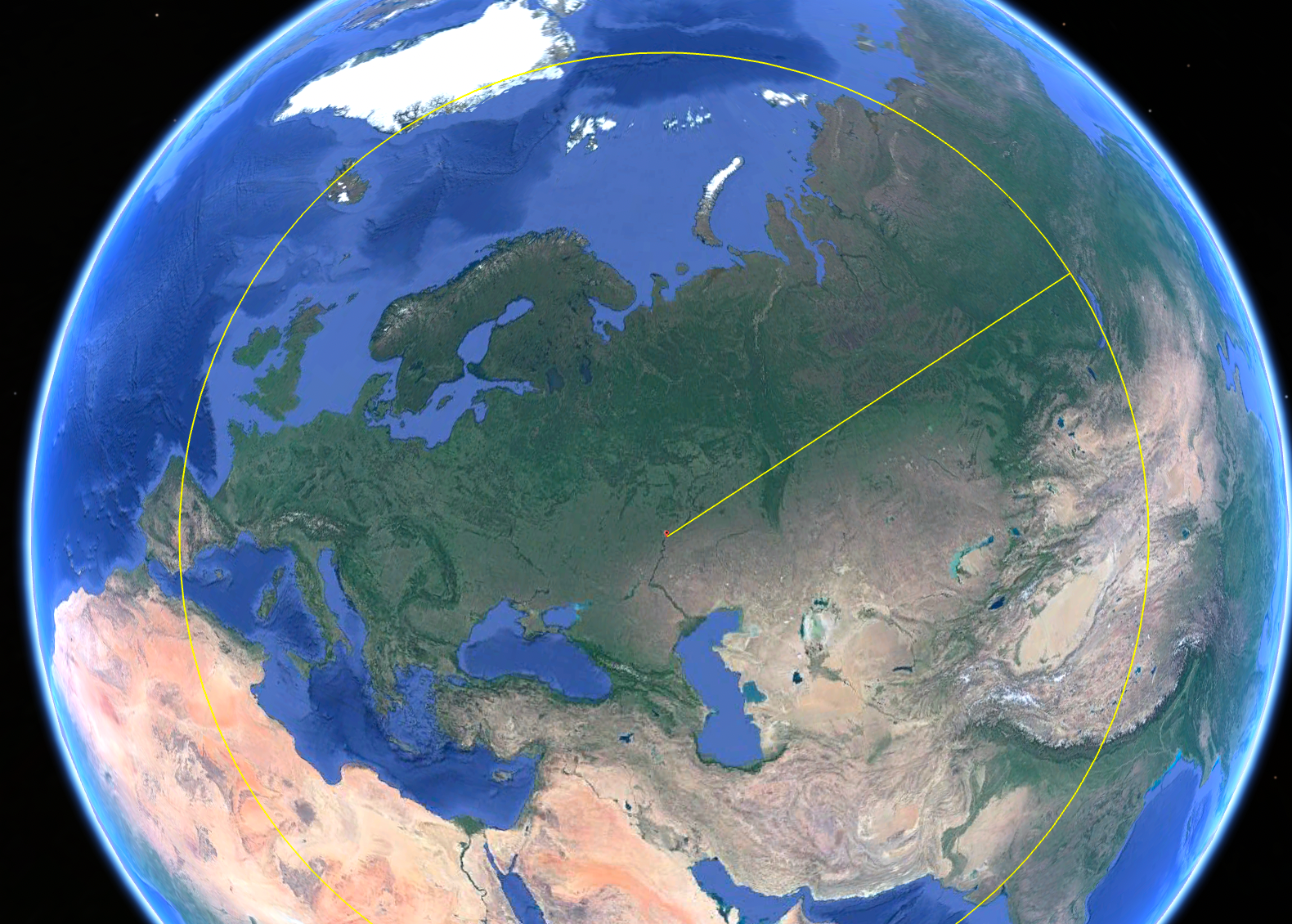

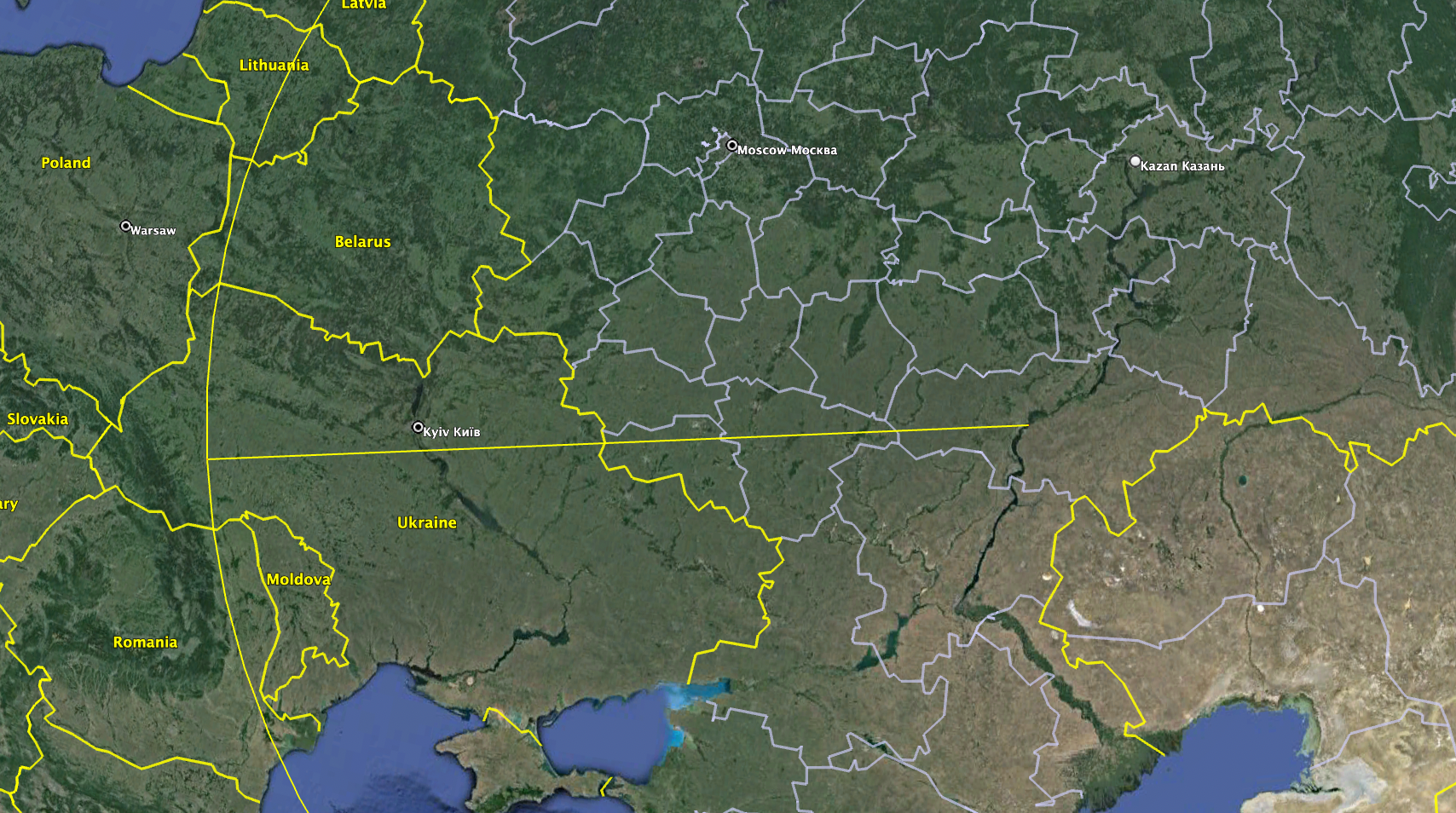

The implication of the second warhead is that the fuel capacity of the Kh-101 has been reduced since this would be the obvious way of creating more internal space. However, sacrificing fuel (and thereby range) is not a concern for Russia so long as it’s using Kh-101s to hit targets in Ukraine. With a reported maximum range of between approximately 1,870 and 2,480 miles, the basic Kh-101 can strike targets almost anywhere in Europe when launched within Russian airspace.

The Kh-101 is launched by both Tu-160 Blackjack and Tu-95MS Bear-H bombers operated by the Russian Aerospace Forces, or VKS.

According to an assessment from the U.K. Ministry of Defense, in its latest intelligence update on Ukraine, the twin-warhead Kh-101 modification has likely reduced the missile’s range by half. This would put it at somewhere between around 935 and 1,240 miles. Even at the lower end of this scale, the range would be sufficient to strike anywhere in Ukraine without the aircraft having to leave Russian airspace.

With this in mind, the decision to modify the Kh-101 in this way makes a good deal of sense for Russia, provided it doesn’t interfere with the flying qualities of the missile.

As the U.K. Ministry of Defense points out, the twin warheads should make the Kh-101 notably more lethal, a major concern for Ukraine and its civilian population, who have been bearing the brunt of Russian long-range cruise missile attacks, much of which is aimed at energy infrastructure.

The U.K. Ministry of Defense states:

“The [Russian Long-Range Aviation] Command has sought to modify its systems and tactics throughout the conflict to: increase survivability as too many missiles were being intercepted by Ukrainian air defense systems; enhance capabilities to have greater effect; and use up older missiles as the VKS had depleted more modern systems in the early days of the conflict.”

Another feature of the Kh-101 that has become obvious since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine is its ability to release decoy flares in flight. Kh-101s have been noted employing this capability in Ukraine since at least January 2023, although a self-defense function of some kind is understood to have always been present in these missiles.

There have also been reports of Russia fielding a new countermeasure-equipped Kh-101 subvariant, known as the izdeliye 504AP. According to these accounts, the revised countermeasures are intended to “jam” enemy surface-to-air missiles, which could suggest dispensers loaded with chaff.

Other modifications made to existing air-launched cruise missiles, and specifically their warheads, have been reported on the earlier Kh-55, known to NATO as AS-15 Kent.

In late 2022, reports emerged that examples of the Kh-55 were having their normal nuclear warheads removed entirely and were being used unarmed. In this capacity, their value would be as decoys that put further pressure on Ukraine’s air defenses and provide false targets, increasing the likelihood of ‘real’ missiles and drones getting through.

Even older than the Kh-55 is the Kh-22 (AS-4 Kitchen), a supersonic cruise missile with a primary anti-shipping role. Examples have been used against land targets in Ukraine, some of these missiles reportedly also being fitted with cluster warheads, as discussed in this previous article.

As we discussed in the past, the Kh-22’s advantages include its supersonic speed and terminal dive on its target, making it very hard to intercept. However, the missiles are also inaccurate against ground targets, a factor that would be mitigated somewhat by a cluster munition warhead.

All these examples reflect Russia’s willingness to adapt its legacy weapons to better suit the demands of its war in Ukraine. They also reveal the limits in terms of the availability of more appropriate missiles.

It remains to be seen if the twin-warhead Kh-101 will be a more regular feature of Russia’s strikes on Ukraine. But if it does prove viable, its additional destructive power will be bad news for Ukraine and will once again highlight the country’s need for more and more effective air defense systems to counter these and other threats.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com