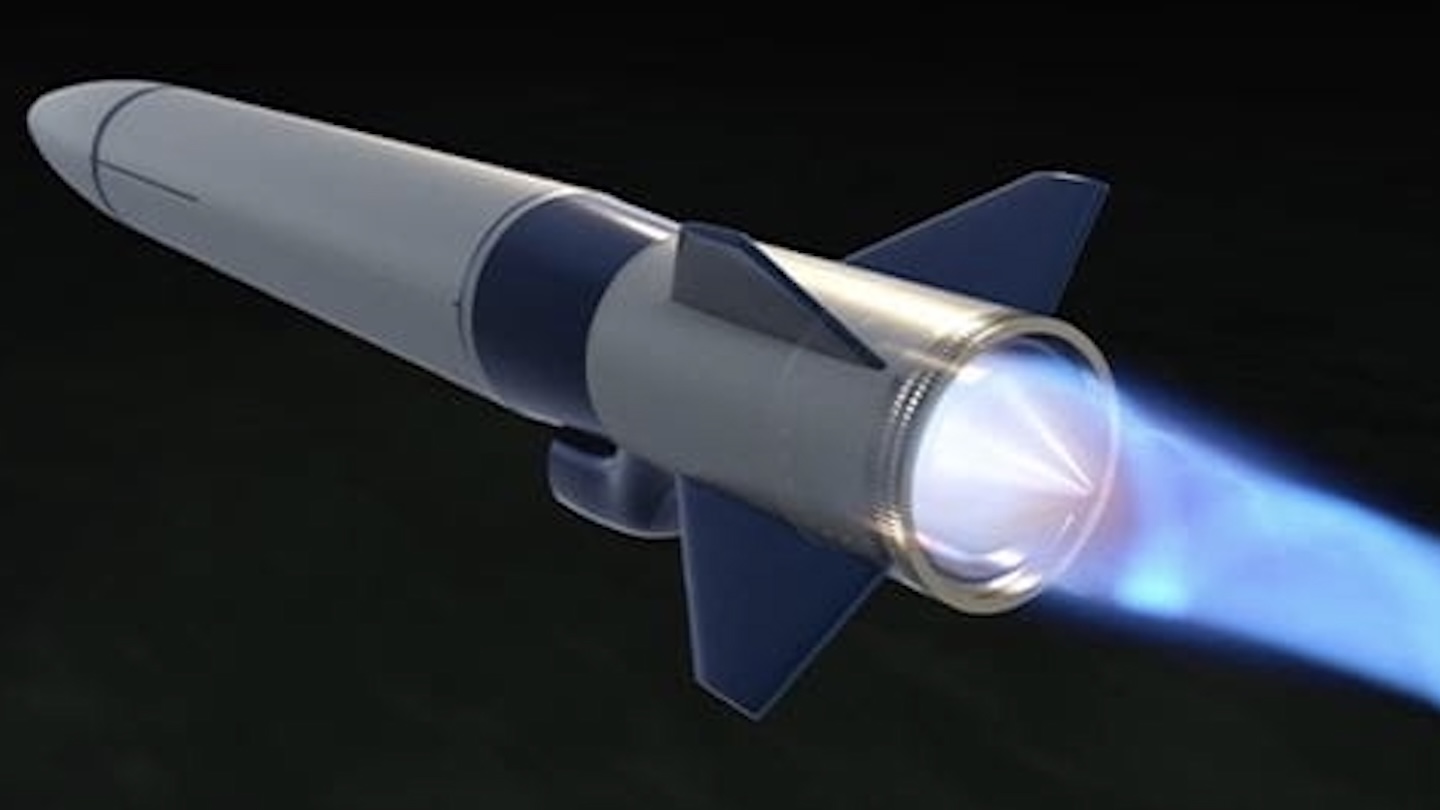

A novel type of jet propulsion, a rotating detonation engine (RDE), has been successfully tested by Pratt & Whitney. The development could be highly significant for the U.S. military, with RDE technology at the center of the project called Gambit, which aims to provide a propulsion system for a mass-producible, low-cost, high-supersonic, long-range weapon for air-to-ground strike.

RTX — of which Pratt & Whitney is a business unit — announced today that a series of tests on the RDE has been completed at the RTX Technology Research Center in Connecticut. Previously, RDE propulsion systems had only been run in the form of small prototypes.

Next, the company says it will move on to integrated engine and vehicle ground tests to be conducted with the U.S. Department of Defense “in the coming years.”

“Our testing simulated aggressive assumptions for how and where the rotating detonation engine needs to perform,” Chris Hugill, senior director of Pratt & Whitney’s GATORWORKS development team, said in a media release about the latest campaign. “This testing validated key elements of Pratt & Whitney’s design approach and provides substantiation to continue RTX vehicle and propulsion integration to accelerate future capabilities for our customers.”

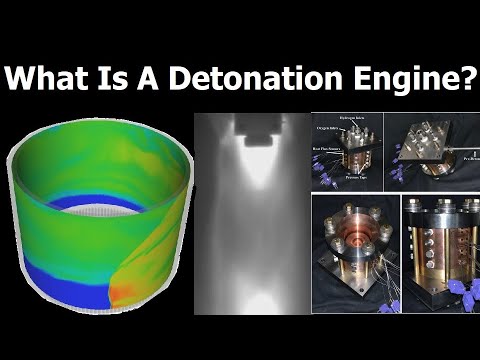

In terms of how they operate, RDE propulsion systems have significant differences compared to a traditional turbojet or turbofan engine and hardly require any moving parts.

In turbojet or turbofan engines, air is fed in from an inlet and compressed, and then is mixed with fuel and burned via deflagration (where combustion occurs at a subsonic rate) in a combustion chamber. This process creates the continuous flow of hot, high-pressure air needed to make the whole system run.

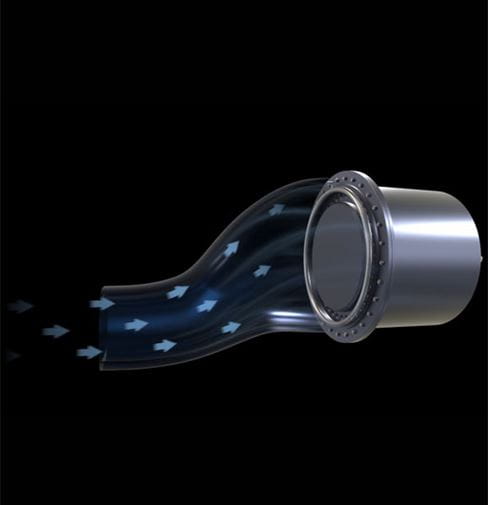

In an RDE, the combustion (which happens at a supersonic rate) occurs in an enclosed, annular (ring-shaped) chamber. During flight, fast-moving air is sucked into the chamber and a mixture of fuel is injected into it. The injection ignites a flame-like detonation wave that travels around the ring for as long as fuel is injected, in a thermodynamic cycle, providing propulsive thrust.

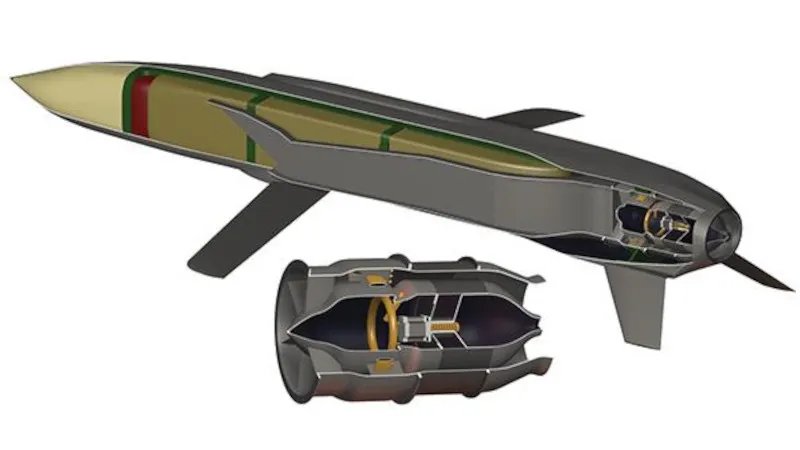

The advantages of an RDE include high thermal efficiency and more power, which means the engine can also be smaller, lighter, and more cost-effective. After all, most longer-range air-to-ground missiles today require scaled-down jet engines that are single use, making this a much less cost-effective propulsion setup.

In a practical application, such as a missile, since an RDE is more compact than a traditional engine, there is more space for fuel, giving longer range. Additional capacity can also be used to house sensors, warheads, or other payloads.

A video provides a more detailed walkthrough of the rotating detonation engine concept:

Pratt & Whitney’s current work on the RDE is based on a contract from the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), which called upon Raytheon (now RTX) to develop this kind of propulsion for “effectors” — primarily missiles.

The initial work was conducted by the RTX Technology Research Center, which then teamed up with Pratt & Whitney to mature the technology. Ultimately, the RDE is planned to power a new generation of effectors, including missiles designed and developed by Raytheon.

Experimentation with RDE concepts dates back to the 1950s, but actually creating a workable engine of this type had proved elusive until very recently, at least publicly.

According to RTX, there were two main technological hurdles to overcome before the RDE could be successfully demonstrated.

The first challenge involved the fuel injection component. Simply put, the balance of air and fuel in the chamber has to be perfect, consistently, to ensure an effective detonation wave.

The second challenge, RTX says, was designing and manufacturing parts that relied on advanced techniques, including additive manufacturing and physics-based modeling.

Overall, RTX’s work on the RDE is closely related to a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) project called Gambit. The main aim of this effort is “to develop and demonstrate a novel rotating detonation engine propulsion system that enables a mass-producible, low-cost, high-supersonic, long-range weapon for air-to-ground strike in an anti-access/area denial (A2AD) environment.”

Gambit was launched in 2022, and the following year, Raytheon secured a contract from DARPA to develop and demonstrate a practical RDE for the Gambit project.

While RTX talks about the potential for the rotating detonation concept to be harnessed in the broad category of “effectors,” it would appear to be of greatest significance for future missiles, like the ones envisioned under DARPA’s Gambit project.

Missiles using this kind of propulsion arrangement would achieve greater efficiency and lighter (and potentially smaller) missile bodies, which in turn would allow for enhanced performance — especially in terms of range — and/or payload capacity.

Future missiles that are able to achieve efficient sustained supersonic speed over long distances would be of considerable importance in terms of time-sensitive mission requirements. Above all, any future high-end conflict in the Pacific, such as one against China, would automatically involve all sorts of operational demands across a broad area, much of it covered in water.

“The government is looking for missiles that go faster and fly farther,” Beata Maynard, an associate director in Advanced Military Engines at Pratt & Whitney, said in a media release today. “Combining Pratt & Whitney propulsion technology with a Raytheon vehicle could result in a weapons system that addresses warfighters’ immediate needs.”

RDE is not the only exotic propulsion system that’s being considered to power future missiles, effectors, and even aircraft. There are also ramjets and dual-mode ramjets (the latter also using RDE technology), which can confer hypersonic performance. Hypersonic speed is defined as anything above Mach 5.

While there’s clearly an appetite for the kinds of advantages that a rotating detonation engine would confer on a variety of future missiles, it should be recalled that this technology is very much still in its infancy. There will be plenty more hurdles to overcome before propulsion systems of this kind find their way into actual missiles.

However, once mastered, this technology promises to significantly help lower the cost and accelerate the production, on top of the various performance advantages.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com