Eighty years ago this week, a truly bizarre air-to-ground weapon was successfully employed in combat for the first time. It was so strange, in fact, that the Allied pilots who first encountered it in the skies over Normandy were not entirely sure what it really was.

Among a string of unorthodox — and sometimes highly sophisticated — weapons hastily fielded in the last months of World War II, Germany’s Mistel composite aircraft were among the most extraordinary. However, these combinations of unmanned bombers packed with explosives and manned fighters to guide them toward their target were destined not to have any effect on the course of the war.

The basic concept of strapping one aircraft to another to create a composite was not new. During the interwar period, it emerged as a way of extending the range of aircraft during peacetime. In particular, there was a focus on composite seaplanes and flying boats, to extend the reach of commercial services across oceans. Solutions like the British Short Mayo Composite involved launching a small, long-range seaplane from the top of a larger carrier aircraft, while in flight, to extend the overall range.

However, the first experiments with aerial refueling suggested a much more practical answer to the problem of long-distance flights and the outbreak of World War II rendered commercial composite aircraft obsolete.

By 1942 it was clear to German planners that the course of the war was not in their favor and there began a wide variety of efforts to develop new and innovative weapons that might have a chance of stopping Allied advances, which would enter crisis mode once a new front was opened up in the West.

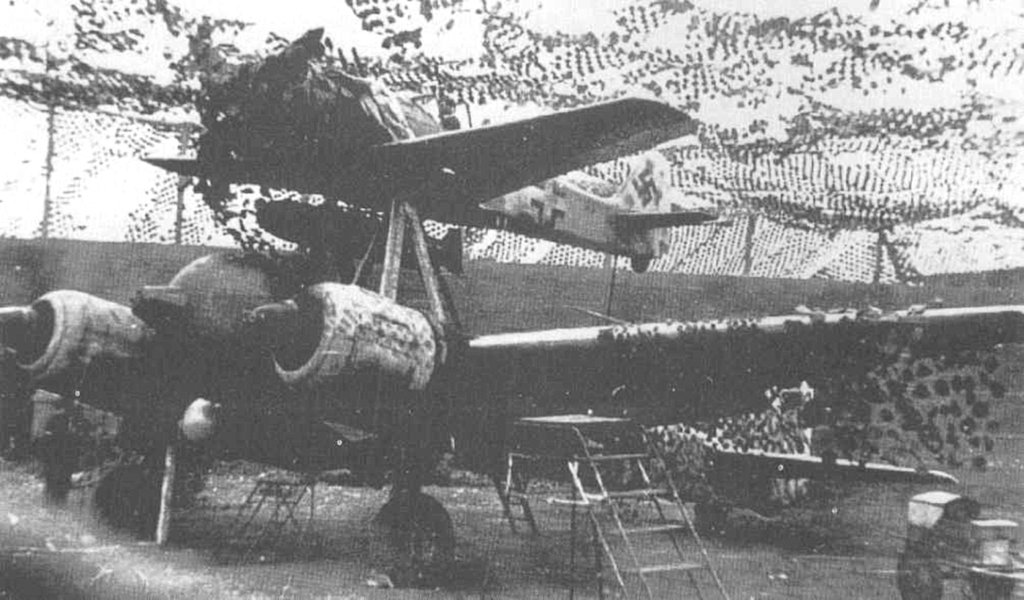

Under the plan known as Mistel (meaning mistletoe, a parasitic plant that grows on a tree), war-weary Junkers Ju 88 bombers would be adapted to become pilotless missiles, onto which would be attached piloted Messerschmitt Bf 109 or Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighters. The composite aircraft would launch entirely under the control of the fighter and be brought to the target, after which the bomber/missile component would be released on the correct trajectory, leaving the fighter free to (hopefully) return to base.

The overall idea also highlighted one glaring omission in the Luftwaffe order of battle, since — in contrast to the Americans and British — long-range heavy bombers had been a very low priority. Since the Mistel Ju 88 was now on a one-way mission, its full fuel load could be expended en route to the target, a journey that would be achieved without the fighter component having to use its own fuel. German reports suggested that a range of 1,500 miles was technically feasible.

As well as its long range, the concept promised to deliver enormous destructive effect for relatively low cost and would use up bomber airframes that were no longer fit for more traditional missions. While this was the original concept, the desperate situation in the war ultimately led to factory-fresh Ju 88s also being completed as Mistel components and being delivered as such to the Luftwaffe.

The key to the destructive power of the Mistel lay in the massive hollow-charge warhead that replaced the cockpit section of the Ju 88. A hollow charge, also known as a shaped charge, essentially features a large open cavity between the main explosive charge and the front of the projectile. An inverted cone-shaped metal liner is inserted into the explosive charge — in the case of the Mistel, either copper or aluminum. When the charge goes off, it expands outward, turning the liner into something like a high-speed metal dart that then punches through the target.

Today, hollow-charge warheads are best known for their use in much smaller-sized applications, like anti-tank missiles and rockets.

In the Mistel, however, the hollow-charge warhead weighed close to 4,000 pounds and was expected to be able to punch through multiple feet of reinforced concrete after being triggered by a long standoff fuse. In tests, the warhead achieved remarkable results: It was reportedly able to defeat 26 feet of steel or 66 feet of ferro-concrete.

This would make the Mistel especially suitable for attacking major warships, in particular those of the British Royal Navy, the size and strength of which meant it was a continuous thorn in the side of the German war machine.

The first Mistel experiments involved smaller-scale aircraft, initially with a Klemm Kl 35A light sports plane on the back of a DFS 230A glider, a combination which required a Junkers Ju 52/3m transport to tow it into the air.

As the concept was refined, successively bigger upper components were tested, the Klemm giving way to a Focke-Wulf Fw 56 Stösser fighter trainer and then a Bf 109. Once the powerful fighter was included, the experimental Mistel combination was even able to take off solely under the power of the fighter’s single engine, although it’s likely that this was without the warhead fitted.

The all-important release mechanism was also mastered. The struts supporting the fighter were of sufficient length that its propeller wouldn’t impact the Ju 88 and electrically detonated explosive ball joints were used to separate the two aircraft. The rear strut was designed to collapse just before this happened, lifting the nose of the fighter to ensure it was at the right attitude to climb away safely.

Bigger problems were experienced with fitting the equipment needed to pass control and throttle inputs to the Ju 88 into the fighter’s small cockpit. Flight controls had to be duplicated, with control inputs delivered to the Ju 88 using electric cables. The throttles for the bomber, meanwhile, were controlled using mechanical actuators.

Somewhat surprisingly, given the risks involved, it was apparently decided to remove the brakes from the Ju 88 to save weight and reduce complexity. This was all very well if the mission was completed successfully, but an aborted takeoff must have been a terrifying prospect for the pilot in the upper component.

Once Mistel combinations began to be fielded by the Luftwaffe, in May 1944, the initial target selected was the Royal Navy anchorage at Scapa Flow, the United Kingdom’s chief naval base, off the Scottish coast.

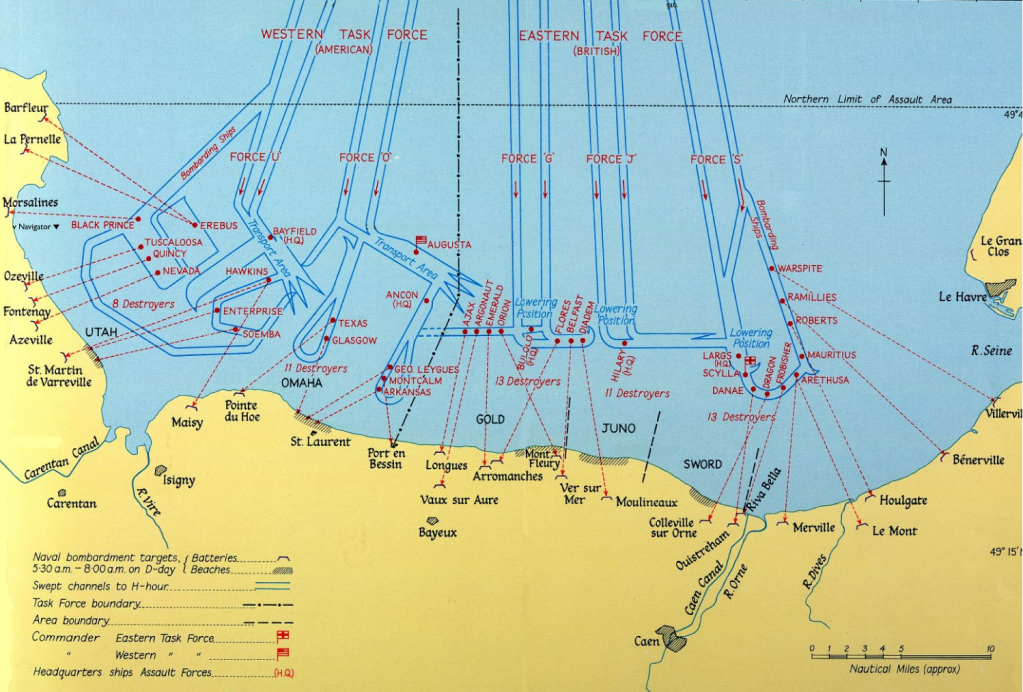

These plans were rapidly superseded by D-Day and the Mistel force was now prepared to be used against the Allied invasion force off the coast of Normandy. Here, the big challenge would be Allied airpower, dominant over the beachhead and deep into Normandy. Daylight Mistel operations would be highly risky but were not unheard of.

On the evening of June 14, a Mistel that had been tasked with targeting the Allied fleet ran into resistance in the skies over northern France and provided Allied aircrew with one of their first glimpses of the composite aircraft.

The incident was recalled by Flt. Lt. Walter Dinsdale, who had been flying a Royal Canadian Air Force Mosquito fighter-bomber, in Robert Forsyth’s book Luftwaffe Mistel Composite Bomber Units.

“It was a very awkward thing, and it lumbered along like an old hippo at about 150 mph. I recognized it as a Ju 88 but couldn’t figure out what the thing on top was. I thought it was one of their glider bombs mounted іп a new way. It was on top, mounted between the rudder and the main wing. My first short burst hit the starboard wing and cockpit of the Junkers. I thought I had killed the pilot, but, of course, there was no pilot as the whole thing is controlled from the fighter on top. Carrying on for a few minutes, circling to port with the fire increasing, he then dropped away and crashed behind the German lines. The explosion lit up the countryside for miles around.”

The first successful Mistel mission known to have been launched was on the night of June 24/25, 80 years ago this week.

According to a detailed account of the mission from Forsyth, five of the 12 Mistel combinations then available were prepared, together with manned Ju 88 pathfinder aircraft and fighter escorts.

The target was the Allied convoy in the Bay of the Seine, which was expected to include the Royal Navy battleship HMS Nelson, which had been bombarding German positions inland and providing fire support to advancing Allied troops, but which had, by this point, sailed away.

In the same source, Oberleutnant Horst Rudat, commander of Einsatzstaffel KG 101, recalled the mission:

“Four aircraft took off successfully in the early evening, when encounters with the enemy’s day fighters were no longer expected and before night-fighters made their appearance. The entire operation was cloaked in secrecy. German anti-aircraft batteries along our route were only informed of our mission at the very last minute and were ordered not to fire. It was my bad luck that one of these batteries had not been informed in time. We were still climbing when, at a height of 1500 meters [4,900 feet], we came under fire. My left engine was hit and stopped. I remember the feeling of sitting on top of an enormous warhead and being shot at by our own flak. Because I was unable to feather the propeller of the dead engine, I lost speed rapidly and was unable to keep up with the other three Mistel. In the meantime, it had grown dark.”

“West of Le Havre, I noticed a British night-fighter and I became conscious of the fact that I had no means of defending myself — my guns had been removed. Because my Ju 88 tended to want to turn continually to the left, I decided to make a direct attack on the numerous landing craft saturating the coastline. Something would definitely be destroyed, even though I could not claim success for the destruction of a designated target. After aiming the Ju 88, I separated and immediately turned inland to escape the night-fighter.”

Another of the pilots experienced control difficulties and was forced to release the bomber component early, the Ju 88 plummeting into the sea.

At least one Ju 88 was launched successfully, however. Released from a height of 800 feet, it exploded close to the Royal Navy frigate HMS Nith, anchored off Gold Beach. The attack killed nine crew and injured 27 more, while the starboard side of the ship was caved in and peppered with steel fragments, although it wasn’t sunk.

Later, another plan was made to use the Mistel force to attack the Royal Navy at Scapa Flow and elements were deployed to Denmark in anticipation of this. However, the sinking of the German battleship Tirpitz by the British changed the overall maritime balance of power and made this mission redundant.

For a time, the Mistel force was barely used but, in the meantime, it was brought under the control of the Luftwaffe’s special missions unit, KG 200, which was engaged in a wide range of clandestine work, including flying captured Allied aircraft that were used for, among others, dropping agents behind enemy lines.

By early 1945 the tide of the war had well and truly turned against the Germans and the Mistel force was called upon again. With the Allies in the west poised to cross the Rhine and the Soviets in the east pressing toward Berlin, thought turned to attacks on long-range strategic targets, specifically power stations around Moscow and Gorky. These challenging missions would involve an outward flight of around 10 hours, the release of the bomber component, followed by the fighter flying another five or so hours to the relative safety of Latvia. The mission was known as Operation Eisenhammer but was stopped in its tracks when U.S. bombers destroyed 18 Mistel combinations on the ground at the airfield of Rechlin, northwest of Berlin.

At this point, the Mistel was selected for a new target set, namely the bridges that were vital for the Allied advances that were now driving into the heart of the Reich from east and west.

With the Red Army less than 50 miles from Berlin, it was decided to use the Mistel to strike bridges over the Oder and Neisse rivers on the eastern approaches to Germany. A Mistel attack was launched against the bridge over the Oder at Görlitz. Although a malfunction forced one pilot to jettison their Ju 88 early, another two scored direct hits, and a fourth a near miss.

Ultimately, however, the Mistel combination was proving too costly for the hard-pressed German military. The raid on the bridge at Görlitz had consumed six Ju 88s, two Bf 109 fighters, and, most critically, an enormous amount of fuel. While the bridge was damaged, it only held up the advancing Soviet troops by two days.

Other, sporadic missions continued in an effort to slow down the Soviet advances over the Oder, Neisse, and Warthe rivers during the last weeks of the war, but with mixed results. In total, around 250 Mistel combinations were completed, many of them never used.

Before the end of the war, the Allies also put to use surplus bombers as one-way attack aircraft.

Most notably, the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) modified time-expired Boeing B-17s and other bombers, packing them with explosives and operating them under remote control from other aircraft once the pilot and co-pilot bailed out. Much like the Mistel, the project proved expensive and ultimately unsuccessful — as well as being notably hazardous for the crews involved.

For both the Allies and the Germans, it was clear by the end of the war that far more promise lay in the potential of purpose-designed standoff air-to-ground weapons, like the German Henschel Hs 293 and the U.S. VB-3 Razon, both of which were radio-guided glide bombs that would prove highly influential on subsequent developments.

Like so much in the German war effort, the Mistel program was too little, too late.

Meanwhile, the concept of composite aircraft has never fully disappeared, especially in the realm of space exploration. On several occasions, the Space Shuttle prototype Enterprise was released in mid-air from NASA’s 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, as you can read about here. Today, it’s left to the remarkable Stratolaunch Roc — the world’s largest plane in terms of wingspan — to continue the composite aircraft legacy, hauling rockets and other payloads up to altitude before they continue into space.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com