The U.S. Air Force has no plans to acquire stealthy uncrewed combat air vehicles (UCAV) capable of operating with very high degrees of autonomy independently of crewed aircraft. The service is instead focused on buying large numbers of Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) drones that it plans to employ tightly tethered to piloted aircraft. This is in spite of the potential value of fully autonomous UCAVs, especially in a potential high-end end fight across the broad expanses of the Pacific against China, which is investing heavily in drones of this kind.

The War Zone has been keeping a close eye on the still-widening UCAV gap between the U.S. military and its Chinese counterparts for years now. For a time, stealthy flying wing UCAVs looked on track to become a revolutionary new capability for America’s armed forces before suddenly disappearing completely from the public eye in the United States without any real explanation more than a decade ago, as you can read more about in this past feature. Our own Howard Altman took the opportunity to ask Gen. David Allvin, Chief of Staff of the Air Force, about the issue yesterday at a roundtable for members of the media on the sidelines of the Air & Space Forces Association’s (AFA) main annual conference outside of Washington, D.C.

“I would say that our conception for the Collaborative Combat Aircraft … it’s part of the human-machine teaming,” Allvin said. “What we think is the most value for the types of fights that the Air Force is going to be expected to participate with a joint force in is in this affordable mass, in this first increment of Collaborative Combat Aircraft, following on with some combination to be able to do either collective or disaggregated air superiority.”

“If there’s a mission that we think is best served by something like that [a flying wing-type UCAV], we’ll certainly look at investing in it,” he continued. “But our focus right now is in these Collaborative Combat Aircraft to do the human-machine team.”

The U.S. Air Force had been very active in the development of flying wing UCAVs, and publicly so, in cooperation with the U.S. Navy, around the turn of the last century. However, by the early 2010s, the Air Force’s interest in such capabilities, at least in the unclassified domain, had completely evaporated. The Navy pushed ahead alone for a short time before it too abandoned its UCAV efforts. As already noted, this was a still very curious series of events.

“So, to do something that is independent of that [human-machine teaming], we have some capabilities,” Gen. Allvin did add, which might allude to ongoing work on some level in the classified realm or at least some degree of preservation of work from previous programs. The Air Force has continued to develop and field stealth flying wing drones configured for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions over the years. This includes Lockheed Martin’s RQ-170 Sentinel and Northrop Grumman design commonly referred to as the RQ-180.

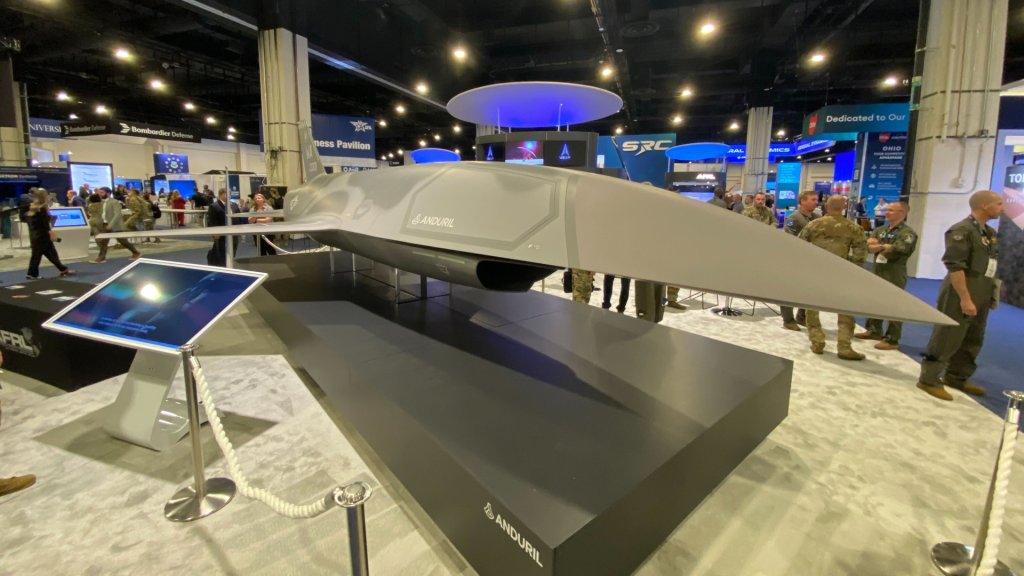

Allvin’s comments are very much in line with those from other senior Air Force officials when it comes to plans for future uncrewed combat aviation capabilities. As it stands now, the service has laid out a vision of operating large numbers of less complex and lower-cost CCAs in a completely different category from flying wing UCAVs, which will be very directly overseen by a controller in another aircraft. General Atomics and Anduril are currently working on two separate designs as part of the CCA program’s initial iterative development cycle, which is expected to be the first of many such “increments.”

“As we go forward, I expect there’ll be a strike aspect to CCAs, as well, but initially we’re focused on air superiority and how to use the CCAs in conjunction with a crewed aircraft to achieve air superiority,” Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall said at a separate media roundtable The War Zone and other outlets attended on the sidelines of the AFA conference yesterday. “When we do the ops analysis, there’s a really clear advantage of that.”

“I was just talking to our program manager downstairs… and we were talking about what we think the number of aircraft, CCAs, that can be controlled by a crewed aircraft [is]. And I initially started out with a range of three to five,” Kendall continued. “We’re talking about bigger numbers than that now. So we’re moving towards greater reliance on uncrewed aircraft working with crewed platforms to achieve air superiority and to do other missions.”

“One of the things you have to have if you’re going to use CCAs and have them be armed and … Lethal is that they have to be under tight control. And, for me, one of the elements of that needs to be line-of-sight communications. And I think that that’s an important thing to have in the mix, secure, reliable line-of-sight communications. We’re not going to have aircraft going out and doing engagements uncontrolled,” the Air Force’s top civilian added. “So the default, if they lose communications, would be for them to return to base, which takes them out of the fight. So we don’t want that to happen. And when they do do engagements, … we want them under tight control. So I think the mix of crewed and uncrewed aircraft, I think, is going to be the right answer for the foreseeable future.”

Kendall also suggested that more narrowly focusing the design of a planned crewed sixth-generation stealth combat jet around the drone controller mission might offer a path to dramatically reduce the unit cost of those aircraft. He has left the door open in the past to the potential for this aircraft, which is part of the larger Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) initiative, to be pilot-optional or even entirely uncrewed in the end but has also said a crewed design of some kind is still likely to emerge. The NGAD combat jet program is currently on hold while a complete reassessment of the underlying requirements is conducted, as you can read more about here.

“The F-35 kind of represents, to me, the upper bounds of what we’d like to pay for an individual [NGAD combat jet] aircraft,” the Secretary of the Air Force said yesterday. “I’d like to go lower though … once you start integrating CCAs and transferring some mission equipment and capabilities [and] functions to the CCAs, then you can talk about a different concept, potentially, for the crewed fighter that’s controlling them.”

The original NGAD combat jet concept that is now under review has been expected to have a unit cost roughly three times that of an F-35. Kendall said that the Air Force could still pursue a design like that if the ongoing reassessment determines that to be the best course of action. The average unit price of an F-35 differs by variant and fluctuates regularly, but is generally pegged at between $80 and $90 million based on publicly available information.

“We are maturing our approach to autonomy so it’s getting better,” Andrew Hunter, Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology & Logistics, told The War Zone and other outlets at his own roundtable at the AFA conference yesterday. “So it’s not going to be static.”

At the same time, “we know two things about autonomy,” Hunter explained. “One is laws of war require us to have, you know, human engagement in key decisions involving employment of weapons and other key decisions. So we have to have that. We have to have that human engagement, the ability to do that. The second is [that] we know that our ability to create systems that can operate autonomously and do missions well is something that is still maturing.”

The Air Force’s future vision of CCAs operating under the tight control of human operators in other nearby aircraft stands in stark contrast to a steady stream of UCAV developments, especially with regard to stealth flying wing types, in China in recent years. There is growing evidence that testing of one particular design, the GJ-11 Sharp Sword, is now significantly expanding in scale and scope. Work to date on the GJ-11 has already pointed to plans to operate the UCAVs in highly autonomous cooperative swarms, as well as teamed with crewed combat jets. Shipboard operations from aircraft carriers and big deck amphibious assault ships also increasingly look to be in the Sharp Sword’s future.

Satellite imagery The War Zone obtained and otherwise reviewed from Planet Labs shows a pair of GJ-11s have been operating very actively together from Malan Air Base in recent months. Malan, situated in China’s far-western Xinjiang province, is a major drone testing hub. The War Zone recently reported on these and other Chinese UCAV developments in more detail, as you can find here.

After we published that story it also came to our attention that other satellite images had caught a GJ-11, along with other military drones, at China’s Daocheng Yading Airport. Located in the Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of China’s Sichuan province at an altitude of approximately 14,472 feet, Daocheng Yading is the highest civilian airport in the world. It is also less than 250 miles from the border with India, one of China’s chief regional competitors.

The dichotomy is even more striking considering the U.S. military currently uses its Chinese counterparts as its chief “pacing threat” to plan against. More exquisite autonomous stealthy UCAVs would be more expensive and complex than the CCAs that the U.S. Air Force, as well as the U.S. Navy, is planning to acquire, but would also come along with greater lower observability (stealthiness), range, and payload capabilities that could be very valuable in a future high-end fight across the broad expanses of the Pacific. What is known about the Air Force’s evolving CCA requirements has already pointed to significant debate about the desired range and other capabilities for those drones.

Developing a true UCAV would also not preclude plans to field lower-tier CCAs designed to operate more closely together with crewed platforms. China’s People’s Liberation Army is also actively pursuing drones in CCA-like categories, along with ones like the GJ-11.

It’s worth noting here that China is not alone in actively pursuing flying wing UCAVs, either. Russia, India, Turkey, and others are doing so, as well.

In addition, China is also surging forward in its work on autonomous uncrewed capabilities, and not just in the air domain, and technologies to support those developments, especially when it comes to artificial intelligence and machine learning. There have now long been questions about whether the Chinese government will concern itself to the same degree as the United States and many other countries when it comes to the moral and ethical questions about autonomous systems capable of carrying out lethal attacks. These will continue to be pressing questions broadly as uncrewed platforms, even very low-tier ones, with artificial intelligence-driven targeting and other capabilities continue to proliferate, as The War Zone has explored in detail recently.

As our own Tyler Rogoway wrote back in 2018:

“I can tell you that our potential enemies have no trouble defining these systems or embracing their game-changing capabilities, regardless of the moral ambiguity that may go along with it. What we are left with is potentially a missed opportunity of epic proportions. We could be spending considerable effort not simply trying to build a better fighter jet but to leap-frog the enemy in full by totally changing the game via investing in advanced unmanned air combat technologies. “

“Instead it seems the USAF and the Navy are concentrating on keeping a human totally in the loop via manned-unmanned teaming and other concepts. This is fine for some interim applications but totally keeps the great potential of autonomous swarming UCAVs under lock and key, and therefore stunts their inevitable growth.“

Six years later, the U.S. military’s focus remains unchanged and the Air Force has now confirmed it has no higher-end UCAVs in the works, at least publicly, even as the gap with China in this regard continues to widen.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com