A new independent report says that U.S. airbases have been left worryingly vulnerable, especially in the Indo-Pacific region, by a lack of investment in new hardened aircraft shelters, or even unhardened ones. In contrast, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has more than doubled its total number of hardened and unhardened aircraft shelters in the past 15 years or so, along with a major expansion of other airbase infrastructure. Other countries, including Russia, are increasingly doing the same. This comes amid a heated debate between the U.S. military and Congress over the right mix of active and passive base defenses needed to succeed in a future high-end conflict, such as one against China in the Pacific, which TWZ has been following closely.

The Hudson Institute think tank in Washington, D.C., published the report, titled “Concrete Sky: Air Base Hardening in the Western Pacific,” yesterday. Its primary authors are Hudson’s Timothy Walton and Thomas Shugart from the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), a separate think tank.

“The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has consistently expressed concern regarding threats to airfields in the Indo-Pacific, and military analyses of potential conflicts involving China and the United States demonstrate that the overwhelming majority of US aircraft losses would likely occur on the ground at airfields (and that the losses could be ruinous),” the report says in its executive summary. “But the U.S. military has devoted relatively little attention, and few resources, to countering these threats compared to developing modern aircraft.”

By the report’s accounting, the U.S. military has added two hardened aircraft shelters (HAS) and 41 of what it refers to as “unhardened individual aircraft shelters (IASs),” at airbases within 1,000 miles of the Taiwan Strait since the early 2010s. Expansion of those same facilities has been otherwise limited, with the addition of only one runway, one major taxiway, and 17% more ramp area overall.

“Since the early 2010s, the PLA has more than doubled its hardened aircraft shelters (HASs) and unhardened individual aircraft shelters (IASs) at military airfields, giving China more than 3,000 total aircraft shelters — not including civil or commercial airfields,” the new report from Hudson says. “This constitutes enough shelters to house and hide the vast majority of China’s combat aircraft. China has also added 20 runways and more than 40 runway-length taxiways, and increased its ramp area nationwide by almost 75 percent.”

“In fact, by our calculations, the amount of concrete used by China to improve the resilience of its air base network could pave a four-lane inter-state highway from Washington, D.C., to Chicago[, Illinois],” it continues. “As a result, China now has 134 air bases within 1,000 nautical miles of the Taiwan Strait — airfields that boast more than 650 HASs and almost 2,000 non-hardened IASs.”

The report does acknowledge that IASs do not provide anywhere near the same level of protection as true HASs, which are costlier. It also makes clear that shelters, hardened or otherwise, are just one part of a larger base defense equation. However, its authors argue that robust passive defenses are the most cost-effective single measure that can be taken to provide critical added resiliency against attacks and help provide a key foundation for other concepts of operations.

Hudson’s report estimates that buying just one fewer B-21 every year for the next five years could free up enough funds to construct 100 HASs. A similar reduction in purchases of F-15EXs or F-35As could yield the resources required to build 20 more HASs annually. The estimated unit cost of the B-21 is pegged at between $600 and $800 million based on publicly available information. As of 2023, the price tag for a single F-15EX was nearly $94 million, while the average unit cost across all three variants of the F-35 was said to be around $82.5 million.

Furthermore, “a $4 million fully-enclosed, substantial hardened aircraft shelter [for fighters] that may last for decades costs as much as a single Patriot surface-to-air missile or 1/20 the cost of an $80 million fighter aircraft that the HAS might otherwise protect,” the report adds, quoting a separate white paper on airbase defense that the Air & Space Forces Association’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies published in July 2024.

In addition, “while non-hardened IASs do not provide the same degree of protection as HASs, some of them may provide at least partial protection from shrapnel,” the report adds. “IASs may also make it more difficult to determine the number and types of aircraft at a base, potentially masking a pre-conflict surge of aircraft, and make both strike planning and post-strike damage assessment more challenging.”

As TWZ highlighted in the past, the ability to better shield planes exposed on the flight line from even more limited threats like shrapnel, including that produced by relatively small warheads on kamikaze drones and cluster munitions, is still very valuable. By targeting aircraft sitting out in the open, an adversary could well prevent them from ever entering the fight, even with limited attacks, such as ones involving weaponized commercial drones.

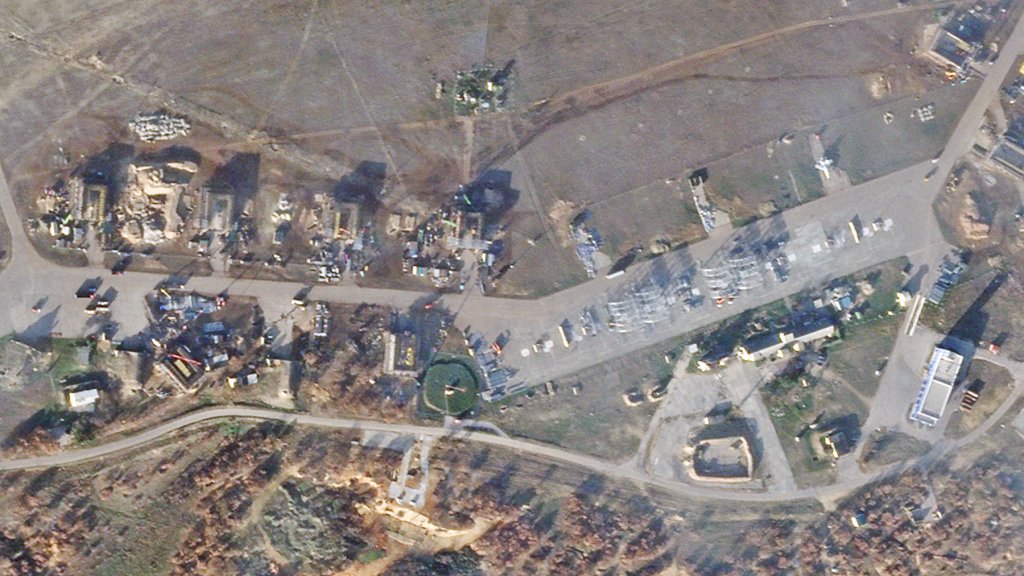

Ukrainian attacks on Russian airbases using drones and U.S.-supplied Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) short-range ballistic missiles with cluster warheads have helped drive this reality home. In turn, Russia has launched its own new push to build hardened and other shelters at various air bases, especially those close to Ukraine.

In addition, “passive defenses” include “not only hardening, but also redundancy measures, prepositioning of supplies, reconstitution capabilities, and camouflage, concealment, and deception measures,” the new report notes. Furthermore, while “passive defenses may seem at odds with a predominantly expeditionary U.S. approach to warfare … unless U.S. forces can defend airfields at home and abroad, they will be unable to support US and allied interests in a conflict.”

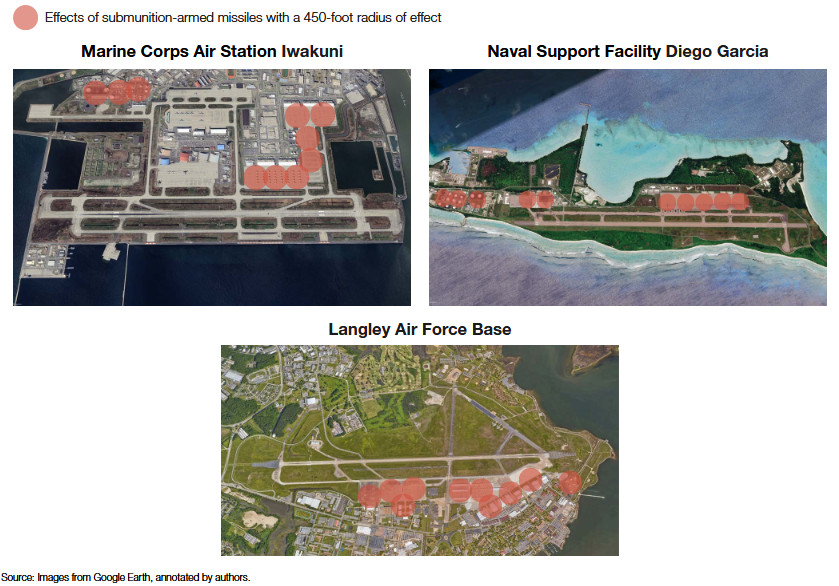

As illustrated below, Hudson’s report assesses that it could take just 10 missiles with warheads capable of scattering cluster munitions across an area with a 450-foot diameter to neutralize all exposed aircraft on the ground and fuel storage at key airbases like Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni in Japan, Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, or Langley Air Force Base in Virginia.

The report also highlights the ever-growing threat posed by drones, and how uncrewed systems and missiles could threaten airbases within the continental United States, as well as overseas. For years now, TWZ has been sounding the alarm on these issues, especially when it comes to the dangers of increasingly more capable drones that are steadily proliferating globally, and noting the continued lag on the part of the U.S. military in addressing them. “Recent Air Force requests for information about ‘enclosures to defend F-15Es from drone attacks’ at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base and F-22 jets at Langley Air Force Base suggest the Air Force is starting to consider the threat more seriously,” Hudson’s report notes, directly citing some of TWZ‘s past reporting. “However, it is again pursuing low-cost solutions (such as canvassing existing open-air shelters or applying nets), which counter-measures such as shaped charges can easily overcome, rather [than] building proper HASs.”

Still unexplained drone incursions over Langley that continued for several weeks in December 2023, which TWZ was first to report, became a particular watershed moment for the discourse around drone threats, including to domestic U.S. military bases. Drone incursions over bases hosting U.S. forces in Europe last year, as well as widespread drone sightings over New Jersey and elsewhere in the United States that have increasingly tended toward hysteria, have further reinforced the reality about the potential threats in the public consciousness.

The issue of hardening and limited investments in new HASs and other passive defenses in the past 20 years, also extends to U.S. allies and partners in the Western Pacific, the report points out. South Korea, which faces the immediate prospect of potential attacks from North Korea, is the notable outlier. Earlier this month, the Japanese Ministry of Defense announced plans to start moving 14 key command centers underground to better shield them, especially from potential Chinese attacks in the event of a larger conflict over Taiwan, as part of its proposed budget for the 2025 Fiscal Year.

As already noted, the report from Hudson stresses that HASs and other infrastructure improvements are not a ‘silver bullet’ solution. It also includes two other recommended lines of effort centered on a potential conflict with China in the Pacific.

The report also calls for increasing the ability of U.S. forces to similarly hold Chinese bases and other critical infrastructure, including facilities deep inside the country, at risk. That, among other things, will require increasing the production and stockpiling of strike munitions, and the development of types that are cheaper and easier to produce at scale. This has long been its own hot-button issue for the U.S. military and is only more so now amid planning for a potential high-end fight with China.

Improving the U.S. military’s ability to project air power from far-flung locations, and without the need for long runways or runways at all, or simply to have aircraft capable of longer-range operations from bases that are less vulnerable to start with, is the other recommended course of action in the report. TWZ has been increasingly highlighting the potential value of crewed and uncrewed aircraft with greater, if not total runway independence, as well as new concepts in aerial refueling, in future major conflicts, especially across the broad expanses of the Pacific.

How the U.S. Air Force and the rest of the U.S. military might actually proceed, especially when it comes to base infrastructure, remains to be seen. Last month, the Air Force notably released a new base modernization strategy that included a focus area on increased resiliency and that pointedly said that the service’s facilities “can no longer be considered a sanctuary.” However, it did not explicitly mention HASs or similar passive defensive measures, last month. Air Force officials have also pushed back on the value of more extensive physical hardening in the past.

“I’m not a big fan of hardening infrastructure,” Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach, then head of Pacific Air Forces, the top Air Force command for that region, said at a roundtable at the 2023 Air and Space Forces Association symposium. “The reason is because of the advent of precision-guided weapons … you saw what we did to the Iraqi Air Force and their hardened aircraft shelters. They’re not so hard when you put a 2,000-pound bomb right through the roof.”

Hudson’s report includes an entire section rebutting arguments like Wilsbach’s, including highlighting how physical hardening would force the PLA to expend more and better weapons in attacks on airbases to try to ensure success. The report also highlights how other countries beyond China, including Russia, North Korea, and Israel, are also very actively investing in new hardened airbase infrastructure.

There are various policy and other hurdles to improving active air and missile defenses around airbases and other critical facilities abroad and at home. This includes the fact that the U.S. Army is currently the lead service responsible for performing that mission at Air Force bases. Top Air Force officials have said they are open to taking on that responsibility as long as it comes with commensurate additional funding.

Lengthy traditional contracting processes and concerns about future U.S. defense budgets, together with competing priorities, present additional issues. The Air Force has been increasingly warning about the affordability of various new advanced aircraft and other modernization efforts, including plans for a new sixth-generation stealth combat jet, Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) drones, and new stealthy tankers, for months now.

“To comprehensively harden airfields, the DoD [Department of Defense] will need to shift from treating each construction project individually to conducting a campaign of construction,” Hudson’s report says. “When facing similar challenges in the past, the DoD addressed them, building 373 HASs in Vietnam over a three-year period and roughly 1,000 HASs in Europe in the 1980s. With decisive action, the DoD can address this problem.”

In the meantime, while the debate in the United States about the value of HASs and other physical defenses continues, China is vastly outpacing the U.S. military in this regard and other countries are also taking note.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com