A unique Cold War-era combat jet bowed out of service in Europe today, with the official retirement of the Italian Air Force’s AMX attack jet, a diminutive strike and reconnaissance specialist that was developed jointly by Italy and Brazil. With the steady switchover to larger, higher-performance, multirole fighters, the AMX was something of an anachronism in its final years of service, but it will nonetheless be remembered for its reliable and highly active service, including successive combat operations in the Balkans, Afghanistan, Libya, and Iraq.

The Italian Air Force (or Aeronautica Militare) marked the formal retirement of its AMX fleet today, at the airbase of Istrana, in northern Italy. Here, the final operator of the aircraft had been the 132° Gruppo (132nd Squadron) of the resident 51º Stormo (51st Wing). According to tradition, the wing prepared a specially painted AMX to celebrate the occasion.

The AMX — known under the Italian military Mission Design Series as the A-11, and named Ghibli, after the North African wind — first entered Italian Air Force service on April 19, 1989, with the service’s test and evaluation unit.

At that time, NATO air forces continued to operate relatively spartan, robust ground-attack aircraft to complement their more expensive and sophisticated fighters and strike aircraft. Other examples included the Anglo-French Jaguar, Franco-German Alpha Jet, the Italo-German Fiat G.91, and the U.S.-made F-5. Before long, however, this class of aircraft would more or less disappear from NATO’s ranks.

For Italy, the AMX began to take shape around the early 1970s, when the Air Force began to plan for a successor to its fleets of F-104G and G.91 fighter-bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. By the 1980s, these aircraft would not only be aging out but also increasingly vulnerable to advances in Warsaw Pact air defenses.

Already at this time, Italy was involved in the Panavia Tornado program, which would provide an advanced, supersonic strike and reconnaissance aircraft tailored to survive the advances in air defenses of the 1980s.

But the Tornado was a very high-end solution to the problem and the Italian Air Force also needed a cheaper and less sophisticated aircraft for close air support (CAS) and battlefield air interdiction, as well as reconnaissance, including in less-contested airspace, as well as to ensure overall fleet numbers.

In 1973, the Italian Air Force prepared a document that looked at possible solutions to meet the requirement. The state-owned Aeritalia company and the privately owned Aermacchi began to offer a variety of design concepts, with consideration also being given to whether a common basic airframe could fulfill close air support and training requirements.

An official requirement was issued in 1977, under the name Caccia Bombardiere Ricognitore 80 (CBR 80, or fighter-bomber and reconnaissance for the 1980s).

Compared to the Tornado, the requirement called for one-third of the weapons load and half of the operating costs. It would also be simpler to manufacture and cheap enough to be acquired in large numbers. While a Tornado cost around $40 million in the mid-1980s, an AMX was priced at approximately $13 million.

The new aircraft was to have a single engine, high subsonic (Mach 0.85) performance, and capable navigation and attack avionics. It was also expected to operate from short airstrips (less than 3,000 feet), including unimproved ones, and to deliver a 5,000-pound payload on a target 200 nautical miles from its base after a hi-lo-hi attack profile.

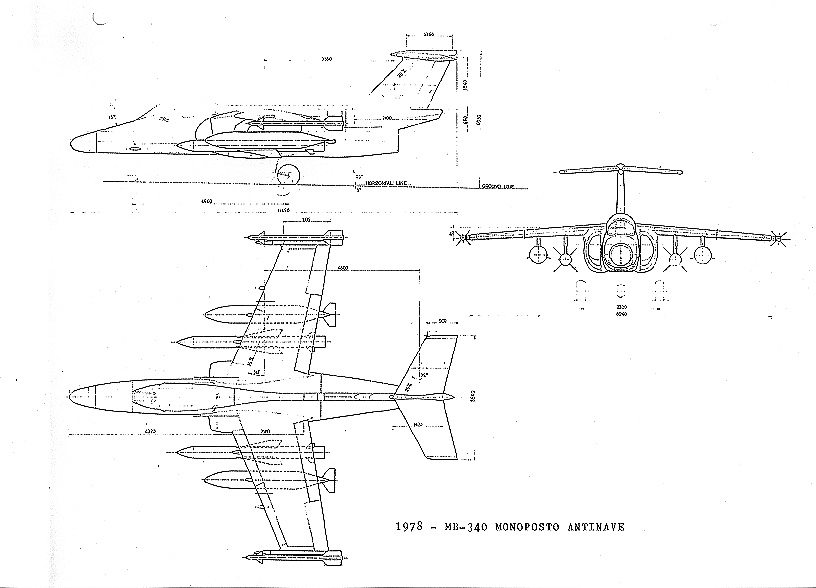

With Aeritalia offering its 3-20/10 design and Aermacchi the rival MB.340, Italy decided to get both companies involved in the program, which would be now known as AMX (Aeronautica Militare Experimental). Initially, Aeritalia had a 70 percent stake in the work, with Aermacchi taking the remaining 30 percent. The chosen engine was the non-afterburning Rolls-Royce RB.168 Spey Mk 807, license-built by FiatAvio.

Italy had begun to seek a foreign partner to share the costs of the program in the definition phase, with Sweden emerging as a possible candidate. Ultimately, Sweden chose to develop its own multirole Gripen, but a partner for the AMX did appear in the shape of Brazil, which was seeking a replacement for its veteran Douglas B-26 Invader CAS and counterinsurgency aircraft, withdrawn from use in 1975.

This led to Embraer’s A-X program, which proposed a single-seat, jet-powered fighter-bomber much like the Italian CBR 80. Ultimately, in 1980, Italy and Brazil decided to join forces on what was now the AMX program. The development effort kicked off with plans to build six flying prototypes, four Italian and two Brazilian.

Under a bilateral agreement, AMX production aircraft would be built for Italy by Aeritalia and Aermacchi, while Brazil’s examples would be produced locally by Embraer. Work and project costs were divided as 46.5 percent for Aeritalia, 23.8 percent for Aermacchi, and 29.7 percent for Embraer.

The first prototype built at Aeritalia’s Turin facility and took off for the first time on May 15, 1984. Two years later, the AMX International consortium was created to promote export sales of the aircraft, but, despite widespread interest, these never materialized. The AMX arrived too late on the scene to make the promised impact. As well as defense cuts at end of the Cold War, the aircraft faced competition from cheaper turboprop light-attack aircraft and adapted jet trainers, as well as secondhand aircraft, notably the F-5.

In total, Italy bought 110 single-seat A-11As and 26 two-seat TA-11As, a reduction compared to the original plans that envisaged 187 A-11As and 51 TA-11As. The first Italian production aircraft took to the air in May 1988 and was accepted by the Air Force in December of the same year. Brazil, meanwhile, received 56 production aircraft.

In September 1990, the first AMX was delivered to the Italian Air Force’s initial frontline squadron, the 103° Gruppo of the 51° Stormo, at Istrana, for operational conversion before working toward initial operational capability. Subsequent deliveries went to the 2° Stormo at Rivolto, the 3° Stormo at Villafranca, and the 32° Stormo at Amendola.

The demise of the Warsaw Pact threat saw the Italian Air Force begin to decommission AMX units in the mid-1990s, but at the same time, new contingencies saw the aircraft pressed into combat duty, initially over the Balkans. Starting in 1995, the AMX was involved in Operation Deny Flight, enforcing a no-fly zone. The AMX flew reconnaissance sorties, the latter with the pod-based Orpheus system. The type’s first combat missions were flown over the former Yugoslavia under Operation Allied Force in 1999. Here, the standard armament included 500-pound Mk 82 freefall bombs as well as the Israeli Elbit Opher with imaging infrared guidance.

The experiences of the Balkans, and the changing face of air combat in the 21st century, saw the Italian AMX pass through a midlife upgrade, known as Aggiornamento Capacità Operative e Logistiche (ACOL, or Upgrade of Operational and Logistic Capabilities).

In all, 42 A-11As and 10 TA-11As underwent the ACOL program starting in 2005. This added new cockpit displays, compatibility with night-vision goggles, inertial/GPS navigation, an upgraded electronic warfare system, and the addition of the Rafael RecceLite and Litening III pods, for reconnaissance and targeting. New weapons included the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) and Elbit Lizard II and GBU-16 laser-guided bomb.

The upgraded jets were known as the A-11B and TA-11B and the program was completed in 2012.

The next operational assignment for the AMX was in Afghanistan, where A-11Bs first arrived in 2009, rotating into theater to replace Italian Tornados in support of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). As well as reconnaissance missions, the AMX aircraft also flew CAS sorties, using laser-guided bombs as well as the internal 20mm M61A1 Vulcan rotary cannon.

The AMX remained active in Afghanistan until 2014, flying more than 3,000 sorties and almost 10,000 flight hours, with only four jets deployed at any given time.

Alongside Afghanistan, the Italian Air Force deployed the AMX during Operation Unified Protector over Libya in 2011, with four A-11Bs flying CAS and reconnaissance missions.

By this stage, the AMX appeared to be in the twilight of its Italian Air Force career, but the advance of ISIS in the Middle East soon saw the aircraft back in action as part of Operation Inherent Resolve between 2016 and 2019. The Italian contribution included the “Black Cats” Task Group at Ahmad al-Jaber Air Base in Kuwait. The missions that followed were reconnaissance only, the jets using the RecceLite pods to photograph more than 17,000 targets during around 1,500 sorties and 6,000 flight hours.

By this time, the rapid pace of development in NATO air arms was also being reflected in changes in the Italian Air Force. In 2013, the 13° Gruppo decommissioned its AMXs and then began transition to the new F-35A stealth fighter, marking a quantum leap in capability.

While the AMX looks geriatric in contrast to the F-35, its operational career provides ample evidence of its basic utility and versatility.

The final tally for the AMX with the Italian Air Force includes over 240,000 flight hours across 35 years of service. Of those, around 18,500 hours were recorded in operational environments.

For the kinds of low-intensity air campaigns that defined air combat for well over two decades after the end of the Cold War, the subsonic AMX’s rugged simplicity and ease of operation made it well up to the task.

Outside of Europe, meanwhile, there is still a place for this kind of robust, low-cost CAS and counterinsurgency specialist. Brazil, for example, has used the AMX extensively for counter-narcotics work in the Amazon, where its ability to operate from improvised airstrips has been a huge benefit. Other operators looking for aircraft to fulfill the same kinds of missions typically now look toward cost-efficient turboprop platforms or light combat aircraft derived from existing jet trainers, like the FA-50 Golden Eagle family.

With that in mind, the retirement of Italy’s last AMX attack jets closes out an important chapter for that air force, but also arguably concludes an epoch within NATO, too, with the end of the line for Cold War-era robust ground-attack aircraft.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com