The U.S. Army has laid out plans to significantly expand its air and missile defense units, with a particular focus on counter-drone and counter-cruise missile capabilities, as part of a larger restructuring of its forces. This reflects U.S. military concerns about these and other aerial threats that have been growing for years now. This is also a major turn-around for the service, which has been very much playing catch-up with these threats, as The War Zone has highlighted in the past.

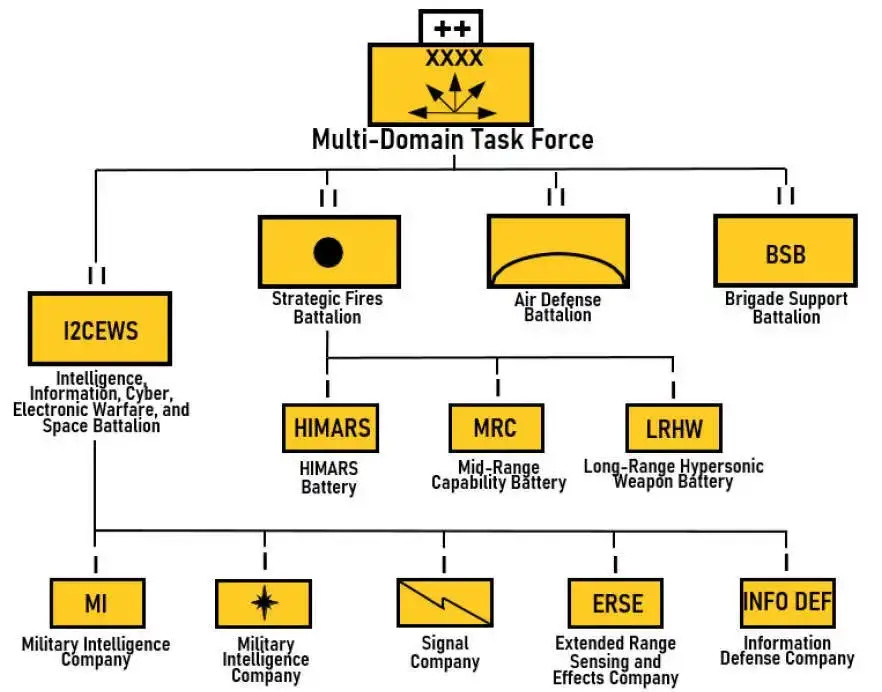

The Army released a white paper earlier today that details various force structure changes it plans to implement between now and the end of the decade. The force structure transformation includes completing the standing up of five Multi-Domain Task Forces (MDTFs). These task forces will include air and missile defense units, as well as ones equipped with new long-range missile systems, including hypersonic types. They will also have new electronic and cyber warfare systems and other advanced capabilities. Additional air and missile defense units separate from the MDTFs are set to be established.

“Bringing these and other capabilities into the Army requires adding roughly 7,500 more authorizations for soldiers in high priority formations,” according to the white paper. “Given the addition of 7,500 new authorizations needed to bring new capabilities in the force, the Army needed to identify some 32,000 authorizations across the rest of the force that could be phased out.”

So, special operations forces, cavalry, and certain other units will be downsized as part of the new force structure plan. In all, the Army expects what it calls its “authorized” force size, which refers to the total number of personnel that would be required to 100-percent staff its existing units, to drop from 494,000 to 470,000. By law, the Army’s current actual active-duty end strength is set at 445,000 personnel and the service has had trouble meeting its recruitment goals in recent years. The active duty totals also do not include additional forces assigned to the Army Reserve and the Army National Guard.

“For nearly twenty years, the Army’s force structure reflected a focus on counterinsurgency and counterterrorism operations that dominated after the 9/11 attacks. The Army will continue to need capabilities related to these missions,” the Army’s white paper on its force transformation plans explains. “But in light of the changing security environment and evolving character of war, the Army is refocusing on conducting large-scale combat operations against technologically advanced military powers. To meet these requirements, the Army must generate new capabilities and re-balance its force structure.”

The white paper makes clear that new air and missile defenses are absolutely central to these plans. Each of the five MDTFs will include what is currently being called an “indirect fire protection capability (IFPC) battalion.” In addition, the service wants to stand up four more independent IFPC battalions. The Army has defined this unit’s core mission as “providing a short to medium-range capability to defend against unmanned aerial systems, cruise missiles, rockets, artillery and mortars.”

Though not explicitly mentioned in the Army’s overview of its new force structure plans, the IFPC battalion’s primary weapon is expected to be the Enduring Shield. The service has said in the past that a typical Enduring Shield platoon, of which multiple would be assigned to each IFPC battalion, consists of four launchers linked to at least one AN/MPQ-64 Sentinel-series radar using the Army’s Integrated Battle Command System (IBCS) network.

The Enduring Shield launchers are palletized and have been designed from the start to be able to fire multiple types of surface-to-air munitions. The system is set to be initially fielded with AIM-9X Sidewinder short-range heat-seeking missiles as its primary effector, but the Army is already pursuing another interceptor more optimized for shooting down incoming subsonic and supersonic cruise missiles.

Since the AIM-9X is a short-range missile, it is unclear what will provide the medium-range capability the Army says the IFPC battalions will have. There have been discussions in the past about significantly expanding the AIM-9X’s range performance. The second interceptor for the system could have extended range compared to the Sidewinder, as well.

The Army has notably been without any medium-range air defense capability available for general use since its retirement of the Hawk surface-to-air missile system in the 1990s. The service does have a small number of medium-range National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (NASAMS), but these are exclusively deployed to protect Washington, D.C., and the greater National Capital Region.

The Army’s new force structure plans also call for the creation of nine “counter-small UAS (C-sUAS) batteries” that will be attached to the IFPC battalions and existing division-level air defense battalions. It’s unknown at this time how these batteries will be equipped, but this all follows the service’s announcement of plans to significantly expand its inventory of Coyote anti-drone interceptors, and mobile and fixed launchers for them, in the next five years, as you can read more about here.

The Army, and the rest of the U.S. military, are also actively exploring a variety of other systems designed to help tackle lower-tier drones, including man-portable and vehicle-mounted electronic warfare jammers and laser and high-power microwave-directed energy weapons.

Lastly, the Army’s force structure white paper outlines plans to stand up four more Maneuver Short Range Air Defense (M-SHORAD) battalions to help “counter low altitude aerial threats, including UAS, rotary wing aircraft, and fixed-wing aircraft.” The Army already has two M-SHORAD battalions and is in the process of establishing a third.

The main air defense assigned to the existing M-SHORAD battalions is a mobile platform based on the 8×8 Stryker armored vehicle that has a turret armed with Stinger short-range heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles. Each one also has a 30mm automatic cannon capable of firing proximity-fuzed ammunition that is ideally suited for knocking down drones. These units are also set to get Stryker-based vehicles with laser-directed energy weapons, and potentially ones with high-power microwaves, as well.

The Army is also seeking a replacement for the venerable Stinger that will be compatible with existing launchers for those missiles, such as the ones on the Stryker M-SHORAD vehicles. There is the possibility that the service could acquire M-SHORAD systems using other vehicles beyond the Stryker, such as its new tracked Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicles (AMPV).

The white paper on the new Army force transformation plans notably does not talk about expanding the service’s long-range air and missile defense capacity, to include Patriot and Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) systems. It does say that the specific details it contains “are only a representative sample of the Army’s full capability growth.” The service has said it is working to establish at least one additional Patriot battalion.

The War Zone has previously highlighted the worryingly small number of Army Patriot units in light of current and potential future operational demands both overseas and domestically. The planned new lower-tier air defense units could help alleviate some of the pressure on the Patriot force.

Altogether, the focus on new air and missile defense capacity in the Army’s new force structure plans makes perfect sense. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine and the crisis in and around the Red Sea have brought into sharp relief the scale and scope of threats posed by drones and cruise missiles, as well as ballistic missiles. The situation in the Red Sea, as well as a recent surge of attacks on U.S. forces on land across the Middle East, has further underscored the steady proliferation of increasingly more capable drones and missiles not just to smaller national armed forces, but also to non-state actors.

In any future large-scale conflict, such as one in the Pacific against China, U.S. forces would expect to see very large volumes of incoming missiles and drones across broad areas.

At the same time, concerns about these aerial threats, especially when it comes to drones, are not new, nor is the knowledge that their scale has been expanding in recent years, as The War Zone has repeatedly highlighted. The drone threat looks to be on the cusp of entering an entirely new phase thanks in large part to artificial intelligence-enabled hardware and software.

“I’ve been in the Army for 38 years, and in my entire time in the Army on battlefields in Iraq, in Afghanistan, Syria, I never had to look up,” now-retired Army Gen. Richard Clarke, then head of U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM), put it very succinctly while speaking at the annual Aspen Security Forum in 2022. “I never had to look up because the U.S. always maintained air superiority and our forces were protected because we had air cover. But now with everything from quadcopters – they’re very small – up to very large unmanned aerial vehicles [UAV], we won’t always have that luxury.”

“The cost of entry into this, particularly for some of the small unmanned aerial systems, is very, very low,” Clarke added at that time.

So, the fact that the Army has just now announced new plans for significant expansions in air and missile defense capacity to come in the next five years or so shows that the service is still very much trying to catch up with threats that exist now. This also points to challenges the service continues to face in growing these forces and their associated capabilities. The Army has notably faced significant challenges in the past just enticing soldiers to join air defense units, something that has been compounded by the demands placed on this relatively small segment of the service.

“Many times, soldiers go for six months and get extended to nine months,” Lt. Gen. Daniel Karbler, head of U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command, said at the 2023 Space and Missile Defense Symposium, according to Defense News. “Many times, they deploy for nine months and extend to 12 months [and] sometimes they think they’re going for a year to get extended … into 15 months.”

In addition, U.S. forces across the board, not just dedicated anti-drone units, will increasingly require defenses against uncrewed aircraft. The War Zone recently highlighted this reality in a feature centered on how hard-kill active protection systems (APS) could help provide tanks and other armored vehicles with additional layers of protection against these threats.

Altogether, it remains to be seen how the Army will actually proceed with its plans to boost its air and missile defense capacity in the coming years, as well as the rest of the newly announced force structure changes. What is clear is that the service already has a need for significantly more units to defend against aerial threats, especially drones and cruise missiles.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com