The 25mm automatic cannon nestled inside the F-35A variant of the Joint Strike Fighter is now deemed to be an effective weapon. For years, a host of issues had left these stealth fighters unable to shoot straight. Problems with the 25mm cannon have also been a particularly notable talking point in the still-controversial debate over plans to supplant the venerable A-10 Warthog ground attack jet with the F-35A.

Russ Goemaere, a spokesperson for the F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO), provided The War Zone with an update on the F-35A’s gun, which is formally designated the GAU-22/A, earlier this week. In the U.S. military, the F-35A is operated exclusively by the U.S. Air Force.

“After working with the Air Force and our industry partners we can report that the gun has been improved and is effective,” Goemaere said in a statement. “We continue to work with industry, the Services, and our international partners for further improvements and to maximize effectiveness and lethality at the tactical/operational level.”

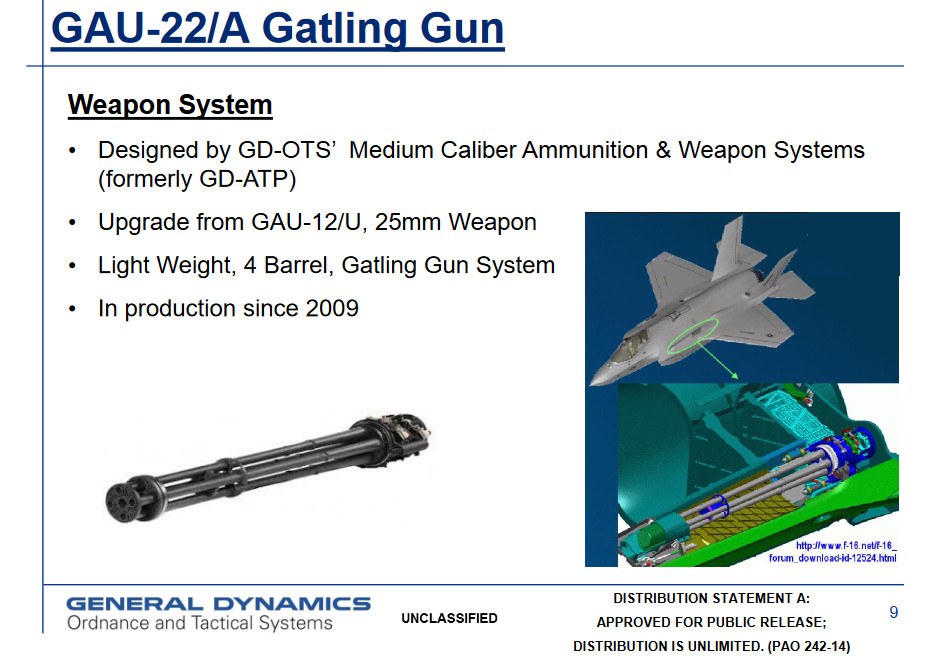

Each F-35A has a single GAU-22/A, which is a four-barreled Gatling cannon with a rate of fire of 3,300 rounds per minute, installed on an internal mount above the aircraft’s left engine intake. To maintain the jet’s stealthy characteristics, the gun’s muzzle is hidden behind a flush-mounted door that opens when the weapon is fired and closes back up when it stops.

The GAU-22/A is a lighter-weight derivative of the five-barreled GAU-12/U found on the AV-8B Harrier jump jet and the now-retired AC-130U Spooky gunship. It is interesting to note that all other tactical jets currently in U.S. military service, except for the A-10 and the aforementioned Harrier, are armed with versions of the 20mm M61 Vulcan cannon, a six-barreled Galting-type design.

As installed on the F-35A, the GAU-22/A feeds from a magazine with a maximum capacity of 180 rounds. Given the size of the magazine, the gun has just over three seconds worth of total available firing time during a single sortie.

The short and vertical takeoff and landing-capable F-35B and carrier-based F-35C variants of the Joint Strike Fighter, which the U.S. Marine Corps and Navy operate, do not have internal guns. These versions can be armed with a GPU-9/A gun pod, which contains a GAU-22/A and 220 rounds of 25mm ammunition, loaded on their centerline stations.

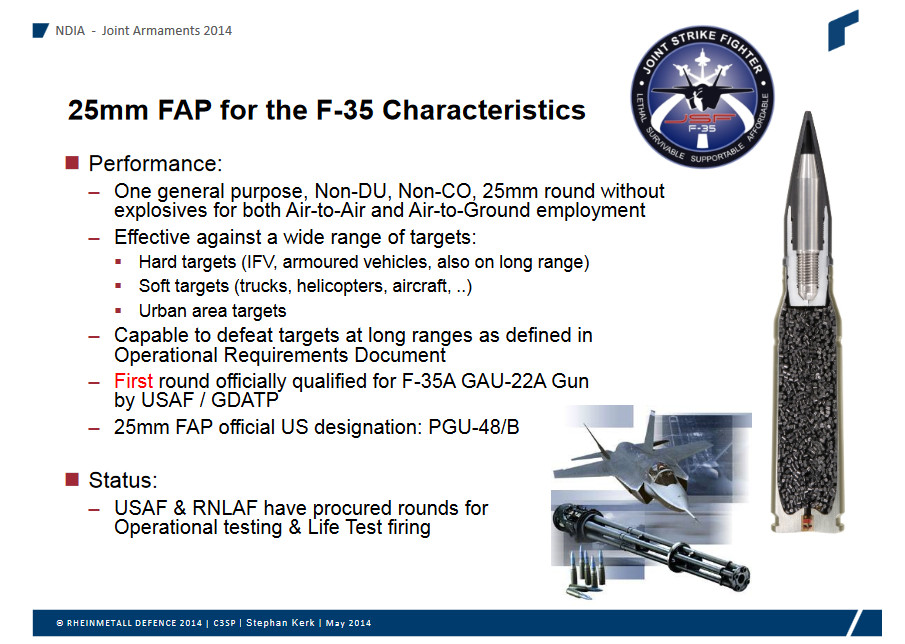

The current standard operational round for the GAU-22/A is the PGU-48/B, a so-called Frangible Armor Piercing (FAP) round with a tungsten core. This is a kinetic round designed to destroy targets through sheer force of impact. The frangible penetrator is designed to break up and turn into a hail of deadly shrapnel after penetration, as well.

German defense contractor Rheinmetall, which manufactures the PGU-48/B, has touted the round as being particularly well-suited to engaging enemy aircraft and armored vehicles on the ground in the past. The rounds are also expensive, costing around $131 each, according to the U.S. Air Force’s latest budget request for the 2025 Fiscal Year. At that unit price, it costs $23,580 to fully load an F-35A’s magazine.

For comparison, the Air Force’s current standard 20mm PGU-28A/B semi-armor-piercing high-explosive incendiary cartridges each cost about $34. So, the price tag to fill up the 511-round magazine for the M61 Vulcan cannon on an F-16C Viper, the primary aircraft the F-35A is intended to supplant, is only around $17,000.

There is always the possibility that other types of 25mm ammunition, such as high explosive and/or incendiary types, including ones already developed for use in the GAU-12/U, could be cleared for use in the GAU-22/A. What limitations there might be in making use of existing and future ammunition types beyond the PGU-48/B are unclear.

Though the internal guns were installed on production F-35As from the start, the first real ability to use them operationally came with the introduction of the Block 3F software package starting in the mid-2010s. Testing in 2016 uncovered an initial set of issues impacting the F-35A with its internal gun and F-35B/Cs with podded ones. The problems were linked to how certain symbology was displayed to pilots through their helmet-mounted displays (HMD). Unlike many combat jets past and present, all three F-35 variants lack a traditional heads-up display (HUD) in the cockpit and instead project the same kinds of information, and much more, directly onto the visor of the pilot’s helmet.

“Both DT [developmental test] and OT [operational test] pilots have reported concerns from preliminary test flights that the air-to-ground gun strafing symbology, displayed in the helmet, is currently operationally unusable and potentially unsafe to complete the planned testing due to a combination of symbol clutter obscuring the target, difficulty reading key information, and pipper stability,” according to a report the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E) published in 2017. “Also, for air-to-air employment, the pipper symbology is very unstable while tracking a target aircraft; however, the funnel version of the air-to-air gunsight appears to be more stable in early testing.”

“Fixing these deficiencies may require changes to the mission systems software that controls symbology to the helmet, or the radar software, even though the program recently released the final planned version of flight test software, Block 3FR6,” the DOT&E’s report released in 2017 added.

The Air Force had declared that it had reached initial operational capability (IOC) with the F-35A in 2016.

By 2020, changes had been made to the software packages on F-35s to help fix the symbology problems, though DOT&E said more testing was needed to reach a definitive assessment. Issues with employing the podded guns also seemed to have been resolved. However, by that time, additional problems specific to the internal GAU-22/A installation on the F-35A had emerged.

“Investigations into the gun mounts of the F-35A revealed misalignments that result in muzzle alignment errors. As a result, the true alignment of each F-35A gun is not known, so the program is considering options to re-boresight and correct gun alignments,” another DOT&E report, published in 2020, said. “Based on F-35A gun testing to date, DOT&E considers the accuracy of the gun, as installed in the F-35A, to be unacceptable.”

On top of that, the misalignment of the gun was causing physical damage to F-35As while firing.

“Units flying newer F-35A aircraft discovered cracks in the outer mold-line coatings and the underlying chine longeron skin, near the gun muzzle, after aircraft returned from flights when the gun was employed,” the report DOT&E released in 2020 explained. “Due to the recent cracking near the gun muzzle in newer F-35A aircraft, the U.S. Air Force has restricted the gun to combat use only for production Lot 9 and newer aircraft.”

Exactly when these issues were addressed to the point that the F-35 Joint Program Office determined that the gun was finally “effective” is not entirely clear. Cracking issues relating to the use of the F-35A’s internal gun have also resurfaced in recent years, but do not look to be impacting the weapon’s accuracy.

“Two aircraft experienced cracking in the blast panel in front of the gun. The program is conducting recurring visual inspections following each gunfire event to ensure that the cracks are not spreading and the panel is still safely in place,” the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a Congressional watchdog, noted in a report in 2022. “The F-35 program has replaced the panel with a newer panel that has larger fastener holes as an interim fix. Blast panels are being repaired on an as-needed basis. Aircraft acquired under lot 10, those delivered in 2018, and later incorporate the redesigned panel in production. Fleet retrofit is pending funding.”

“Originally observed on earlier delivered aircraft, some newer aircraft are again experiencing blast skin cracking on the redesigned area next to the F-35A internal gun. This cracking is a result of higher than designed for pressure conditions when firing the gun. The program observed these cracks on Lot 13 aircraft and it expects the issue to affect Lot 14 and Lot 15 aircraft due to similar designs,” GAO said in another report published last year. “There is risk that undetected crack growth could result in part of the panel breaking off, with material potentially going into the engine; however, the program has not identified any foreign object debris among the panels that have had issues. The program is managing the risk by post-flight inspections of the panel after gun use and by replacement of cracked panels by contractor field teams.”

The War Zone has reached back out to the F-35 JPO for an update on efforts to mitigate and/or resolve this issue.

Since the issues with the F-35A’s gun first emerged, they have been major talking points in the debate about the ability of these stealth jets to effectively replace the Air Force’s A-10s. In 2022, DOT&E completed a final report on comparison testing of the F-35A and the A-10C that had been conducted between 2018 and 2019, which included mention of a need to “fix the F-35A gun.” We only know this thanks to a heavily redacted copy of the report that the independent non-profit Project on Government Oversight (POGO) obtained via the Freedom of Information Act and published publicly last year. So, the full context of that gun-related recommendation remains unknown. This comparison testing was highly controversial from the start and DOT&E’s report was effectively buried.

Even under optimal conditions, the F-35A GAU-22/A with its 180 rounds is in no way directly comparable firepower-wise to what is offered by the A-10C’s legendarily massive 30mm GAU-8/A Avenger cannon and its 1,174-round magazine. But close air support is far more about precision-guided munitions employment than strafing these days. Still, it is an important tool to have available when the circumstances require it. It’s worth pointing out that the Avenger also created a host of serious headaches during the development and initial fielding of the Warthog, as you can learn more about in this past War Zone feature.

The Air Force’s position has long been that the ability of the F-35A, as well as other aircraft, to take over close air support duties from the A-10 lies more with an increasing focus on the use of precision-guided bombs and missiles, as well as Warthog’s vulnerability to modern air defenses. The A-10’s advocates contend that the aircraft remains uniquely suited to performing close air support and other often overlooked missions, and that various steps could be readily taken to mitigate various operational limitations. You can read more about all of this in the context of the additional information from the redacted comparison testing report here.

Questions certainly remain about the overall utility of the F-35A’s gun, with its just over three seconds of total firing time, in an air-to-ground or air-to-air context. In an air-to-ground scenario, especially, the 25mm PGU-48/B round presents its additional limitations in terms of what effects the gun can generate compared to ones that have the option of firing high explosive and/or incendiary ammunition, regardless of accuracy. Still, the 25mm rounds, even if limited in quantity, are far more destructive against air and ground targets than the more plentiful 20mm ones of a similar type found in all other American fighter aircraft.

In air-to-air combat, Air Force F-35As are expected to use their stealthy design and other advanced capabilities to avoid having to engage in close-range dogfights where an internal gun could come into play. That being said, in a future conflict, especially a high-end one, there could be an unavoidable potential for these kinds of aerial engagements even if they would still be uncommon.

Altogether, after years of significant problems, the F-35A’s gun now at least works to some relevant degree and gives pilots flying F-35As the option to ‘switch to guns’ against targets in the air or on the ground.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com