While the future of the U.S. Air Force’s F-15E Strike Eagle fleet has been under some scrutiny recently, there’s little doubt that the jet remains the service’s ‘go-to’ platform for complex air-to-ground scenarios in demanding environments, testified by its regular appearances in global hotspots and participation in high-profile missions. What’s less well known is the aircraft’s potent capabilities in the air-to-air realm, something that is now being built upon by the Air Force’s new F-15EX Eagle II. TWZ talked to Lt. Col. (retired) Daren “Shotgun” Sorenson who, with almost 3,000 hours in the F-15E, is well placed to provide insight on flying and fighting in the jet in the air-to-air domain.

As the name suggests, the F-15E Strike Eagle was developed very much with the air-to-ground mission in mind, but it’s also always had a powerful air-to-air capability. How has that capability developed over time?

Obviously, the F-15E came from the F-15C and D world, but it was born in an air-to-ground role — that was the original mission. When I started flying it, you could definitely tell that was the focus and a lot of the aircrew that were originally trained and then flew operationally in the model came from an air-to-ground background.

My first assignment was in England, so we had a lot of F-111 guys some F-4 guys, but all had that air-to-ground background. That obviously played a heavy influence on how we trained, the tactics, and the focus. It wasn’t so much what the jet could or couldn’t do, it was what the Air Force wanted it to do, and how they wanted us to train. The vast majority of our time — probably 80 percent — was spent just training different air-to-ground roles. So that was definitely prevalent.

But then what we saw over the course of my career was that that focus started to migrate, and the mission started to grow. And we started to pull a lot of rotations into the [Iraqi] no-fly zones. Our role in the no-fly zone was air-to-air, it was defensive counter-air, DCA. We would relieve F-15C units that were in theater so they could have a break and so obviously we had to train for that. Training to fill that Northern Watch/Southern Watch mission over Iraq required us to train more air-to-air. When we would do spin-ups, before the deployment, we would all of a sudden start doing that, probably at least on a 50:50 basis with our air-to-ground training. And that’s when I think people started to get more comfortable with it. The folks at the mid-level of leadership started to realize, ‘Hey, this jet’s fully capable.’

Presumably, though, the F-15E is always going to have certain disadvantages in this mission compared to the air-to-air-optimized F-15C?

You know, we weren’t really handicapped at all in what the jet was able to do, especially beyond visual range. At the time, the AN/APG-70 was awesome and fully capable of doing air-to-air intercepts, including long-range targeting, utilizing the AMRAAM. Obviously, [the radar] has only gotten better since then.

All those kinds of things were pretty much on par with what the C model was able to do. As we would go out and train and do these air-to-air missions, folks realized that it really didn’t matter which type of F-15 was being used. It really didn’t matter until you got into the post-merge type of BFM [basic fighter maneuvers] fight, then obviously the C-model has got an advantage. It’s got lighter weight, less drag, and turns very well. You would definitely see an advantage post-merge but, you know, how likely is that kind of fight?

Once F-15Es started taking on more dedicated air defense types of mission, how did that change things within the Strike Eagle community, and the wider Air Force?

The commanders started to realize that, with the proper amount of training, we could fully jump in and fill a CAP [combat air patrol] that any C-model was doing in the theater. And so that’s how they started to use us. Whether it’s the dog chasing its tail or not, that mission started to drive our training. And then it just started to evolve from there.

We started to get more air-to-air type pilots into the jet; we started to get people who transferred from the C-model into the E-model. That was awesome because they brought all that experience into the community. Instructors and even patch-wearers who graduated from the Weapons School, would come in and really be able to grow the squadron and the entire wing, the whole community, up to higher levels of skill, because they brought all that knowledge with them. These guys had done it for a couple of thousand hours and then it just started to kind of grow from there. We would get to the point where you could then ‘plug and play.’

And these evolving tactics were presumably also being refined in large-force exercises, too?

One of my last assignments when I was on active duty was teaching and instructing at Red Flag. We would have units come in and they’re like, ‘Hey, we need a four-ship to do OCA [offensive counter-air] and escort and to do all these other air-to-air missions.’ We would run out of dedicated air-to-air platforms, we would never have enough F-22s, we would never have enough C-models and so we would just plug in the E-model squadrons where we needed them, and they would come in and it was transparent.

The air-to-air F-15Es would flow with the whole package, they would do the mission. Their performance was more based on the individual aircrew training and how prepared they were for that mission. It wasn’t a restriction or a reflection on the jet at all. So that put us in a really good place because that meant that the jet ended up being way more capable than I think it was ever designed to be when they initially made the E-model.

Clearly, there are discrete air-to-air and air-to-ground missions, but you’re not always doing either one or the other, right? To what degree can you swing from one to the other in the F-15E, fighting your way in fighting your way out?

That’s been kind of the core, the bread and butter, of the F-15E since day one. One of my earliest memories of training in the E-model was surface-to-air tactics opposed by Red Air. So that’s kind of the general assumption. In the E-model, it goes all the way back to Desert Storm. But obviously, the essential tactics date back earlier.

We were making our money in low-level ingress on TFR [terrain-following radar] with NVGs [night-vision goggles]. In fact, we even predated NVGs, we just had the NAVFLIR so you’re just running in at low level at night, only looking through the FLIR in the HUD [head-up display], but you’re outstripping the OCA’s ability or even desire to escort you in. So you’re going to go in low, probably trying to sneak in underneath some kind of air defense system, and not tip your hand.

The whole theory was we were going to carry a limited number of air-to-air missiles, at the time, probably a combination of AIM-7s or AIM-120s, a couple of AIM-9s, or whatever we had at the time. And then use them kind of as a last resort.

How simple is it for you, as the pilot, to ‘swing’ from one mission type to another?

There is a lot of multitasking, but the jet can seamlessly switch between modes. You’re not having to flip a lot of switches, there’s literally one HOTAS [hands on throttle and stick] switch to go from air-to-air to air-to-ground, and everything in the jet switches as necessary. But I never lose the ability to fire missiles or target or drop bombs.

We would practice opposed target areas where you’re targeting an air-to-air bandit who’s defending the target area. You may have to maneuver and then swing back in for the air-to-ground attack and then immediately reengage air-to-air targets as you come off target. All that can be done super easy with the jet the way it’s made.

At this point, we need to address one of the really big differences in the F-15E, compared with the F-15C, and other frontline Air Force fighters. What kind of advantage does two crewmembers provide when it comes to air-to-air combat, specifically?

The division of labor actually works out really well in that case. Depending on your altitude, the pilot is always pretty much running the radar in an air-to-air mode, while the WSO [weapons system officer] in the back is basically focused on navigation and the target attack and delivering the air-to-ground munitions. That really works out well, especially if you’re flying at low altitude at night.

When it comes to crew duties, that’s when you really understand why two is better than one. The WSO can literally be lasing in a Paveway II munition while I’m shooting an AIM-120 AMRAAM or AIM-9 at an air-to-air target. I mean, the air-to-ground weapon hasn’t even impacted yet and I can already be engaging back in an air-to-air mentality. We train to that. Now, whether it ever happened, history can relate to that. But that’s kind of our worst-case scenario, just making that assumption that we’re not always going to have embedded OCA escort.

The luxury of assuming we have C-models or F-22s or anybody else with us is just one that we either don’t want because of the specific tactics or simply can’t have, based on what’s available in the AOR [area of responsibility], especially when there’s only so much gas to go around. We have the luxury of being able to carry a lot of gas and being able to go really far so we can use that to our advantage.

You mention being assigned a target, or targets on the ground, but having to fight your way in and out, without defensive escorts, as a worst-case scenario. How close did you come to flying a mission like that?

Personally, we ran into this on the first night of Operation Iraqi Freedom. We were tasked with dropping bombs in downtown Baghdad on night one of OIF back in 2003. There was no OCA — they were literally consumed with doing dedicated escort to the bombers, and everyone else that was fragged to go in over Baghdad that night.

We were basically on our own and we were at medium altitude. That, to us, was just basic ‘Strike Eagle 101’ tactics but we were flying right next to Al Taqaddum and other MiG-29 bases. And there was absolutely nobody in between us and them. We were watching them on NVGs and if they had been able to launch MiG-29s that were on alert, there was nothing else around to defend us. We’d have to roll in and shoot them, probably while we had [air-to-ground] weapons in flight. This is probably the closest that I can come to thinking of how that would play out in the real world.

Everyone knows who studied OIF, at some point, they ended up just sending the C-models home. They were like ‘Hey, we don’t have any work for you.’ At that point, we were maybe the only assets in theater that could do as good a job at air-to-air, as far as being able to do OCA or DCA and being able to escort bombers. We trained for all that.

Can you maybe explain a little more about how the pilot and WSO work together as a team in an air-to-air scenario, something that is pretty much unique to the F-15E (and soon the F-15EX) in the Air Force right now?

Normally the pilot will still run the radar and then the WSO can focus on other sensors. He can be watching and utilizing things like the datalink. You still have a targeting pod so you have a bunch of other sensors on board that he can use to absorb information and then communicate that to raise SA [situational awareness]. The radar is just one of several systems that require input, at least on the F-15.

What I found in the E-model, as the pilot you want to focus on the radar and its returns and what it’s telling you about the targeting information and maintain primary control of that. Then you just monitor the other systems for good information that the WSO can then start manipulating.

You know, it’s a little like your iPhone. You can take the datalink screen — we call it the SIT — and you can change the scope. You can zoom in, you can zoom out, you can compare other information, you can filter and fuse data in and out, so you can change what it’s displaying to help you out in an air-to-air fight. And there are ways to make it show you this 360-degree holistic picture.

For example, if you’re running in hot towards a target, you want to have it zoomed out so that you see the whole picture in front of you. You want to know where each group of bandits are. You know that the radar may be providing information, or you may be getting something from off-board on the datalink. But you want to be able to see the entire picture and you’re still looking at these fairly small scopes in the jet, so you want to have it sized properly so you can absorb what it’s telling you. But then if you go cold and the picture now is on your six you want to change that presentation. You now want the picture and the information on what’s behind instead of what’s in front of you. All that just requires little HOTAS inputs, but if you’re flying a jet, you know you’re a little busy. If it’s already set up for you and it’s already configured, then boom. It just makes you that much quicker to process information and makes you that much more effective.

When you divide those duties with a WSO, things are just done that much faster. I don’t have to do them. When you’re crewed with somebody that you get along well with, it’s like being in a good marriage. You can finish each other’s sentences. I don’t have to say anything — he already knows what I want, he’s anticipating what I need. To see those two people gel is really, really beneficial in a combat scenario.

With the F-35, the level of sensor fusion means that huge amounts of data can be presented to a single pilot in a manageable way. Even with the two-seat F-15EX, the Air Force plans on operating these jets with a single pilot at least some of the time. Is there an argument that the days of two-crew fighters are over?

When you really look at the art and the complexity of real-world missions, that’s when you really start to see the value of the two crew. It’s very underrated, especially in the single-seat community. Yes, they train a lot of different missions. But what you’ll see often is they’ll go out with a dedicated mindset of ‘Hey, today we’re only doing air-to-air.’ If they do need to switch role, that’s an overwhelming number of tasks to ask a single person to do, especially in a high-threat environment if you’re engaged by SAMs [surface-to-air missiles] and air-to-air as well. Now you’re trying to employ both air-to-ground and air-to-air weapons. Obviously some of the newer weapons are launch-and-forget type of things. And that’s all fine, but it’s still an extreme level of tasks that a pilot has to be trained to be current and proficient in, to be able to execute well, and that’s really hard to do with any one person.

The people who can do that well are the cream of the crop. They are the instructors, multiple thousands of hours, the Weapons School graduates, the people who have been fortunate enough to be able to spend a lot of time in those Red Flag scenarios or in real-world combat. You can’t just do this overnight; you can’t really expect a brand-new young wingman to perform at that level, that takes years and years of training, and thousands of hours of experience to really get good at it.

That’s another thing that’s extremely undervalued — just how difficult it is mentally. Because on top of all that you still have to fly the jet. You’re pulling Gs and you’re going fast, and you may be at low altitude and maybe at night and in bad weather. There are just thousands of things that are going on and it’s one of the highest workloads that I can imagine. Being able to share that burden with another person in a jet is gold. It’s really gold and the people who understand that have probably had to live it in one way, shape, or form. I think the pilots that see that in real-time, whether it’s in the formation or in the package, the guys next to you, they start to appreciate what you’re able to offer.

I flew one time in a D-model with the F-15C squadron at Lakenheath during my tour there and just the amount of information I was able to help the pilot with was incredible. Keeping a tally or keeping a visual of his flight lead, while we were doing ACM [air combat maneuvering]. He was like, ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you,’ because it just increased his SA during this ACM fight. I think he finally started to get it, that four eyeballs are better than two when you take all the other ego things out of it. The value added in any kind of combat is precious.

I talked to a friend of mine once who told me they were flying the two-seat F-16 versions every single day in Iraq and putting an extra pilot in the back seat because they wanted the additional eyeballs looking out for SAM launches. And I’m like, ‘Well, that’s very interesting. You don’t read about that in the news.’ But that’s what they were doing in the real world. The folks that have been there kind of get it, they get it how valuable that extra person is.

Well, you have a highly capable radar, datalink, plus another set of eyes, but the F-15E also has various other podded sensors. Do you use them for air-to-air combat too?

You utilize everything the best that you can. Obviously, the pod was born to track and illuminate targets on the ground. But if you have the right environmental conditions and it can provide additional information for you, then that’s another sensor that the WSO may be trying to utilize. You take advantage of everything that you can.

Remember, too, that nothing works all the time, which is something that generates a lot of discussions, especially in air-to-air. You can’t always say that your radar is going to work perfectly all the time. There are a lot of things that could happen to cause that to not be 100 percent, whether it’s jamming or other things that are causing issues. The same is true with the datalink and the target pod. You go out and you know what it’s capable of, but you have to see what it’s going to provide you on that given day.

There’s also the seeker on the AIM-9X. A lot of times we would come up with well-thought-out combat loads with a mix of AIM-9M ‘Mikes’ and AIM-9X. The chances are I’m going to shoot the 9-Mikes first, and I’ll keep the AIM-9X and use it as a last resort, but then it still gives me all the onboard cueing capability, just hanging there on the rail, which is itself a great sensor. I can use that even if I don’t shoot it.

How about the Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing System (JHMCS)? Would both crew members be wearing that?

For me, that depended on which of the jets were modified. At the time that I retired, they had basically modified all the front seats of the jets and they were in the process of starting to migrate the rear cockpits. Now, I would probably assume that everyone would be wearing JHMCS, which just adds even more information and capability to the aircraft.

Overall, JHMCS was a fantastic addition. When I think of the major upgrades that we got, while I was flying the aircraft, the first thing was NVGs. Adding NVGs was absolutely a game-changer for our night capabilities. And then probably the next major thing would be the datalink and then the JHMCS at the end.

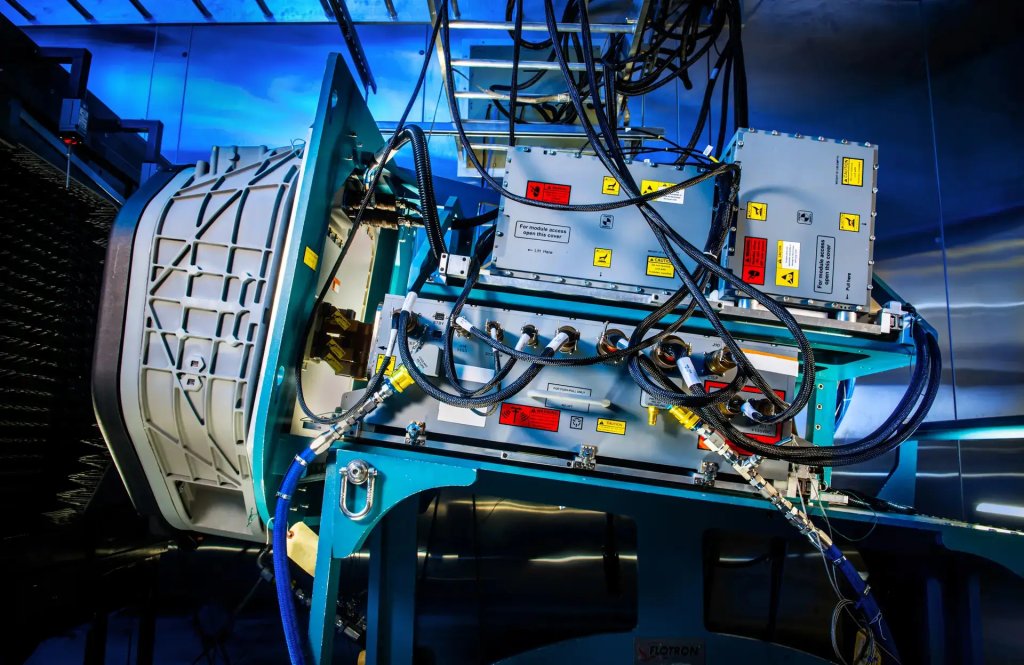

Did you get to fly with the new AN/APG-82 active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar before you retired?

The new radar was in test at the 422nd Test and Evaluation Squadron at Nellis so there were definitely some guys flying with it. Operationally, I don’t think anyone got it before I retired. But I did get to fly a couple of sorties with it to see what it was capable of. And yeah, it’s absolutely fantastic. That’s another thing that folks don’t realize, just how high of a quality of a radar that is, it’s really on par with the best that’s out there.

So you have air-to-air and air-to-ground missions, plus a diverse range of sensors and a rapid pace of modernization across the fleet. How do you keep on top of the training demands?

It’s virtually impossible to be good at everything all the time. That is the biggest limiting factor when you talk about the capability of the aircraft. It’s about looking at the next deployment, and the expectation of what we have to be good at, and that’s going to be the focus of our training. Your skill level varies with your proficiency and so there’s no way that you can fly enough to be good at everything that the jet can do. It’s just too much. It’s really too much.

You have to have a focus and that focus becomes ‘what’s your next deployment,’ and hopefully, we know that several months out to prepare, so that every aircrew in that unit can get ready.

And then we go, and we have good results and we come home, and we make it look easy. That’s the goal, but you don’t see the endless hours of hard work, sometimes seven days a week that these guys are putting in. My average workday was 14 hours a day, probably about six days a week. That’s really tough.

When you were training for air-to-air, what dissimilar non-U.S. types did you come up against?

I got to dogfight MiG-29s and countless Typhoons. When I was at Lakenheath, we flew against everybody in Europe, it was so fun. That was a dream come true. I didn’t know it could be that good. As a young wingman at my first squadron, I just thought that was normal. You know, we’d go out and do the Mach Loop, and then you’d fight anybody else that was out there. It was really, really unique and you don’t realize how awesome how those opportunities are until you come back to the United States, and then fighting anything dissimilar becomes 100 times harder, just because of how spread out the assets are and how busy everyone is. In Europe, we would routinely go over to France and other places on the continent and fly with just about everybody that was over there. On any given day, it was really great training.

And that would include taking the F-15E into within-visual-range setups, too?

Yeah. I spent two weeks with the French Air Force fighting and training with their Mirage 2000s. We would do dedicated trips where we would go and spend a couple of weeks. I spent two weeks in Africa flying with Tunisian F-5s. All BFM, everything within visual range, and some ACM, but all they had was AIM-9Ps. So, we all were just trained to go up against that, and a gun, and we would go and do this all the time. The ability to grow and see new things is amazing training for aircrews because you very quickly reach a plateau if all you have to fight and train against are other F-15s.

What was it like flying against F-16s in the F-15E?

I flew BFM with Dutch F-16s at Lakenheath. First, you have to figure out how you’re going to do BFM with F-16s. There are things that you can try, and you may be successful, or you may not. That’s where the art comes in. And a lot of people don’t understand that when they just look at it from afar — they don’t understand the art of dogfighting.

When you’re fighting, you realize that the jet is a tool, but the person fighting is the pilot, and more times than not the pilot in the cockpit is the game changer. You can put a Weapon School graduate in an F-15E against an average F-16 pilot and I’ll bet on the patch-wearer every single time because the experience that that guy has will probably outweigh the advantage that the jet has.

More times than not I was successful against F-16s. The more you learn the more you understand how to maximize your jet and exploit any weaknesses in that aircraft. And for one, everyone knew at the time that the F-16 had an AOA [angle of attack] limiter that wouldn’t let the jet pull more than a certain AOA. This meant that if you got into a slow-speed fight, no matter how hard the pilot pulled back on the stick, the jet would override him. We didn’t have that limitation so I could fly my aircraft at a higher AOA/slower airspeed, and I could win a slow-speed fight with an F-16. I just had to get him into that position. I can now maneuver my aircraft, slower than him hopefully, get behind him, and then start to get the advantage. There were little secrets like that.

A lot of times, you’d be surprised to hear, people have a hard time seeing the F-15E against a desert background, or in certain mountains and stuff like that. I can get to the merge with an advantage, some people might say ‘Oh that’s cheating.’ Well, nothing’s cheating in combat, right?

When it comes to performance in the air-to-air arena, how big a factor are the different engines in the F-15E?

Some jets still have the older -220 engines, some have the newer -229, and the motor difference is an absolute game changer. In fact, it can cause whoever you’re fighting, if they don’t know the difference, a lot of embarrassment, because that amount of additional thrust almost negates the drag and the weight penalty of the CFTs [conformal fuel tanks]. I’ve flown the E-model without CFTs, but no, we don’t do flying training with them in that configuration.*

When we were fighting in England, all the jets had -229 motors, and so we were able to fight much more on par with the C-models, because we had all that additional thrust.

Sometimes we would even get the different E-models together with the different motors, just so the guys could see it first-hand. I was fortunate enough to get a lot of time in both and also got to travel to different bases. I would get to fly them frequently, and you just kind of cringe when you’re flying the -220 motors, because it just takes significantly longer, just on basic tasks like takeoff, climbing out, flying on a hot day.

You can reach a point where you are thrust-limited with the -220 motors. If you’re carrying a full air-to-ground load of weapons, full tanks of gas, external bags, and you’re trying to climb up and go somewhere high and fast, on a hot day, the motors will be like, ‘Oh, this is all you’re getting today.’

On the other hand, the -229s are really hard to max out, you can load that jet down with whatever combat loads you want, fill it up full of gas, and it’s still going to go, and it’ll go as high as you want and as fast as you want, and it’s like, ‘Oh yeah, this is how that jet was meant to be.’ I’ve been to 50,000 feet in this jet, and it does it with no problem — that the flexibility that you need. It’s definitely an important consideration when you’re planning these things, and it even comes across at the operational level when we’re planning things at the AOC [Air Operations Center], you have to understand what jets are on the ATO. You have to understand because you may ask them to do something that they may struggle to do with to do which could impact your overall plan.

If we have a Red Flag in the summertime, you’ll see the impact of those different motors. And to me, bigger is always better. You can’t have enough thrust, because you translate it into energy, and then that’s life.

* The Air Force is now conducting operational deployments using F-15Es with their CFTs removed, for example when Lakenheath-based Strike Eagles conducted deterrence operations at Łask Air Base, Poland, in 2022, as part of a scheduled aircraft rotation in support of the U.S. forward fighter presence along NATO’s eastern flank. You can read more about this combat-credible no-CFT F-15E configuration here. According to the Air Force, the configuration is designed to increase the Strike Eagle’s air dominance capabilities by “enabling supercruise capability, maximizing offensive flow, and enhancing survivability within and beyond visual range with a full combat loadout.”

Few will have predicted that, when the F-15E began to be delivered to the Air Force in 1988, it would be swatting down scores of Iranian drones in defense of Israel, 36 years later. How well-suited is the Strike Eagle to this task?

It’s easy work. You can do it all day long until you run out of missiles. But the better tactic is to destroy the sites before they launch. The most difficult part is where to place the CAPs so the jets are in a good place to defend the assets they’re trying to protect.

The drone war is kind of like a video game. You just gotta get the jets up in the air and position them correctly for an intercept. The radar will easily see them after they’re launched and then it’s just how many missiles you have versus how many drones are launched. The technical aspect of detecting them and downing them is easy. The bigger challenge is, I’m sure, all sorts of rules of engagement (ROE) they must comply with before being authorized to shoot.

Let’s finish up with your thoughts on the F-15EX.

It’s no surprise to me that they’re still building, and people are still buying the F-15. I think that thing’s been in production my entire life, which is a pretty strong statement, especially for a fighter. One, the aircraft is extremely well built, and then its capability continues to grow over the years, it hasn’t been a static platform at all, and the EX is a good example of that, it continues to be relevant.

One discussion is, ‘Well, it’s not stealth. Why buy when it’s not stealth?’ Well, there’s a lot of air capability requirements and missions where you don’t need stealth. And we train through those in Red Flag and other scenarios where you just need aircraft in the air, you need radars, you need missiles, and you need gas, and you need aircrew that are trained on how to do this well and that. Stealth just isn’t in that realm. Stealth is great when you have to penetrate into a target area and survive and then get home. But for a lot of those needs, that’s not a huge requirement.

We will never be able to fight a war with just F-22s because we just don’t have enough of them. They have to come back, they have to refuel, they have to rearm, they have to land, they have to get turned, they have to take off again. And in so many scenarios, you need numbers, you need mass. There’s this huge, underappreciated value of being able to just stay in a CAP [combat air patrol] for three hours and not run out of gas. And then when the shooting war starts, the guys who run out of missiles first normally lose. And you look at the new EX and you say, ‘Wow, look at how many missiles that aircraft can carry. Look at how much gas it can carry and look how long it can stay in the fight.’

There are so many challenges that you can find yourself in where this aircraft becomes the perfect filler. If we force mix, I don’t have to have a wall of F-22s to win this fight. I may only need one or two F-22s, and I can fill the rest of it with six F-15s with a ton of missiles.

I kind of drool watching the new EX come off the assembly line and then get delivered. I’m just in envy of those guys who get to fly a brand-new EX model — it sounds absolutely fantastic.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com