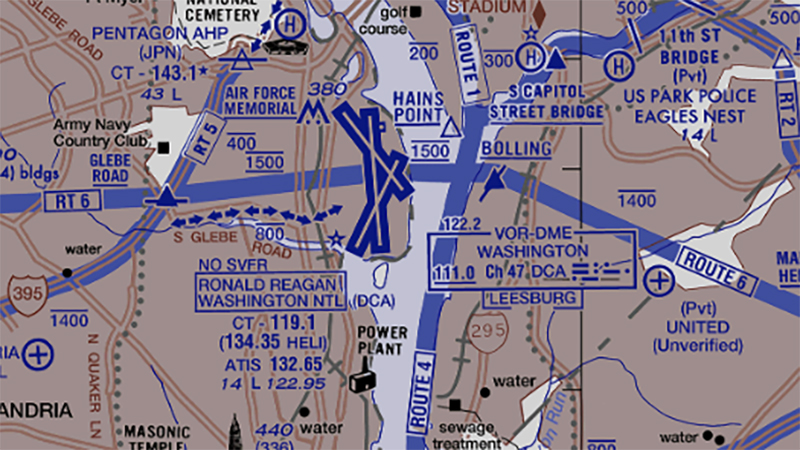

The skies over Washington D.C., where an Army Black Hawk helicopter collided with a passenger airliner Wednesday night, killing 67, is the most tightly controlled and surveilled airspace open to civilian air traffic in the United States. As such, it can be a hazardous place to be airborne, particularly at night, when bedrock principles of good airmanship can fall by the wayside and helicopter and air traffic control personnel can get overwhelmed, current and former military helicopter pilots told TWZ Thursday.

The collision killed the three soldiers aboard the UH-60 helicopter, as well as 64 aboard the PSA Airlines Bombardier CRJ700 regional jet, which was on its final approach to Ronald Reagan National Airport shortly before 9 p.m. when the accident occurred over the Potomac River.

It happened as the inbound airliner from Wichita, Kansas, made its visual approach to Reagan’s Runway 33. The PSA flight was operating as Flight 5342 for American Airlines. Go here to read our ongoing coverage of the tragedy.

Multiple investigations have been launched into the incident. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, echoing President Donald Trump, said Thursday that “there was some sort of elevation issue” with the Fort Belvoir, Virginia, based Black Hawk that the Army was investigating.

Beyond that, it remains anybody’s guess as to how a mishap of this magnitude could have happened. But helicopter pilots who spoke with TWZ shared their thoughts on what would have complicated the sky over the Potomac Wednesday night.

The jet was close to landing at Reagan, and therefore, “to be a couple hundred feet above the Potomac there is not unusual,” said Dr. Michael Canders, a retired Air Force and Navy helicopter pilot who has also worked as a commercial airline pilot and has flown over the capital both in and out of uniform.

“You’ve got helicopters operating along the Potomac River, and I think the [height restriction] is 200 feet,” Canders, now an aviation professor at Farmingdale College in New York State, told TWZ Thursday. “When they are in the vicinity of the airport, they have to be especially vigilant. It’s not that unusual for this combination of traffic to occur.”

As such, awareness of other aircraft is key, he said, and helicopter pilots should always be aware of airliners on such a northwest heading for runway 33. Officials have yet to say what altitude the helicopter and passenger jet were at when they collided.

“If you’re going to fly past, make sure you remain clear and under it, so you don’t impact or interfere with any aircraft,” Canders said.

Jets fly on very specific approaches, and helicopter routes are designed with that in mind, which makes the collision’s causes that much more unclear, Tom Longo, a retired Marine Corps CH-53E pilot who once helped plan President Barack Obama’s helicopter flights as part of Marine Helicopter Squadron One, told TWZ.

“[Helicopter] routes were designed to go under jets,” Longo said. “There’s deconfliction built into this, if you stay on the route and do what you’re supposed to.”

“The glide slope going into the airport for the airplane shouldn’t intercept the helicopter route,” he added, likening such flights to highway travel.

“You’re going 55 mph, someone else is going 55 mph in the other direction, but if you stay on the highway, it’s not that hard,” Longo said. “It’s not that hard until you start freelancing.”

While not inclined to speculate on the mishap’s cause, Canders said the helicopter crew may have not followed a basic pilot mantra.

“It’s called ‘see and avoid,’” he said, “and it’s as simple as it sounds.”

See and avoid basically entails making sure that a pilot maintains visual situational awareness of the skies around their aircraft, precisely to avoid the type of collision that happened Wednesday.

“Were there factors that contributed to maybe an inability to see and avoid? That’s what the investigators will try to determine,” he added. “That’s the key question, why wasn’t see and avoid complied with?”

Despite modern technology, flying at night remains “significantly” harder than day flying, Canders said.

“Both of them are hard to see [at night] because the only thing you’re going to typically see are some lights,” Canders said. “You’ll see what they call the position lights and anti-collision lights, but when they’re interfered with, or when they’re among the ground lighting, it’s not always easy to pick out how far away they are, how fast they’re going, so that’s the challenge of night flying. It’s really a different kind of world.”

Air traffic control can help, as can instruments in the cockpit, but “you’ve got to be looking outside the aircraft,” Canders said, adding that cockpit display advancements have led to a trend of relying on such systems, “maybe more than you should.” Such systems include TCAS in airliners and the Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) in a helicopter’s cockpit display. Earlier Thursday, TWZ laid out what TCAS can and cannot do.

“But there’s a little bit of lag on that technology, on those electronics,” he said. “So back to looking outside, you’re definitely going to be able to determine, am I on a collision course with that, although it is harder at night and pilots are often drawn inside. They want to look at the display.”

Canders flew a derivative of the Black Hawk used for Air Force rescue missions known as the HH-60G Pave Hawk, and he recalled flying that low-level route over the Potomac.

“It tends to be busy there,” he said. “So it’s back to see and avoid, and always having your head on a swivel, looking outside and making sure that you’re not going to run into another [aircraft].”

Still, Canders said the skies over Washington aren’t any more difficult to fly through than similarly busy skies in New York City or other major metropolitan areas. But staying below 200 feet is critical, or pilots risk losing their licenses.

“If you were flying formation, the last guy in the formation would have to work pretty hard to maintain not exceeding the altitude, and you’d have to bug the guy in the front, like, you got to go lower,” Longo, who retired in 2012, told TWZ. “It wasn’t hard as much as it felt you weren’t used to it. Typically when you fly around the cities, you would fly high, not to bug people. This seemed like you have to do the opposite.”

Meanwhile, some military pilots have noted online that aircraft have so much to track, and can get easily distracted, despite how common it is to have helicopters flying in and around major airports like Reagan.

“You are operating a complex aircraft in a complex environment and you can get task saturated even with a two-pilot crew,” like that aboard the Black Hawk, @Thenewarea51, a career helicopter pilot and friend of the site, wrote on X Thursday. He added that “task saturation also can happen to the most experienced air traffic controller.”

In such circumstances, see and avoid can understandably become harder to execute.

“[Air traffic control] may call out traffic and you confirm that you have it in sight, or maybe you spot the wrong aircraft,” the pilot wrote. “It takes one little thing to happen to lose sight of that traffic in question, e.g., a light flashes on your instrument panel, the person sitting next to you or behind you asks a question, you have multiple radios that you are listening to, you spot a bird, and the list goes on and on.”

To that pilot, pressing questions include whether the Black Hawk pilots were wearing night vision googles (NVG), which provide around a 40-degree field of view. The pilot also wondered if the helicopter identified the correct aircraft and assured the air traffic control that they had it in sight and would maintain visual separation.

“How many other aircraft was the controller trying to keep separated, why didn’t the controller inform the CRJ about the helicopter?” the pilot added. “It’s a mind boggling amount of data to digest even for a pilot or control with thousands of hours of experience.”

Canders noted that, if the Black Hawk’s crew had realized it was in the path of the airliner sooner, it could have taken evasive measures and been out of the jet’s way in about five seconds.

Less than a day after the mishap, Longo is convinced someone made a mistake, but he’s not sure who was ultimately responsible.

“[Was the helicopter] off course? Was the airplane off course?” he asked. “And you can’t do this without talking to the [air traffic control] tower, so the tower would have cleared them through. There’s at least three choices … I’m sure everyone thought that he or she was doing the right thing, but one of the three erred.”

As the saying goes, military regulations are written in blood. New policies are often enacted after older policies lead to loss of life. As the Army, the National Transportation Safety Board and other federal agencies dive into what went wrong Wednesday night, what caused this tragedy remains to be unveiled, as does the question of what could have been done to prevent the loss of those 67 souls.

Email the authors: geoff@twz.com, howard@twz.com