The spy plane at the center of one of the most notorious post-Cold War air incidents, a U.S. Navy EP-3E Aries II, has arrived at the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona, for future public display. The EP-3E’s journey to get to the museum has been a long one, starting with the dramatic collision with a Chinese fighter in the so-called Hainan Island incident in 2001.

EP-3E serial number 156511 was the aircraft involved in the collision. Confirmed by an Instagram post from the Pima Air & Space Museum, it arrived at the location yesterday, having been towed there from the boneyard at the nearby 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG) in Tucson.

The museum states that the Aries II is not yet ready for public display, but it will be a truly unique exhibit once that happens.

Even without the turbulent history of this particular airframe, the EP-3E — one of America’s most sensitive intelligence-gathering assets — is already an impressively rare aircraft to see in the flesh.

A derivative of the P-3 Orion maritime patrol aircraft, the EP-3E has a critical important intelligence-gathering role and is optimized for the maritime/littoral domain. The aircraft is equipped to gather real-time tactical signals intelligence, including intercepting communications and locating and classifying emitters, including those related to integrated air defense systems.

On April 1, 2001, serial number 156511 was flying a routine reconnaissance mission over the South China Sea out of Kadena Air Base, Okinawa, Japan. As well as six flight crew, it carried a reconnaissance crew of 18, from the Navy, Marines, and Air Force. It was assigned to Fleet Air Reconnaissance Squadron One (VQ-1), known as the “World Watchers.”

Tasked with monitoring Chinese communications as well radio-frequency signals emitted by radars and weapon systems, the EP-3E was flying at 22,500 feet off Hong Kong’s coast in international airspace, when the crew was alerted to the fact that interceptors had been launched from Lingshui air base on Hainan Island, China.

Within minutes, a pair of People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) J-8D Finback interceptors appeared about a mile away. This was the signal for the EP-3E crew to turn around from its mission and prepare to head back to base.

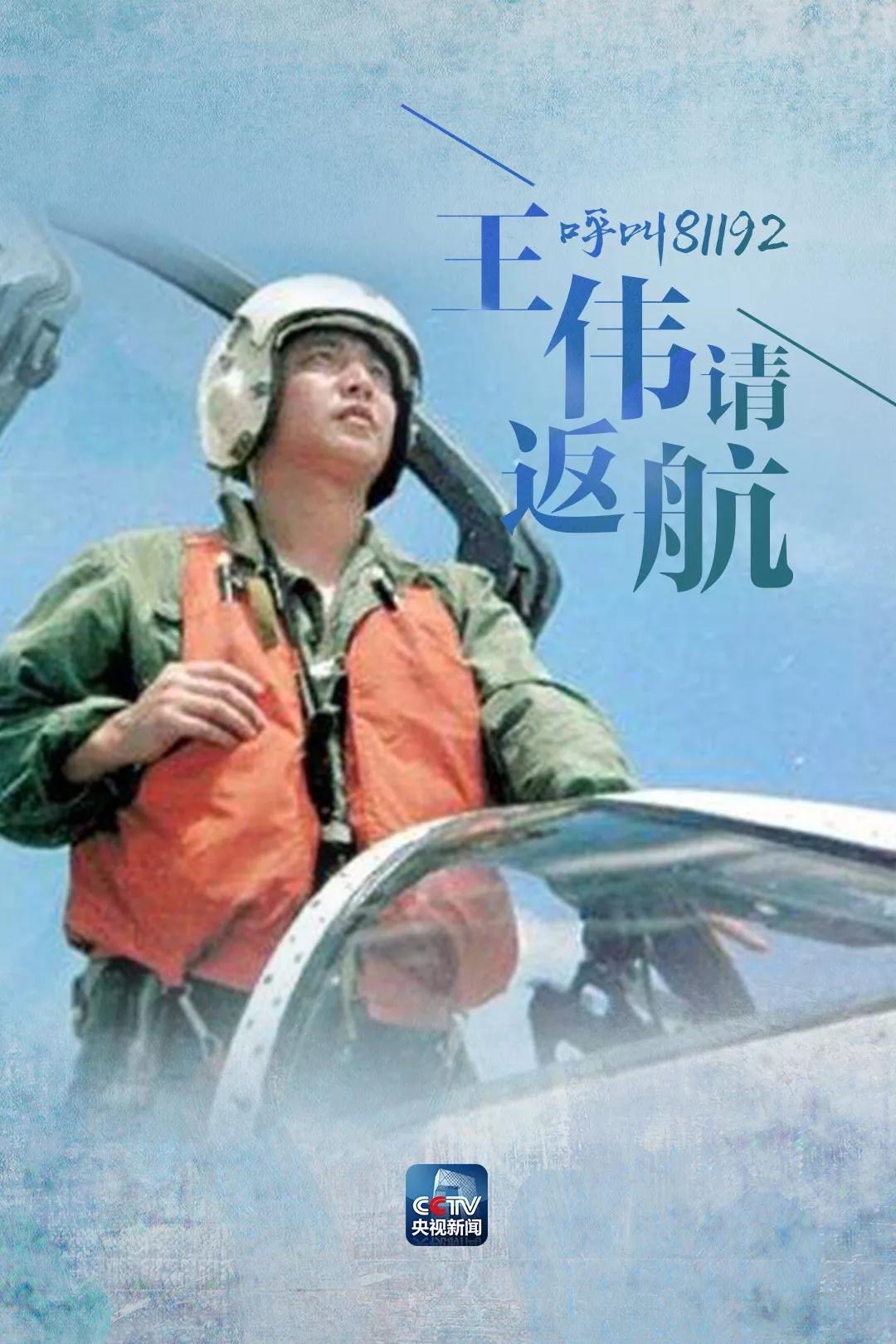

Next, however, one of the J-8s approached from the rear left and took up station just 10 feet away from the EP-3E’s wing. The Chinese pilot, Wang Wei, saluted the American crew, then dropped back 100 feet.

Assigned to the 9th Naval Division, Wei was already well known to U.S. reconnaissance crews, on account of his aggressive approaches to spy planes. This kind of behavior included buzzing at high speed as well as cutting in front of and across the path of the reconnaissance aircraft — also known as a ‘headbutting’ maneuver.

“[Wei] was extra crazy. He would get so close to the plane that you could literally jump from one wingtip to another wingtip,” one of the EP-3E crew members later told The Intercept.

On one previous occasion, Wang had got close enough to show a piece of paper with his email address to the U.S. crew, who were able to photograph it.

Despite complaints made to Beijing, these kinds of intercepts had continued, China claiming it was well within its right to defend what it saw as its sovereign airspace.

On this occasion, Wei approached the EP-3E for a second time, coming within five feet of the spy plane, mouthed something to the crew, and then fell back again.

On his third approach, Wei got too close to the EP-3E. Hit jet was apparently sucked into the slipstream and was sliced in two by one of the propellers. He reportedly ejected but was killed.

As the Chinese fighter was torn in half, debris impacted the EP-3E, cutting through the fuselage and damaging the radome, two of the propellers, and an engine.

The EP-3E rolled inverted as the crew battled with rapid depressurization. It then dropped like a stone some 14,000 feet, vibrating violently the whole time.

The EP-3E pilot, Lt. Shane Osborn, wrestled with the controls and ordered the crew to prepare to bail out. Osborn considered putting the aircraft down in the sea but then reconsidered, deciding on a recovery at Lingshui air base — around 20 minutes away. With no working flaps, the aircraft too heavy, and also falling apart, this seemed like the only option.

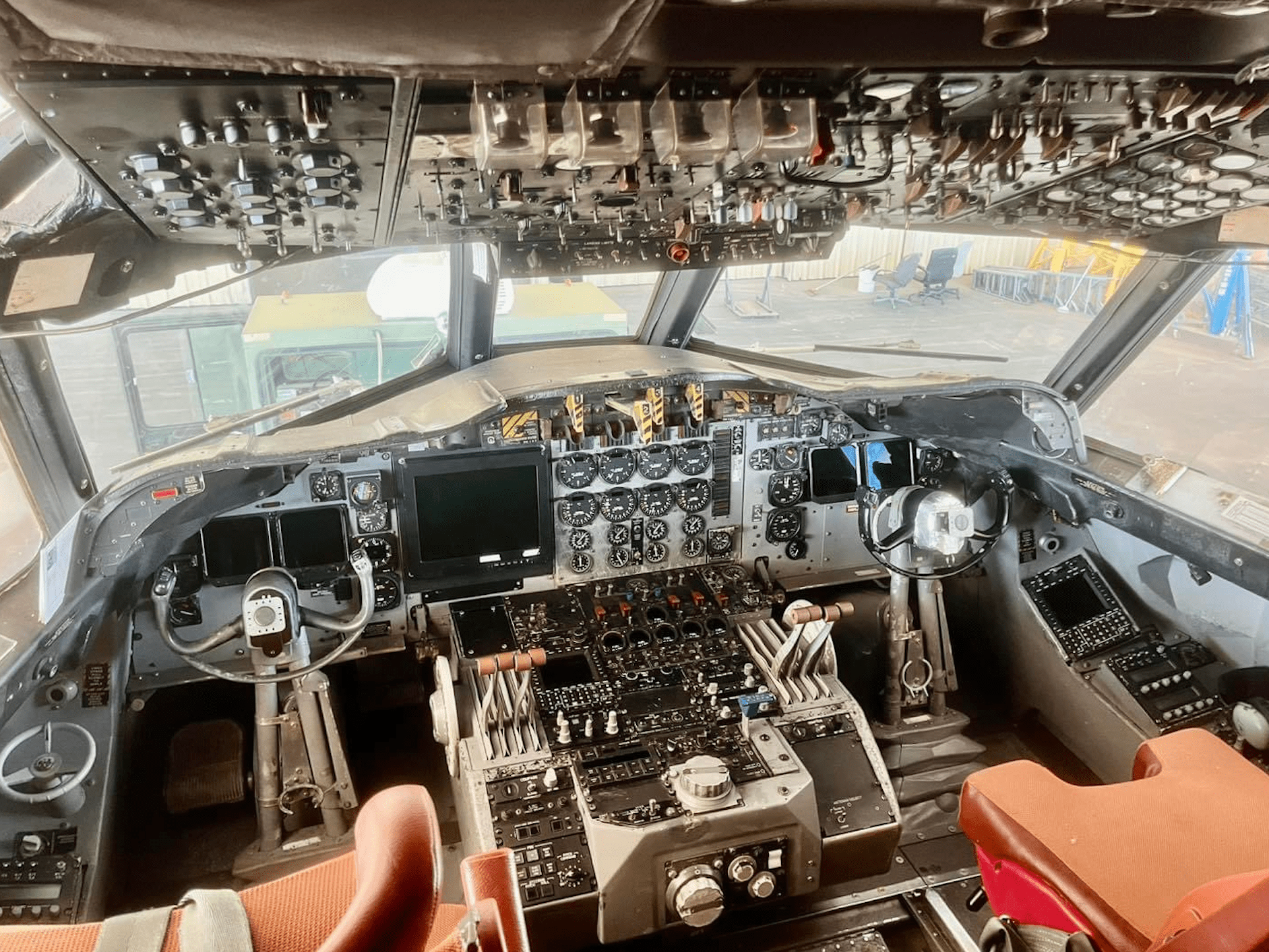

Amid the chaos, the crew made frantic attempts to destroy as much of the highly sensitive equipment and materials on board the spy plane as they could.

Unfortunately, only one member of the crew had ever taken part in an inflight emergency destruction drill, so there was little understanding as to what needed to be done to keep secrets out of Chinese hands.

An emergency ax was available but proved to be too blunt to do real damage to equipment and there was no shredder, so documents had to be torn up by hand. Cassette tapes full of intercepted data were unspooled by hand.

“I was bashing in computer screens. People were ripping wires out of the wall,” the same crew member told The Intercept. “By the time we landed, the plane was in total disrepair. We had screwed up the inside of that plane as much as we could.”

Other items were jettisoned through an emergency hatch.

Ultimately, it likely wasn’t enough.

Although the EP-3E hadn’t been upgraded to the latest standard, it was still an intelligence windfall for the Chinese. The United States later assessed that it was “highly probable” that China had obtained classified information from the aircraft.

A total of 16 cryptographic keys, other codebooks and laptops, and a computer used for signals intelligence processing, were all still intact. Tuners and processors for signals collection equipment were also mainly undamaged, as were cryptographic voice and data devices for communication and data transfer between the EP-3E and Kadena.

On arrival at Lingshui, the EP-3E was met by Chinese military trucks, which guided it to the end of the runway where soldiers surrounded it.

The crew were held for 11 days before being released and were regularly interrogated. Meanwhile, the United States secured the return of the EP-3E, which China said had to be dismantled first. This was done with the help of Lockheed Martin technicians. The spy plane was then flown back to the Marietta, Georgia, aboard two Antonov An-124 transports.

The spy plane was reassembled and repaired, adding parts from an NP-3D and the wings of a retired P-3B. It made its first flight after the rebuild on November 15, 2002, and then underwent maintenance and modernization with L3 in Waco, Texas, before being returned to service. It was still active as of September 2020, when it was photographed over the East China Sea, and was reportedly still in service as of April this year.

Osborn was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for “superb airmanship and courage” in nursing the damaged aircraft down safely and saving the lives of the crew.

Wei, meanwhile, was posthumously honored as a “Guardian of Territorial Airspace and Waters.”

In the meantime, Chinese fighters have continued to intercept Western surveillance aircraft, especially over the highly contested South China Sea.

So far, there has not been another incident as serious as that of April 1, 2001, but there have been close calls.

In October of last year, the Pentagon accused the pilot of a Chinese J-11 fighter of conducting an “unsafe intercept” of a .S. Air Force B-52H Stratofortress bomber over the highly contested South China Sea. You can read more about that incident here.

Earlier the same month, the Department of Defense released a collection of declassified images and videos that it says provide evidence of “a dangerous pattern of coercive and risky operational behavior by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) against U.S. aircraft operating lawfully in international airspace in the East and South China Sea.” The Pentagon said that there were more than 180 such interactions between the fall of 2021 and October 2023.

In one of those incidents, in May 2023, a J-16 fighter “flew directly in front of the nose” of a U.S. Air Force RC-135 surveillance aircraft, forcing it to fly through its wake turbulence — an action known as ‘headbutting’ or ‘thumping.’

Other examples include a simulated attack on a U.S. Navy task group and a close-proximity intercept of another RC-135 by a J-11 — as seen in the video below — both in December 2022.

More worrying was the incident in June 2022, when a Royal Australian Air Force P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft was reportedly damaged by countermeasures launched by a Chinese J-16, once again over the South China Sea.

As the Hainan Island demonstrates, the stakes have long been very high in these interactions over the South China Sea, especially since Beijing claims the vast majority of these waters as its own.

As of today, the EP-3E remains very much still involved in intelligence-gathering missions here and around other global hotspots. At one point, it seemed likely the last of these spy planes would cease operations by September 30, 2024, with the deactivation of VP-1 scheduled to follow in March 2025. However, operational demands have postponed this for the time being. Ultimately, however, the EP-3E’s days are now numbered with the MQ-4C Triton drone steadily replacing it.

While the events of April 1, 2001, could have ended much worse for the crew of the EP-3E, it’s highly appropriate that such a historic aircraft be preserved for public view. Not only does it stand testimony to the particular events of that day, but it also serves as a reminder of the constant risk that aerial reconnaissance crews are exposed to on missions of this kind.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com