The U.S. Air Force faces potentially serious operational, training, and testing challenges, and the risk of having to pay associated costs, if it gets rid of its 32 Block 20 F-22 Raptor stealth fighters, a Congressional watchdog has warned. The service’s assessment that it would be prohibitively expensive to bring these jets, which represent just shy of a fifth of the current Raptor fleet, up to a newer standard has also been called into question. The Air Force is already staring down looming budget cuts and growing questions and criticism about how far back it is trimming back its existing fleets, especially fighters, as it pushes ahead with its modernization plans.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) raised its questions and concerns about the Air Force’s plans for the 32 Block F-22s in a report released earlier today. The Air Force has been arguing for years now that it needs to retire these jets, which are currently relegated to test and training duties, to help free up funds for priority modernization efforts. The service is currently prohibited by law from divesting any portion of its fleet of just over 180 Raptors, the balance of which are upgraded Block 30 and 35 types, before the end of Fiscal Year 2027.

“The Air Force did not document how it will conduct F-22 training or testing – the current Block 20 functions – without Block 20 aircraft,” according to GAO. “It also did not document the challenges that combat units may face if mission-ready Block 30/35 aircraft are used for training or testing instead of Block 20s.”

Furthermore, “the Air Force stated that divestment would result in cost savings from not flying Block 20s,” per GAO’s new report. “These savings, however, did not account for other costs, such as maintenance for increased operations to make up for [having] less aircraft.”

At present, 90 percent of initial Air Force pilot training on the Raptor is conducted using Block 20 jets. The remaining 10 percent is conducted using Block 30/35 aircraft belonging to the operational units to which those pilots get assigned.

GAO’s points out that, absent some as yet unidentified alternative, without the Block 20 F-22s, the remaining Block 30/35 Raptors will have to take on all training responsibility. This, in turn, could easily have impacts on their operational availability and increase the general wear and tear on what are already notoriously maintenance-intensive planes. Some of the combat-coded portion of the F-22 fleet is currently tasked with critical homeland defense missions and is seen as an essential capability for combat operations down range, especially in any future high-end conflicts, such as one in the Pacific against China.

“Air Combat Command officials stated that combat units generally have a total of 24 Block 30/35 aircraft to ensure there are 12 mission capable aircraft at a given time, due to availability concerns such as maintenance,” GAO’s report explains. “However, if the Air Force reallocated Block 30/35 aircraft to training units to account for the loss of Block 20 aircraft, Air Force documentation noted this could potentially result in combat units having as few as 18 total aircraft.”

In addition, “Air Force officials and budget documentation did not specify whether the Air Force planned to accept lower performance or attempt to increase maintenance costs and tempo to achieve the same number of flights with fewer operational aircraft,” the new report from GAO adds. “According to budget decision briefs, neither the costs to increase maintenance nor the potential for fewer flights were factored into the Air Force’s decision-making process.”

The same kinds of cascading impact apply to testing capacity. The F-22 fleet is small to begin with, a byproduct of what has turned out to be a very short-sighted decision in the late 2000s to dramatically curtail total production. Two of the Block 20 jets are part of the even smaller dedicated test and evaluation force for the Raptor. In addition to supporting work on critical upgrades for the F-22s, like new infrared search and track (IRST) systems and stealthy drop tanks, test Raptors are being used as incubators of sorts for technologies that will feed into the Air Force’s Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) initiative. F-22s could also benefit from those developments in the near term.

NGAD is the Air Force’s current flagship modernization effort and includes a number of subprograms, such as the development of a new sixth-generation crewed stealth combat jet intended to ultimately supplant the F-22s. Hundreds, if not thousands of highly autonomous Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) drones intended to work cooperatively with crewed fighters, as well as new weapons, sensors, networking and battle management capabilities, advanced jet engines, and more are also part of the larger NGAD ‘system of systems,’ as you can learn more about here.

The need to fund NGAD has been one of the Air Force’s core arguments for retiring the 32 Block 20 F-22s.

A proposal from the service to repeal the current legislation blocking Raptors retirements “stated that from fiscal years 2024 to 2028, the Air Force estimated that it would save a total of approximately $1.8 billion from divesting the Block 20 aircraft instead of operating and maintaining them,” according to GAO. However, “neither the fiscal year 2023 budget information nor the proposal to remove the legislative prohibition on divestment included supporting information on training, mission capability, testing, or potential future costs of divestment.”

The Air Force does not appear to have directly challenged any of these assessments, but has continued to push for the divestment of the Block 20 Raptors.

The Air Force “cited the National Defense Strategy, as well as the Defense Planning Guidance, which the [service] … said directed it to take risk in the near term to modernize for the mid- and far-term China fight. It further stated that it selected the F-22 Block 20 aircraft for divestment based on factors such as: (1) the least number of aircraft affected, (2) operational cost, and (3) the aircraft being not-combat capable against China,” per GAO. “The Air Force’s comments noted that while more information can be useful in divestment decisions, Air Force leadership assessed the cost and schedule risks of maintaining F-22 Block 20 aircraft to be too great based on the information already gathered.”

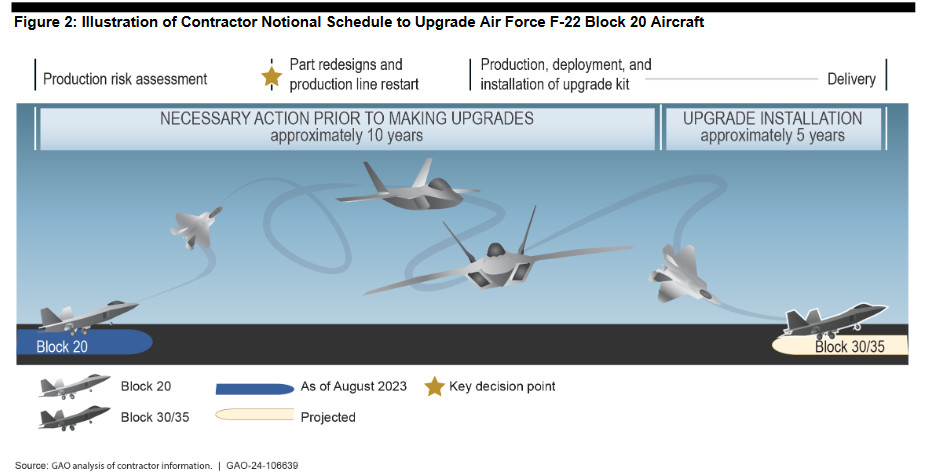

GAO has also now challenged the assertion that it would be cost-prohibitive to upgrade the Block 20 F-22s to a newer standard based on the information at hand. The prime contractor for the Raptor (which GAO’s report does not name, but is Lockheed Martin) has estimated that it would take $3.3 billion and 15 years to bring the 32 jets up to a Block 30 or 35 standard, according to the Air Force. The Congressional watchdog says Lockheed Martin provided no supporting data for how it reached that conclusion, but that the Air Force still “determined this information was sufficient for its purposes.”

Lockheed Martin did tell GAO that it had “based these costs in part on the data it provided to the Air Force to help it prepare a 2017 report to Congress on the cost to upgrade the Block 20,” which laid out an 11-year schedule at a total cost of $1.7 billion in Fiscal Year 2018 dollars. “A contractor representative stated that they used the cost figures reflected in the report and adjusted them to account for inflation and any capabilities added from 2017 to approximately 2027.”

GAO says that Lockheed Martin representatives described the 15-year upgrade schedule, outlined in the graphic below, as “very notional,” as well.

In response to GAO’s findings, the Air Force summarized “the key factors it says were involved with making this decision, it did not provide documentation that quantified or documented the cost, schedule, and risks associated with upgrading these aircraft. The Air Force stated that it deemed the level of detail in the contractor’s estimate sufficient to defer investing in the Block 20 aircraft,” according to the new report. The service “also acknowledged that further studies could provide added clarity or validate data provided by the contractor but postulated that these studies would not have substantially changed the considerations that drove its decisions. However, the cost and schedule data cited by the Air Force were acknowledged as being only notional.”

GAO’s new F-22 report can only raise additional questions in light of recent statements from top Air Force officials warning about the potential for significant future budget cuts. Those same officials have highlighted concerns about whether the service has been taking on too much risk in its divestments of current fleets to support future modernization priorities.

“There are a lot of things that we probably might not have contemplated a few years ago, we’re taking a hard look at,” Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall said about the forthcoming proposed budget for the Fiscal Year 2026 budget in an interview with Aviation Week that was published last week.

“The way we were able to put together a five-year plan and submit it was through taking—what I think ultimately will turn out to be—unacceptable reductions in current force and sustainment,” Kendall also said, according to a follow-up report yesterday from Aviation Week.

“The deliberations are still underway, there’s been no decision made,” Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Allvin also said a a roundtable with reporters last Friday when asked about the potential for cuts to NGAD, according to Breaking Defense. “We’re looking at a lot of very difficult options that we have to consider.”

The Air Force’s budget in Fiscal year 2026 will be “very, very thin across the board,” Allvin had said during a separate talk that the Air & Space Forces Association hosted last week.

Cuts and/or other delays with progress on the NGAD combat jet program, specifically, could have direct impacts on the F-22 fleet and what will be demanded of it going forward. There have already been concerns for years now about the Raptors being stretched too thin, both in terms of roles and missions and physical bases, for the Air Force to get the most out of the jets. There has been some consolidation of F-22 operating locations in recent years, in part as a result of Hurricane Michael devastating Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida in 2018.

If the Air Force continues to be insistent on pushing ahead with plans to retire the Block 20 F-22s before the 2027-2028 timeframe, one option for mitigating the impacts of the divestments could be to end the practice of having Raptors sit alert in support of the homeland defense mission. F-22s fly those missions with external drop tanks that negatively impact their stealthy characteristics. The re-designation earlier this year of an aggressor unit in Alaska equipped with F-16C/D Viper fighters as the Air Force’s first Fighter Interceptor Squadron in decades with a focus on protecting the homeland raised the possibility of that a realignment might already be coming.

In response to queries from The War Zone back in April, the Air Force declined to say whether or not it had any plans to alter the use of F-22 in support of the homeland defense mission in any way.

As already noted, the Air Force is currently prohibited from retiring any F-22s for at least another three years or so regardless of the issues cited in GAO’s new report. The service’s budgetary and force posture outlooks appear set to change significantly well before 2027, which may render the entire discussion moot.

Whatever the case, the Air Force’s prospects for getting rid of the 32 Block 20 Raptors in the short term look to be diminishing amid questions about capability gaps and projected cost savings.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com