China’s development of uncrewed cargo aircraft continues apace, with the ongoing Airshow China including the first public appearance of the W5000, the biggest that we’ve seen so far, as well as a full-size mockup of one that can also operate from water, and a new concept for an air-launched cargo drone. China now has a multitude of cargo drones in development or under flight test, and beyond their clear civilian applications, their potential utility for helping maintain military logistics networks is very clear.

The various cargo drones are displayed at Airshow China, also known as the China International Aviation & Aerospace Exhibition, in Zhuhai. The event officially opened today and runs until November 17.

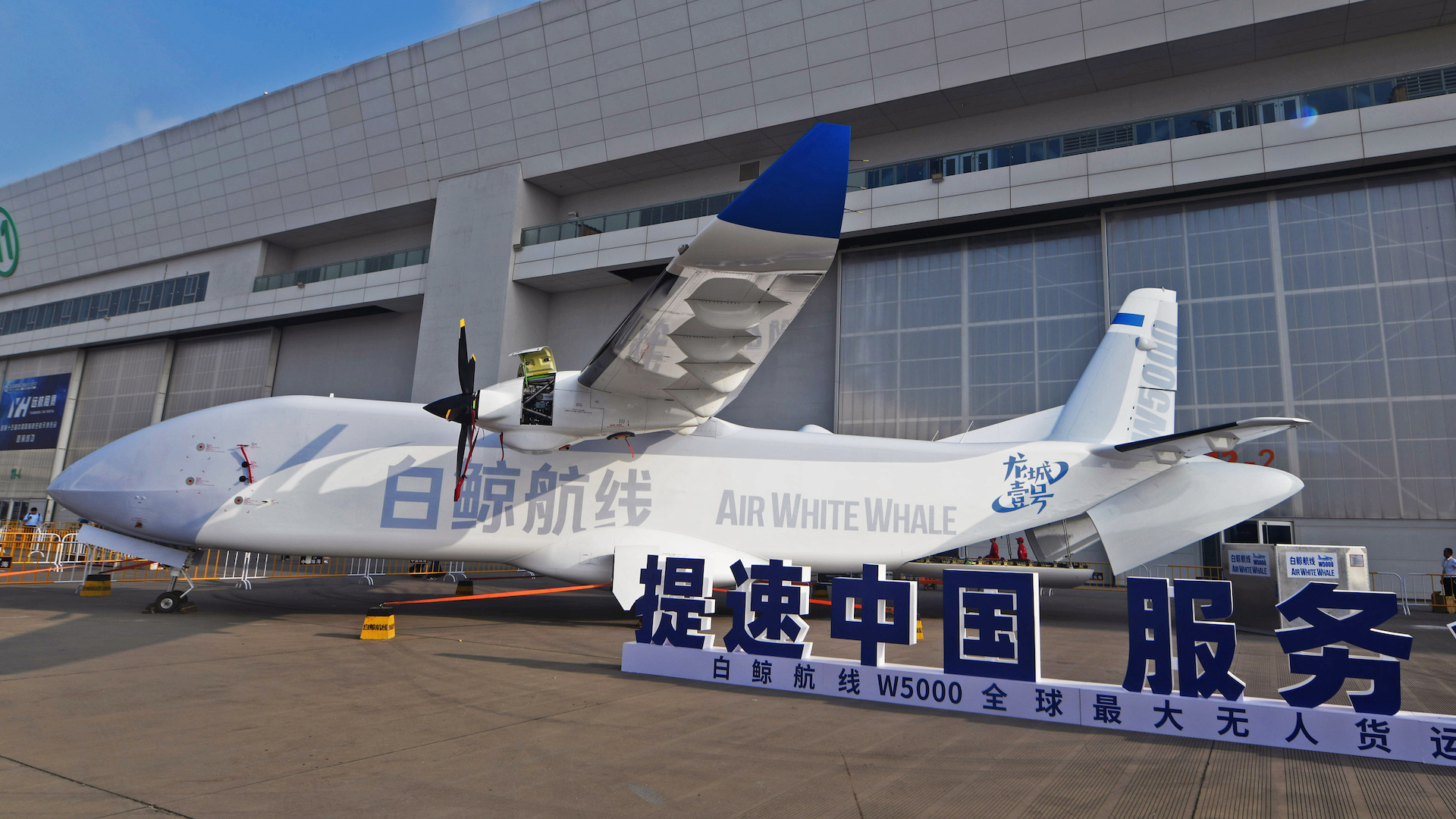

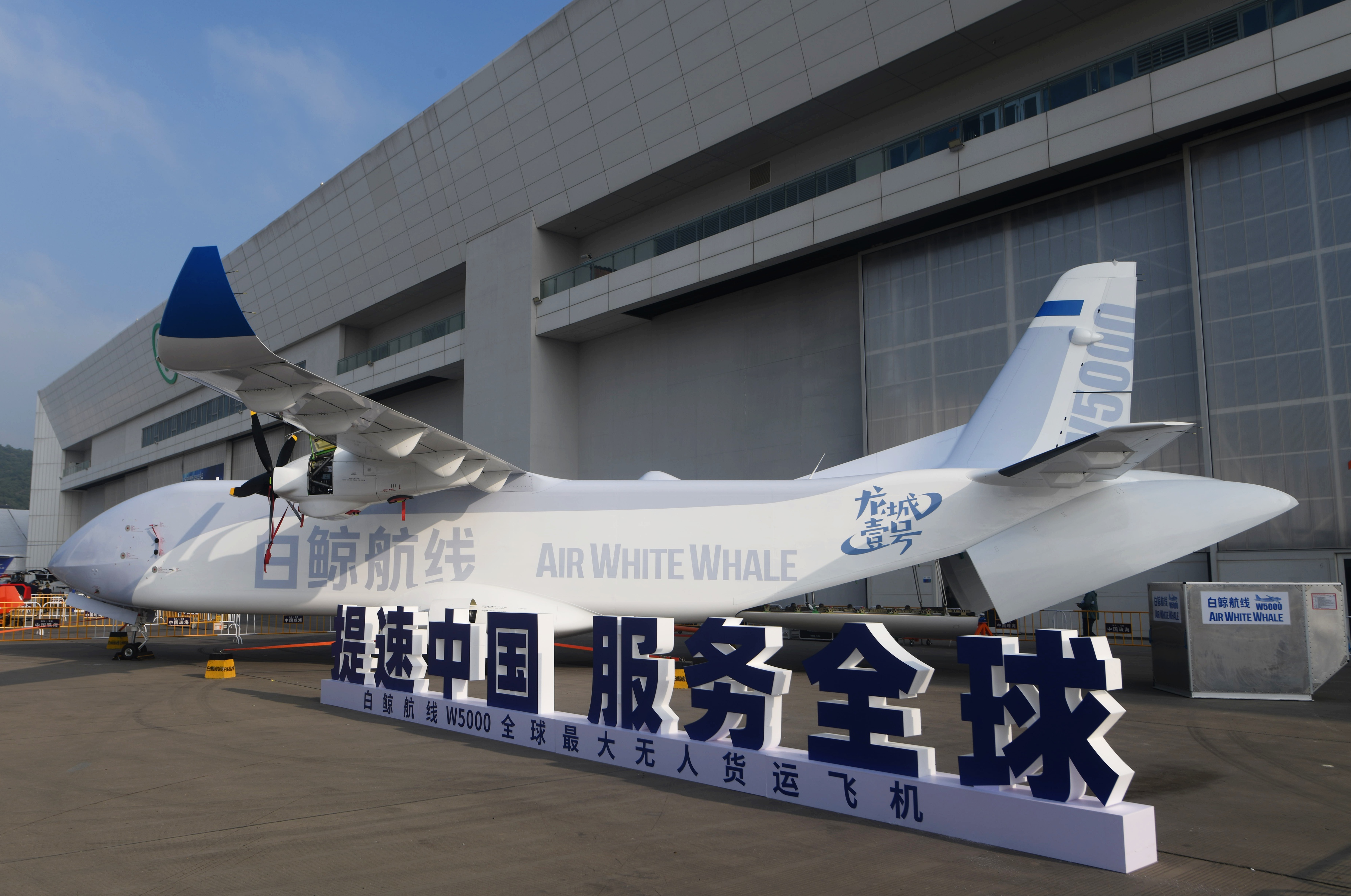

The big W5000 is from the Air White Whale company. This uncrewed cargo aircraft was unveiled last month when the first example rolled off the production line in the eastern Chinese city of Changzhou. A real example of the drone is part of the static display at Airshow China.

The W5000 is named for its payload of 5,000 kilograms — 11,023 pounds — and is said to have a maximum range of 2,600 kilometers (1,616 miles), with a cruising speed of up to 526 km/h (284 knots). The maximum takeoff weight of the drone is 10,800 kilograms (23,810 pounds).

In comparison, the Xi’an Y-7 — a Chinese-produced version of the Soviet-era An-26 twin turboprop — still the main mid-size tactical transport used in China, has a payload of 5,500 kilograms (12,125 pounds).

Reportedly, the high-wing, twin-engine W5000 is powered by AEP-100 turboprops, which is produced by Aero Engine Corporation of China.

According to Air White Whale, the W5000 is compatible with standard cargo pallets, which can be loaded and unloaded via a rear ramp and clamshell-type doors in the rear fuselage. The drone is designed to be able to use smaller general aviation airports as well as commercial aviation airports.

The ground control system for the W5000 is said to allow a single operator to monitor up to five of the drones simultaneously.

When announced, Air White Whale said it had submitted certification documents for the W5000 to Chinese regulators and expected to deliver the first aircraft in the second half of 2026.

The unveiling ceremony for the W5000 on October 18 was attended by executives from different cargo and logistics firms, including JD.com, China Eastern Airlines Logistics, as well as China Post, suggesting one or more of these can be likely launch customers.

However, the W5000 would appear to have obvious military applications, too.

TWZ has already looked in detail at a similar Chinese uncrewed cargo aircraft, from the Tengen company, another high-wing, twin-engine design, but with a payload capacity of around 2,000 kilograms (4,410 pounds).

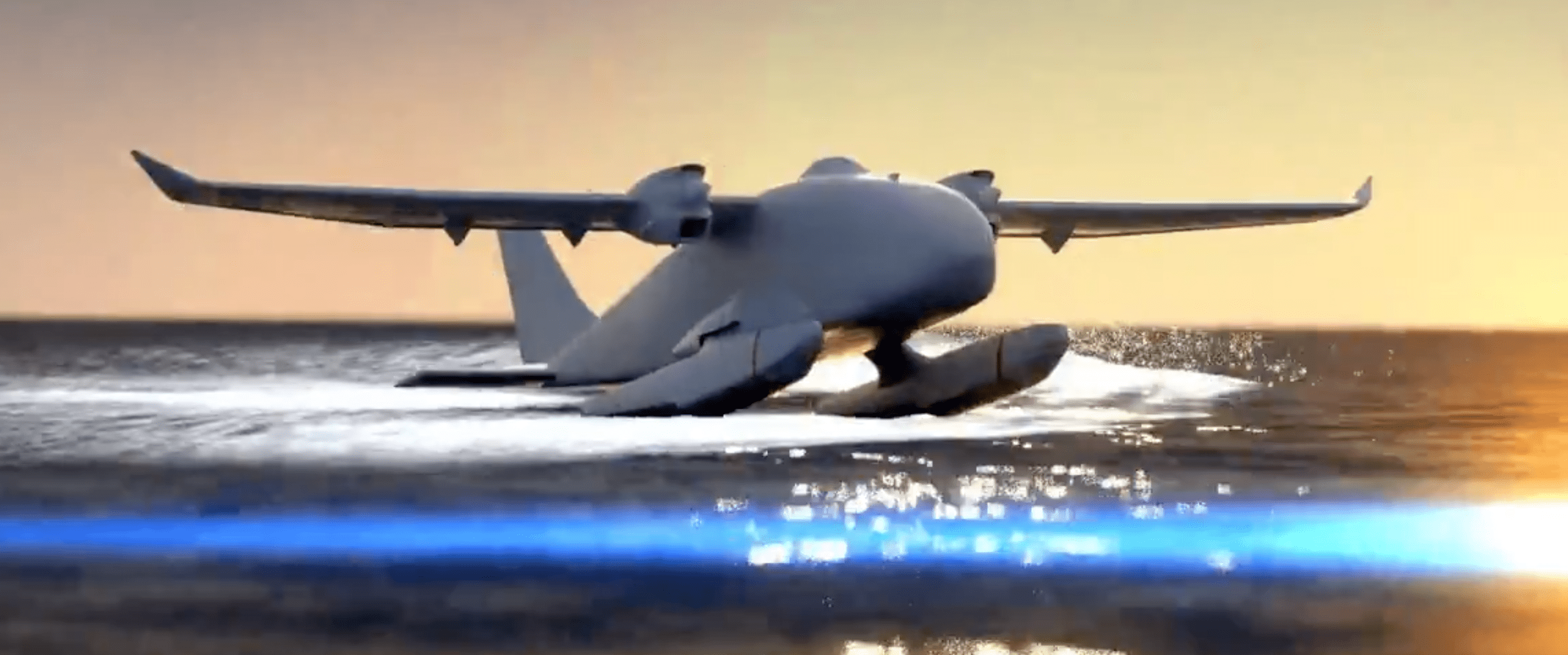

Making its public debut at Airshow China, after having been announced last week, the CH-YH1000 uncrewed cargo aircraft has been developed by the state-owned China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC). This design was shown in mockup form and in a promotional video.

Smaller than either the W5000 or the Tengen drone, the CH-YH1000 is said to have a payload capacity of around 1,000 kilograms (2,204 pounds), a maximum takeoff weight of 2,300 kilograms (5,071 pounds), a ceiling of 8,000 meters (26,247 feet), and a mission endurance of around 10 hours.

The CH-YH1000 can accommodate different types of standard cargo pallets, which can be loaded and unloaded via the visor-type upward-opening nose door and via a rear ramp.

Interestingly, the CH-YH1000 is already being pitched directly to the military, as well as commercial and other government operators. CASC’s promotional video shows versions of the drone being used for airdropping cargo loads, as well as dropping precision-guided munitions against a land target from a weapons bay in the lower fuselage.

Most intriguingly, as well as having the option of tricycle landing gear to take off and land from traditional runaways, the CH-YH1000 can also be adapted for operations from water, taking off and landing using a pair of pontoon-type floats that are attached to either side of the lower fuselage. As well as cargo operations from water, this option means the CH-YH1000 is being pitched for specific maritime operations including search and rescue, reconnaissance, and anti-submarine warfare. Still, operating a drone like this from a variable operating surface like water would pose some real challenges.

As noted earlier, these are not the first Chinese uncrewed cargo aircraft to have emerged in recent years. The state-run Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC) has developed the HH-100 cargo drone, with a stated payload capacity of around 700 kilograms (some 1,543 pounds).

The Tengen company, too, has flown another cargo drone, the TB-001D Scorpion D, which began to be tested in 2022, which you can read about here. This is a four-turboprop design with a stated payload capacity of 1,500 kilograms (3,307 pounds).

Other Chinese firms are working on larger cargo-carrying drone designs, as well.

All this activity is perhaps not surprising considering the lead taken by Chinese companies in conducting uncrewed commercial cargo flights, including using Feihong-98 (FH-98) drones, a biplane design based on the Yun-5B — itself a Chinese copy of the famous Soviet-era Antonov An-2.

Although China is busy building traditional cargo aircraft, spearheaded by the increasingly capable Y-20 family, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has a clear requirement for moving supplies in and out of a growing number of remote and austere locations, often with limited runway capacity. Chief among these are the highly strategic island outposts cropping up across the South China Sea.

It’s easy to imagine how uncrewed platforms could be ideal for routine resupply operations into such locations, not all of which might even be able to accept crewed cargo aircraft, or which might not be able to do so safely or efficiently.

Outside of the South China Sea, there are plenty of other applications for PLA cargo drones, including some of the remote facilities on land in Western China, where the Chinese military presence is expanding and existing infrastructure is very often spartan. At the same time, the high altitudes involved in this region can be a challenge for some traditional transport aircraft.

As we have discussed before, the PLA has a clear interest in further developing its capability to conduct expeditionary operations further and further from the Chinese mainland. Bearing in mind the kinds of challenges that any armed forces would face in an active conflict or other high-risk scenario in the Pacific theater, the option of having a fleet of cargo drones to help maintain logistics here would surely be attractive to the PLA. In particular, drones would be preferable for flying supplies into particularly hazardous locales, without having to expose the crew of a cargo plane to additional risk.

Similar thinking is also evident in the U.S. military now, in particular the U.S. Marine Corps, which is also increasingly looking to introduce multiple tiers of cargo-carrying uncrewed aerial systems to help support future expeditionary and distributed operations. Once again, the demands of the Pacific theater are very much a driver here. So far, however, the kinds of cargo drones being eyed by the U.S. military are smaller and shorter-ranged than many of the designs now coming out of China.

Overall, the U.S. military seems to be facing a growing airlift problem, especially in view of a potential confrontation with China in the Pacific. While there has been talk of uncrewed transport platforms, most concepts so far have focused on optionally crewed solutions. This is less satisfactory bearing in mind the much greater scale of the logistical challenge facing the United States compared with China when fighting in the Indo-Pacific region. Meanwhile, existing U.S. airlifters and tankers are increasingly being eyed for new roles on top of their basic transport tasks.

Speaking last month, Brig. Gen. Shane Upton, director of the U.S. Army’s Contested Logistics Cross-Functional Team, reflected upon the scale of the challenge for the U.S. military. He told Breaking Defense, “We’re going to have to figure out how to resupply dispersed formations.”

“The Pacific, by nature, drives you to that. There’s no other option if you start putting a Multi-Domain Task Force lethal firing asset on a remote island chain, I have to resupply them with ammo and we may not be able to fly a traditional C-17 or C-130 in there,” Upton added. “The enemy will be like: ‘You’re not using that port because I just shot it up and it’s gone.’”

Finally, another type of cargo drone being shown at Zhuhai is CASC’s CH-103 (or Caihong-103, meaning Rainbow-103), described as a precision airdrop system and similar in concept to uncrewed cargo gliders that have been developed in the United States.

The manufacturer’s specifications for the CH-103 include a payload capacity of 200 kilograms (441 pounds), a maximum drop altitude of 3,000 meters (9,843 feet), and a maximum landing error of within 100 meters (328 feet). The range of the cargo glider was not stated and it’s unclear which transport aircraft it’s intended to be deployed from. The guidance system is also unclear, but some kind of inertial navigation system seems most likely at this point.

This year’s Airshow China has already brought its fair share of surprises, but the prominent place taken by uncrewed cargo aircraft designs—including newly developed ones—demonstrates just how much importance is being assigned to this sector. For the most part, this growing number of ever-larger and more capable cargo drones are being offered primarily for commercial applications. At the same time, however, the military value of these drones in terms of aerial logistics capabilities is unquestionable.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com