A new miniature electronic warfare jammer that is relatively low-cost enough to be a payload on loyal wingman-type drones and even expandable loitering munitions has hit the market from defense contractor Leonardo. Focused on stand-in jamming, the BriteStorm payload is based on technology pioneered in the BriteCloud air-launched decoy, which The War Zone has covered in detail in the past. Like its predecessor, BriteStorm can scoop up hostile radar emissions and emulate returns to create large numbers of false and confusing ‘ghost’ tracks and can also execute more traditional jamming, with even more adaptive capabilities on the horizon.

Leonardo, which is headquartered in Italy, officially unveiled BriteStorm at the Association of the U.S. Army’s main annual conference, which opened today in Washington, D.C. The company’s subsidiary based in the United Kingdom has led the development of the new jammer, as well as the preceding BriteCloud decoy.

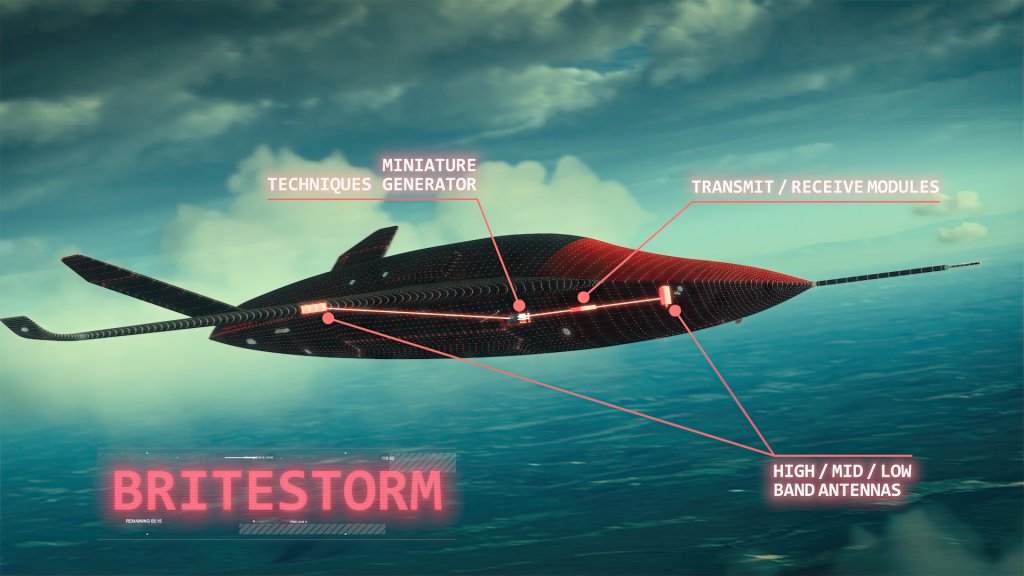

“A standard BriteStorm fit incorporates a platform-specific antenna, transmit-receive modules and Leonardo’s Miniature Technique Generator,” according to a press release today from Leonardo. BriteStorm weighs just five and a half pounds (two and a half kilograms), the company also told Breaking Defense. This is small, but still substantially heavier than the soda can-sized BriteCloud, which weighs just over a pound (or half a kilogram).

“BriteStorm is platform agnostic… You can put it on almost anything, as long as it has a payload bay and the power of equivalent of something like a Humvee battery,” Michael Lea, Vice President Of Sales for Electronic Warfare at Leonardo, told The War Zone and other attendees at AUSA. “And when it comes to price, BriteStorm has been designed to sit at a point that makes it attritable. … [meaning it] is not prohibitively expensive, and it won’t cause a major strategic, strategic issue if lost.”

Lea did not further elaborate on cost.

BriteStorm is focused on providing stand-in jamming support – which Leonardo defines as an “airborne electronic warfare capability, deployed ahead of the main force, to deliver high-powered interference against a wide spectrum of threats” – while installed on any of a variety of different platforms. “By doing so, BriteStorm degrades the enemy’s IADS [integrated air defense system network], supressing its ability to detect and lock onto other platforms, protecting friendly forces and enabling their mission,” according to a company press release.

When it comes to how the system works, regardless of what it is installed on, “BriteStorm is the first stand-in jammer on the market to use the gold-standard digital radio frequency memory, or DRFM, technology, which means it can record the pulse of an enemy radar system perfectly,” Lea added. “The pulse is then manipulated and projected back, confusing the enemy and significantly degrading their situational awareness.”

BriteStorm’s DRFM capabilities are based on those found on the BriteCloud decoy, which has been seeing increasing sales worldwide, most recently as a new addition to the F-35 stealth fighter’s array of radiofrequency countermeasures.

It is worth noting here Leonardo’s division in the United Kingdom has also been supplying the electronic warfare payload for the still-in-development stand-in jammer derivative of the Select Precision Effects At Range Capability Three (SPEAR-3) mini-cruise missile from European consortium MBDA. The SPEAR-EW version has been leveraging past work on BriteCloud.

“BriteStorm is highly effective against radars in the NATO A to J bands,” the Leonardo executive continued. “This means that BriteStorm is effective against all types of… surveillance, target acquisition, and tracking radars.”

As The War Zone has highlighted in the past with regard to BriteCloud, DRFM’s signal mimicry can take the form of entire fleets of illusionary targets, not only confusing, but overwhelming radar operators. Integrated onto aerial drones or other uncrewed platforms, the new BriteStorm jammers could also be sent into a target area from multiple different vectors at once, creating additional problems for enemy defenders trying to prioritize their resources.

Leonardo says that BriteStorm can also work by using more traditional jamming functionality, “barraging the enemy system with electronic noise.”

As such, BriteStorm jammers could help shield friendly crewed and uncrewed aircraft, as well as cruise missiles, from hostile air defenses, including drawing away surface-to-air missiles from the primary force. Just stimulating the enemy’s defenses could help assets tasked with suppression and destruction of enemy air defenses, allowing them to cut a clear path to a target area for incoming strikers.

Leonardo’s LEA specifically highlighted the U.S. Army’s Air Launch Effects (ALE) and Future Tactical Uncrewed Aircraft System (FTUAS) programs, the U.S. Air Force’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) program, and the United Kingdom’s Autonomous Collaborative Platforms (ACP) drone program as ones that the company is now eying as potential opportunities for BriteStorm. Leonardo has three unspecified aerial assets in the United States now that it is using to demonstrate the capability to potential customers.

In the United Kingdom, the Royal Air Force’s (RAF) Rapid Capabilities Office (RCO) has already taken delivery of several BriteStorm payloads and has conducted some degree of flight testing. Leonardo already conducted at least one test back in 2020 in cooperation with the RAF RCO that involved a group of drones employing BriteCloud decoys against a mock enemy integrated air defense network.

“We’re having quite interesting conversations with a number of end users about CONOPS [concepts of operations] for operation of BriteStorm at the moment,” Leonardo’s Lea said. “And I think it’s fair to say that in the world of CCA and ACP, coalition forces are trying to work out the right force mix between large, exquisite platforms, uncrewed platforms, and then potential attritable platforms, as well.”

In addition, “BriteStorm is supplied with a very comprehensive mission data and generation tool. And you can observe the effects BriteStorm… has on opposition radars, and then reprogram it, depending on what you’ve seen and the threat that’s out there,” Michael Lea from Leonardo explained today. “We are looking again in the capability roadmap, about how you may change the waveforms that BriteStorm can generate by connecting it back to other systems, which are elsewhere.”

Responding to a question at the roll-out presentation at AUSA from The War Zone‘s Jamie Hunter about whether this might mean the system could be reprogrammed on the fly, representatives from Leonardo said the current plan is for any changes to be made in between missions. No mention was made of so-called cognitive electronic warfare capabilities in regard to BriteStorm, but remote updating of systems in the middle of operations to respond to new and evolving threats is a key part of that overall concept. An electronic warfare suite that can process incoming signals and autonomously adjust its outputs to be most effective in response without any outside input is the absolute “holy grail” that the concept envisions, as you can read more about here.

No explicit mention was made today about networking BriteStorms together, but doing so would provide critical additional capability. A networked group of platforms carrying the electronic warfare systems would have synergistic effects. It would make it harder for an opponent to realize they’ve been deceived and how, with multiple coordinated EW tactics occurring over a broad area and from different vectors and platforms. A grouping like this would also be more resilient to attacks since it would still be able to continue its electronic attacks even if some of the platforms in the network are lost.

It’s interesting to point out here that the U.S. Navy has been pushing ahead in recent years with plans for a similar-sounding distributed and deeply networked electronic warfare ecosystem that includes uncrewed decoys and other nodes capable of mimicking friendly forces to protect them from threats and deceive opponents. The Navy has referred to this concept in the past as the Netted Emulation of Multi-Element Signature against Integrated Sensors, or NEMESIS, which The War Zone was first to really report on. We have highlighted in the past that some of these developments might help explain some number of sightings of so-called unexplained aerial phenomena (UAP).

Furthermore, Leonardo’s unveiling BriteStorm at the AUSA conference raises the question of whether the system might be usable against target sets beyond enemy air defense networks. Preventing enemy counter-battery radars from getting an accurate fix on artillery units or coastal radars from spotting and tracking ships at sea would also be valuable capabilities to have.

More generally, BriteStorm reflects a broad resurgence of demand in the West, especially within the U.S. military, in higher-end electronic warfare capabilities that had increasingly fallen into disuse after decades of counter-terrorism and other lower-intensity missions. American officials now regularly talk about how dominating in the electromagnetic spectrum will be a key factor in succeeding in future high-end fights, such as one in the Pacific against China. The ongoing war in Ukraine has only provided further evidence of the importance of various tiers of electronic warfare capabilities, as well as an important source of more direct lessons learned for the United States and others.

How and where BriteStorm may be fielded operationally in the future remains to be seen, but the U.S. military and other armed forces globally have clear and still-growing interest in the kinds of distributed electronic warfare capabilities it has to offer.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com