Boeing is busily planning for future upgrades to the AH-64 Apache attack helicopter. While the scope of what is tentatively known as the Modernized Apache has been scaled back somewhat compared to how it once looked, the company is considering the lessons of the war in Ukraine as it seeks to optimize the AH-64 so that it can continue to serve the U.S. Army into the 2060s. Long before that time, it will be operating alongside the Army’s Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) tiltrotor, which will bring a whole new set of capabilities — and new challenges — for the Apache.

The War Zone spoke exclusively to T.J. Jamison, Boeing’s business development director for the Apache and for the AH-6 Little Bird. Jamison, a retired U.S. Army aviator, commanded an aviation squadron in Iraq and an aviation brigade in Afghanistan, with 72 Apaches under his command at one point in the latter theater.

As the largest Apache operator, the U.S. Army’s program of record currently covers 791 of the attack helicopters, with 91 of the older AH-64D Longbow, or ‘Delta’ models, in service right now. Some of the U.S. Army Deltas are still passing through Boeing’s remanufacturing program, where they emerge as the improved AH-64E Apache Guardian, or ‘Echo’ versions.

The size of the U.S. Army’s Apache fleet is determined by the organizational structure, in which there’s an attack battalion and an air cavalry squadron in each combat aviation brigade for each division. This makes it one of the very few customers who, in Jamison’s words, “can truly fight with the Apache as a maneuver element in an air-ground integration concept, out there on the battlefield.”

While this was the Cold War style of combat that the Apache was designed for, in more recent decades the helicopter was employed by the U.S. Army almost exclusively in a counterinsurgency (COIN) concept of operations in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Now, with the war in Ukraine, the pendulum is swinging back toward something closer to the Cold War model, reflected in growing interest in the Apache in Europe.

Returning to the U.S. Army, as Jamison explains, the reason those last 91 Deltas have not yet been upgraded to the definitive standard is that they were previously due to be replaced in air cavalry squadrons by the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA). This was one of the U.S. Army’s highest-profile aviation programs until its cancelation earlier this year. That decision, which we discussed in detail, has an effect on the Apache force but, more critically, makes the AH-64 an even more critical asset for the Army and refocuses efforts to keep it effective and relevant for another four decades or more.

“Now that FARA has gone, the Army’s got to make a decision on what to do with these 91 Deltas,” Jamison said. “Do they send them back to us to get remanufactured into Echos? What they do with the 91 is their decision.”

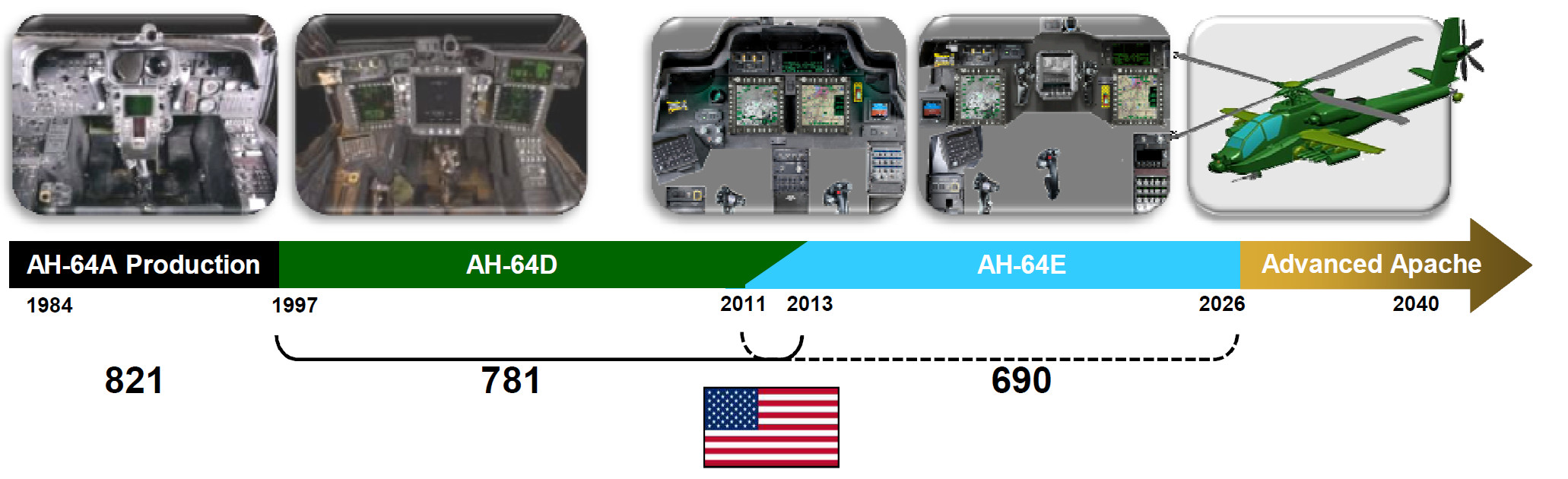

Apache genesis

Before looking at what comes next — and after the AH-64E — it’s worth looking at the evolution of the Apache, and the different drivers that have influenced its continued development since it first flew back in 1975 and after the introduction of the initial AH-64A, or Alpha model, in 1984.

“When this aircraft first came about as an Alpha-model aircraft back in the 1980s, it was specifically designed for large-scale combat operations,” Jamison explained. Under the AirLand Battle doctrine devised in that decade, the AH-64A was intended to fight on the plains of Europe against a high-intensity, near-peer adversary — the massed armored formations of the Warsaw Pact.

“I think a lot of people have kind of forgotten that, because of the incredible success that we observed with this aircraft in the counterinsurgency environment in Iraq and Afghanistan,” Jamison added. “But now, as we have transitioned out of that type of warfare and are now focused on large-scale combat operations in the European theater and obviously in the Pacific area of responsibility, people have forgotten that this is what this aircraft was originally designed to do.”

It’s very notable that, with the exception of the Apache, each one of the so-called Big Five programs that were central to U.S. Army modernization during the late 1970s and 1980s — the M1 Abrams main battle tank, the UH-60 Black Hawk utility and transport helicopter, the M2 and M3 Bradley fighting vehicles, and the Patriot air defense missile system — have all had a significant impact in the war in Ukraine, entering a European war decades after they were devised, but no less relevant with the passage of time.

Sgt. Aaron Ellerman

After the fielding of the AH-64D in 1997, the crew experience changed radically with the introduction of an all-glass cockpit, but it was the Longbow fire-control radar that made the biggest difference in terms of capability. Now, rapid engagements of multiple targets at once were possible by only exposing the Delta’s mast-mounted radar dish above the tree line or another kind of cover, before popping up to fire a missile.

The Delta also brought other significant advances, including the first iteration of manned-unmanned teaming and the Arrowhead, or Modernized Target Acquisition and Designation Sight (M-TADS). Less obvious was the addition of a Link 16 data link, which was, Jamison admits, “quite frankly, a little cumbersome.”

Adding all this equipment bestowed new capabilities but also meant the airframe was gaining weight. “In the Delta model, we started to lose that sports-car-like performance that we had with the Alpha, so that drove us to the Echo model, where the big changes are a new drivetrain, a new transmission to allow us to unlock additional horsepower through the T700-701D engines.”

The AH-64E therefore returned a more sprightly performance and because of that boost, more capabilities could be accommodated. The Echo features fully integrated Link 16, for a “much more seamless, easier-to-use capability” and significant improvements were also made to manned-unmanned teaming. Improvements to the radar saw its range extended from five miles all the way up to 10 miles.

The improved radar in the Echo not only allows targets to be engaged at greater distances, but a new advanced air-to-air mode sets the Apache up for kinetic engagements in the counter-unmanned aircraft system (UAS) mission, something that is of increasing importance for the U.S. Army and others, and which Jamison expects will be further expanded upon in future upgrades.

“The other thing we added in [the Echo model] was a maritime mode, where the radar will identify classes of vessels at sea, regardless of sea states,” Jamison said. Previously, higher waves were a major challenge for the Apache’s radar, and identifying maritime targets is of obvious relevance in the Pacific theater.

Version 6.5

The Echo versions started out with Version 1 and by now Version 4.5 is a common standard among different operators. Meanwhile, Version 6 is coming off the production line today, and Boeing is under contract for V6.5, a configuration that first flew in October of 2023.

“We’re continuing to do testing and flight developments on V6.5. For the customer, it’s going to bring a common configuration of software across the entire fleet,” Jamison said. “Right now, if you go from one aviation brigade in the U.S. Army, let’s say at Fort Campbell, and then you go to Fort Novosel, or Joint Base Lewis–McChord, there’s a good chance that you’re going to have a different version of the Echo models, and you’ll have to do some transition training.”

V6.5 will simplify the U.S. Army’s Apache fleet and give them some new capabilities, mostly at the software level.

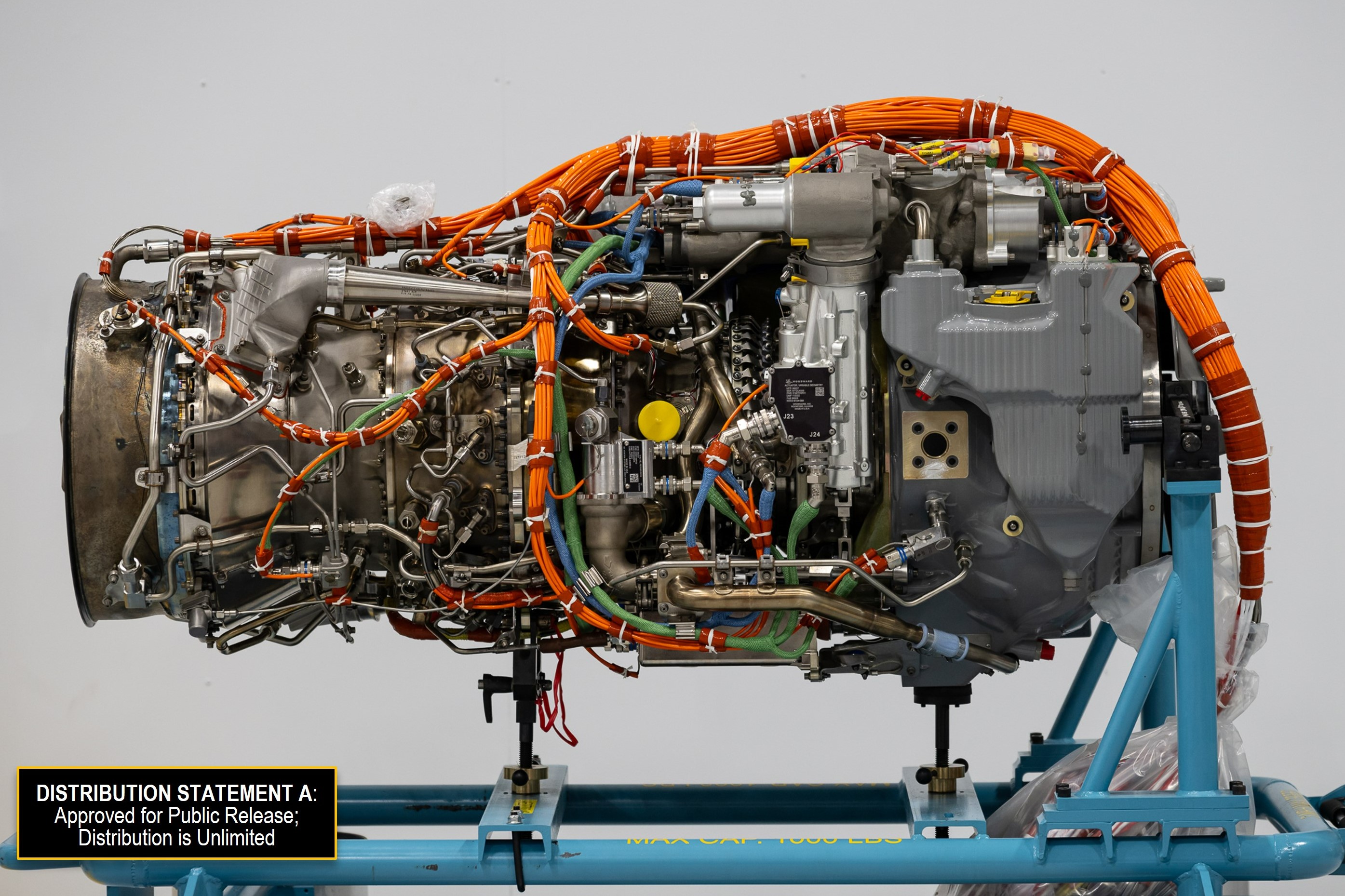

Jamison highlights one of the biggest advantages of the new software and one that should play a big part in the Apache’s future development path, namely setting the helicopter up for the future integration of the General Electric T901 turboshaft engine developed under the Improved Turbine Engine Program (ITEP).

“We’ve incorporated future growth into the V6.5 to integrate capabilities that, heck, we may not even know about right now, that are still out there in the development stage,” Jamison said. “By having an open systems architecture, just like with your iPhone, we can get software updates fully integrated. When you have to integrate something like Link 16 or whatever that next capability will be, you don’t have to send it back to the factory. We don’t have to go in there and do significant software upgrades.”

Jamison described a recent Boeing demonstration where a third party brought in a radio, that had never been put into an Apache, and installed it while the Boeing engineers stood back and watched their ‘plug and play’ integration of that radio. “That may sound simple, but it really is not. It’s really a lot more technical than you would think, but they were able to do that without any Boeing assistance,” Jamison recalled. “So that’s where we’re headed because that sets us up for future growth into the next-generation Apache.”

As to what that next-generation Apache looks like, that’s still somewhat unclear, but Boeing expects the U.S. Army will want to keep flying the attack helicopter into the 2060s timeframe.

That will involve a lot of potential changes to the helicopter, which is why the open architecture is now being prioritized, allowing simpler and more cost-effective integration of future capabilities.

Advanced flight controls

Another area of future development is advanced flight controls, in the form of the Active Parallel Actuation System (APAS). “This is a system where we’re doing everything we can to reduce the pilot workload in the cockpit as these new capabilities come on board, particularly with counter-UAS lessons learned from Ukraine, bringing in more Link 16, Launched Effects, and other things that we don’t even know about yet,” Jamison said. “Five, 10, or 15 years down the road, we know we have the potential to overwhelm the crew, so we’re doing things to reduce pilot workload, and one of those is the advanced flight controls.”

As far as the pilot is concerned, the advanced flight controls add soft stops to the controls, as Jamison explains. “Imagine, as you’re pulling in power, and you’re about to reach a power limit, a torque limit if you had a soft stop built into those controls where you felt it, a physical and tactile feel where you had to pull through that, versus getting your head in the cockpit looking at a gauge instead of looking outside where the threat is. That’s the whole concept behind the advanced flight controls.”

Launched Effects

Launched Effects are a growing area of interest for the U.S. Army, especially. At one point, the service described a future family of Air-Launched Effects (ALE), small uncrewed aerial systems that could be adapted for a range of missions, not only limited to standoff attack, but also including surveillance, electronic warfare, communications relay, and serving as decoys. The Army now refers to these simply as Launched Effects, reflecting the fact that some are likely to be deployed from dismounted launchers on the ground or from vehicles, as well as from aircraft.

New helmet display

Among the pilot aids that Boeing is now working on is a follow-on to the current Integrated Helmet And Display Sight System (IHADSS), which is basically the monocle imaging system that goes over one eye. For its time, IHADSS was state of the art, but with the right eye looking at imaging that’s presented on the monocle and the left eye looking inside the cockpit or outside, it was something that some pilots struggled with in the past, Jamison said. This is a well-known and challenging aspect of fighting in the Apache that was even made into a plot point in the Apache-centric Nick Cage action movie Firebirds.

Rapid developments in augmented reality and helmet-mounted sights over the past two decades, including the ability to display more information to the pilot, are likely to be key to achieving these improvements.

“It worked really well, for the technology that we had at the time, but now there are new technologies that will allow us to put all of that data on a visor-type environment, kind of like what an F-35 does right now, and so we don’t have just that single piece of an IHADSS. This will make it a much more lethal, seamless capability going forward.”

Other changes in the cockpit are being heralded by the advanced crew station, which includes a large touch screen, instead of the previous multiple multifunctional displays. Boeing is also looking at refining the seating arrangement with the aim of making it more comfortable for missions that might last as long as 10 hours.

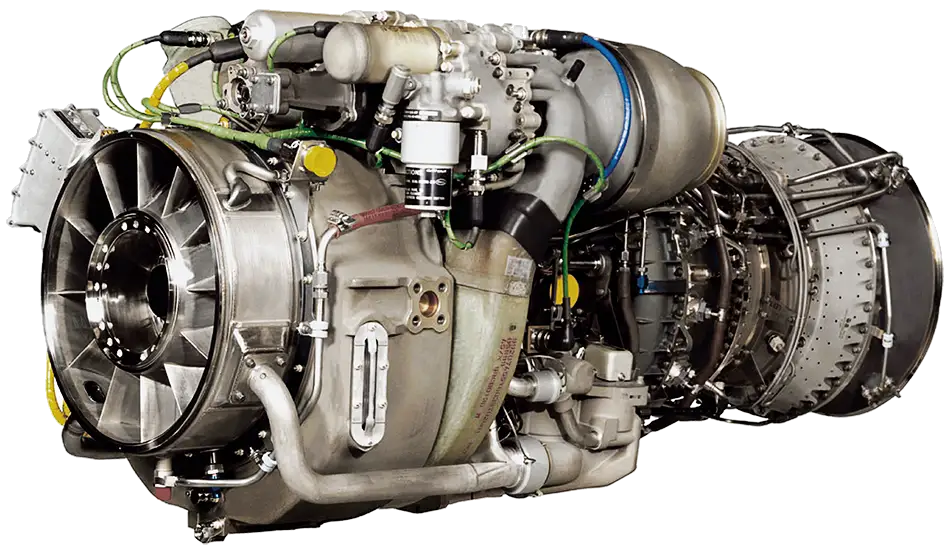

Propulsion systems

The more powerful ITEP engine is very much seen as underpinning the future of the Apache.

“The ability to bring ITEP into the Apache and get a full 3,850 horsepower into that aircraft, that sets you up for room for growth, extended range, reach, and payloads.”

Boeing received a developmental contract for the integration of ITEP into the Apache, but the U.S. Army has, for now, made the decision to prioritize putting the new engine into the Black Hawk.

“There has not been a decision to not put ITEP into the Apache, so we are still working to our customer’s desires and we’re using some of our own funds to continue the design work to get ITEP into the Apache,” Jamison said. “We really firmly believe that you’re going to need that 3,850 horsepower to incorporate some of these additional capabilities.”

Ahead of ITEP, Boeing is working on other improvements to the Apache’s propulsion system, with the Improved Tail Rotor Blade (ITRB) and Improved Tail Rotor Drive System (ITRDS). Boeing is currently under a developmental contract for ITRB, which is primarily focused on sustainment, ensuring the tail rotor blades can be more easily repaired and maintained, including on the battlefield. Meanwhile, ITRDS ensures that more power and authority are delivered to the tail rotor and is seen as something that will pave the way toward ITEP.

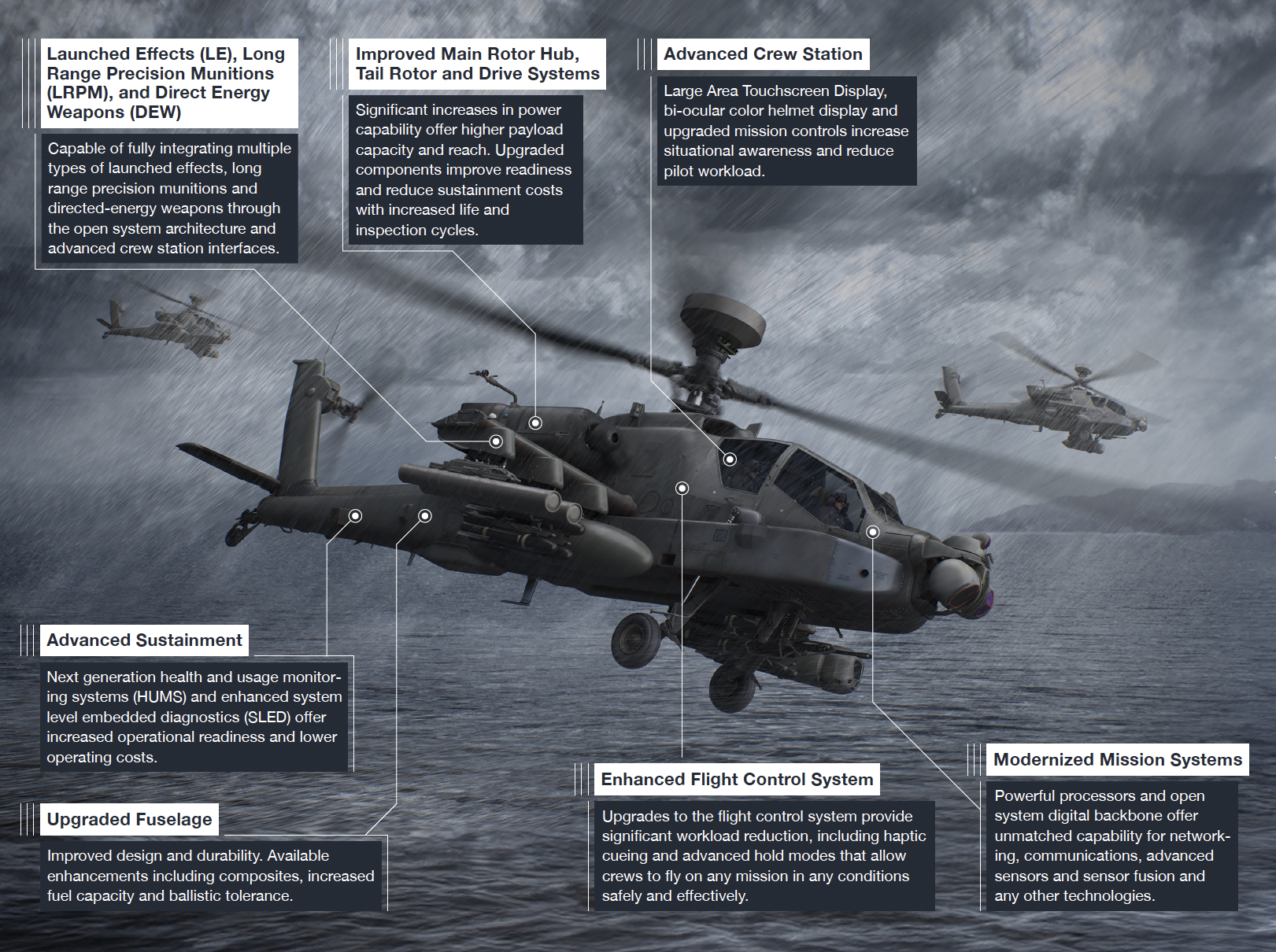

What will the next Apache look like?

Boeing is increasingly focused on what comes after the AH-64E Version 6.5, whatever that might be called. Jamison uses the name Modernized Apache but also references the New-Generation Apache. Importantly, while the next AH-64 might be a new iteration of the Echo, it could be something more radically different.

While its name and final appearance are yet to be determined, this future Apache “is still a very, very active pursuit of ours,” Jamison confirmed.

Boeing is working with the U.S. Army and Futures Command on some of the aforementioned lines of effort that will lead to a Modernized Apache, with some of those efforts — or portions of them — under contract with the Army and some being funded using the company’s dollars.

Boeing sees a need for a Modernized Apache capability in the 2032 to 2035 timeframe and, to achieve that is looking at the option of a remanufacturing program, like that which turns older AH-64Ds into new AH-64E versions.

As Jamison explains, “Our concept, as we go from Echo to Modernized Apache, will be along much the same lines. We believe they will need a new fuselage because fuselages have a lifespan because of the rigors that they go through. We know they will need more power for that growth aspect. So we’re really focused on those lines of effort for that next-generation Apache, whatever it’s going to be called.”

The result should give the U.S. Army not only a zero-time, new-fuselage helicopter but also one that has greater “real estate” onto which new capabilities can be attached.

In many ways, the current vision involves a less dramatic makeover than the kind Boeing had suggested in the past. For example, the articulated tail rotor, which can articulate 90 degrees to provide forward thrust during level flight, “is not in our plans right now,” according to Jamison.

While an articulated tail rotor promised a major boost in performance, Boeing now thinks that cleaning up the fuselage from an aerodynamic perspective and increasing the power through ITEP, will provide the required speeds, although Jamison admits the end result likely won’t be as fast as with an articulated tail rotor. The combination of aerodynamic refinements and uprated engines also promises to increase range and payload.

Retractable landing gear is another performance-enhancing option that Boeing eyed in the past, but it has been dropped for the time being, because the company considers it not worth the effort due to the weight and complexity that it brings.

Jamison did say that Boeing is looking at moving the radar from its mast-mounted position, as a potential aerodynamic improvement, something that doesn’t appear to have been shown in concept artwork so far.

“We’ve got that large piece of flat-plate drag sitting up above the rotor system. At the time we put it up there for a very specific reason, so you could just stick that thing above an obstacle and hide the rest of the aircraft. With some of the new technologies that we have, particularly with Launched Effects and with fully integrated Link 16, it’s allowing us to fight and engage from much greater ranges. Having it above the rotor system is not quite as critical.”

Instead, Boeing wants to integrate the radar into the fuselage, cleaning up a lot of the aerodynamics of the Apache, especially when combined with other aerodynamic modifications. One way of installing a radar internally could be to use a conformal AESA arrays, a technology that is getting ever smaller and more versatile. As Jamison points out, Launched Effects and Link 16 — relying more on third-party sensor platforms and their networked data overall — also reduces the need for any radar in many circumstances, providing another route to gaining targeting data and then prosecuting targets, including at standoff ranges.

Lessons from Ukraine

As to how the war in Ukraine is affecting thinking about the future Apache, Jamison noted the value in understanding how things have evolved in that conflict, but urged caution on jumping to blanket conclusions.

A Russian Mi-35 Hind assault helicopter is brought down by a Ukrainian air defense missile soon after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine:

“There are some great lessons coming out of there,” Jamison said. “And I’m not saying we discount those lessons. We must watch those and pay attention to them, but we’ve got to put them in the proper context. And what I mean by that is you’re looking at two militaries that are not at the same level of sophistication and modernization as NATO’s forces — particularly the Ukrainian side.”

Of the lessons that are coming out of Ukraine, Boeing is “really, really focused on how to counter some of the threats that we’re seeing right now, particularly the counter-UAS capability.” With that in mind, Jamison sees both kinetic and non-kinetic (electronic warfare) counter-UAS solutions as integral to the Apache’s future development path. While these capabilities might not yet be mature, work on bringing open architecture systems to the V6.5 aircraft will ensure that they can accommodate them in the future.

“Think about it, five years ago, was anybody talking about lethal, low-cost drones that are literally flying down Ukrainian or Russian trenches, and chasing individual soldiers? Nobody was thinking about that, so that’s why the open system architecture is so critically important. People will say they know what’s coming next, but have we ever predicted the way a future conflict was actually going to play out? I think everybody’s track record is pretty poor in that regard.”

Apache meets FLRAA

Change of a different kind is also coming to the U.S. Army with the FLRAA tiltrotor, which promises to herald a revolution in air assault operations, with a whole new set of speed, range, and survivability metrics. With that in mind, and with FARA canceled, questions might be asked about how the Apache — or future versions of it — might keep pace with FLRAA’s capabilities and the obvious difference in speed.

When asked about this, Jamison suggested that viewing the Apache as a simple escort to FLRAA — in the mode of a P-51 fighter to a B-17 bomber — is “a very old-school way of thinking that doesn’t really apply to the modern battlefield.”

Instead, the Apache will fight according to its point of impact on the battlefield, the place where it will make a difference, whether that’s in direct support of a brigade combat team on the ground, being utilized as a battalion maneuver element, or conducting deep strike operations into enemy territory.

Aided by Link 16, Launched Effects, and other capabilities, the Apache will exploit its ability to reach deep into the battlefield in support of FLRAA, rather than being a physical presence right next to the fast-flying tiltrotor.

Jamison outlines one scenario in which Apaches are already in the fight, on station, and creating the conditions on the battlefield that will allow FLRAA to quickly ingress or egress. In this way, the attack helicopters ensure that additional capabilities — whether artillery or an anti-tank squad team — can join the fight, by reducing the level of threat against FLRAA as it ingresses in and egresses out.

There remains, however, legitimate questions about how the Apache should be able to reach the areas where it can have an impact, bearing in mind the extended distances at which FLRAA should operate and, once there, whether it would be able to survive in the face of the kinds of advanced air defense systems that a peer adversary can bring to bear. These concerns are only magnified in the Pacific theater, in a potential future conflict with China, where the ‘tyranny of distance’ is compounded by high-end anti-aircraft threats. With the Apache’s combat radius defined as a couple hundred miles or so depending on the loadout and mission profile, its relevance in such a conflict is in question. Using forward arming and refueling points can help with getting Apaches where they need to fight again, but those too can be vulnerable to rapid enemy attack.

While there are a variety of different takeaways from the conflict, the war in Ukraine has certainly raised questions over the future role of the attack helicopter and, amid budgetary constraints, it’s conceivable that the AH-64 fleet — which already consumes a huge portion of the Army budget for rotary aviation — might be vulnerable, if the conclusion is that its previous relevance has been eroded.

Nevertheless, with FARA out of the picture and the U.S. Army aiming to operate Apaches of one kind or another for decades to come, Boeing is understandably confident about the future of the attack helicopter — and that’s before even taking into account international customers. Further sales to Israel and South Korea look increasingly likely and even Canada is assessing a future attack helicopter purchase.

Meanwhile, Boeing continues to refine its now-classic design in a variety of ways. While the latest vision of the Modernized Apache is somewhat less ambitious than previous concepts suggested, it will be fascinating to see what route its development takes next.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com