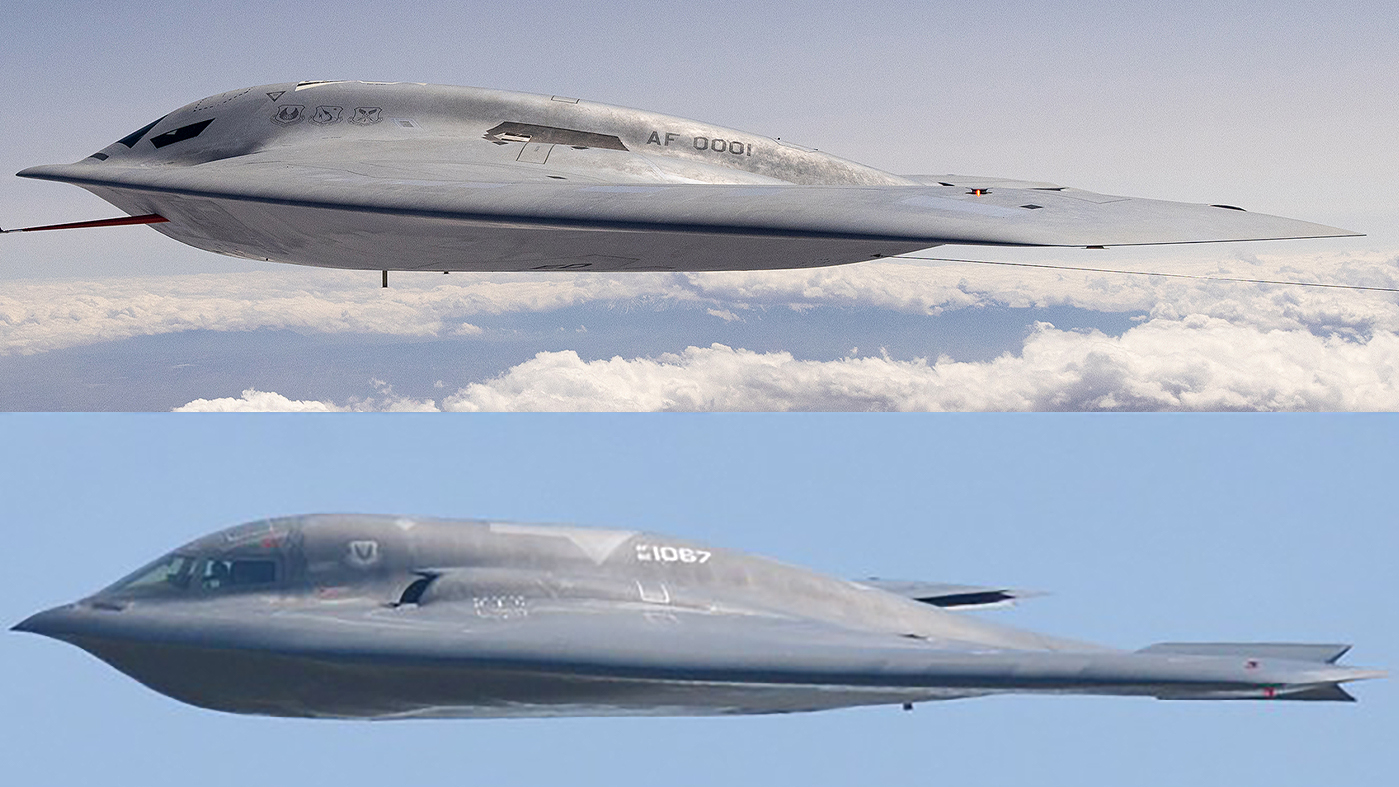

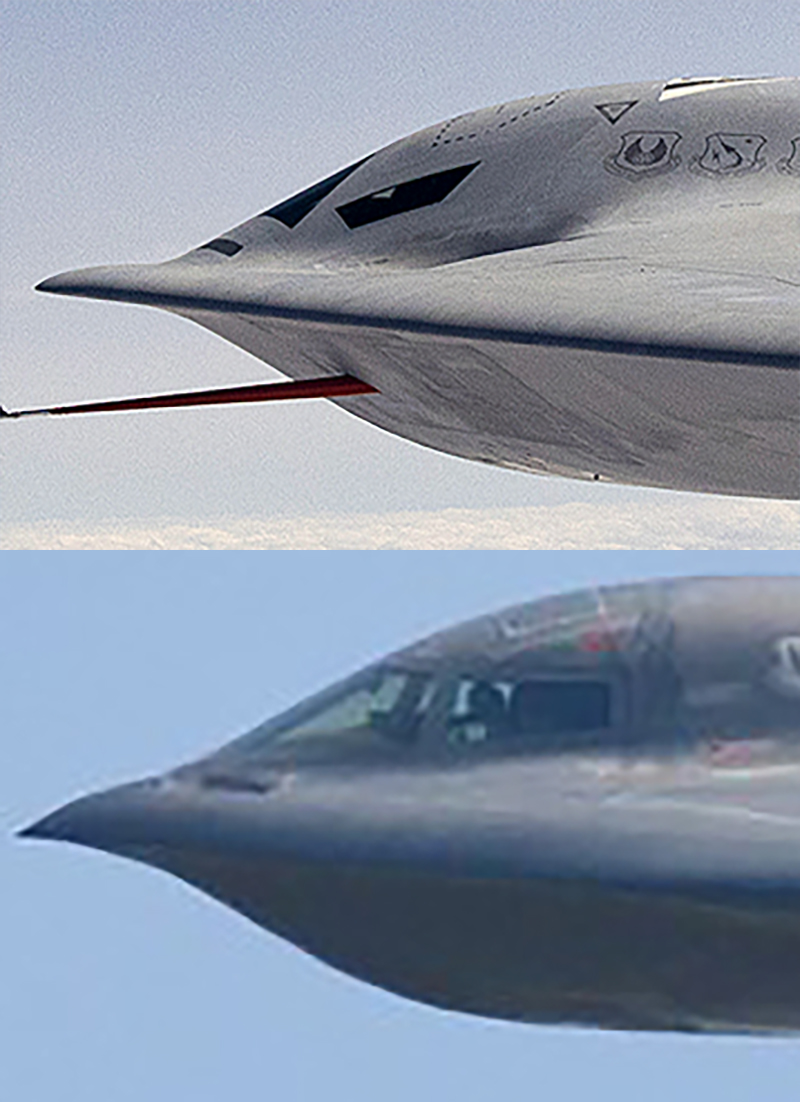

It’s really fascinating to see just how similar, and at the same time how different, the B-2 and B-21 are from one another. Nowhere is the latter more apparent than in each types’ cockpit windows.

The image above, a version of which was posted on X by our friend @thenewarea51, really gives us a great comparison of the two aircraft from a similar angle and under similar lighting conditions. The scale is not exact as we still don’t know the dimensions of the B-21, but it is overall a smaller aircraft than the B-2. You can read our complete analysis of the first aerial image of the B-21, as depicted in the comparison image, here.

The B-21’s bizarre window arrangement puzzled the public when it was first unveiled in concept art posted by the Air Force in July of 2021. As you can see in the latest side-on images, the B-21’s cockpit glazing is a total departure from the B-2’s wraparound windscreen. The side visibility through the B-21’s angled slit windows, which were clearly a heavy compromise between functionality and low-observability (stealth), especially from critical frontal, lower aspects, is arguably not what’s most striking here. The forward viability is. The windscreen appears to offer a relatively narrow forward field of view, confined to directly ahead of the aircraft, and there has been a premium put on the vertical, not horizontal field of view. As we have stated since the B-21’s rollout, this is likely to facilitate aerial refueling, which is an absolutely critical capability for the extremely long-range B-21. The limited window apertures truncating the view outside are also compounded by the fact that a dashboard will extend back quite a ways under the raked windscreens to where the pilots are actually seated.

Also keep in mind, as noted earlier, that the B-21 is physically smaller than the B-2, with its cockpit looking tight in comparison, so these windows are likely even smaller than they seem. The alien design of the B-21 also makes judging scale very challenging. If you look at the ejection seat apertures above the flight deck areas on both aircraft, the size of the B-21’s windows become more apparent. Also, remember the B-21 is likely about the length of an F-15 — the B-2 is roughly 69 feet long by comparison, just over five feet longer than an F-15. So the cockpit windows in comparison to the jet’s total length, and compared to the size of the humans that will inhabit the jet, are a bit easier to decipher, and they look even smaller when taking that information into account.

Even giving the B-2 a full set of cockpit windows nearly 40 years ago when it was being designed was debated. Part of the argument against doing so was that the crew would have needed to be closed off from the outside world during nuclear delivery operations — its core mission — due to the blinding flash of nuclear detonations. The B-2 ended up getting its wraparound windscreen and a frame that can accommodate a flat panel of instantly tintable glass. This system would be installed on nuclear missions, leaving the dash of the B-2 open during conventional operations. You can often see the inner frame for this system in cockpit images of the B-2.

The need for pilots to see outside is becoming less of a necessity as technology moves forward. Enhanced vision systems, computer-generated terrain avoidance and synthetic vision display capabilities, and in-cockpit augmented reality mean that there are very real and relevant workarounds to looking out the window for advanced aircraft. A distributed aperture system could allow B-21 crews to ‘see through’ the aircraft from any angle and in infrared wavelengths while wearing helmet-mounted displays, for instance. The extreme awareness provided by the B-21’s advanced sensor suite could also provide an extra margin of safety even when traveling in densely populated airspace. On the other hand, NASA’s X-59 QueSTT supersonic demonstrator has no forward visibility at all. Automation and rapid leaps in autonomous piloting are also changing this equation. It’s worth noting that the B-21 is still slated to be optionally manned. To what degree the USAF plans on using this capability remains unknown.

We also don’t know what creature comforts were built into the B-21 from the start considering all that’s been learned about human needs for flying global airpower missions that can last well over a day. For instance, an area on the B-2 that was originally intended for a third crew member has been repurposed with a small improvised cot so that one of the two pilots can rest during the long transits. A small toilet also exists on the Spirit so the crew can relieve themselves more easily than using ‘piddle packs.’ One would imagine Northrop Grumman would have made the B-21 a bit more accommodating for these super long-range operations from the get-go, but we really don’t know what these features could include, although we have asked.

The B-21 is Northrop Grumman’s second shot at a flying wing stealth bomber and a far more mature evolution of the B-2, with decades of experience building, operating, and sustaining it factored in. Even the Raider’s planform is taken directly from what the B-2 was supposed to be, before the USAF introduced low-level penetration requirements to the Advanced Technology Bomber program. The subsequent Spirits were absolutely ‘bleeding edge’ in nearly every regard when they were built. One could even consider the B-2 as an experimental production aircraft of sorts, with just 21 being constructed. And while the original stealth bomber shares many traits with its successor, they are still significantly different, both in terms of key elements of design and in planned mission sets. You can read all about this in our past deep dive on the topic here.

But the choice of cockpit glazing underscores the premium put on low-observability and the Raider’s ensured survival for years to come. At the same time, it could also be indicative of other technologies being integrated into the bomber that make flying with reduced visibility a largely mitigated issue.

Contact the author: Tyler@twz.com