Air-launched ballistic missiles, which are experiencing a renaissance in many parts of the world, offer significant benefits for carrying out stand-off strikes, especially against highly-defended, time-sensitive, and hardened targets. For the U.S. military, huge potential appears to exists in adapting the U.S. Army’s new Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) short-range ballistic missile for air-launch applications. Doing so could offer a relatively quick path to acquiring the capabilities that weapons like this provide — ones that are missing from the U.S. arsenal — at a time when the need for them is becoming increasingly critical.

Israel Aerospace Industries’ (IAI) official unveiling of an air-launched version of its LORA (Long Range Artillery) short-range ballistic missile, or Air LORA, has underscored the growing interest globally in air-launched ballistic missile capability. Israeli firms alone are now offering two kinds of ballistic missiles that aircraft can fire, the other being Rafael’s Rocks, which is derived from the Sparrow line of ballistic test targets. The is also Israel Military Industries’ (IMI) Rampage, an air-launched adaptation of a long-range guided artillery rocket design that also flies to its target along a ballistic trajectory. Israel looks to have employed air-launched ballistic missiles in retaliatory strikes on Iran in April.

Outside of Israel, Russia has its Kinzhal air-launched version of the Iskander-M short-range ballistic missile. This is the weapon that really kicked off the current surge of interest in air-launched ballistic missiles back in 2018 and it has been actively used in combat in Ukraine. China has also now been working to field multiple tiers of air-launched ballistic missiles, including derivatives of the DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile and short-range types more in line with Air LORA and Kinzhal. It is important to note that the idea of an air-launched ballistic missile is not new and multiple armed forces, including the United States, have eyed such weapons on and off again since the 1960s.

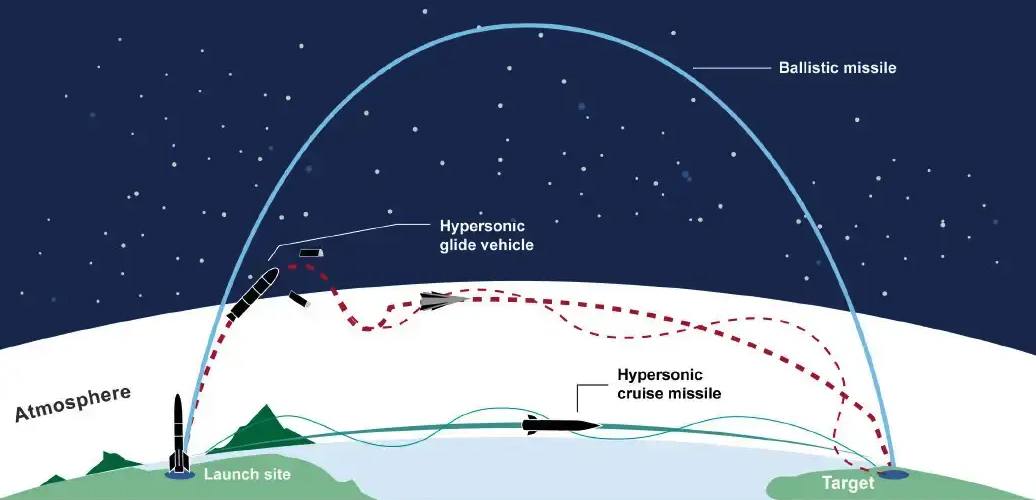

The U.S. military is not presently developing an air-launched ballistic missile, at least that we know about. The U.S. Air Force had been pursuing an air-launched hypersonic boost-glide weapon, the AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW), to address its need for a prompt long-range, air-launched, conventional stand-off strike capability. However, the future of that missile, or a follow-on design, is now unclear. Though they might look similar externally, ARRW and other weapons like it are completely different from traditional ballistic missiles, as we will come back to later.

This is where the PrSM short-range ballistic missile could come into the picture. The U.S. Army received its first operational PrSMs, which are currently designed to be ground-launched from M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) and M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) vehicles, late last year. The service hopes to reach initial operational capability with the weapon sometime this year. The missile has a range of at least 310 miles (500 kilometers), which could grow to 400 miles (650 kilometers) in the future.

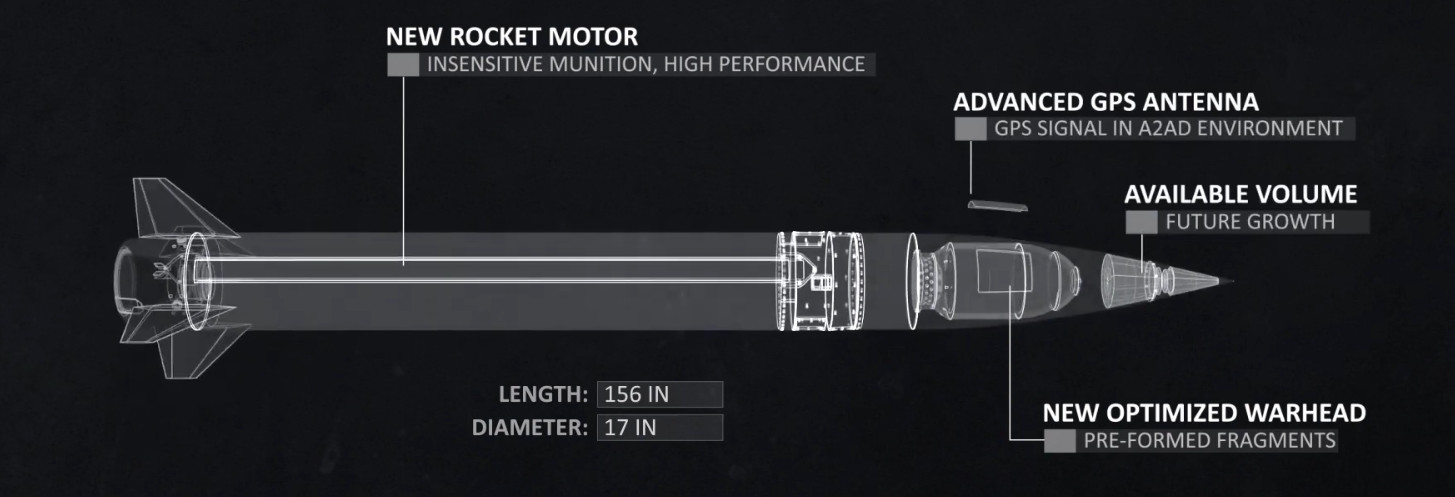

PrSM’s manufacturer, Lockheed Martin, has said in the past that the baseline version is 156 inches (13 feet or nearly four meters) long and 17 (just under one and a half feet and close to half a meter) inches wide. It is unclear how much the missile weighs, but a standard “pod” loaded with two of these weapons has a gross weight of approximately 4,615 pounds, according to the Army. This would seem to put PrSM very roughly in the 2,300-pound weight class.

As a point of comparison, PrSM’s external dimensions are smaller than that of LORA (17 feet or 5.2 meters long and two feet or 624 millimeters in diameter), which also weighs some 3,527 pounds (1,600 kilograms), according to IAI. Air LORA is assumed to be similar, if not identical in general size to its ground-launched counterpart. IAI has at least test-launched Air LORA from Israeli Air Force F-16Is, showing it can be employed by medium-weight tactical jets. The company is already pitching the weapon as a potential addition to the arsenals of other aircraft types, including current-generation variants of the F-15 combat jet and the P-8 maritime patrol plane, as can be seen in the video below.

There is a strong precedent for turning ground-based short-range ballistic missiles into air-launched types, even in the United States. The U.S. Army’s current Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) short-range ballistic missiles, which are larger than the PrSMs now set to replace them, evolved from a joint program that included plans for an air-launched companion. You can read more about the Joint Tactical Missile System (JTACMS) program here.

ATACMS has become something of a household name around the world thanks to the U.S. military transferring stocks of them to Ukraine’s armed forces. Ukrainian units have demonstrated the glaring effectiveness of these weapons, especially against some of Russia’s most modern air defenses, including S-400 surface-to-air missile systems, and aircraft parked out in the open at air bases. Ships, troop concentrations, and other targets have also fallen victim to ATACMs.

So, an air-launched version of PrSM capable of being employed by tactical combat jets like the F-15 and F-16, as well as larger platforms like the B-52, the forthcoming B-21, and the P-8, could be an immense boon to the U.S. military. PrSM’s smaller form factor compared to weapons like Air LORA could make it easier to integrate onto fighter-sized aircraft (and be less taxing on them to carry), as well as expand the total number that bombers might be able to lug around, including in their internal bays.

Ballistic missiles, in general, reach high-supersonic, if not hypersonic speeds (above Mach 5) in the terminal phase of flight. That speed increases the capacity of these weapons to burrow down into hardened targets and also reduces their overall flight time, making them particularly well-suited to striking hardened and/or time-sensitive threats. Fast-flying ballistic missiles are also very challenging to intercept and otherwise give opponents limited time to react in any way.

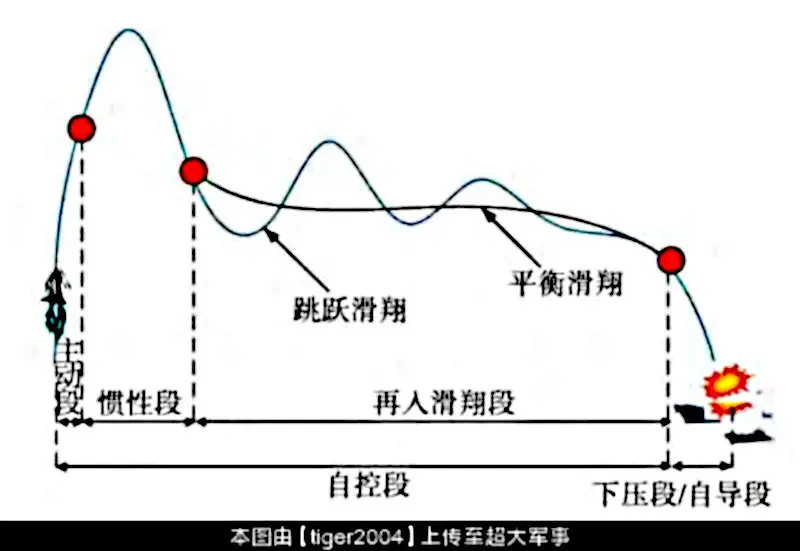

Many modern ballistic missiles also have some ability to maneuver during portions of their flight, which can be used to help reduce the chance of interception. The ability to follow a so-called “porpoise” or “skip-glide” trajectory, which involves the missile abruptly pulling up at least once, but potentially multiple times, which then creates an equal number of downward “steps,” is a prime example of this kind of capability.

To reiterate, ballistic missiles with maneuvering capabilities are entirely distinct from novel hypersonic weapons using unpowered boost-glide vehicles, the latter of which have higher degrees of maneuverability at higher speeds. Hypersonic boost-glide vehicle weapons can also fly farther over relatively flat non-ballistic trajectories and move erratically during their flight, as you can read more about here.

Air-launched ballistic missiles offer additional flexibility, especially over ground-based types, by expanding the number of potential launch points and vectors. This, in turn, presents additional complications for defenders and opportunities for the shooters.

Any missile fired from an aircraft also benefits greatly from its launch platform’s speed and altitude, especially in terms of range and end-game kinematic performance. So, launching a ballistic missile at a high altitude and speed would give it significantly greater reach than it would have when employed in a ground or sea-based configuration. Kinzhal, for instance, benefitted dramatically in terms of range extension by being air-launched.

For the U.S. military, the need for more long-range and survivable stand-off strike options is only set to grow as near-peer competitors like China and Russia, as well as smaller nations like North Korea and Iran, continue to field more robust air defense capabilities. China, in particular, has been investing heavily in a broader anti-access and area denial strategy across broad swaths of the Western Pacific designed to limit the overall freedom of movement of hostile forces in the air and down below in a future major conflict.

Leveraging PrSM, specifically, to create a new air-launched ballistic missile could provide a ready path to additional future capabilities. The baseline version of the missile, also known as Increment 1, is designed to strike fixed target coordinates, but the Army is already working on an Increment 2 version with an additional seeker system primarily for use against ships, even ones on the move. The services hopes to be able to start fielding Increment 2 PrSMs as soon as 2026.

There are two more spiral PrSM developments, Increment 3 and Increment 4, already in the works. Increment 3 is centered on unspecified “enhanced” payloads over the unitary high-explosive warhead found in the baseline version. This might include the ability to unleash swarms of loitering munitions, also known as kamikaze drones. Increment 4 aims to increase the missile’s maximum range to 620 miles (1,000 kilometers). Increment 4 may turn out to be a substantially different design that includes the addition of an air-breathing propulsion system, but that could also be adapted for use in an air-launched mode.

Giving an air-launched PrSM multimode seeker capabilities, potentially including radar and anti-radiation abilities, would make it an even more formidable destruction of enemy air defenses (DEAD) weapon than it already is. This would allow it to hit fleeting targets even after they stop radiating at greater distances than even the upcoming Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile – Extended Range (AARGM-ER) missile.

An air-launched PrSM could present massive cost benefits, as well, especially when compared to novel hypersonic weapons. In the past, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that a weapon like ARRW could have a unit cost of between $15 and $18 million. The Army’s 2025 Fiscal Year budget proposal puts the Increment 1 PrSM’s unit price at just under $1.5 million. PrSM production is starting to ramp up, and a USAF buy could help push those unit costs down further. Such an expanded buy would also result in more robust supply chains for the weapon in general.

Though not nearly as capable or long-ranged as a hypersonic boost-glide vehicle weapon like ARRW, an air-launched PrSM would still have significant reach and survivability, and could be acquired in larger numbers at a far lower relative cost. This, in turn, would help allow weapons like ARRW to be kept in reserve for use against extremely heavily defended and high-value targets like major air defense and other command and control nodes, especially during the open stages of a conflict.

As already noted, demand for the kind of stand-off aerial strike capability that an air-launched ballistic missile offers, including within the U.S. military, is only likely to grow in the coming years. Other countries, including the United States’ chief competitor China, are clearly taking notice of this reality.

Altogether, PrSM looks to offer a very attractive set of features that are already efficiently packed into as close to an ‘off-the-shelf’ weapon system as possible that could drastically expand America’s air-launched strike options. Considering what an ‘Air PrSM’ based on the already in-production missile could bring to the table, and the growing international precedent for these weapons, one has to wonder why this concept isn’t already being aggressively perused.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com